Lisa Kereszi: The States Project: Connecticut

I first met Lisa Kereszi at the 2013 Northeast Regional SPE Conference in Portland, Maine. I was there to give a presentation on my work titled “Troubled by Beauty“. Lisa was the keynote speaker and spoke about her now well recognized Joe’s Junkyard project. Like so many others, I was captivated by her story telling and careful to observe how she used of the photographic images she was making to connect with the audience. I met her again as she came to land at Hartford Art School and teach in our Limited Residency MFA Photography program. Lisa is a force in the photographic community at large and certainly one we cherish here in Connecticut.

Lisa Kereszi was born in 1973 in Pennsylvania and grew up in Suburban Philadelphia to a father who ran the family auto junkyard and to a mother who owned an antique shop. In 1995 she graduated from Bard College with a Bachelor of Arts, finally settling on a concentration in Photography after double-majoring for a time with Literature/Creative Writing, in which she concentrated on poetry.

After college she moved to New York City and worked as an assistant to Nan Goldin. In 2000 she received a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Yale University School of Art in New Haven, Connecticut. She has been on the faculty there as a Lecturer since 2004, and was appointed Critic in 2012 and Director of Undergraduate Studies in Art in 2013. She was a 2010 National Endowment for the Arts MacDowell Colony Fellow.

Her work is in many private collections and in that of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Study Collection at the Museum of Modern Art, the Altoids Curiously Strong Collection of the New Museum of Contemporary Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Norton Museum of Art, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the Berkeley Art Museum and the Yale University Art Gallery, among others. Her work has been shown in group shows at the Whitney Museum, MoMA, the Aldrich Museum, the Bronx Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Queens Museum of Art, the Berkeley Art Museum, the Urban Center Gallery at the Municipal Art Society in New York, among others.

She had solo shows in 2002 and 2003 at Pierogi in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. She is represented by Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York, where she had Winter 2005, Spring 2007 and Spring 2009 and 2012 solo shows. Solo museum shows include the recent exhibition, Joe’s Junk Yard, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, installed in the Mike Kelley Mobile Homestead, and previously at the Matrix Gallery at University of California Berkeley as part of the 2005 Baum Award for Emerging American Photographers.

Her editorial work has appeared in many books and magazines, including The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, Nest, New York, Harper’s, TIME, W, The London Telegraph Sunday Magazine, Details, GQ, Black Book, Jane, Newsweek, House & Garden, Nylon, Bon Appetit, zingmagazine, wallpaper* and others. Her pictures regularly appeared in the New Yorker’s “Goings on About Town” section for several years. She was included in the 2003 list of the 30 top emerging photographers by Photo District News, and was granted a commission to photograph Governors Island by the Public Art Fund the same year, which culminated in shows at the Urban Center Gallery and the Mayor’s Office at City Hall and a 2004 exhibition catalog, Governors Island, as well as a permanent installation on the island. Recent curatorial projects include 2014’s exhibition and catalog, Side Show, at the Edgewood Gallery at Yale, which investigated the intersection of carnival sideshow culture and visual art.

Four monographs are in print – Fun and Games with Nazraeli Press in 2009, and two with Damiani Editore: Fantasies in 2008 and in 2012, Joe’s Junk Yard, which was released in early Fall 2012. Released in 2014 by J&L Books is an artist book as an offshoot of the junkyard book, entitled The More I Learn About Women. Kereszi lives and works near New Haven, CT, and is working on two new series about family – the old and the new ones.

Xinjiang: The West of China, Security and Spectacle

This past summer, I was lucky enough to have the chance to visit the tightly-secured region of Western China known as the Xinjiang autonomous region. Knowing little about it other than that I would be visiting various points along the Silk Road in a van with a group of American artists and our hosts, I allowed myself to be whisked away on long, long drives through long, large expanses and unreal mountain ranges and grasslands. En route, in between the most sublime mountains, grasslands and clear lakes, we stopped at tourist traps – several sanitized, but not spotless and seamless, versions of a Kazakh Village, a Mongolian yurt and craft display, a wonderland of grapes, a representation of a mythical tale complete with camels and costumed characters, and a movie set in a surreal desert complete with prop weapons to pose with.

