Photographers on Photographers: Sara Macel on Maureen R. Drennan

©Maureen R. Drennan, Sault Ste Marie, Michigan, 2018, Man washes dust off his legs and feet, from Highway to the Sun

This month, we feature our annual August project, Photographers on Photographers, where visual artists interview colleagues they admire. Thank you to all who have participated for their time, energies and for efforts. Today we begin with Sara Macel’s interview with Maureen R. Drennan. – Aline Smithson and Brennan Booker

It was a humid night in early July when Maureen R. Drennan met me at Harefield Road, my favorite bar in Brooklyn, to talk shop for Lenscratch. Maureen and I have been friends for ten years now. We met in the hallways of SVA’s MFA Photography, Video, & Related Media department when she was a teaching assistant and I had just entered the program. Without fail, every time I see her our conversation ping-pongs from photo industry gossip to checking in on what each other is working on to deeply personal confessions about love and friendship. Maureen is one of my favorite artists and human beings. She has an uncanny ability to connect with people. And I mean really get down to it. Her photographs are “a secret about a secret,” as Diane Arbus famously put it. Over a bottle of rosé with our feet resting on the bottom rung of each other’s bar stools, we got down to it ourselves.

Maureen Drennan is a photographer born and based in New York City. Her work has been included in exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery in D.C., Tacoma Art Museum, Art Museum of South Texas, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Ackland Art Museum, Aperture Gallery, Mrs. Gallery, Colorado Photographic Arts Center, Transmitter Gallery, Centotto Gallery, Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design, Silver Eye Center for Photography, Houston Center for Photography, Pingyao Photography Festival in China, and Newspace Center for Photography. Her images have been featured in The New Yorker, The New York Times, California Sunday Magazine, Photograph Magazine, Huffington Post, Art 21 Magazine, American Photo, UK Telegraph, Refinery 29, Narratively, Newest York, and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. She teaches at LaGuardia Community College in Queens, New York.

