Photographers on Photographers: J.K. Lavin and Darryl Curran

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we are happy to share this interview with J.K. Lavin’s interview with Darryl Curran. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

I first met Darryl Curran when he was teaching a class on alternative processes at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) extension somewhere around 1973 or 74. The photography world was a micro version of what it is today. A few years later Darryl agreed to be one of my graduate advisors when I enrolled at California State University Fullerton for a graduate degree in photography. It is a privilege to interview someone who has been involved in photography for so many decades as an artist, curator and educator and who has so much knowledge about the medium. He has an impressively extensive resume dating back to the 60s when he was a student of Robert Heinecken at UCLA. Darryl Curran’s work has been included in many important and historic exhibitions and is held in many major collections. He was a significant participant during a period of photography that set the foundation for what photography as an art form has become.

I would love to be able to list the photographers that Darryl has shared a meal with or offered a ride to for a conference or a gallery opening. It would read as a Who’s Who in Photography. He has always been very generous in sharing information and has helped to expand the photographic community. That’s in addition to continuously creating work for over sixty years and being an educator for decades.

Darryl Curran has two upcoming solo exhibitions in the Los Angeles area:

A Moment in Photo History opens in September at the As-is Gallery, 1133 Venice Blvd, Los Angeles 90015, 2:00-5:00PM.

He is represented by the dnj Gallery in Santa Monica and will be having a solo exhibition there in early January 2020.

Darryl Curran has been active in the fine art photography field since 1965 as exhibitor, curator, juror and board member of several arts organizations. He joined the CSUF faculty in 1967 and initiated the Creative Photography B.A. and M.A. program and co-authored the M.F.A. curriculum. He served as Department Chair from 1989-99 and retired in 2001. Curran’s creative work is housed in major public collections and has been included in numerous important group shows such as Photography into Sculpture and Mirrors and Windows, Museum of Modern Art; Vision and Expression, International Museum of Photography/ George Eastman House; Photography into Art, British Arts Council; Light and Substance, University of New Mexico; Extending the Perimeters of Twentieth Century Photography, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Photography and Art/Interactions since 1946, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Fort Lauderdale Museum of Art; Lost in Found in California: Four Decades of Assemblage Art, G. Ray Hawkins Gallery, Los Angeles; Proof: Los Angeles Art and the Photograph, Laguna Art Museum (traveling). In 1995 he was invited to Madrid to represent the USA and the participating artists at the opening of Empowered Images, a cultural presentation of the United States of America, a traveling exhibition of contemporary photography.

As president of the Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies (LACPS) he lead the effort to produce 10 Photographers/Olympic Images, a project sponsored by the Olympic Arts Festival and exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art. He curated exhibitions such as Graphic/Photographic, CSUF, 1971; 24 from L.A., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1973: with Eileen Cowin, Object, Illusion, Reality, CSUF, 1979: Photographic Visions, LACPS, 1984: and Image as Object: Photographic Reality to Photographic Experience, Brea Civic Center, 1991.

