Ashlae Shepler: The States Project: Colorado

Collaboration is a key element to Ashlae Shepler’s practice. The series Lest We Travel Too Far, made with long term collaborator Leah Gose, documents commonplace scenery and our connection to the landscape as observed in their travels through the United States. Using lenticular film cameras and displayed in grids, the work combines the surrealist strategy of a photographic Exquisite Corpse with the mid-century aesthetic of street photographers like Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand. I interviewed Ashlae about her creative work and how she expands the idea of collaboration.

Ashlae Shepler is a freelance writer and photographer in Denver, Colorado who likes to explore historical techniques in photography and visual storytelling. Her fine art photography work has been exhibited in galleries and museums nationally, and she teaches workshops for Denver’s various local organizations. The collaborative team, AS + LG CoLab came together during Ashlae and Leah Gose’s graduate studies at Texas Woman’s University, where together they explored themes like voyeurism, optical illusions, and human psychology. The work continues to explore the role photographs play in perception, memory and our sense of self.

Lest we travel too far

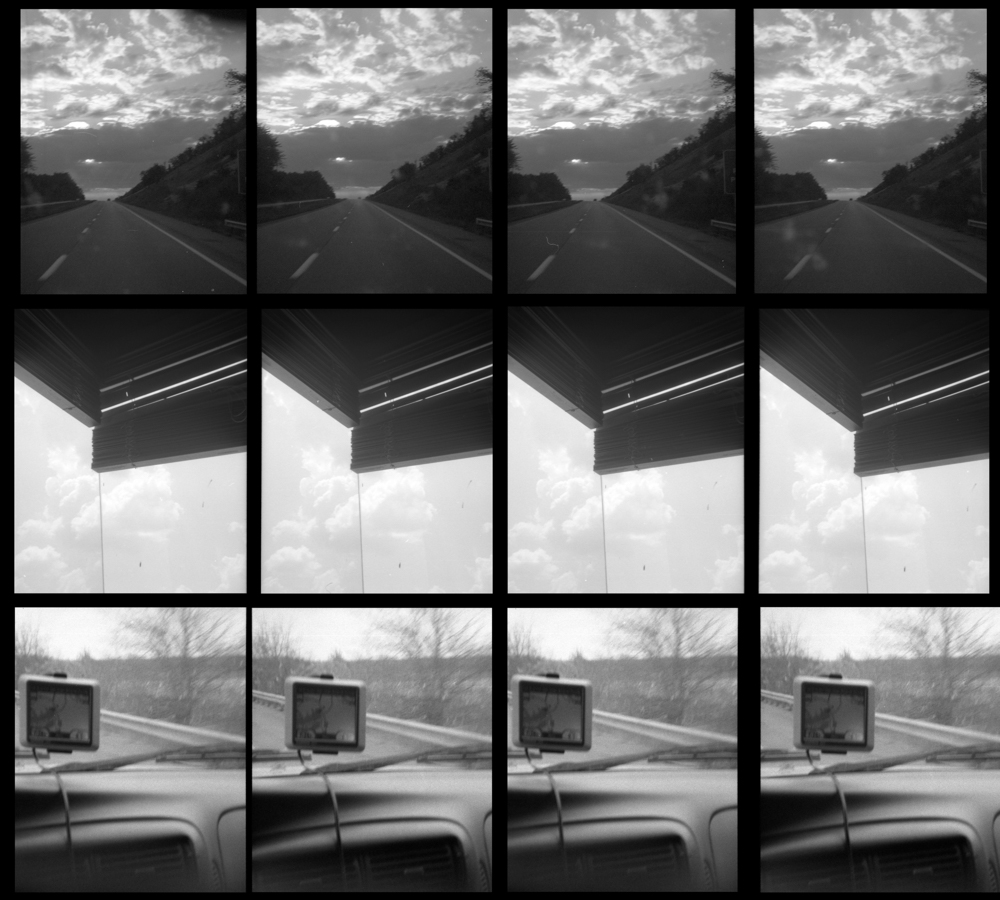

We have the privilege to roam across the American landscape time and time again, as far as our dollars and our cars can take us. Many Americans take this freedom for granted, enjoying a transient lifestyle where the places we spend our time shapes our sense of adventure and self-discovery.