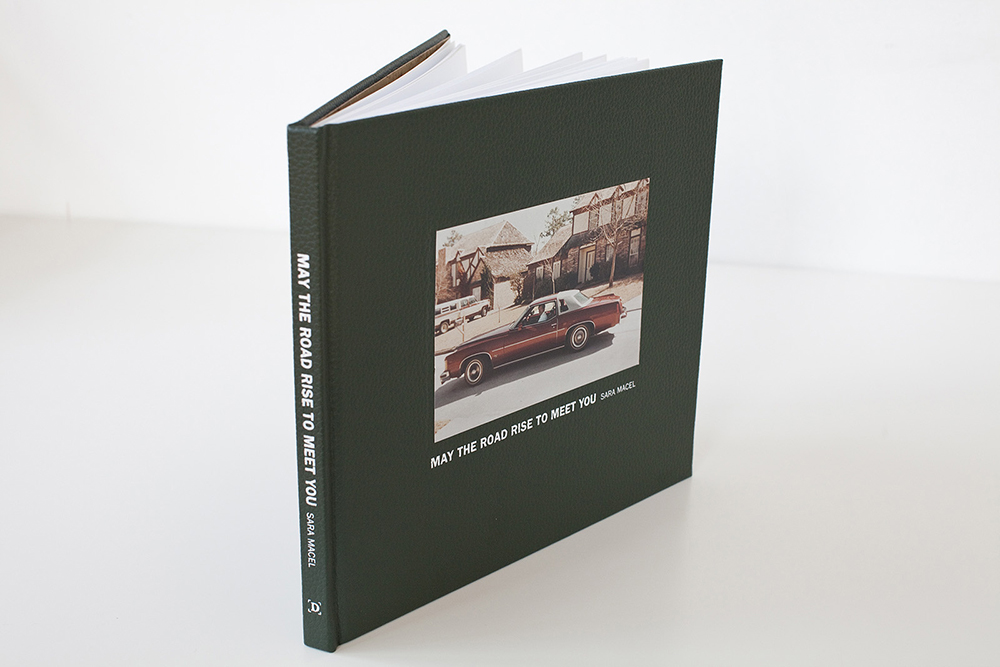

Sara Macel (b. 1981 Houston, TX) is an artist and photographer based in Queens, NY. She received her MFA in Photography, Video & Related Media from the School of Visual Arts and earned her BFA in Photography + Imaging from NYU. Her photographic work is narratively-based and often deals with themes of the archive, family, memory, place and time. Her work has been internationally exhibited and is in various private collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Cleveland Museum of Art, Harry Ransom Center, and the Center for Photography at Woodstock. Sara was named one of PDN’s 30 Photographers to Watch in 2015. She is a recipient of the Individual Photographer’s Fellowship Grant from the Aaron Siskind Foundation and was recently an artist-in-residence at Light Work in Syracuse, NY. Her first monograph, May the Road Rise to Meet You (Daylight Books), was named one of PDN’s best photo books of the year. A traveling exhibition of that work was shown in solo shows around the country. Her new series What Did the Deep Sea Say received a 3rd place award at CENTER Santa Fe. Sara is a full-time professor and photography program coordinator at SUNY Rockland Community College. Her work has been featured in National Geographic, The New Yorker. Huffington Post, Wired Magazine, Fraction Magazine, and Lenscratch among others.

Sara Macel: Maureen, this is such a pleasure. As you know, I’ve been a huge fan of your work for years and I love seeing what subject matter you dive into next. From your ice fishermen to a reclusive marijuana farmer to transgender teenagers to your own husband’s mental health journey, you photograph people and small communities that are a step removed from society either geographically or emotionally (or in some cases both.) I see your work as constantly redefining what it means to “march to the beat of your own drum.” Does that description of your work ring true to you? How do you define the connective tissue of your bodies of work?

Sara Macel: Maureen, this is such a pleasure. As you know, I’ve been a huge fan of your work for years and I love seeing what subject matter you dive into next. From your ice fishermen to a reclusive marijuana farmer to transgender teenagers to your own husband’s mental health journey, you photograph people and small communities that are a step removed from society either geographically or emotionally (or in some cases both.) I see your work as constantly redefining what it means to “march to the beat of your own drum.” Does that description of your work ring true to you? How do you define the connective tissue of your bodies of work?

Maurenn Drennan: Hi there Sara, I am huge fan of your work as well and I’m thrilled you wanted to interview me, thank you! I am consistently attracted to places and people on the edges, where the land and community are fragile or in transition. I draw inspiration from people I engage with and photograph. There is definitely an intuitive attraction and often its people’s vulnerability as well as resilience that resonates with me.

Bridging across all my projects there is often a simultaneous fierce independence and fragility in the people I photograph. It’s like what William Faulkner said, “the only story worth telling is the human heart in conflict with itself.”

