Dana Fritz: Views Removed

Views Removed by Dana Fritz was selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was pleased to interview Dana to gain further insight into this body of work.

Dana Fritz investigates the ways we shape and represent the natural world in cultivated and constructed landscapes. She holds a BFA from Kansas City Art Institute and an MFA from Arizona State University. Her honors include an Arizona Commission on the Arts Fellowship, a Rotary Foundation Group Study Exchange to Japan, a Society for Photographic Education Imagemaker Award, and Juror’s Awards in national exhibitions. Fritz’s work has been exhibited in over 80 venues including the Phoenix Art Museum, Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts, the Griffin Museum of Photography, and the Sheldon Museum of Art in the U.S. International venues include Museum Belvédère in The Netherlands, Château de Villandry in France, Xi’an Jiaotong University Art Museum in China, and Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, Place M, and Nihonbashi Institute of Contemporary Arts in Japan. Fritz’s work has been published in numerous exhibition catalogs including IN VIVO: the nature of nature (Noorderlicht House of Photography,) Encounters: Photography from the Sheldon Museum of Art, and Grasslands/Separating Species, and was featured in print magazines Harper’s, Orion, Border Crossings, Studio, and Photography Quarterly. Her portfolios Garden Views, Terraria Gigantica, and Views Removed were selected for the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s Midwest Photographers Project from 2004-06, 2008-12, and 2015-21 respectively. Her work is held in several collections including the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Pennsylvania; Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona; Weeks Gallery Global Collection of Photography at Jamestown Community College, New York; the Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art; and Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Fritz has been awarded artist residencies at locations known for their significant cultural histories and gardens or unique landscapes: Villa Montalvo in Saratoga, California; Château de Rochefort-en-Terre in Brittany, France; Biosphere 2 in Oracle, Arizona; PLAYA in Summer Lake, Oregon; Cedar Point Biological Station in Ogallala, Nebraska, and Brush Creek Foundation for the Arts in Saratoga, Wyoming. University of New Mexico Press published her monograph, Terraria Gigantica: The World under Glass, in 2017. She is currently Hixson-Lied Professor of Art in the School of Art, Art History & Design at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Prints from Views Removed can be seen in Representing the West: A New Frontier at Sangre de Christo Art Center, Pueblo, Colorado Feb 7 – May 10, 2020 and the books have recently been acquired by the following public collections: University of North Texas, University Libraries Special Collections; Colorado University Boulder, Special Collections, Archives, and Preservation; Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Hirsch Library.