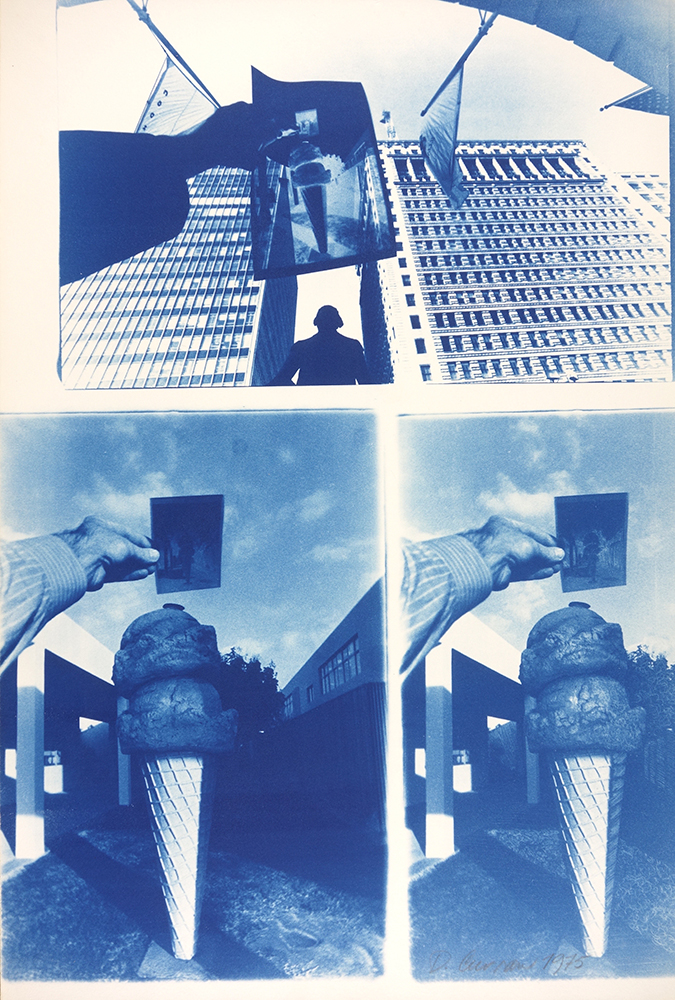

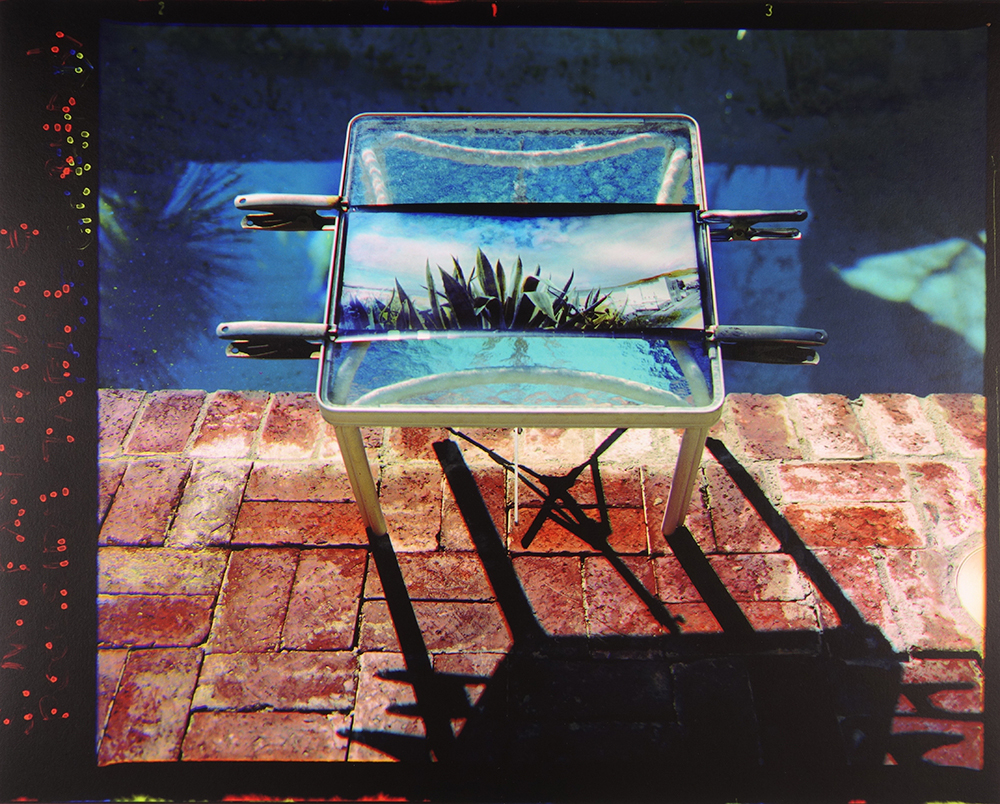

I started this work in the late 1970’s. Influenced by Paul Outerbridge, I set out to make my own color photographs in an old fashioned way, with camera separation. Creating photographs in this manner encourages inaccuracy and serendipity, mistakes and happy accidents. Using the triad color filters; red, blue and green with black and white film I was able to re-create the original color of the scene via Kwik Print (a non silver process), photo silkscreen or preferably, the dye transfer process.

I had been including black and white photographic prints as a formal device in the frame of my pictures for several years. For the color photographs I continued that idea as an insert into the swimming pool images. I also knew that the motion of the water would not been captured accurately in the three negatives and I expected “happy accidents.”