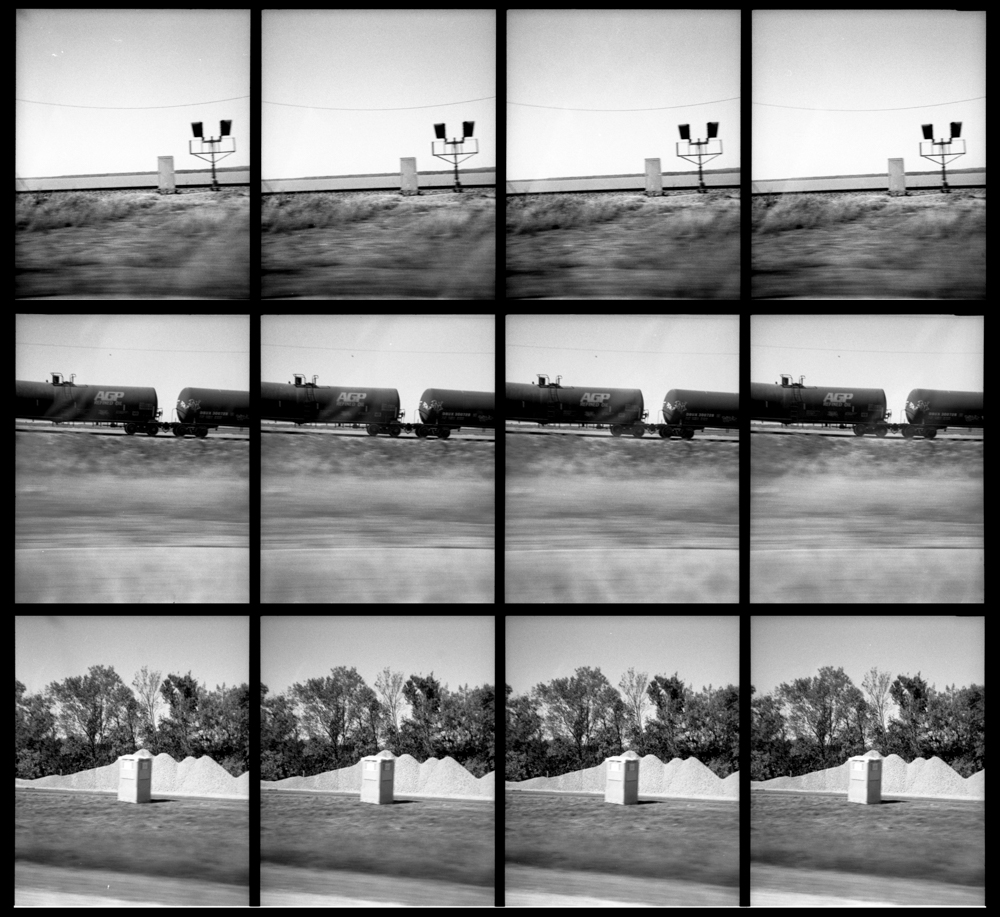

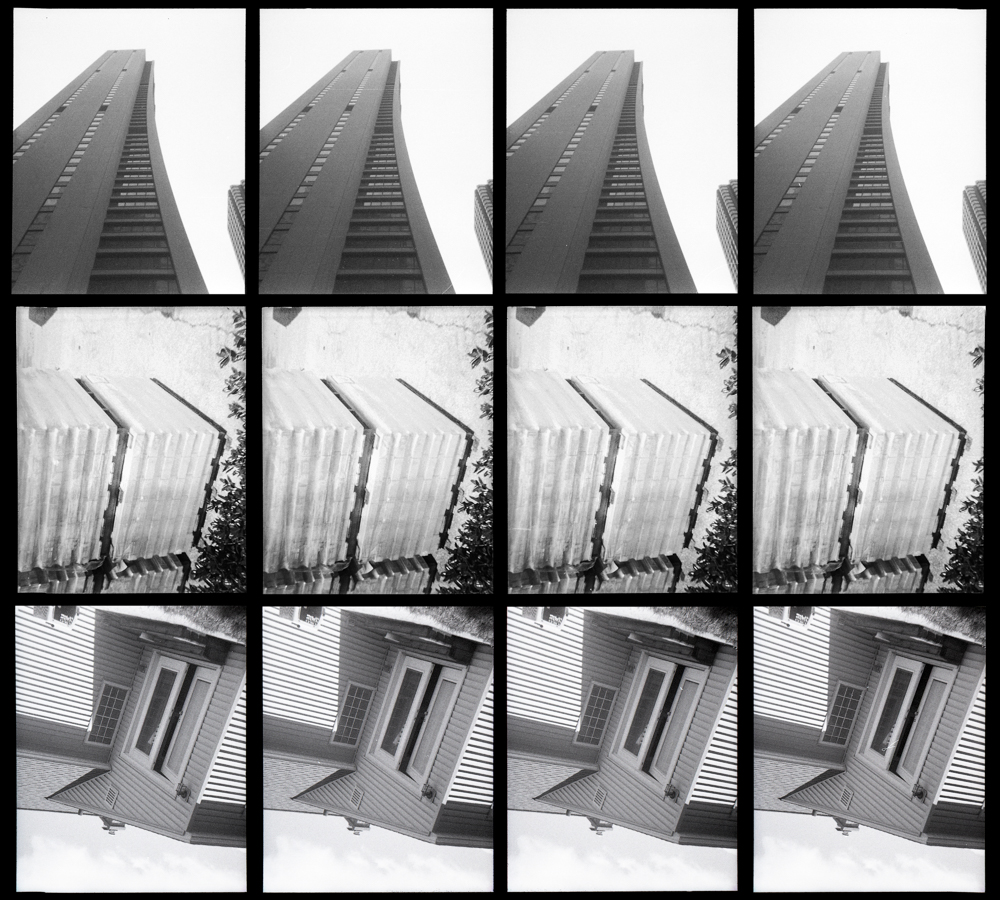

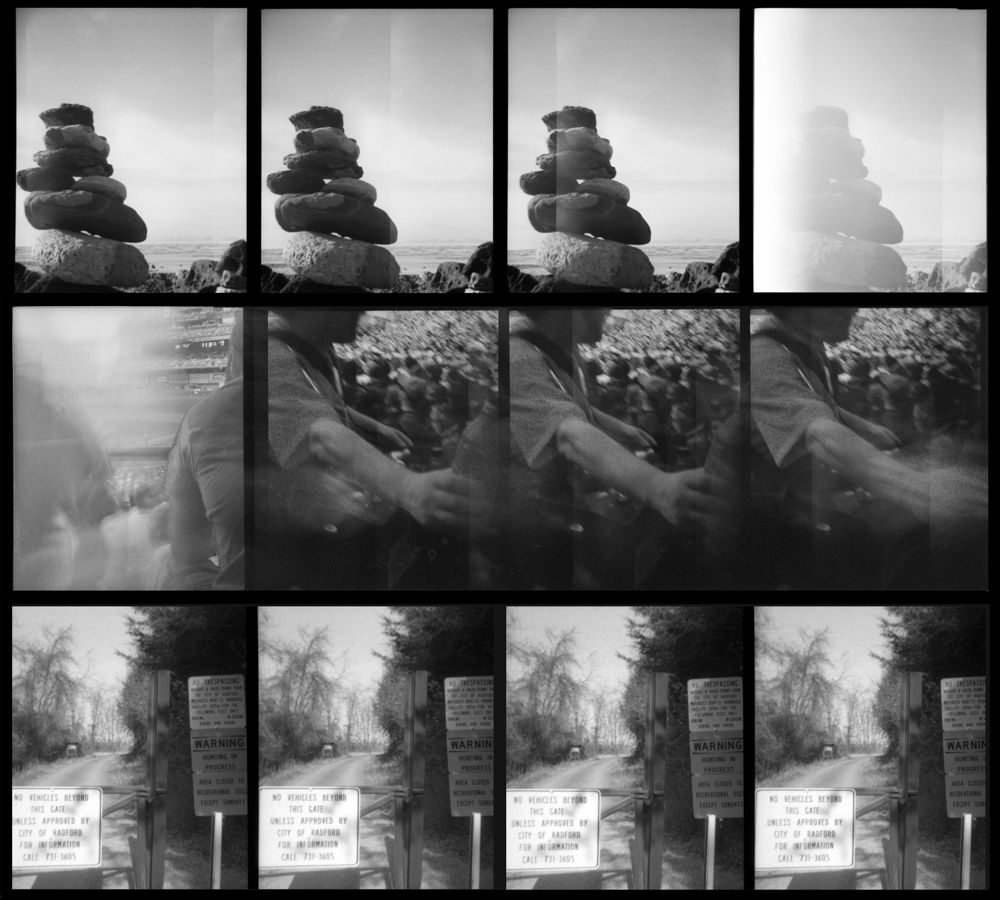

Through a collaborative partnership with Leah Gose, Lest we travel too far illustrates our travels using 4-lens lenticular film cameras, making images similar in approach to Jack Kerouac’s meandering On the Road, post-war American idealism, and street photography. With this approach, we build a library of photographs that we trade and re- construct into various prints, videos and photographic sculptures, using the grid-like frames to impose a structure around the narratives we build.