Views Removed

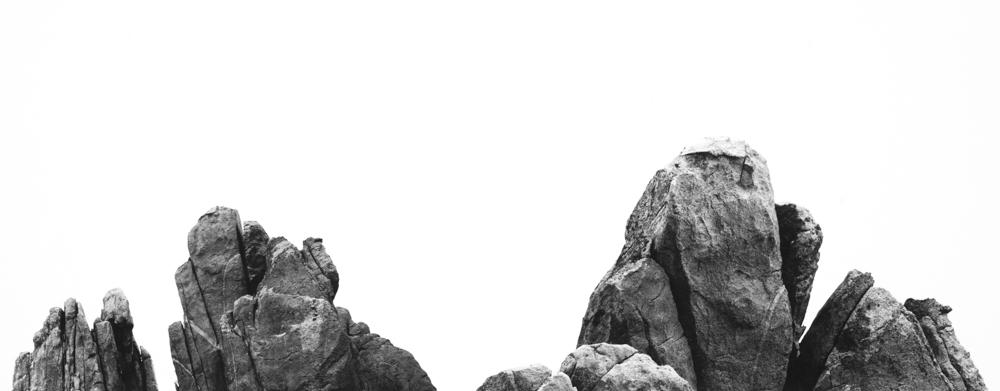

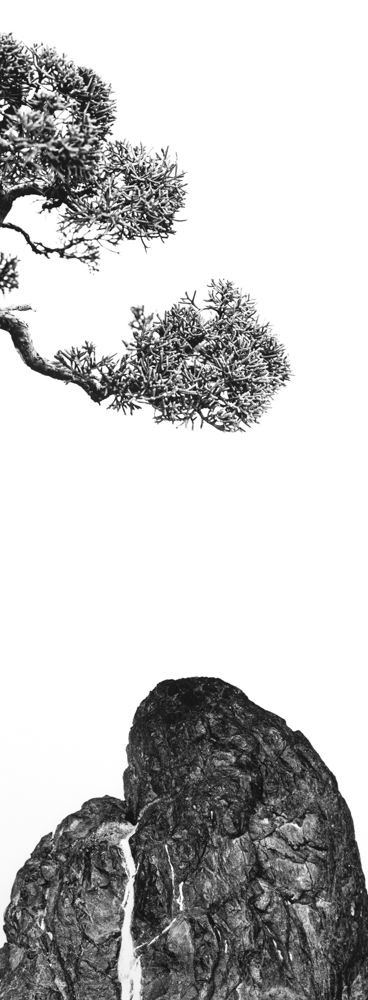

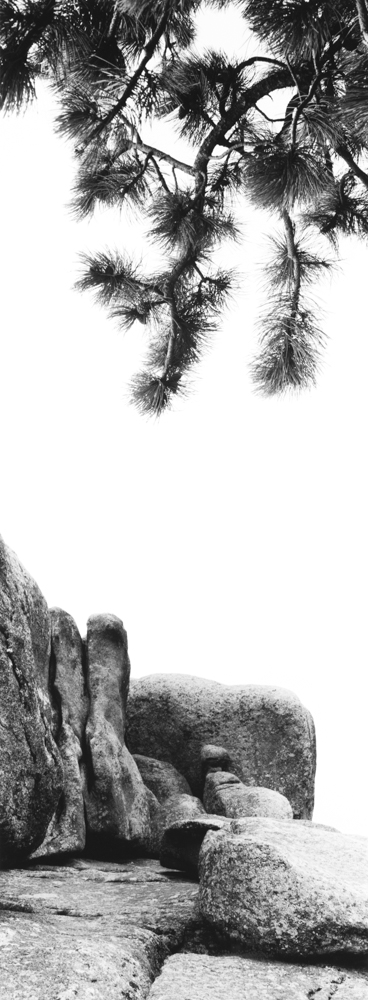

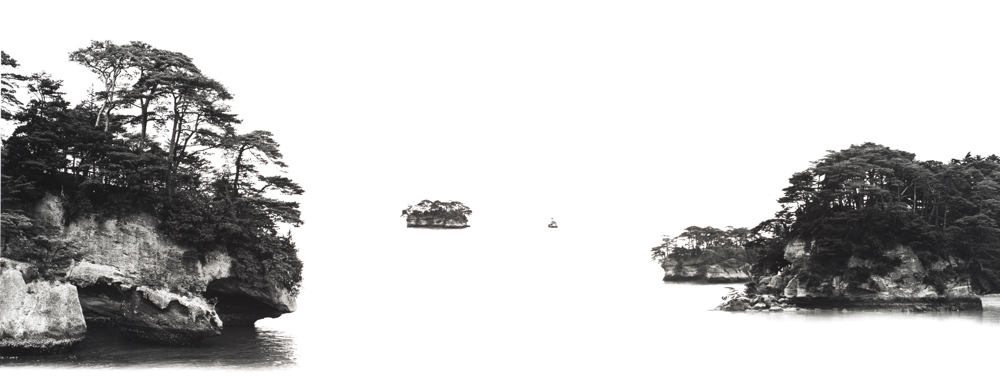

The photographs in Views Removed render trees, stones and other natural materials in ways that their scale and perspective become ambiguous, combining more than one negative to create a “landscape view” that exists only in the final print. The composition and contrast in the resulting gelatin silver prints emulate the white paper background and equivocal space in ink painting traditions that are free from the technical constraints of photography. The photographs are inspired by questions about Eastern and Western pictorial space, landscape as construct, and the inherent tension between the real and ideal.

The Views Removed series includes small editions of gelatin silver prints on 20×8 inch or 12×20 inch paper.

Daniel George: You have been making work dealing with constructed landscapes for a while now, including those of gardens, zoos, and biospheres. When did you become interested in fabricating your own landscapes?

Dana Fritz: I have always recognized the work of the gardeners, designers, sculptors, landscape architects, etc. that makes formal gardens and vivaria possible, but I started wondering about the origins of their ideas about landscape. Were they informed by two-dimensional views rendered in paintings? How do these paintings make cultural ideas about nature visible?

DG: You write that questions about Eastern and Western pictorial space partially inspired this project. What were some of these questions? And how do you feel the work responds to these queries?

