On Collaboration: Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman

I am so excited to launch a new monthly column by two photographic artists I so admire, Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman. These two talented artists have worked as a collaborative team for their entire photo careers, so I thought that they would be the perfect duo to look at the range of photographic collaborations in contemporary photography. – Aline Smithson

I am so excited to launch a new monthly column by two photographic artists I so admire, Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman. These two talented artists have worked as a collaborative team for their entire photo careers, so I thought that they would be the perfect duo to look at the range of photographic collaborations in contemporary photography. – Aline Smithson

Barbara Ciurej is a Chicago-based photographer and graphic designer. She has a BS in Visual Communications from the Institute of Design+Illinois Institute of Technology. Ever looking to the art historical past to invoke order and harmony, her search for narratives to explain the plight of how we got here has fueled 30+ years of making pictures.

Lindsay Lochman is a Milwaukee-based photographer and lecturer at the University of Wisconsin /Milwaukee. She received her MS in Visual Communications at the Institute of Design+Illinois Institute of Technology. In her quest to organize the natural world, she is inspired by the intersection of science, history and the unconscious.

On Collaboration: Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman

We welcomed Lenscratch’s invitation to introduce On Collaboration, a monthly interview featuring other collaborators, collectives and photographic group projects, all of which will provide a glimpse into the practice of co-creating and sharing ideas through photographic images. We are fascinated by the variety of ways ideas and images merge in the photosphere now and we invite you to join us in our exploration.

Since its invention, photography has lent itself to shared ideas and practice for many reasons, both conceptual and practical. The work of David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson was grounded in their different and complimentary skill sets.

Pioneering wildlife photographers Richard and Cherry Kearton demonstrated the practical side of collaboration as they grappled with cumbersome equipment and unknown territories.