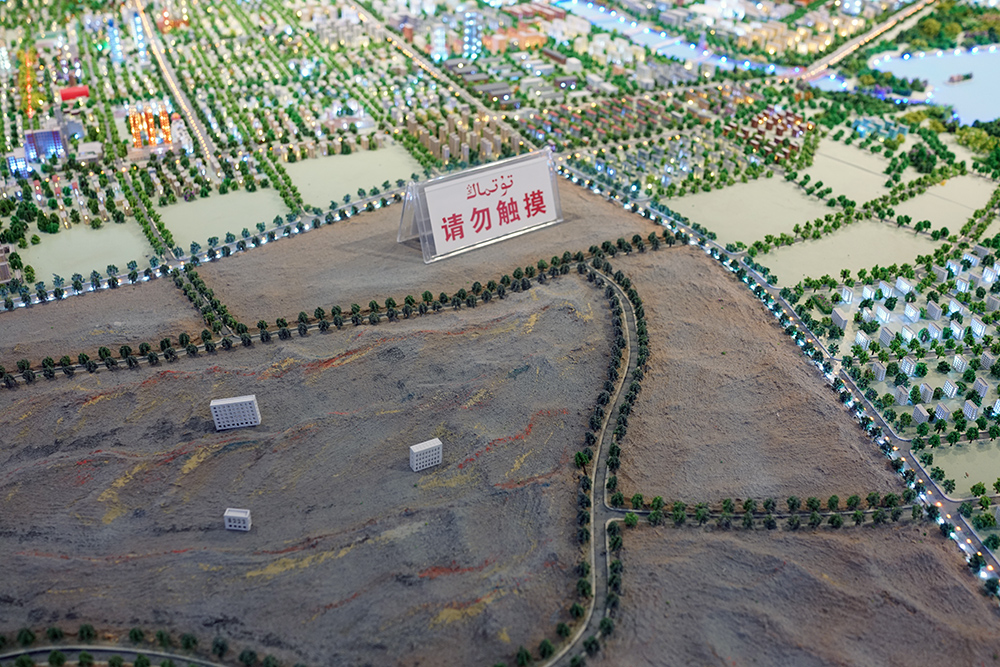

In between and at these cheesy locations in the midst of great natural splendor, our group witnessed the obvious evidence of a massive security effort aimed at tightening the Chinese government’s grip on the Uighur people of cities like Urumqi, Turpan, Karamay, and all checkpoints in between. Security cameras, armored staff and x-ray machines were everywhere, even in small restaurants and hotels, and bus passengers at gas stations were forced to disembark and wait outside of barbed- wire patchwork fencing. Security theatre was aimed squarely at the centuries-old, Central Asian Muslim populations who are now being pushed out by quickening migration west of Han Chinese. This show of force seems to have quelled the violent uprisings of the recent past, but we had to ask ourselves – at what cost?

My photographs show this juxtaposition of history and culture with this push for change and growth of a 21st century society with newly-disposable income, as the government sanctions the building of spanking-new, post-industrial resorts and gleaming cities of the future, intended to create one China with one belt across, diminishing the vibrant cultures that have inhabited this awe-inspiring land for centuries. Go now, look now, or forever hold your peace.

How is this work different than the work you usually make?

I think this was more like an assignment, but without a client. I guess I was my own client, in a way. I say that because there was, to be honest, a bit of a hit-and-run quality about it. I have worked that way previously on assignment for magazines as wide-ranging as the New Yorker and wallpaper*, spending as little as 15 minutes (Robert Altman and Garry Trudeau for TV Guide) or as much as several weeks, spread out in several trips (an investigative story on sex tourism and trafficking for GQ); whereas on my own projects, I may only spend an hour or several at a single location, but those individual shoots are usually part of a much bigger, themed project that encompasses many, many hours of shooting. Whether it is very personal (Joe’s Junk Yard series about my family’s business) or a broader project that has many pieces, I go back to he same kinds of places and work a little bit serially until I feel like I have found what I need to say or show something poetic and vital and original. On those bigger bodies of work, like Fun and Games and The Party’s Over, I have returned again and again to the kinds of places people go to in order to escape reality, which means a whole bunch of cumulative hours spent in theaters, nightclubs, bars, strip clubs, haunted house attractions, all usually during the daytime hours. But in a case like this, there was not really a chance for sustained practice, only for this photographer to react in the moment and try to craft something based on my own personal reaction to what I encountered. I had only previously been to China and Central Asia once each, so I had no real personal stake or any deep knowledge about what I was encountering, only my gut reactions as an artist. This could be seen as problematic, because I was essentially a reluctant tourist, but I don’t purport to be a documentarian, even if I am referencing current events and international politics in the subject matter. I felt like I could do nothing more to get through the long days of regional travel and tourism than to take pictures to try to make sense of it all for myself.

In the past, I repeatedly found myself sent to Florida and also to former Soviet-controlled countries – for assignments or for artist exchange or residencies. I culled together images from those repeated visits into two series that I have only shared on my website, as Sunshine State and also Post-Soviet, but I am not sure what to do with them outside of those contexts, except use some of the images elsewhere that relate to the escapist series, which of course, some do. What is more a manufactured place of escape than Florida, the last resort, in many ways?