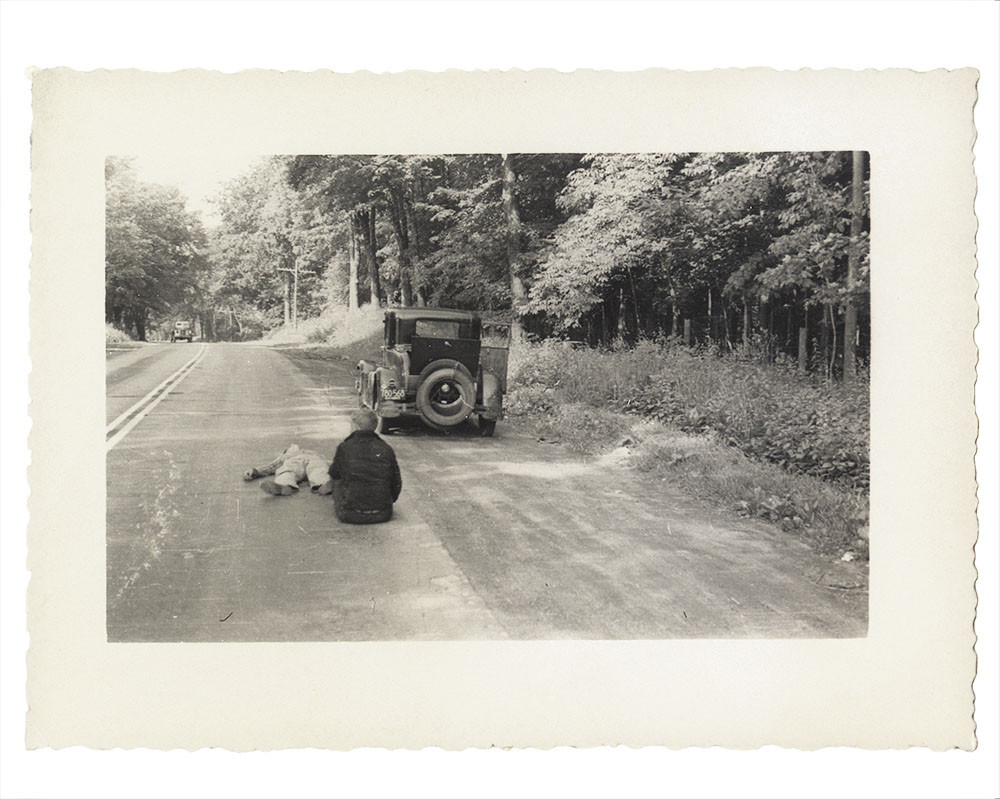

SM: In Highway to the Sun, you took a personal archive in the form of your stepfather’s snapshots and travelogue of the 1951 road trip he made as a young man with three friends, and began making your own medium-format color contemporary photographs while traveling that interweave with his black and white images. I often work with archival materials from my family as a launching off point for my work as well. May the Road Rise to Meet You chronicled my father’s life on the road as a traveling salesman and all started with a snapshot of him as a young dad leaving home in the company car. And it was the discovery of a suitcase of old negatives belonging to my grandmother that launched What Did the Deep Sea Say and led me to Hollywood, Florida to retrace her steps. Why did you want to make this work? What challenges did you encounter in the making of the color images? Were they inspired by specific black and white images or did you divorce yourself from that restriction of call-and-response?

MD: I’ve known about my stepfather’s trip for years, it’s one of those family stories you hear over and over to the point of myth. A few years ago I thought- wow, this is such a great story- how can I add to it photographically? How can I insert myself into their epic road trip?

Utilizing their photographs and log, I imagined these young travelers moving toward an endlessly bright future and I wanted my photographs to reflect that. Their descriptions and photographs of constant car trouble, sleep-ing alongside the road, eating minimally to save money, cutting each other’s hair, washing in rivers, and many of the people they encountered are so visually rich. There is also an intimacy and tenderness between the young travelers that I am intrigued with tapping into. What did male friendship look like then? How can I, as a woman, understand and convey the relationships between these men who were living in 1951?

Initially, my photographs were too illustrative, too much of a call-and-response to their images and words, so I changed my approach. Instead, I envisioned myself on a parallel journey with an uncertain ending. I’m continuing to work in this way and it’s liberating. I’m thinking about mood and atmosphere and less about specific subject matter. The color photographs I created are not literal representations of characters or locations in the travel log; I am more interested in blending the past and present. They depict my understanding of the trip as a journey of exploration and invention as well as engaging with the myth of the American western road trip.

©Maureen R. Drennan, West Yellowstone, Montana, 1951, Put lies in road trying to do calisthenics, from Highway to the Sun

©Maureen R. Drennan, Spring Water, Oregon, 2013, Man with broken leg shields eyes from sun, from Highway to the Sun