The dye transfer process is exacting and accidents are not always happy.

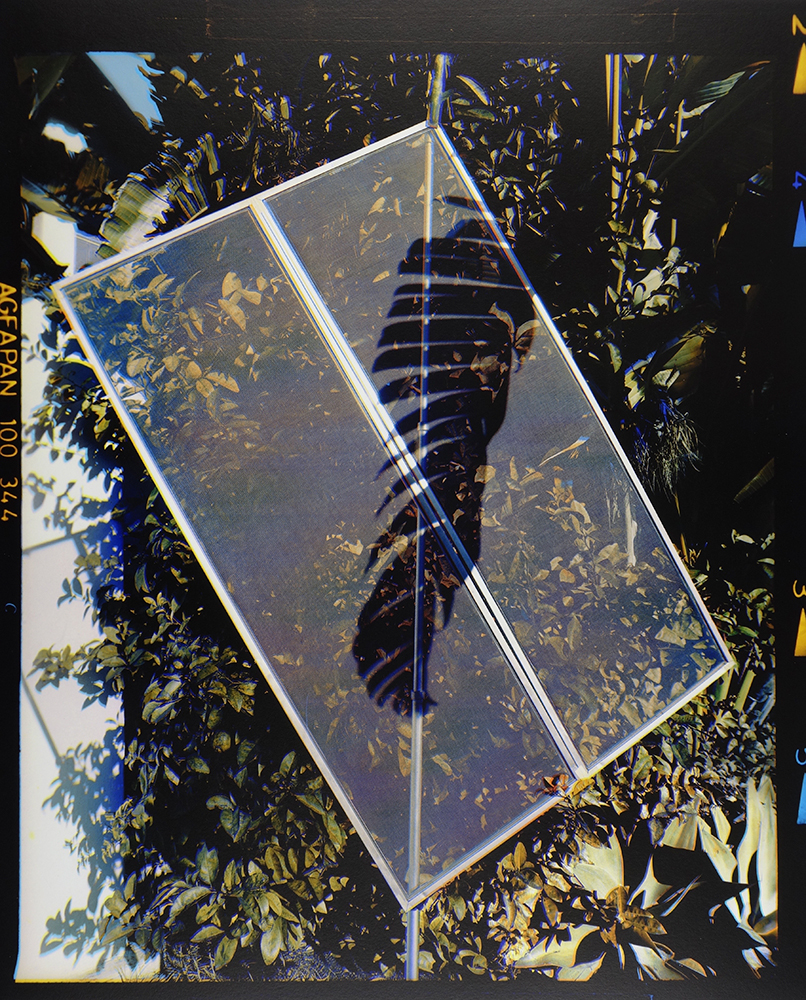

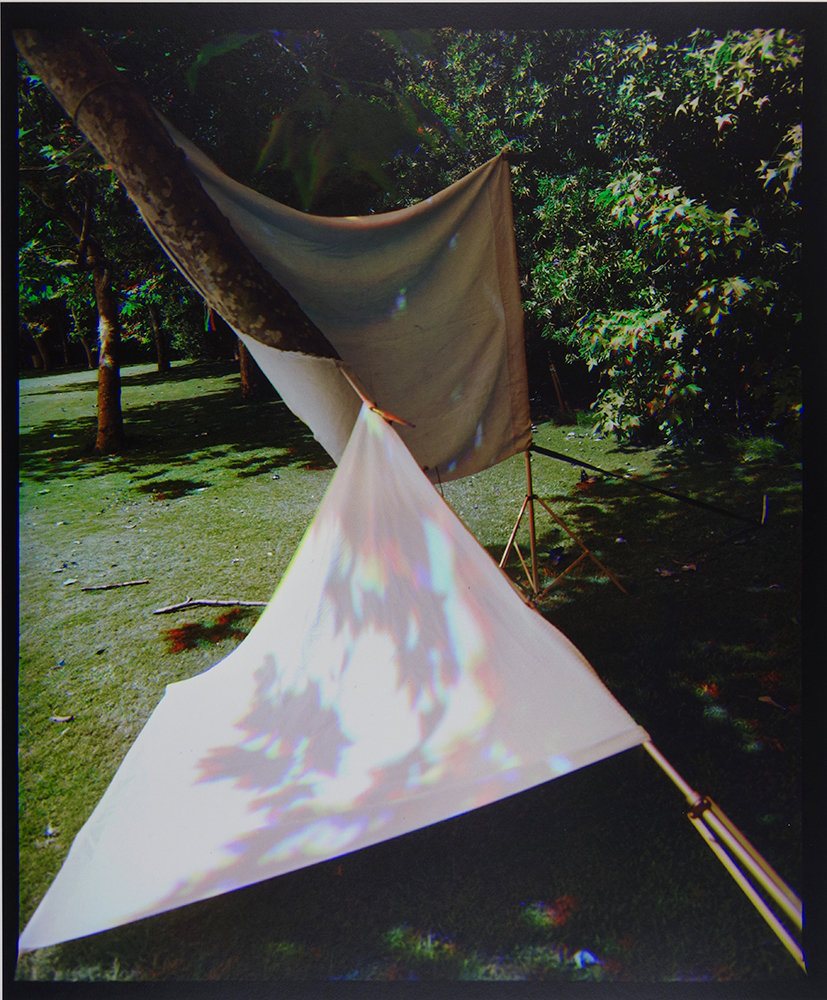

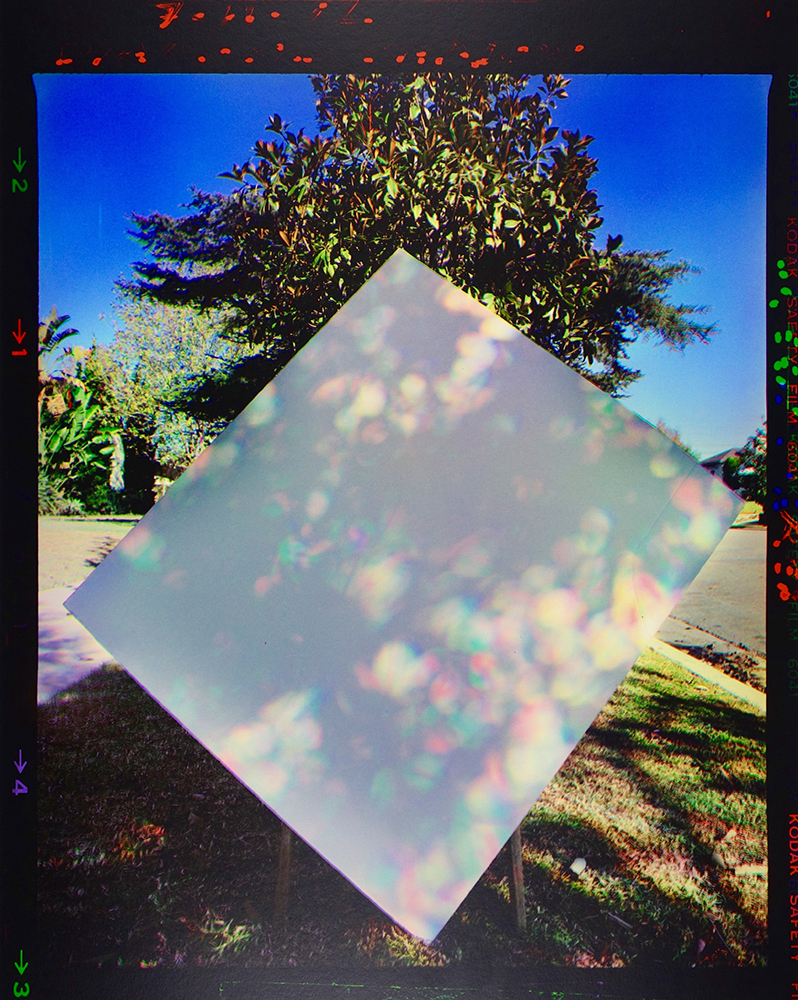

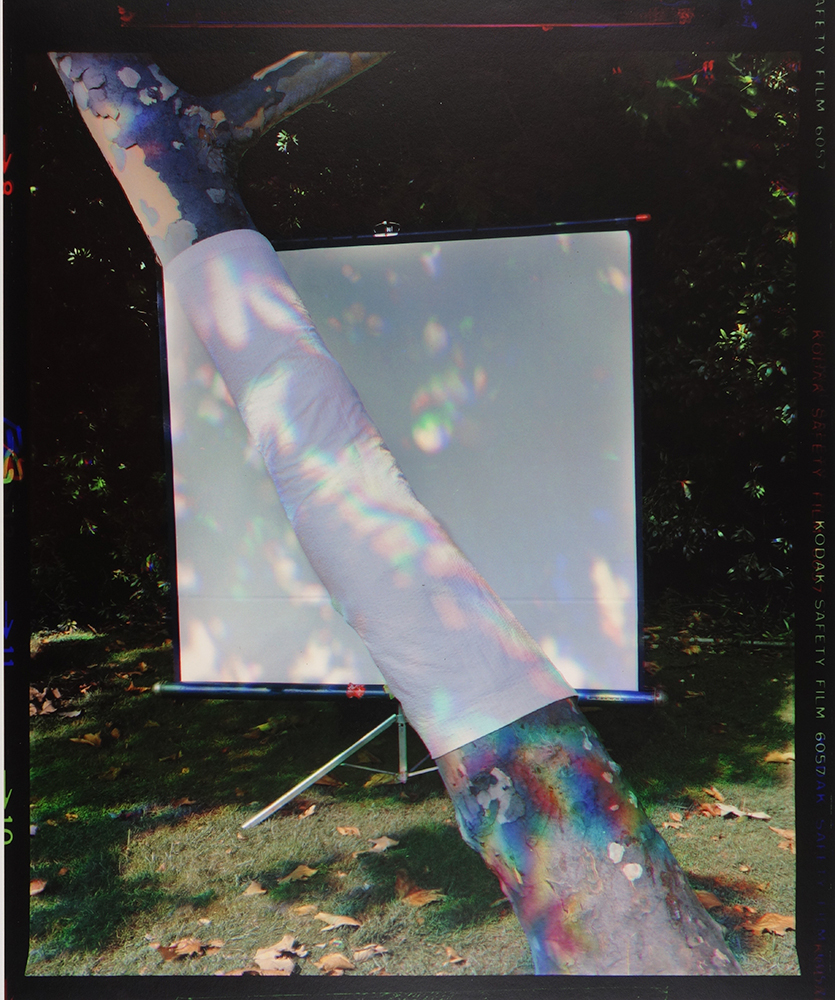

I continued photographing with the color filters, focusing on shadows cast on white surfaces. Gray shadows are produced from the main printing colors, cyan, magenta and yellow. I was interested in how they would be represented in the elapsed time of the three camera exposures. White surfaces are not always available. I used an old portable projection screen to pose as shadow catcher and metaphor for “showing slides”. I wrapped white fabric around tree trunks as a visual foil to the projection screen while investigating the diagonal compositional device.