DF: After teaching a Japanese Visual Culture class in Japan for ten years, I had begun to think a lot about the differences in Eastern and Western landscape painting. I was especially interested in painting because of its long tradition but also because of the inherent compression of space, a feature it has in common with gardens and vivaria. Ink painting traditions from China and Japan have a number of characteristics that fascinate me. Unlike western painting where the use of light and shade models mass and form and linear perspective creates illusionistic depth, paintings of the east have a distinct spatial flatness where the foreground is in the bottom of the image and background is generally up in the top. The spatial zones are frequently separated by clouds or mist that is often rendered through absence of ink where the paper or silk is visible.

DG: I am intrigued by the negative space that you have allotted in each image, and how my imagination is allowed to fill in the gaps based on my personal experiences outdoors. Could you describe your intentions in providing so much open space?

DF: Negative space is a common feature in Japanese art of all kinds and I had been drawn to it more and more because of my natural tendency to make multilayered compositions full of information like the ones in Terraria Gigantica. In short, I needed some space in my mind and in my work. A lot of the negatives for Views Removed were made in a year than included both teaching my summer class in Japan and an extended stay there during my faculty dvelopment leave. Your observation about the possibilities of negative space for a viewer is on point. Kenya Hara’s book White is especially useful in understanding how emptiness functions. He writes, “emptiness does not merely imply simplicity of form… Rather, it provides a space within which our imaginations can run free, vastly enriching our powers of perception and our mutual comprehension. Emptiness is this potential.” I have lived most of my life on the eastern edge of the Great Plains looking west. This sense of open space seems to unite the ink paintings with both the actual spare and sparsely populated landscape and the problematic but persistent ideas about freedom, possibility, and solitude often associated with the American west. In both cases, the openness and negative space leave room for contemplation. (Views Removed includes photographs made in Japan as well as the American West.)

DG: These are printed in the darkroom, and you have also created lovely accordion and handscroll volumes. How important is materiality in the final presentation of this work?

DF: There are multiple types of materiality in the prints and artist books, depending on how this work is experienced. However, all of it is lost when they are viewed on a screen.

When I started the series, I was interested in the challenge of printing multiple negatives on a single sheet of paper in the darkroom because I thought it would be a lot more engaging than doing it digitally. I was also interested in a dialog between ink painting and photography. While my prints evoke ink paintings when viewed, they don’t actually resemble them because they contain so many photographic qualities such as the glossy gelatin silver paper, visible depth of focus, grain, etc. When exhibited, the full-size prints are matted and framed in a traditionally photographic way to emphasize that.

As I was making the last photographs for the series, I wanted to find a way to both collect the images into a portable format and to mark the project’s completion. Having become familiar with screens, accordion books, and handscrolls from the far east, I thought these forms may be a good match for the small edition of artist books I wanted to produce. I was particularly interested in how the images and text in a handscroll are generally only viewed in sections that are the based on a comfortable distance between the hands of the viewer unrolling it. Because most of it is not visible, there is a sense of mystery and possibility about what is just out of view and even a feeling that the landscape inside could extend almost infinitely along the horizon. I certainly made this connection when I was photographing for the series in Oregon and Wyoming. Squinting at the rock formations rising out of the wide basins and playas, I saw a relationship to the horizontal imagined landscapes in handscroll ink paintings. The Views Removed handscroll encourages the viewer to choose the landscape view at arm’s length, even combining multiple images into new landscapes, in a way that mirrors how the analog composite photographs were produced. The vertical images from the series are collected into an accordion book that can be viewed as facing pages or completely unfolded like a larger folding screen.

DG: These images bring to mind the picturesque tours of late 1700’s in Britain, where individuals were guided to the countryside to admire pre-selected, quintessential views of the land. In a way, you are doing the same thing for the viewer by combining landscape elements to stimulate a particular interpretation. Tell me more about the attention that you are paying the ideal, and why you feel it is important to address these themes.

DF: Indeed, this idea of pre-selected ideal natural or constructed views transcends time and place. We also see it in Japanese gardens and in National Park viewpoints. While my previous projects were more straightforward in how I photographed idealized, human shaped landscapes, in Views Removed, I am the one shaping the landscapes based on my imagination of an impossible ideal. It is my hope that viewers consider questions about our relationship to the natural world, landscape views in art, how we construct ideas of landscape, and how we shape the land itself- themes that thread throughout all of my work.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026