What is your relationship to documentary practice?

Photographs are inherently “documents” since they can act as evidence of existence; they are indexical. Light bounces off of something and records that it was there through a chemical process on photosensitive material, be it film or a chip or whatever hasn’t even been invented yet. That’s why I think it’s such a vital medium – it calls into question reality, while at the same time affirming it. That ambivalence or dichotomy is really exciting to me. My favorite photographers (Evans, Arbus, Eggleston, Frank) could be easily misunderstood as purely documentary photographers; and yes, they were following a practice that involved documentation of reality, but it’s all filtered through the eyes, mind and hand of he photographer. We are not machines, so it has to be colored with our experiences somehow. I love explaining that to students, about how this medium is not what it seems when one walks in the door of an Intro Photo class, but is actually a means to express how every moment of your life and thing that’s happened to you, whether joyous or traumatic or in between. All that stuff affects how you literally perceive the world, and affects your choices when making a picture. And every piece of art you’ve seen, book you’ve read, every image you have ingested, it all forms into this puree, no, a primordial soup, from which you can draw something I guess they call inspiration. That is one of the biggest things I learned in grad school – that pictures are lies, in the best sense of the word. They are not true, they are filtered pieces of art. That was Tod Papageorge’s thesis that grew all of these incredible, important photographers out of the program at Yale.

Why did you choose this work for this feature?

I didn’t want to put back out there just a reformat of work that an be found elsewhere online. I also don’t feel ready to present the new work surrounding family and being a mother. It’s still gestating, if you will, and I am not even sure it will make sense to anyone else anyhow. I thought his was an opportunity to show work that doesn’t really fit in with anything else I am doing perfectly, and I am not sure if this work will see the light of day anywhere else. I feel like there is a sense of urgency with he subject matter, too, and that this work should be out there as part of the dialogue about the region and the cultures at risk. I am not sure how many Westerners are even aware of the situation, much less visit. When we were in these very remote places, I was curious how often a dirty American backpacker comes through – is it once a month, or is it every day? I wished I could stay and find out. Myself and the other artists on the trip (all painters) really just wanted to be dropped off and stay put for weeks at any number of places, usually the “old town” in any given city, which will probably be demolished within a couple years from now. What I think we missed on this trip was he opportunity to actually immerse ourselves in the culture, and see and feel how people live there. But it wasn’t that kind of visit, but it could end up being scouting, in a way, for future, more sustained practice. I’d go back for the food alone, which was incredible, and then the pictures, maybe second.

Does it relate to past projects, and if so, how?

I think it only relates in that I was frequently looking at the spectacle and the facade, as I do in my other work, but in his case, it was at the spectacle of propaganda and security, rather than at pure entertainment. There is an aspect of escapism, too, in being made to feel safe from unrest and crime by all the guards and checkpoints, and distracted, too, by the touristic Epcot Center-like cultural displays. My compatriots on the bus immediately had my number, and by day two, one of the jokes was that I was queen of the fisheye, or side eye. Once this was explained to me, I had to agree somewhat that that was how I tend to approach almost everything I photograph, with pause and a sense of healthy suspicion and even criticism, questioning whatever veneers would be presented before me. With photography I can express my own personal doubts about accepted traditions and conventions by shining a light on something that may otherwise go unquestioned publicly.

How do you see this work being finalized… is there a particular vision you have for presenting the project?

I haven’t gotten that far. I would love to have an extended portfolio of these published in a magazine. But I don’t see it as a book or exhibition without a curator or writer attached who has a deep knowledge of the region and can help edit the work in a way that says something greater than what I think I know. A hope would be that the pictures encourage people, particularly young people, in Western China to document their lives and show the rest of the world their multitudes before it is too late. This is really a fast-changing place, but the change doesn’t feel organic or natural.

If you were to choose another vehicle besides photography to speak about these same issues, what might that be and why?

I don’t think I would be equipped to do that with writing or something other than photography in this case. I have written some on other subjects, and also curated a couple shows on topics I care about, but I couldn’t see investigating this subject another way myself. One of the other artists on the trip, painter Tony Shore, tried to go off-road as much as he could and hang out with working guys well after hours at restaurants, bars and a karaoke club. With the memories and iPhone photos he took, he is making drawings and paintings of those people he met.