One of the frustrating aspects of working in this manner is that I couldn’t evaluate imagery. Three black and white separated negatives don’t reveal their color potential unless they are recombined into color. These negatives have been stored from 1982 until 2012. New technology rescued them. They were scanned and digitally printed into working proofs and final prints made in 2014.

J.K. Lavin: Tell us about your growing up and how you first became involved in photography?

Darryl Curran: I grew up in a normal household, mom, dad and a younger sister. We lived in Santa Barbara until WW II when my dad opened a restaurant in Port Hueneme CA in 1941 or 42. Art did not play an important role in my upbringing except that my mother’s parents were very talented in various crafts – woodworking and wood turning, lapidary, silver casting and leather tooling. I suppose the notion of making things stems from learning from them during my summer visits. My grandmother had made cyanotypes on fabric while living on their rural Montana farm in the early 20th century. I didn’t know what a cyanotype was at the time but I was intrigued that a photograph could appear on a pillow cover.

The G.I. Bill supported my art studies at Ventura College and later at UCLA. I concentrated on graphic design and was introduced to photography by adjunct Professor Don Chipperfield. Robert Heinecken was hired as I entered graduate studies and I continued photographic experiments under his guidance. He encouraged me and fellow grads Pat O’Neill, Bruce Houston and Carl Cheng to pursue the creative potential of the photographic medium.

I graduated with an MA in 1964, worked in the UCLA Art Gallery for a year and took my first trip to Europe in 1965 where I stayed on for fourteen months, traveling to the Middle East, North Africa and Scandinavia.

JKL: Could you give us a description of the photo world at that time and how it has changed?