The cheap, plastic construction of our cameras creates romantic, soft-focus exposures, but it also causes a number of light leaks and miscalculations that signify our attempts to capture and keep memories. The multiple frames begin to feel like snippets from cinema reels that we then use like syllables in a poem.

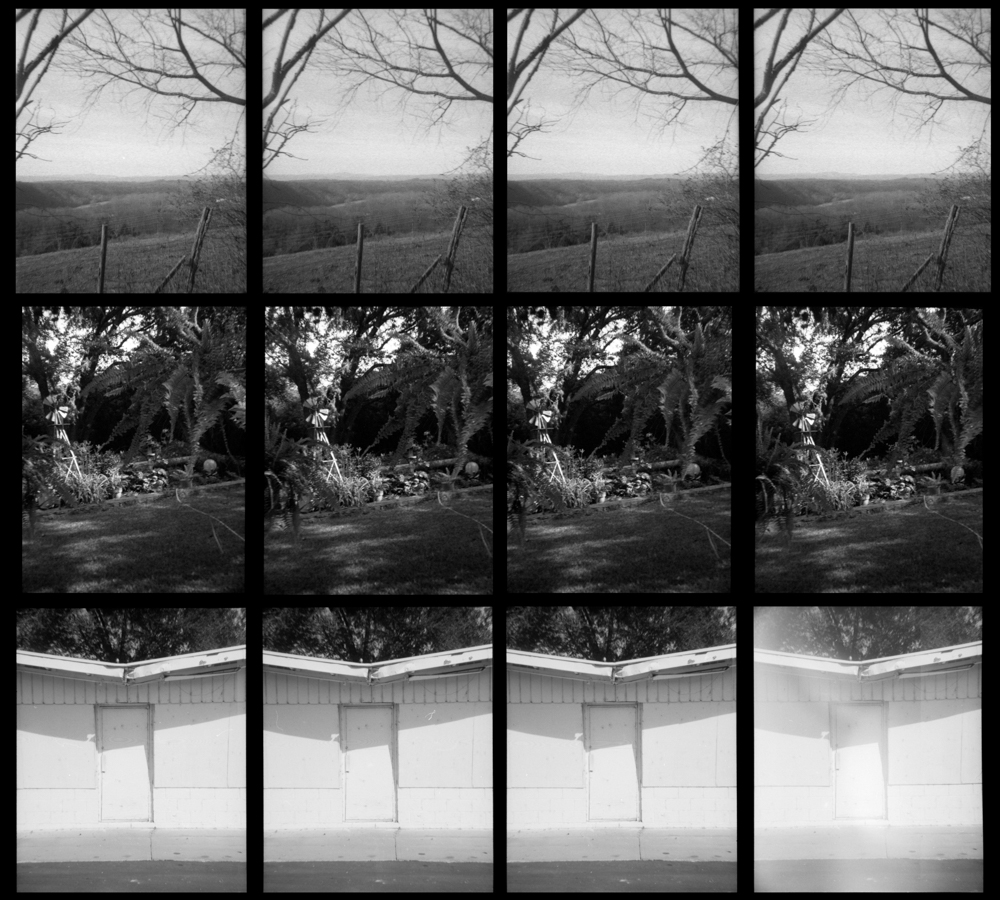

Over time, as the places we’ve visited and our relationships with them change, our objects explore this sense of impermanence. Some images seem timeless, while others leave clues to dates and trends. As these landscapes change over time, the photographs become powerful reminders of immense loss or great gains.

As our work continues, we begin to observe the cycles of abundance and scarcity and begin to realize the advantages our privilege brings, and what we stand to lose when the rules suddenly change and these places are no longer available to us.

You and Leah live in different parts of the country. How did your collaboration start and how does it endure?