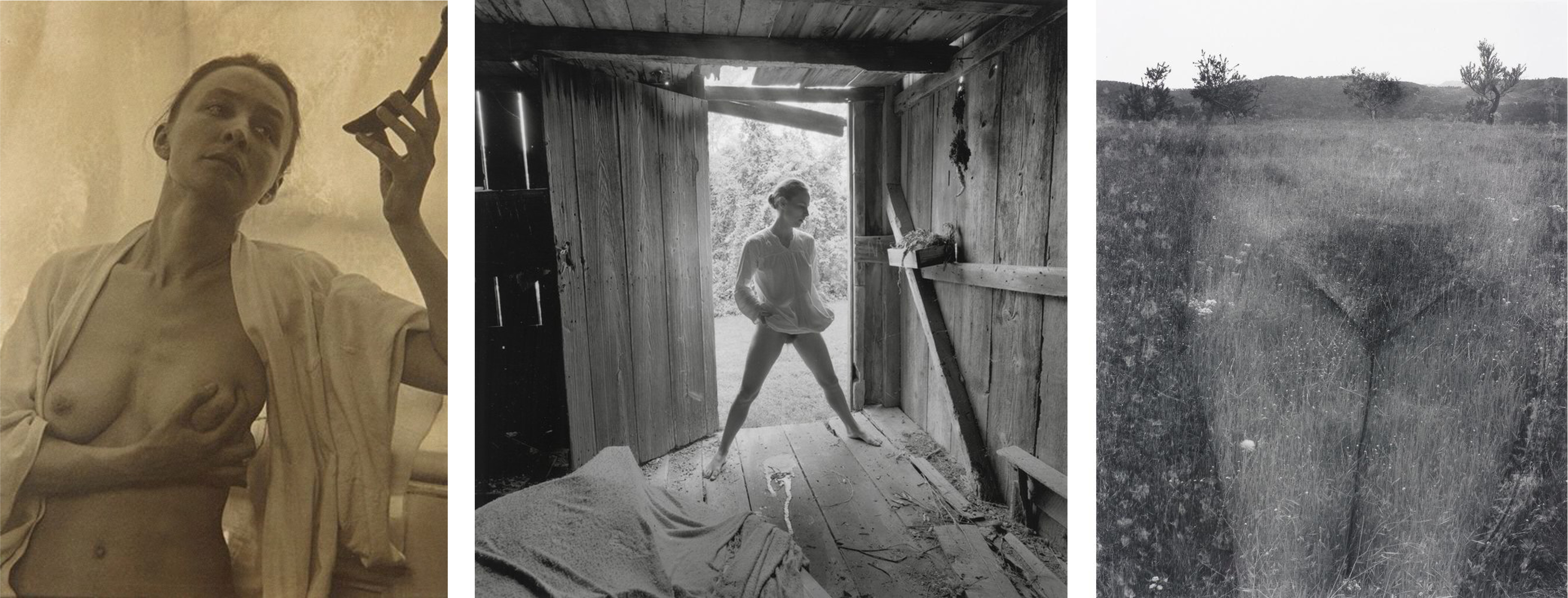

If you expand the notion of collaboration, as we do, models and muses were also collaborators in the creation of significant bodies of work – think Alfred Steiglitz and Georgia O’Keefe, Emmet and Edith Morris Gowin, Harry Callahan and Eleanor Knapp Callahan.

©Georgia O’Keefe by Alfred Steiglitz, 1919; Edith by Emmet Gowin, 1971; Eleanor, Aix-En-Provence by Harry Callahan, 1958