DC: Photo world: When I was enrolled at UCLA I was unaware of any photo world until Robert Heinecken showed me Aperture magazine and introduced me to a new organization for photography educators which evolved into the Society for Photographic Education (SPE). SPE spearheaded fine art photography into academic institutions, museums and art collecting circles throughout the 1970’s and ’80’s.

In the 1960’s and ’70’s photo courses were in great demand in college and university art departments. I was fortunate to e hired by the Art Department at Cal State Fullerton to develop a fine art based curriculum. Although there was great enthusiasm in the education world there was not much interest for photographs by art museums, art galleries or with art critics. Exhibitions of photography were mainly curated in college and university art galleries and a few independent galleries. Suda House, Diane Weisman and others formed an organization to serve growing interest in the medium in 1973. Later this became known as the Los Angeles Center for Photographic Studies (LACPS), and opened with exhibitions in the gallery of Cameravision on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood. Otherwise there were not many venues for contemporary photographic work to be seen or experienced.

Change: Today photo galleries are like Starbucks: there is one on every corner. The introduction of digital cameras and smartphones have led to massive interest in photo image-making. Photo expos, such as PhotoLA, often feature fashion- or illustration-based photographs rather than subjective, challenging, thought-provoking imagery. However, the future looks bright for photographic innovation. New technology has made so many tools available to creative minds, we just have to sit back and see what happens.

JKL: Who or what do you consider as a major influence in your work?

DC: Influence: I can’t place one single influence on my work. I like to refer to influence as my friends, colleagues and inspirations. My first art history course introduced me to Abstract Expressionism. I was especially drawn to Franz Kline’s paintings, David Smith’s sculptures and Rauschenberg’s combines. At UCLA I saw Ingmar Bergman’s “Seventh Seal” and Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai”, both intensely moving and made a lasting impression. As far as photographers, there are so many: Frederick Sommer, Aaron Siskind, Imogen Cunningham, Lee Freidlander, Bart Parker, Ken Josephson, Robert Fichter and many others.

JKL: Robert Heinecken was a prominent figure and influence in photography, especially here on the West Coast. Could you tell us something about meeting Heinecken and your relationship to him first as a student, then colleague and friend. Do you have a favorite Heinecken story or recollection?

DC: There are too many Heinecken stories to relate. He was both serious and funny. Jokes and hijinks were his trademark yet he was extremely serious about his work and career. And also serious about his teaching. He studied art and design. He was a good graphic designer and contributed many catalog designs and entrance panels for the UCLA Art Galleries. He was a charter member of SPE and championed its cause throughout his life. He supported LACPS through pro-bono lectures and exhibitions. His house was a gathering place for visiting photographers, curators and collectors. He hosted many parties and dinners which allowed for local photo enthusiasts to mingle and connect with them and each other.

Favorite story: We hosted a western region SPE conference. He was the chair and I was co-program director and the conference was held at Cal Arts, at the time a new facility. We selected the legendary photographer, Walter Chappell, to be keynote speaker with Jerry Uelsmann as featured photographer. Heinecken called me in a panic the afternoon of the event’s opening. He needed me to come to his house immediately.He didn’t explain the urgency, just get over there. When I arrived he and Uelsmann were trying to calm Walter Chappell who had arrived with his twelve year old son from San Francisco. Walter was very intoxicated and the key to keeping him from going back to the airport was bribing his son to intervene. Heinecken and Uelsmann had to make another trip to LAX to pick up other attendees. My job was to get Walter and his son to Cal Arts in time for his keynote lecture and it didn’t look as if I could manage it. At last we arrived at Cal Arts, checked in with registration and collectively took Walter and son to dinner. Heinecken was trying to keep Walter under control and suggested that everyone abstain from drinking alcohol. Walter stood up unsteadily and started to remove his pants, much to the shock of restaurant patrons. Heinecken summoned the waiter and quickly ordered double Gibsons for himself and Walter and anything the twelve year old son wanted. Dinner was a tense affair with double Gibsons reordered in short intervals and we finally ushered an unstable Walter to the podium and an almost functional Heinecken to a nearby seat. Following an amazingly funny presentation I had to leave for home but Heinecken, Uelsmann and Walter spent the night drinking. The next day there were too many hangovers to count, but the Walter Chappell legend grew even more.