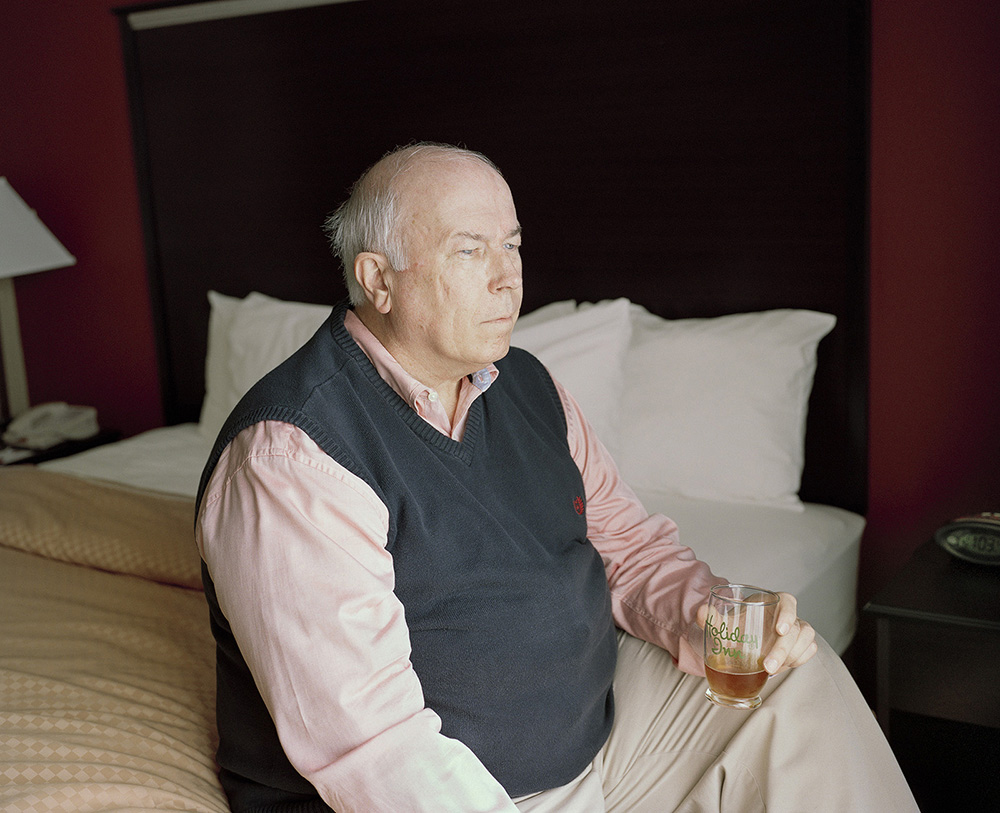

SM: Your first self-published book is called The Sea That Surrounds Us and it’s portraits of your husband Paul paired with foggy, gorgeous ocean landscapes of Block Island. This series documents a difficult period in your marriage and Paul’s struggle with depression. In another interview, you spoke of this work saying, “Good art often doesn’t come from a comfortable place.” I find that if I’m pushing myself to con-front an uncomfortable emotion in my work, I’m usually on to something. But it must have been difficult to know where that line was or how much to embrace that discomfort when you’re photographing your own husband in that state. Paul is a crazy talented painter in his own right. Did the fact that you’re both artists create a unique form of communication to help you both say the things you struggled to verbalize? Do you still photograph Paul now that this period in your lives has passed and healed?

MD: I love that idea of “a unique form of communication”. It absolutely helps that we are both artists. I think he inherently recognized that it was important for me to try and understand what was happening with him. The hardest part was starting the project as he was in this incredibly fragile place, and I didn’t want to isolate him further. But once I began making images of him, it felt comfortable and became part of what we did together. Making images during that time period was restorative and intimate. Through this project I recognized how inti-macy and fragility can be painful but rewarding. Vulnerability is what makes us human, what makes us beautiful.

I do still photograph him and we collaborate on projects. We just recently worked on a piece together for an exhibit called “Forced Collaboration, Couples Edition” put together by Jacob Rhodes from Field Projects which was lots of fun.

©Maureen R. Drennan, Christmas, Montreal , 2010, Paul brushes his teeth in a hotel room in Montreal, from the sea that surrounds us

SM: What did you learn in making this project into a book?