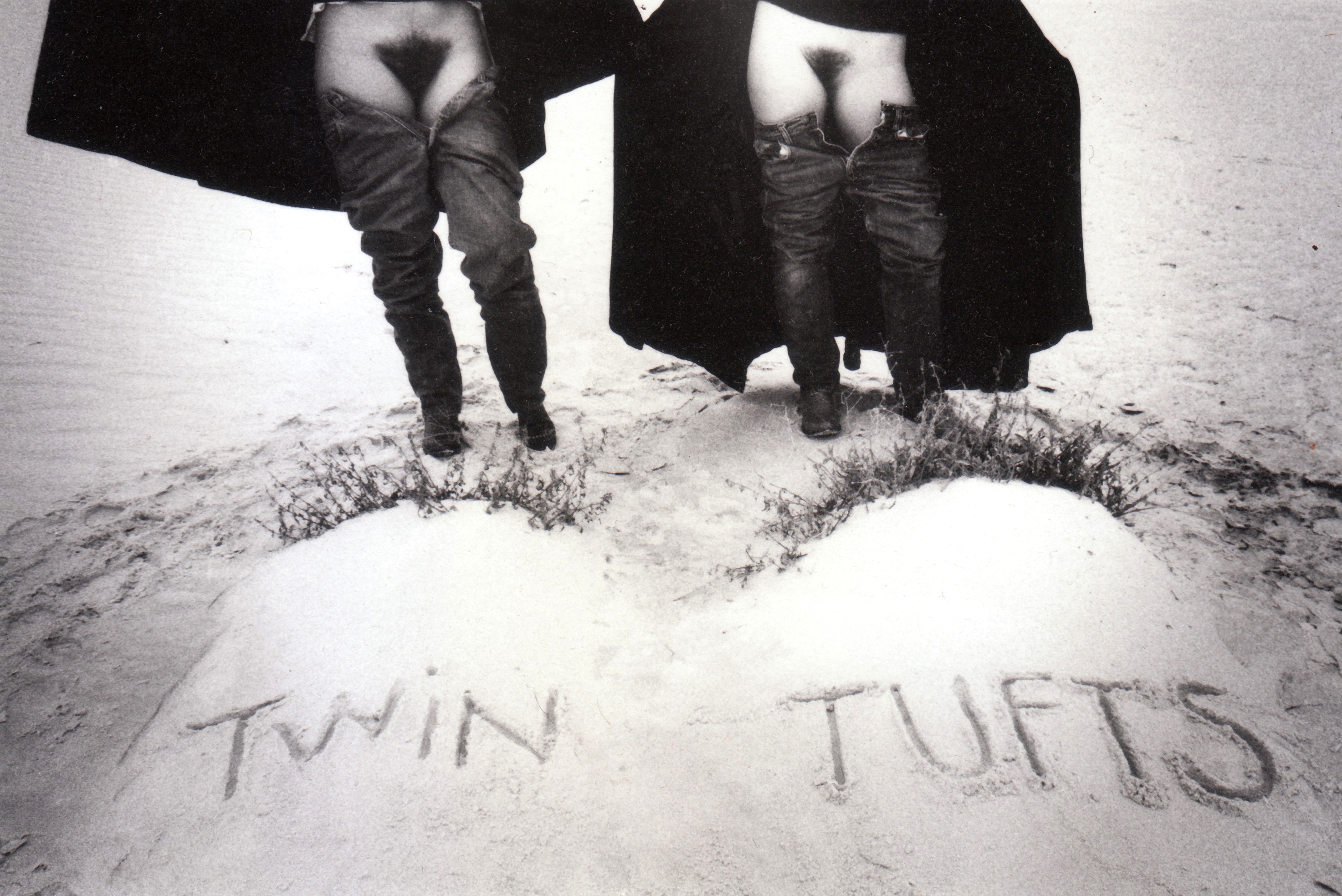

Our own collaboration began in 1977 when we took a road trip to the revered photographic destination of the American southwest. Our first photograph, Twin Tufts, was a serendipitous encounter between tufts of desert vegetation and our own. We have forgotten who thought of the pose, set up the camera or scribbled in the sand, but we both arrived at the same vision. The process unfolded in the fluid way of story telling with details and histories accruing from our own experiences. It began an approach that has carried us forward as we interpret the physical and psychological landscapes in which we find ourselves.