JKL: You and I first met when you were teaching photography at UCLA extension either in 1973 or 1974. I think that it was a class in alternative processes. You have continued to experiment with a variety of processes for decades. What are you currently working on and with what kind of process? Is there an alternative process that you haven’t experimented with that is still on your to-do list?

DC: Non-Silver: I got interested in non-silver through Robert Fichter and Todd Walker. Fichter was making cyanotypes in combination with drawing and rubber stamping. Todd was the master of alternative photographic media. His work usually focused on a single image which he manipulated through gum printing, collotype or silk screen printing. I asked both of them for advice and they offered everything including the type of paper, sizing, exposure control, suppliers, etc. I started with cyanotype, and soon became aware of everyday items that were transparent, such as product packaging and leaves. I also learned solvent transfer rubbing (transferring the ink of magazine images to paper). I combined silkscreen, transfers, cyanotype, Van Dyke Brown and anything that provided color to the piece. Most of the prints were made from enlarged 35mm negatives shot in snapshot mode, not serious photographic statements, but free and humorous.

Recently I’ve concentrated on solar photograms, that is gum print media exposed in sunlight featuring tools (hammer, wrenches, scissors) combined with leaves, small flat everyday items such as paper clips, straight pins, sewing thread, string, etc. The exhibition that I staged in March at DNJ Gallery expanded that idea into a mild form of performance/installation where I brought prepared gum print paper to the gallery, composed objects upon it and allowed it to expose beneath a skylight for one to five days. Gallery visitors experienced an image forming as they looked on, in a way completing the process.

JKL: You are a very prolific artist, with a very extensive resume, including teaching, curating, lecturing, workshops, etc. Has it ever been challenging to find the next idea?

DC: Next Idea: Yes. Every artist has a trunk-load of ideas. Finding the right combination of idea, media, scale, time and motivation is critical. I have rejected dozens of plans over the years. But one never knows which idea might prove to have merit unless one tries.

JKL: Photography into Sculpture exhibition: Could you talk about the original exhibition curated by Peter Bunnell at MOMA in 1970 and the recreation of the exhibition at Cherry and Martin Gallery in 2011.

DC: Yes. First let me say that I was very fortunate to be included in that exhibition. Heinecken recommended me to Peter Bunnell, MOMA Curator, who organized the show. My work barely qualified as it was frontal and measured 12”x12”x1”. The exhibition broke new ground and raised eyebrows in photographic circles, but I don’t think that it was noticed by the general art world.

Philip Martin of Cherry Martin Gallery made an amazing effort to recreate that exhibition and it was stunning. He researched museum records, reviews and interviewed nearly all of the living participants. He is the best expert on the project other than Peter. That show also traveled to Hauser & Wirth in New York and Le Consortium, Dijon, France.

JKL: In what ways did teaching inform your photographic practice and vice versa?

DC: Teaching the art of photography is an art in itself. One must be prepared, be open minded, be observant and strive to excel constantly. I tried to put myself in the shoes of students so that I could provide useful advice, I hope that that strategy worked. On the receiving end of that, I often got help in solving one of my own visual or conceptual problems through discussion, looking at negatives on a light table or commenting on prints coming out of the drier. Sometimes an idea would emerge based on a simple idea or image or joke.

J.K. Lavin is an artist whose photographic practice considers memory, self-portraiture and the measurement of time. Duration, as well as experimentation with randomness and chance is an important dimension of her work.

Lavin received a Master’s Degree of Art in Photography from California State University at Fullerton, California. She has also studied photography at The Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York and The Center of the Eye in Aspen, Colorado.

J. K. Lavin has had numerous solo exhibitions including a recent exhibition at The Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, MA. She was selected as a finalist for Klompching Gallery’s Fresh 2019. Her work has been included in group exhibitions at San Francisco Camerawork Gallery, San Francisco CA, Month of Photography Los Angeles, SE Center for Photography, Greenville SC, The Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins CO, Blue Sky Gallery, Portland OR, Building Bridges Art Exchange, Santa Monica CA and Fotofever Paris, France. Her photographs have been published in various on-line and print magazines including The Boston Globe, Diffusion, Los Angeles Magazine, Los Angeles Review of Books and What Will You Remember.

Lavin’s work is held in public collections.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026