Remembering Robert Herman 1955-2020

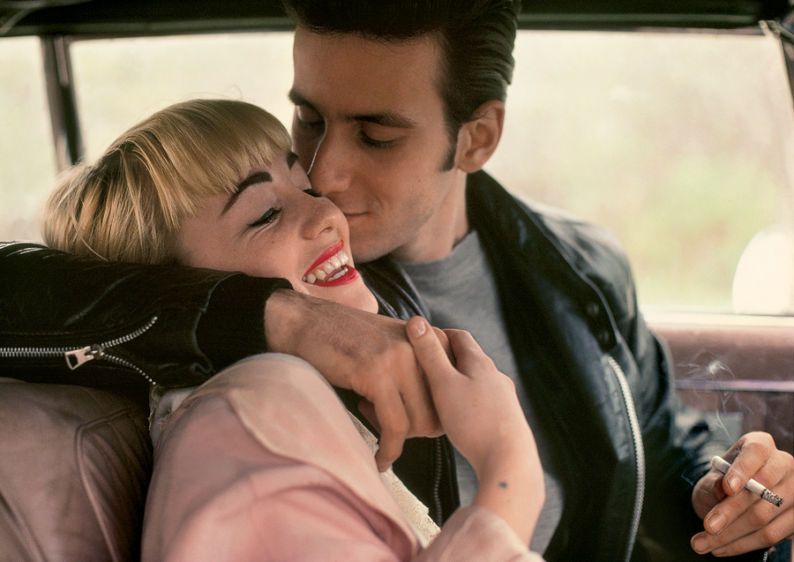

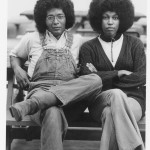

©Robert Herman

I have shared the work of Brooklyn born photographer Robert Herman several times over the years, so I was distraught to learn that this wonderful artist recently took his own life. I remember him sharing that as a young man, Robert began working as an usher at a movie theater owned by his parents. The exposure to a wide range of films during his formative years provided him with a unique vision: “Working for my father allowed me to view the same movie repeatedly,” he recalled, “until the story line began to recede and the images became independent of the narrative.” I love that concept of considering photographs. Today, his friend Reuben Radding shares memories of Robert and we share some Robert’s work and thoughts. – Aline Smithson

The New York photo community is reeling this week from the sudden loss of our friend, Robert Herman, who died by suicide on Friday, March 20th. He was 64 years old. I last saw Robert ten days before his passing, in the TriBeCa neighborhood he called home. We spent between 30 minutes and an hour on the sidewalk discussing some of our usual subjects: the difficulties and dilemmas of getting by as artists, the ways New York has and hasn’t changed since our heyday in the 80’s, and the love we both had for the medium’s endless magical possibilities. Robert was a truly gifted and ambitious man, determined to have his work respected, but he was also a stalwart supporter of others, always ready to offer advice on self-publishing and the ins and outs of the photo world. I saw him at the vast majority of photo show openings I ever went to in the city, and he was always friendly and encouraging to all. To be sure, Robert could be quite intense, and that made getting close to him difficult at times. In our final conversation I remember feeling like we had finally become good friends, and that he trusted me. He had been spending a lot of time in Italy these past couple years, and he urged me to go there to make work, particularly in Rome. “It’s like New York 25 years ago,” he said. “It looks amazing, and no one cares if you take their picture.” But that week, the coronavirus-related travel ban had just been announced, and he was dismayed by the separation this was likely to create between him and his Italian girlfriend and his work there. That night we shared the vain hope that the pandemic would pass more quickly than was feared. Today this all feels like a million years ago, but that night the bars, restaurants, and some galleries were still open, and we stood closer than six feet to each other while he smoked his ever-present hand rolled cigarettes. I wish I had taken a photo of him that night. I didn’t know that conversation would become so important.

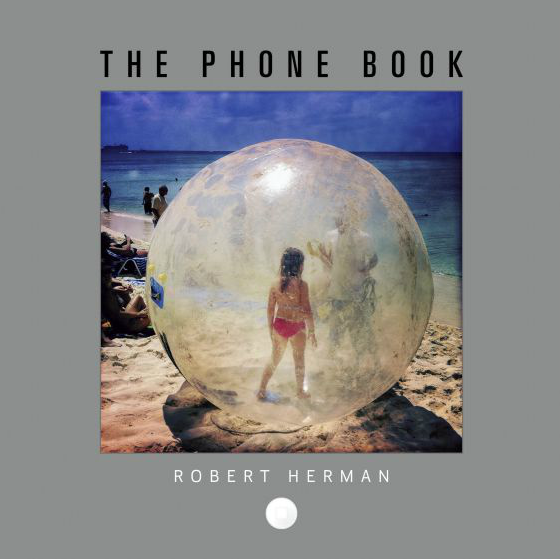

Robert was the author of two monographs: The New Yorkers (Proof Positive Press), a collection of his New York City photographs shot on Kodachrome between 1978-2005, and The Phone Book (Schiffer Books 2015), a collection of iPhone photographs made using the Hipstamatic App’s square format while traveling across the world. The Phone Book was chosen as one of the best photography books of 2015 by Elizabeth Avedon. His photographs are in the permanent collections of The Museum of the City of New York, The George Eastman House, The Telfair Museum in Savannah GA and the Mario Franco Archives/Casa Morra Foundation in Naples, Italy. He had numerous exhibitions. Robert earned a Masters in Digital Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York City, and a BFA in Filmmaking from New York University. He gave workshops and masterclasses in New York, Los Angeles, Texas, Massachusetts, and Italy.