I could envision something related to what I described previously about getting the world to know the culture better, but doing it through their eyes. If I had the time and the wherewithal, it would be exciting to facilitate a new kind of photographic community there, in the way someone like Wendy Ewald works, putting cameras in people’s hands, and their words on the images. Our work was exhibited in 3 venues in 3 cities all very far apart. I have no idea how my work was actually received, as the only photographer represented, and especially as a photographer of the mundane and the ugly, not as someone representing the beauty of the natural landscape and the people. I think that was definitely something my work was up against, and to a greater degree there than here, because of a traditional and Taoist sense that I encountered in the certain museums and galleries we were brought to, which were not at all part of the urban contemporary and international art scene. What the people (People’s Republic and otherwise across the globe) want, generally, is the pictorial. Most think, why look at something mundane and in the gutter, when you can look at a thing of beauty? But what I hope is that my visual sense of what is beautiful in sadness is something that is actually universally understood, if a viewer takes the time to stop and think. At one of our venues, schoolchildren were brought to draw from our work. Dozens of kids were huddled around the work of each of the painters, but I only had two children, a boy and a girl, doing pastel drawings from my photographs. I absolutely loved these two kids. It was thrilling to me to have one drawing a picture of my grandmother’s car with her Jesus Is Lord license plate, and the other one turning the patterned blue carpet of the old York Street Cinema in New Haven into a floral design. They are now gone – my grandmother passed away, and her car was junked, and the movie theatre has been closed since 2005, now a t-shirt shop nestled in between Urban Outfitters and the Apple Store. These things are gone from this Earth, but a version of them lives on on someone’s fridge halfway across the world. My grandmother never even stepped on an airplane, and here she is, celestially traveling to China.

How does your administrative work at Yale and teaching in the graduate photography program at HAS, impact your work as an artist?

Well, the administrative work, to be honest, has one negative impact, in that it takes up my precious time. In between being a parent, an educator and an administrator, it leaves little time for me to be an artist, unfortunately. I find it very hard to switch gears, and if I don’t have a stretch of hours, uninterrupted, laid out before me, I find it hard to concentrate and actually make work. Right behind me right now are piles of things that need to be photographed for my next body of work, and photographing them will be very straightforward, once I can carve out the time to physically do it. That said, I have the problem-solving skills and experience and sense of duty to do what needs to be done for the undergraduate art department at Yale, and there is great satisfaction in helping have a hand in creating a new generation of educated, well-rounded and sensitive young artists. These young people are lucky enough to be on deck to be the future leaders of tomorrow. But so many of them have so much pressure put on them, familial and cultural, that making art long-term may not be seen in their families as a respectable or viable enterprise. I see that all the time, and I have to help them find a way to be strong and go with their guts if their guts are telling them to make art or support the arts as a career. If I can have any impact on the world, I hope it is in infusing their sensibilities with a deep appreciation and understanding of visual art along with, perhaps more importantly, a deeper sensitivity, through photography, for what it means to be human. Students must go out to into the world to make pictures, and one assignment is to photograph a stranger, and another is to photograph in a place you have never been before. In making students go outside of their comfort zone geographically and physically, I hope to enable them to empathize with their own and other communities well enough to have a harder time doing something with their lives that is not in some way an act of giving back.

What’s next?

I mentioned time as an issue for my practice, and I developed a project during my daughter’s first two years of life that could be made with her at my side. Another project is in the planning phases. I have endured the losses of two people close to me, one after another, this past year: my grandmother and then my father. I have been barred from the property and kept from many of their things by an unstable person, and have had to grasp onto any little scrap I can get to feel some sense of closeness and control. While still settling in to my new role as a mother, this blindsided me, and has put to the forefront of my mind the trauma that gets passed on from generation to generation, and how we, as parents, must work to stop the cycle of damage. It’s easier said than done. That idea, along with the sense of home as a safe place, and as a resting place for memory are what will drive this body of work. I will also focus on and the cycle of life and death. I am currently editing some previous work related to the subject of preservation and home, and have a list going of the pictures that need to me made to fill in the holes and tell the story I want to tell. I feel a little like Arbus with her lists, and I have never worked that way before, but it feels right right now. I know what I need to do, but I just have to do it, as soon as I both have the time/resources, but also feel emotionally ready. I am pretty confident of this future series doing what I need it to do, including connecting with anyone else (i.e., everybody, a some point) who has ever lost anybody and had their things left behind function as an insufficient stand-in. My previous work about family has also been an endeavor to salvage what has been painful or lost, and this will be another version of that, which I hope has universal appeal.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael Vahrenwald: The States Project: ConnecticutMarch 31st, 2018

-

Mary Frey: The States Project: ConnecticutMarch 30th, 2018

-

Joan Fitzsimmons: The States Project: ConnecticutMarch 29th, 2018

-

Marion Belanger: The States Project: ConnecticutMarch 28th, 2018

-

Lisa Kereszi: The States Project: ConnecticutMarch 27th, 2018