Greg Kahn: Havana Youth

“These photos explore the emerging sense of individuality in a society that was historically focused on collectivism. It shows how Cuban youth are reaching out to their US and European counterparts through cultural world trends.”

Sometime ago I attended a lecture by Greg Kahn at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles. His artist’s talk was one of many about Cuba during the Annenberg exhibition, Cuba Is. That evening I came away with a whole new perspective on the next generation of Cuban Youth. I’ve always thought of Cuba as a culture of waiting, but Greg shifted the way I see the future of the island. His project and new book by Yoffy Press, Havana Youth, “explores Cubans born after 1989, who have only known a time after the USSR dissolved and left the Caribbean nation with few resources and a growth-crippling, US-led economic embargo. Those kids, born during what is called “The Special Period”, are now in their twenties and developing a sense of individuality in a society that was historically focused on collectivism. This is their cultural counter-revolution, and they are redefining what it means to be Cuban.”

One of the most fascinating aspects of Greg’s examination of youth culture is recognizing that technology leap frogged from ancient land lines to iPhone technology in this generation, opening up the world and providing global inspiration that affects all aspects of Cuban youth culture.

©Greg Kahn, Jerry Rivera, 24, lights the oven to cook lunch at his apartment in Playa, a suburb on the Westside of Havana. Despite a growing embrace of new technology with smartphones and televisions, Cuba’s infrastructure remains fraught with power outages and staple foods being hard to find, from Havana Youth

Greg Kahn (b. 1981) is a Washington, DC – based American documentary fine art photographer. Kahn grew up in a small coastal town in Rhode Island, and attended The George Washington University in Washington D.C. In August of 2012, Kahn co-founded GRAIN Images with his wife Lexey, and colleague Tristan Spinski.

Kahn’s work concentrates on issues that shape personal and cultural identity. His Pulitzer Prize nominated project, “It’s Not a House, It’s a Home,” explores how the foreclosure crisis in Florida defined a new class of homelessness. His recent project in Cuba considers how governance molds individuality. And in Kahn’s ongoing project 3 Millimeters, the quiet depletion of land is the catalyst for the evolution of the inhabitants’ identity.

Clients include: AARP, The Atlantic Magazine, Audubon Society Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek, Fortune, National Geographic Traveler, New York Magazine, New York Times Magazine, NIKE, Smithsonian Magazine, Washington Post Magazine, Washingtonian Magazine, Wired

Havana Youth

When Fidel Castro overthrew the Cuban government in 1959, it signaled a move to emphasize the collective state over the individual. Businesses were nationalized, private property was seized by the government and converted into military facilities, schools and other infrastructure. Castro’s philosophy was to educate students to be an asset in society, not for uniqueness. The revolution ushered in resentment toward the bourgeois, the United States, and their perceived luxuries.

Cubans born after 1989 have only known a time after the USSR dissolved and left the Caribbean nation with little resources and a powerful, growth-crippling, US-led economic embargo. With 80 percent of their imports and exports eliminated by the Cold War, Cubans lived on scarce food and a crumbling infrastructure. This wasn’t the government they were promised. Those kids, born during what is called “The Special Period”, are now in their teens and twenties.