MD: Paul and I worked on the edit and design together so it was a continuation of negotiation and collaboration that was helpful and really fun. When I initially made this project about him, it was for us. I had no idea whether people would respond to it. I was surprised and blown away at the positive response and how many people reached out to me to talk about depression and how this project had helped them. I feel enormously fortunate to still get emails from strangers around the world and the 1st edition of the book has sold out and there are very few of the 2nd editions left.

©Maureen R. Drennan, Did your dream drift from mine, 2011, Paul stands in his mothers yard in Wisconsin, from the sea that surrounds us

SM: You recently made a completely gorgeous book maquette for Meet Me in the Green Glen, or as I like to call it “your weed project.” You worked with Ben Salesse who designed and helped edit Rose Marie Cromwell’s critically praised book El Libro Supremo de la Suerte. What was it like working with an editor and a designer? How did making this book differ from your first book?

©Maureen R. Drennan, Garden, 2008, Marijuana plants nearing harvest season in the fall , from Meet Me in the Green Glen

MD: Thank you! I’m so happy you like it.

Ben is an incredible designer, and he and Rose created a stunning book. As you know from your own beautiful book, May the Road Rise to Meet You, choosing which images to include and then sequencing them to tell the story you want is a puzzle. Each time you change the edit the meaning changes, there is this constant reworking. Context and sequence is paramount and it is hard to get it right.

Ben helped me immeasurably with creating a mood and establishing a rhythm for the viewer but also leaving things open for interpretation and possibility. He has a fresher way of seeing the project than I do and he organized and created it in a way I wouldn’t have thought of. I am so happy with it and feel enormously grateful and lucky to have worked with him.

©Maureen R. Drennan, King of the Mountain, 2009, Ben climbing a rock near his childhood home in California, from Meet Me in The Green Glen

SM: Lastly, our respective projects Highway to the Sun and What Did the Deep Sea Say will be on view this fall in the Center for Photography at Woodstock’s upcoming “Photography Now 2019: The Searchers” exhibition guest curated by Marvin Heiferman and Maurice Berger. Maureen, what are you searching for?

MD: Ha! Such an existential question! I am so excited for that show, it will be great.

I am drawn to connect with people in an intimate and serendipitous way and hear their stories. The ephemeral nature of our connection, for me, heightens the experience. On July 4th, I met a guy who drove me around Broad Channel, Queens on his moped. It was a beautiful summer night and we were chasing the various fireworks being set off by locals so I could photograph them. While we were riding he told me about his alcoholic father who died a few weeks ago and his own struggle with drug addiction. The poetry of chasing something fleeting while riding on the back of this stranger’s moped while he opened up to me was pretty amazing. I feel very lucky to have these experiences.

Statements for featured work:

Highway to the Sun

“A journey is a person in itself, no two are alike…We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us.”- John Steinbeck

In 1951, my stepfather and his friends left New Hampshire and set out for Alaska in two model A Fords. They were heading to Alaska in search of work, thus their trip was not merely a voyage of discovery.

They made the 5133-mile trip in two weeks despite rain, muddy roads, and constant car trouble. The young men took photographs and kept a detailed log describing sleeping alongside the road, eating minimally to save money, cutting each other’s hair, washing in rivers, and many of the people they encountered. There is an intimacy and tenderness between the young travelers. This project includes their images and mine; I’m interested in blending past and present and engaging with the myth of the American western road trip. The images depict my understanding of the trip as a journey of exploration and invention.

Photography can be suggestive and illusory. Although called a “mirror with a memory” from its inception in 1839, it has the ability to revise our memories. I have been imagining their trip and making my own images based on my fiction and their stories. I have wondered about the people they encountered and where they might be now. Photographs can be like a burst of memory. Not necessarily accurate, but fleeting and vivid.

the sea that surrounds us

The title of this photographic series, the sea that surrounds us, comes from a love poem by Pablo Neruda and suggests the isolation and protection one can simultaneously experience within a relationship. In trying to comprehend my husband’s vulnerability due to a severe depression, I made images of him and a landscape familiar to me, Block Island, RI.