My work and her work converge in a really interesting crossroad of perception, psychology, memory, and emotion. We wanted to continue to work together on these similar concepts after grad school. We seek ways to relate to the landscape but also create a psychological attachment to it and how that creates meaning to our experiences. It was an individual endeavor that we then share with each other. We are looking for things influenced by street photography, Jack Kerouac’s On The Road, that sort of post-war idealism of American Landscape, the road trip, where we are going. It is rooted in seeking ourselves but also seeking a common experience with each other and other people we don’t know.

In what ways do your exploration of landscape converge? What are similarities and differences that you experience?

A strong similarity between the two of us is that we are really drawn to separating ourselves from people. It is not isolation or loneliness, but is alone-ness that we both seek. We use photographs to observe, to record, and to help us let go. Over the course of the work, each of us has moved to different places. It helps us process the emotions associated with change. The absence of people in the photographs allows them to be ambiguous, timeless.

The way Leah approaches making photographs has influenced mine. Leah focuses more on the formal qualities, the shape, tonal qualities, composition, and using the camera the way it does with four frames next to each other, she started thinking about how the images move left to right sooner than I did. Once she started experimenting with that, I became more aware of it. The next challenge was the way we assemble the three rows to move from top to bottom. That is the evolution. I started to question… these images alone are pretty, but are they meaningful? Are they meaningful to other people? How can others relate to images that come from our uniquely personal experiences? I’ve been able to stretch that human component in our work.

The linear structure of the images is defined by your camera choice. How did you choose that camera?

We discovered the plastic camera with four lenses in a dollar store. Inside, there were instructions that you send the film off and they’ll send back a 3D picture. We loved the soft focus and the really interesting tonal range it would get with the type of film we were shooting. Because of the aesthetic quality it produced, a really strong sense of sentimentality, romanticism; more dream-like than it is stark, contrasty or sharp. It made sense to pair with it our view of seeking some meaning in our new locations and be able to relate to that. We stuck with it because of the language created by the camera.

Putting together three rows gave us a challenge to start. It was our place to start. I suppose the number 3 was a subconscious connection with the “3D” feature the camera was designed to do, but it was also a challenge to see where we could take our storytelling with these snippets of images. And because they are so similar to cinema clips, we also developed animated films in Photoshop from the individual frames. The animation really exaggerates the camera’s parallax shift, and it works with the concepts we’re developing in this body of work. We couldn’t resist the endless combinations we could make using the negatives.

We’re now moving in a more 3-dimensional direction with box structures and installations since the camera originally was meant to create 3D images.

You mentioned the influence of Kerouac’s On The Road. What other influences inform this body of work?

Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, and other writers and artists who were part of the Lost Generation of the 1920s – which is another generation of post-war culture – where creatives were feeling like outcasts with nowhere for them to go, and nobody to value them. A similar sentiment that both Leah and I, and many creatives in my generation, feel today.

I think some of that influence was subconscious, emerging from what we have studied in the past, and the photographers that we know well, and look at, and teach. We are dealing with memory, perception, a sense of romanticism, a way of wanting things to be ok, and I think it expresses a sense there is nowhere to escape, and we are making it up for ourselves.

Since the 2016 election, these images have shifted a little in meaning for us, really bringing forward photography’s element of time. Here is this thing that we value and we are taking the time to document. This is our existence, where we go and travel, and what it is that gives us meaning in our own lives, which is all now under attack. I am always interested in that relationship between the viewer and a photograph.

There’s intention behind the mundane-ness behind these images, the plainness in some of them. While photography oftentimes looks outward to the world, we are looking at those moments where we look into ourselves and we are alone. We form a sense of identity despite the external influences. That’s where a lot of the work comes. We try to develop meaning out of something that, on the surface, seems insignificant.

What’s next?

I’m fascinated by the way people attach emotion and memory to a particular object and how objects become sentimental. In my collaborative project, I’m looking at the way people connect to the landscape, and on my own, I’m looking at their connection with objects. In my series, Everyday Things, I took a 4×5 film camera into private homes to find how people surround themselves with their objects. It focuses on a more domestic and intimate look. I’m interested in that materialism of our own selves as people.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Laura Shill: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 24th, 2017

-

Abbey Hepner: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 23rd, 2017

-

Teri Fullerton: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 22nd, 2017

-

Heather Oelklaus: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 21st, 2017

-

Ashlae Shepler: The States Project: ColoradoDecember 20th, 2017