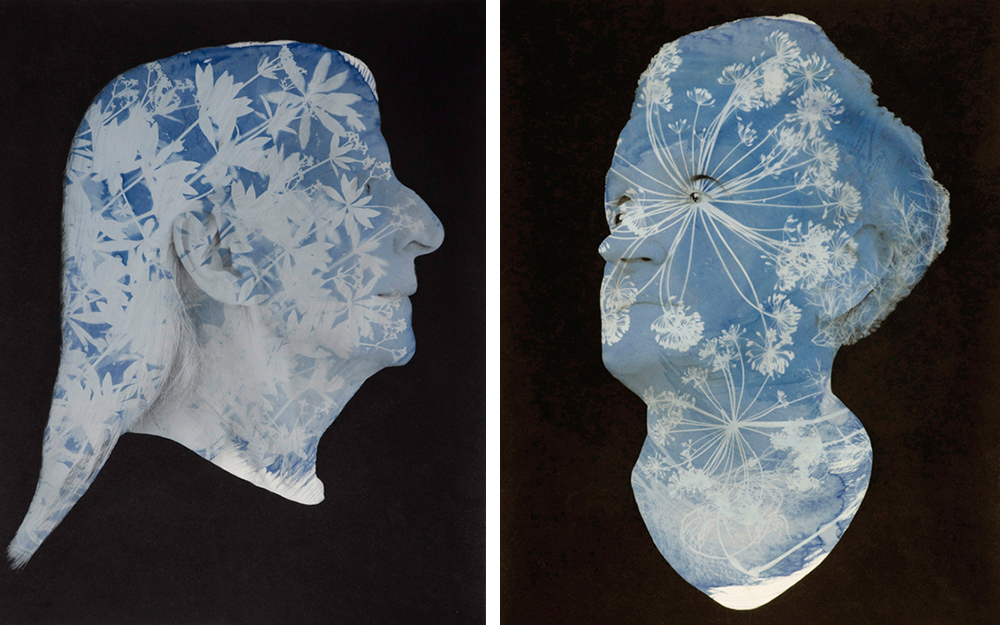

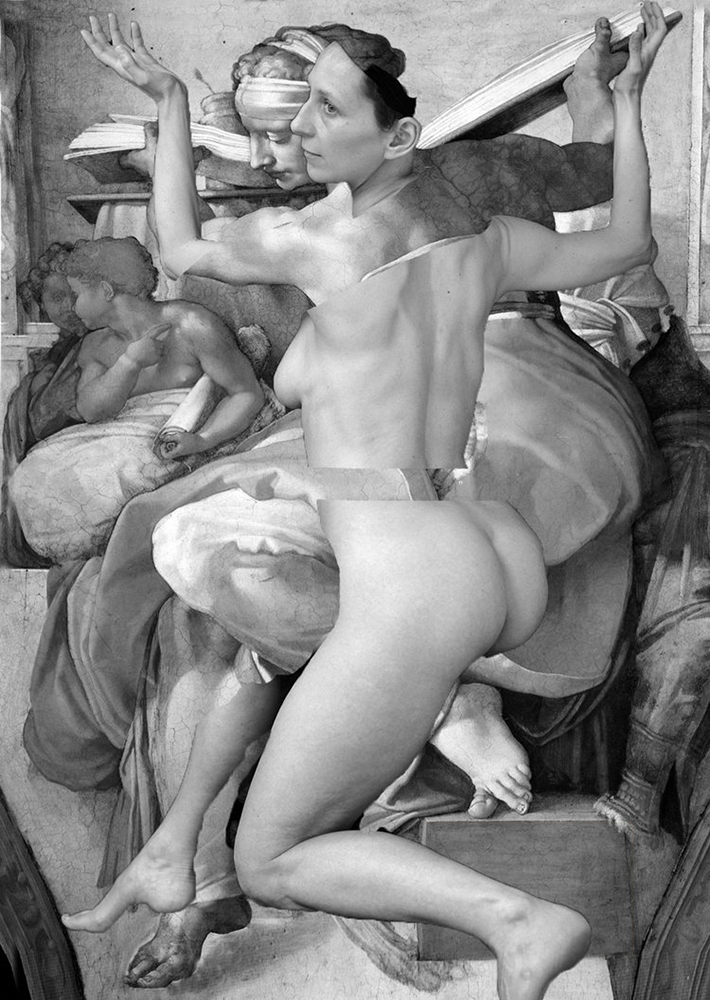

Our collaborative approach to the work varies and is shaped in response to the subject matter. Our abiding interests in layers of history and the constructed landscape as well as a continuing examination of our changing selves are at the core of our work.

What we have learned from our years working together is that a mysterious third ‘voice’ exists in the photographs we make. The mind-meld of our separate visions combines to create works outside of either of our expectations. Our collective vision takes on a life of it’s own. We don’t try to unravel what we each bring to this dynamic.

Kyle Seis’ questions from a recent interview in Generous Magazine which centered on the roles of individuals within a creative union seemed an appropriate introduction into our own practice and we excerpt it here (with permission):

KS: How does a collaborative art practice compare to a traditional marriage?

LL: I’m not sure what a traditional marriage is…like Adam and Eve? Ward and June Cleaver? Maybe you mean a traditional artist marriage, like Eleanor and Harry Callahan?

So consider these comparisons:

We have not made collaborative vows to each other at church or in city hall,

but you must not assume that the images we have produced are illegitimate. We do not have a sexual relationship, but when mind-melds occur, it is thrilling. It may be possible to consider our collaboration to be like a menage a trois: photographs, Barbara and me.

KS: Prior to Barbara, did you ever envision sharing a practice with someone?

LL: Prior to meeting Barbara, I considered myself a potential artist. This notion was not encouraged, however, because it was feared I might turn out like my artist Aunt Cordelia. Our collaboration was neither premeditated nor a common way of making artwork at the time. After so many years, it remains very organic in its structure and somewhat mysterious, even to us. It’s not an arrangement for the faint-hearted artist.

KS: What were you making before connecting with Lindsay?

BC: I was obsessed with a pair of red spiked heels that belonged to my mother. I was setting up and photographing narratives starring the shoes. Turns out Lindsay fit into those shoes. I was also working on a project trying to picture infinity.

KS: What are the biggest differences between you and Barbara?

LL: Our brains. Although we share a similar visual aesthetic and production standards, differences can be seen in the way we process information and in our working methods. My work is a non-linear embrace of ideas, processes and research which I combine and transform through manipulation. I produce objects and images for evaluation. Barbara is wide open to experience, fulfilled by communication and interaction with humanity. Her process displays focus, patience and optimism.

KS: What have you learned from Lindsay?

BC: How to argue. I used to back away from arguments but now see them as part of a rigorous practice. There is tension in collaborating but good tension that suspends the work between our divergent points of view. We argue over everything – from exasperatingly trifling topics like how small is a small dog to big issues like social responsibility. Learning to reason through and defend your choices is articulation of vision.

The value of experimenting. Lindsay is a tireless experimenter. Just when I think we are finished with a project, she will tear it apart, print it backwards, turn it upside down, see what happens if we bend the frame. I am more reluctant to do that but admit that approach yields surprises and pushes the work. Even when we throw away all the experiments, there is a sense we have left no stone unturned in testing the work.

An irreverant attitude. She has always had a more heightened worldly sense while I tend to float in idealism. I have learned to do more research and critically question assumptions, canons and historical narratives, which is essential to the projects we produce.

KS: How has living in different cities affected your process?

BC: Double everything. Because we can be in two places at the same time, information multiplies and migrates. Spheres overlap. I appreciate that distance gives space and time to think and research separately before coming together in the studio. As I make the two-hour trek from Chicago for a stay at the studio in Milwaukee, it is a welcome meditative interlude.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025