When I was seven years old and my parents separated, I lived there for a year with my father. It was a lonely time, the windblown landscape on Block Island is beautiful but deserted and watching the dissolution of my parent’s marriage was sad to see.

When my own marriage was in turmoil, I returned there to photograph. The landscapes work both as self-portraits and as ruminations on isolation and distance. I have often photographed my husband, but this felt different. I was watching him more carefully, trying to understand him. I felt untethered and helpless observing him and trying to comprehend his inner turmoil. The intimacy of making the photographs together during a challenging time was restorative. Where words failed us, the pictures filled in the blanks.

Meet Me in the Green Glen

Meet Me in the Green Glen is an intimate photographic look at a reclusive marijuana grower in California. He was an isolated man whose environment was both ominous and verdant. We met several years ago and through this project became close. I photographed him for nine years while the laws and stigma around marijuana cultivation changed radically in California. This farmer, Ben, was growing marijuana for years before it was legal and had to carefully navigate within the legal system to grow, maintain, sell, and transport his product. Although marijuana is legal to grow and use within guidelines, there are situations in which it is still illegal. It continues to be a murky world.

Every year Ben, hired young men to help with the harvest season. They worked for about one month and then he was alone again on his farm with his animals. A tangible melancholy pervades Ben’s life: his guard dogs, geese, and the pot plants he tends are his only steady companions. He was deeply connected to his environment and insulated from the clamor of the outside world.

American Literature, in particular Flannery O’ Connor and Annie Proulx, have had a significant influence on my imagery. In describing the landscape both writers evoke a psychological and emotional sense of place in which the environment becomes a character unto itself and amplifies the aloneness of the characters. I am drawn to narratives, photographic, literary, cinematic, or documentary- in which characters are crafted out of place, or in which places actively become the characters themselves.

Statements for featured work:

May the Road Rise to Meet You

For the past forty years, my father has traveled around America as a telephone pole salesman.

May the Road Rise to Meet You is a pseudo-documentary of his professional life and a collaboration between father and daughter to create a visual document of the life he has led separate from our shared family experience. In popular mythology, few professions are as emblematic of America as the traveling salesman. As the Internet and outsourcing make this once ubiquitous occupation obsolete, May the Road Rise to Meet You explores the life of a businessman alone on the road. On a larger scale, this project explores the changing nature of “the road” in American culture and in the history of photography.

We were traveling north on I-45 through Texas when I asked my dad what it was like dealing with customers. He told me: “There’s that old saying that you don’t know someone until you walk a few miles in their moccasins.” It was in that spirit that I put myself in my father’s size 10 boots and invite you, the viewer, to do the same. What I found in following this enormously elusive male figure around the country is that I can never fully know my father as a man or what it is like to be a man alone on the road. Many of these photographs are my fantasy of what his life on the road looked like over the years. In the same way that a family photo album functions to present an idealized version of a family’s history, these photographs tell the story of how we both want his life on the road to be remembered.

What Did the Deep Sea Say

We all have secret desires and memories that we keep in the quiet of our hearts. Some of us take those secrets to our graves, but the photographs we leave behind can betray our trust and hint at the private lives we led. What Did the Deep Sea Say is a photographic narrative about three generations of women in my family who all came to the same beach to briefly escape their lives. When I uncovered a long-forgotten suitcase of negatives that belonged to my deceased grandmother, the photographs she hid told the story of a young woman who left the Northeast during WWII to live a carefree life in balmy Hollywood, Florida. With only her photos as my guide, I traveled to Florida to retrace her steps and photograph the spaces she inhabited. With this seaside town as the backdrop, I also photographed my mother and myself as we both formed our own unique connections to this place. “WDTDSS” utilizes and plays with the role archives and photo albums play in crafting our subjective memories and family histories. By interweaving my grandmother’s black and white images with my own color photographs, I am deliberately mixing fact and fiction, as well as past and present. What Did the Deep Sea Say is an on-going series about the unknowable ocean that swells within us all and the uncovering of its familiar tides within my own maternal lineage.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026