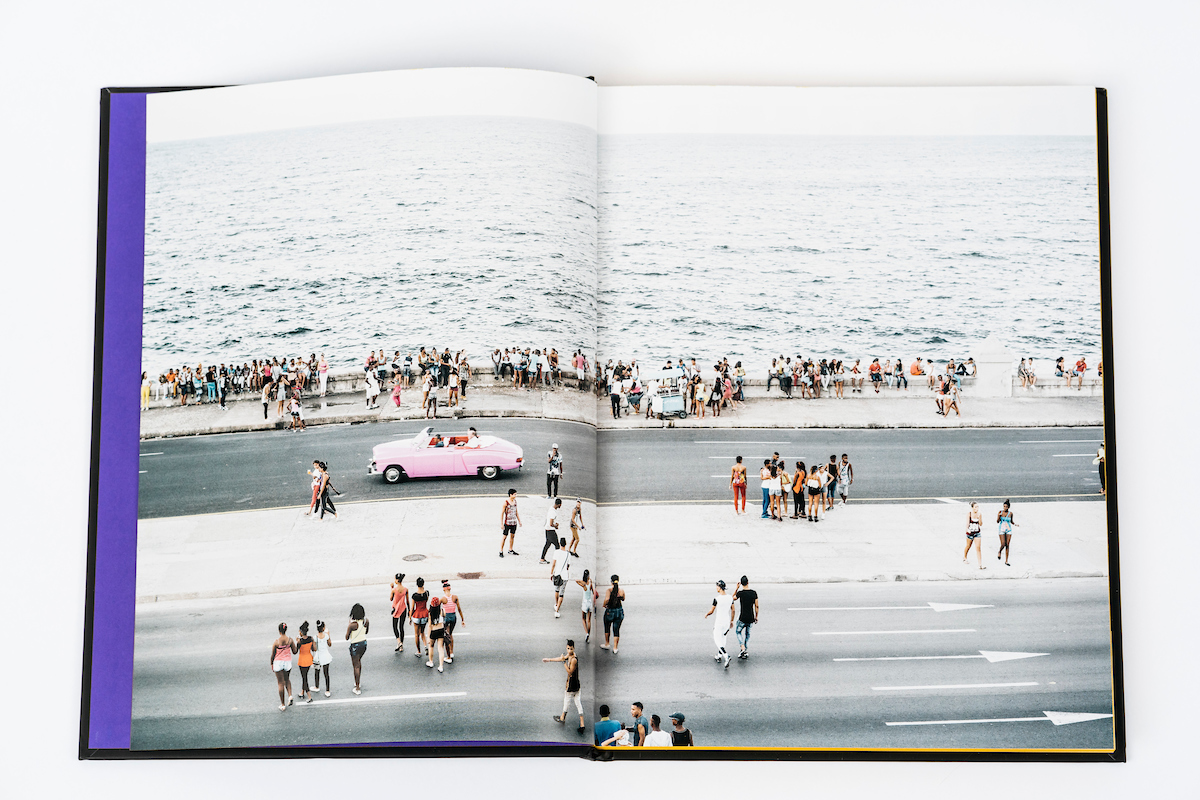

Soon after Fidel ceded power to his brother Raul in 2008, Havana’s youth began experiencing influences from the whole world. Now they are focused on the present, not burdened by the past. They are grasping whatever they have access to in a collective effort to keep pace with international trends and establish their own identity. The once evolutionary process for cultural identity has jolted like the slip-strike of a tectonic plate — from landline phones to a retina-screen iPhone. No cordless landlines, no pagers, no car phones, flip-phones, or any of the other technological steps that have guided cultures from rotary dials to Siri. Their clothing reflects their desires and carries an underlying meaning. Miguel Leyva, a fashion blogger in Havana explained the cultural significance. “Clothes have a strong connotation here, like a journalist writing an article against the government,” Leyva said. “It means to be free.”

These photos explore the emerging sense of individuality in a society that was historically focused on collectivism. It shows how Cuban youth are reaching out to their US and European counterparts through cultural world trends. These aren’t residents trying to flee the country and cut ties. There is apathy and frustration over the system, but there is also pride. Although the Cuban youth identity is evolving rapidly, the choices they are making are authentic. This is their counter-revolution. And they are redefining what it means to be Cuban.

©Greg Kahn, Cuban teens have a smoke during a pool party at Miramar Chateau, a hotel near the beach in Havana,from Havana Youth

©Greg Kahn, Miguel Leyva, 22, a fashion blogger in Havana. Leyva says that the Cuban youth no longer look at magazines and see items as unattainable, but instead see styles they could eventually have. Leyva also talked about clothing being a type of protest, “Clothes have a strong connotation here, like a journalist writing an article against the government,” Leyva said. “It means to be free.” from Havana Youth

©Greg Kahn, Yosmel Azcuy, 28, a professional break dancer, holds the hand of his wife, Guirmaray Silva, 29, as they wait for the electricity to come back on in their apartment in Havana. These power outages can occur weekly because of a crumbling infastructure from Havana Youth

©Greg Kahn, Anna Marie Mesa, 16, listens to music on her smartphone in Centro Havana. Technology is leapfrogging the infastructure in Cuba where citizens went from landlines to smartphones in a matter of months. Cubans born after 1989 have only known a time after the USSR dissolved and left the Caribbean nation with little resources and a powerful, growth-crippling, US-led economic embargo, from Havana aYouth

