Joshua White: The States Project: North Carolina

I can see a big warm smile and a quickly waving hand accompanying a jolly “Hey buddy!” when I look at the images from Joshua White’s New River project. This is how Josh greets me when we see each other; sometimes even over the phone I find myself instinctively waving eagerly into the space around me as if he could see my enthusiasm. I see New River as a visual record of Josh becoming familiar with his new home. North Carolina is curious place. It feels so familiar and so foreign at the same time. There is a rich history of photographing in the Appalachians, the rural south, and the poverty that pervades these geographies. New River feels different to me. The images reflect a familiarity, comfort, and discovery that are part of making a place a home. Josh guides us through navigating the river region pausing on moments that a stranger may miss. The typical homogenous scenes are avoided: coalmining towns and mountain shacks; barefoot and dirty kids playing outside in their tattered clothes; the weird white guy playing a banjo. When I mentioned that last one during a conversation with Josh, he exclaimed, “I’m that guy!” There is actually some truth to this. Josh has invested time and heart into being part of his community and making North Carolina home for he and his family. He taught himself to play banjo and received 5th place in an old time banjo competition this summer. In late September we had a Society for Photographic Education Southeast Chapter retreat at Penland, not far from the New River. At the close of Saturday’s activities, they had a bonfire and s’mores. Josh brought his banjo and began playing once the feeling around the fire was right. This balance between keen awareness of place/space and intuition come together as he crafts images of community, land, and his own experiences in them.

New River shows us the beauty and authenticity of a place. Its not just a description of geography, but an insight to the people, the community, the little details that words and pictures often fail to capture but on occasion can trigger the memory of something familiar and yet still new.

Joshua White uses photography and mixed media to investigate memory, mortality, and ecology. His work has been shown internationally, and his work has been featured by National Geographic, Don’t Take Pictures, Wired, Gizmodo, and Feature Shoot, among others. He received his MFA in Photography from Arizona State University, and is the Photography Area Coordinator in Studio Art at Appalachian State University in Boone, NC.

New River

When I moved to North Carolina, I was told that the New River is the oldest river in the world. Growing up on the Ohio River, and having always been drawn to the water of a place, I was immediately intrigued and began researching the topic. It turns out that the New is not, in fact, the oldest river in the world, but numbers among the oldest rivers along with the Finke River in Australia, the Yangtze in China, and the Meuse River in France. In any event, just the notion that the river was so ancient, older even than the Appalachian Mountains, was enough to get me started on this project. I started to think about personal histories, and how a river affects economy and the communities through which it flows, but also about Pangea, and where North Carolina used to fit against Africa, creation stories and the Garden of Eden, and how religion is a large part of this region and my past. I love the fact that the same water that starts in a seep high up on Snake Mountain in Meat Camp, North Carolina, not far from my home, flows north to confluence with the Kanawha River outside Charleston, WV, and later joins the Ohio River that flowed past my hometown in Indiana. I would sit on those banks for hours, just watching the water slip past, and now it is like I have traveled back in time, away from my home but closer to my origin.

We both acknowledge that the relationship between photography and the Appalachians, the South, rural areas, poverty…this is a tenuous being. Your images consciously work against this traditional structure of document or record of the place. Can you talk about the feelings, process and/or internal dialogue you have to prevent entering the homogeneous zone?

I think what you said during our conversation, that I am trying to make myself an insider, is a huge part of it. I think that a lot of people are doing a lot of great work, but there is a kind of aesthetic that a lot of Southern photography has. I don’t know that I am conscious of that when I am shooting, but it is like you said, that I am photographing this place as a way of understanding it, a kind of courtship dance I am engaged in to understand my new home. I don’t want to photograph this place as a means of looking at what it means to be Southern, or Appalachian, or any specific category. I am interested in the things I find and learn, and find that the results are so much more nuanced than I could plan or reduce with some kind of specific parameters, especially right now. I have been photographing on the project for around 3 years, and I feel like I am just scratching the surface. I don’t have an agenda, or a plan, just the desire to learn more about this land, this river, and the people I am growing to know and love.

Finding threads through one’s creative endeavors, through life, and with others is an activity that I know you enjoy and, I believe, also actively pursue. Do you think that the connection is created by the art making or that the art making comes from connection? Or maybe its something different…either way, I’d love your thoughts on it!

I think it is a little of both. My practice usually starts with very small, simple ideas. I want to know more about a topic that has intrigued me, and I begin to investigate visually. I often worry at first that bodies of work might not be connected, but that feeling has grown weaker over time. I have begun to trust the process, and understand that while those connections almost certainly won’t be apparent to me at the beginning, the work is coming from the same well, from the same general kind of curiosity I had as a child, just wondering how things work, and how I fit into those machinations. That’s why I am still so open to the direction of this body of work: it is still in the process of becoming, the balance of control and chance is delicate, and I want to try to hold those sometimes competing forces in equilibrium so as not to spoil the sanguine prospect of discovery.