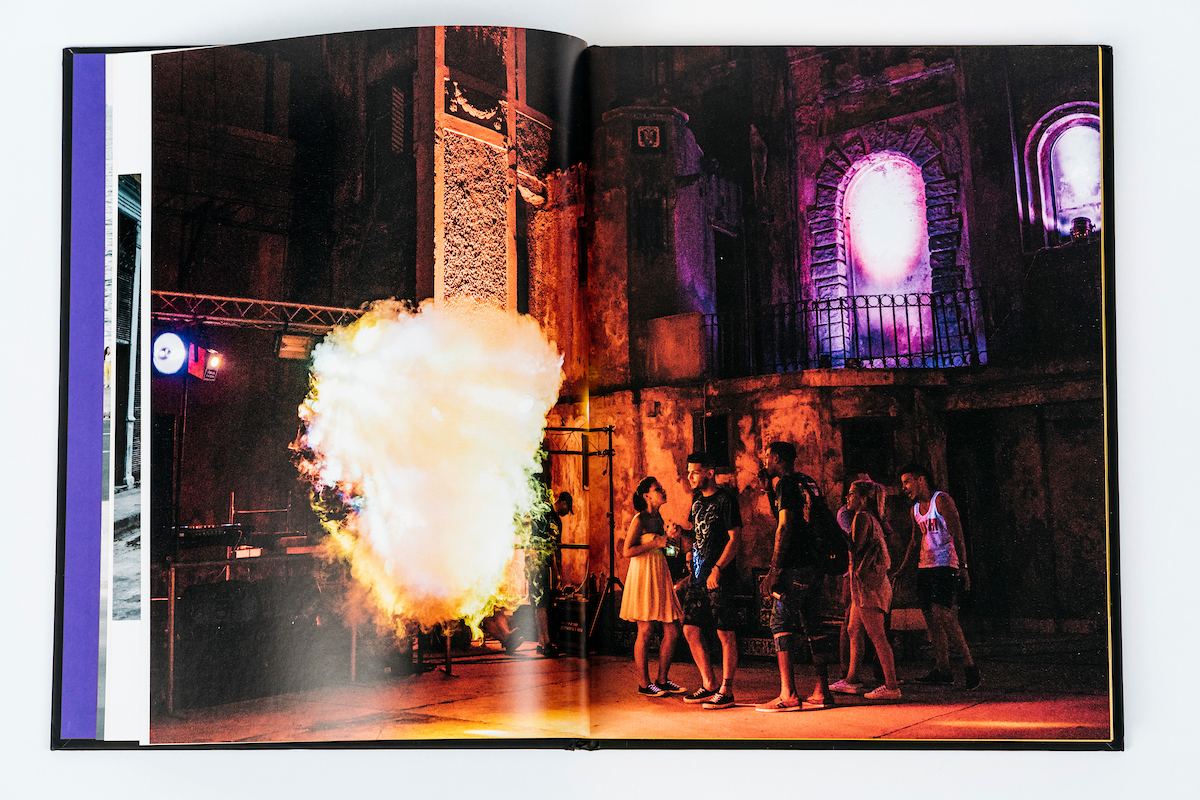

©Greg Kahn, Break dancers warm up for an exhibition dance battle in front of Catedral Del Picadillo, a multipurpose center in the Havana neighborhood of Jaimanitas. Break-dancing in Cuba goes back to the early 80s, the same time it rose to prominence in the United States. But in the late 1980s through early 2000s, the movement all but disappeared — the result of Cuba being disconnected from international culture and media. Now break dancing is back and gaining momentum with the new music and style emerging in Havana. Red Bull, an energy drink company based in Europe, has even brought several Cuban “breakers” on tour through Europe. And now, with wifi connections across Havana, YouTube videos and movies of dance battles are being watched and downloaded regularly, from Havana Youth

©Greg Kahn, Pompi, 26, a self taught tailor sews together fabric for his dance company. Pompi has family that lives in Germany and his wife’s family in Miami, but he chooses to stay in Cuba. He wants to be involved in the conversation on the future of his island nation, from Havana Youth

©Greg Kahn, Rachel Gonzalez, 25, one of the members of the Havana Queens dance company at practice, from Havana Youth

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026