How does teaching influence your creative process? Feel free to be candid!

I decided early in my undergraduate education that I wanted to teach. I was changed by my professors, and want to try to help my students in that same way. One of the things I love most about teaching is that it forces me to constantly reexamine my relationship to photography and how it functions in society. I will often say things in critiques or portfolio reviews that I haven’t realized about my own work, and am able to revisit images I have created with a fresh eye. I rarely teach my courses the same way twice, and this forces me to continually mine the depths of the medium, finding new connections, discovering artists I have forgotten or never knew, and looking for ways to incorporate other forms of knowledge and investigation into my teaching. My curiosity touches all aspects of my life, and teaching keeps me actively searching, both out of desire and necessity.

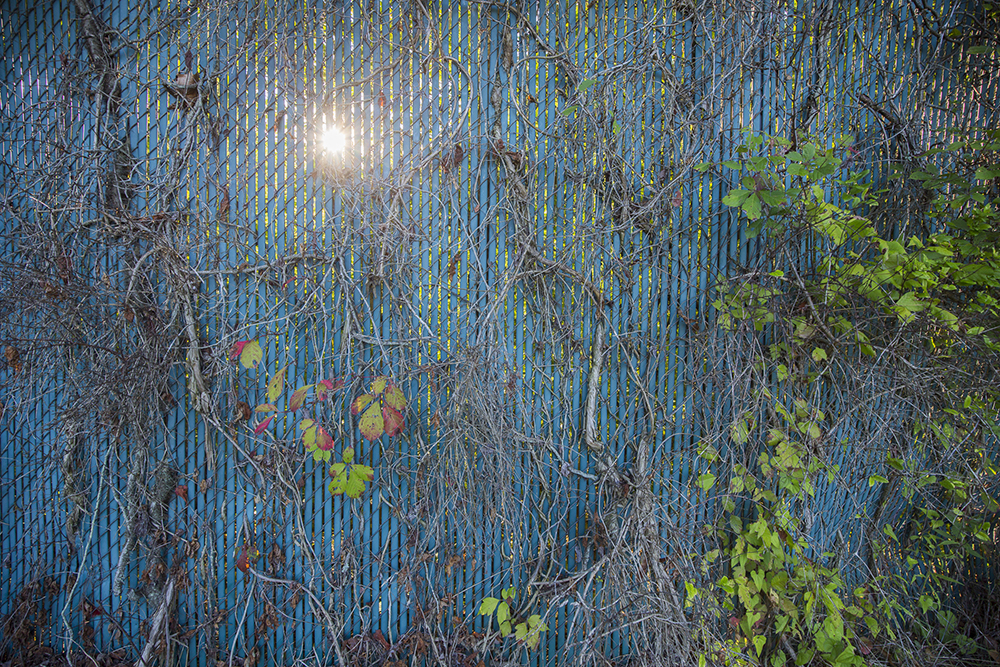

This is the first pool that forms at one of the headwater seeps of the New River. The source, just before the small streams trickle down the mountain and join up to form the North Fork of the river. I wondered what a seep was, and after a few unsuccessful hikes I finally found out. As I walked through this foggy field, my feet began to sink into the mud, and I realized I was walking in water that was coming out of the mountain, but not out of a spring, just up from the ground.

Teashia, photographed near the confluence of the North and South forks of the New River, at Twin Rivers Campground in Crumpler, NC. I came to photograph the confluence, and met the owner, Susan Carter, and we talked about photograph, the history of the camp, and the river. She invited me back to photograph a gathering of the High Country Bus Festival, a group of VW Microbus lovers who use the camp for an annual gathering. It was a wonderful experience to be welcomed into such a wonderful community, and I photographed along with my assistant for several days, bringing back prints and sharing stories with the club members.

Sue’s family has owned land on the New since the Revolutionary War. She is a strong supporter of the New River Conservancy, and advocacy group that works to protect and maintain the river.

Hydroelectric dam at Fries, VA. These stalactites have formed from the minerals in the water that leaks down the sides of the building adjacent to the dam. As I was photographing them, the groundskeeper who had been mowing came to tell me I couldn’t photograph where I was standing. I turned to leave and he said, “You can photograph there.” Pointing to a spot three feet behind where I had been standing. The cascading colors and texture reminded me of geologic time, and how the river predates the Appalachian Mountains, some of the oldest mountains in the world.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography & Anthropology: Raquel Bravo Iglesias, “Mato Grosso”May 1st, 2024

-

Earth Week: Ian van Coller: Naturalists of the Long NowApril 22nd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Shari Yantra Marcacci: All My Heart is in EclipseApril 14th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024