Sean Corcoran, photography curator at the Museum of the City of New York writes, “I met Robert in the mid-2000s when he came in to show me his work that would later be included in his book ‘The New Yorkers.’ At the time I remember being struck at how well the photographs represented not just a time in New York, but the remarkable way that photographs reflected Robert’s experience of the city. We spoke for hours about the work and it was clear that photography was not only a creative outlet but also a way for him to connect with the world around him. In nearly all the photographs in that body of work rarely is there a ‘stolen’ photograph––the subjects of his lens know he is there and there is a connection, some kind of engagement. To me, that was what elevated his pictures.”

Jaime Permuth, Robert’s classmate from the SVA Masters program (where he is now an instructor himself) adds, “Robert Herman was a New Yorker through and through: sophisticated, combative, opinionated, a man of irrepressible wit and the deepest passion for photography. He was unapologetic, eccentric and talented. I loved him for all of those reasons. His remarkable photographic legacy will endure, as will his place in the hearts of those who were fortunate enough to count him a friend.”

A community member (and artist) like Robert will not be easily forgotten. In the world of the arts we tend to see only the remaining relics of a career output as the departed’s legacy, but as his close friend, photographer Mark Brown, reminded me, Robert has left behind a kind of permanent change in others’ seeing and memory: “I will miss my friend Robert Herman. When I once again find myself walking down the same streets that Robert loved, I will think of my friend. I will think of our yelling match on Broadway and 23rd Street. I will smile to myself when I walk down 5th Avenue remembering how he couldn’t walk three steps without bumping into me. When I walk past Gramercy Park, I will remember the time I ran into him, with a friend and he exclaimed, “Oh! I was just talking about you!” The streets will be that much more empty knowing I will never bump into him again.”

Robert Herman received a BFA in film making from the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University and received his Masters in Digital Photography from the School of Visual Arts in NYC. Later as a production still photographer on independent feature films, Herman discovered the life at the periphery of film locations was more compelling than the film sets. His book of his NYC color street photographs, The New Yorkers, was published in the fall of 2013 with help from a successful Kickstarter campaign.

New York City is like a diamond mine. The pressure will turn one into coal dust or a multi-faceted jewel. To survive with some sort of evolving grace, it is absolutely essential to cultivate a Zen-like awareness. Consciously choosing to be in a state of openness is also useful for making photographs. To paraphrase the art critic John Berger: A photograph that surprises the photographer when he makes it, in turn surprises the viewer. No matter how hardened and cynical one becomes, the act of taking a picture, forces one to try to return to an innocent wonder. Every time I go out to make photographs, I ask myself this question: Can I see the world with vulnerability and clarity?

The New Yorkers is a body of work that I began when I was still a student at NYU, when I was learning to be a photographer. I was living in Little Italy at the time and everyone around me seemed to be a subject: the man who changed tires, the superintendent of the building next door. I discovered Harry Callahan’s magnificent book: Color and Robert Frank’s The Americans. These images opened my mind to what a strong photograph could be. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then this was my starting point. Both of these photographers re-made the mundane, the ordinary and the everyday and transformed them into small and transcendent jewels.

Over the years, I lived in several different apartments and I continued making pictures in whatever neighborhood I happened to be living in. Becoming comfortable in my new surroundings would ease the way for me to make the authentic photographs I was seeking. Key to this body of work was letting the subject matter determine the outcome. I would make myself available, allowing my intuition to be my guide and let the content rise to the surface. The true epiphany was not to embellish or to judge: with the removal of the internal impediment strong subject matter would speak for itself. Like a man searching for water in the desert with a dousing rod, I became a vessel and allowed the images to pass through me onto the film.

As an illustration of this, “Eldorado” was made on a day when I was sitting around my loft with my girl friend at the time when suddenly I said, “ I’ll be right back, I have to go out and take some pictures.” Ann nodded her ascent and with my Nikon F in hand, I walked around the corner onto Mulberry Street. In the bright afternoon sun two luxury cars were parked angling in from the street towards a large green garage door. I chose my framing just as two boys walked into the shot and I made my picture. I was back at home five minutes later and knew I had captured something truly special. I was at a loss to explain what had just happened. It was truly a mystery. I realized that if I were wiling to relinquish some control, I would occasionally be rewarded with strong photographs. I went out to search for water in order to survive, and I was led to something shining down from the sky and bubbling up from the ground.

There is synchronicity and coincidence present everywhere. Photographs are a way of revealing hidden relationships that are only present for a moment in space and time, seen from a unique vantage point. The New Yorkers is the record of my self-discovery as a photographer, inside and out, manifested on the streets of New York City. – Robert Herman

The Phone Book

I began making photographs with the iPhone in 2010 and started taking it seriously when I discovered the Hipstamatic App. Surprisingly, it was the limitations of the iPhone/Hipstamatic that made it a compelling choice: the square format, the fixed lens and the slow ISO. Unlike a DSLR that has a five-shot burst, it forced me to slow down. With no zoom and no telephoto at my disposal, I had to move. I felt closer to my previous analogue practice than I had in a long time.

Using the Hipstamatic App gave me a seemingly exponential number of lens/film pairings to choose from. After some experimenting, I found a lens/film combination that pleased me. I wanted to echo my previous street work with Kodachrome and Tri- X. Using a clean “lens” and a “film” combination added warm saturated colors to the image. For black and white, I used the same clean “lens” with a high contrast, grainy “film”. Most of the photographs in this book were made with these same lens/film combinations. Working this way, I hoped to create a consistent body of work.

Although I’ve moved from shooting film to the DSLR and then to the iPhone, my method has remained consistent throughout my thirty-five-year practice of street photography. I am drawn to the spontaneous, unforced event. I see myself as a vessel, witnessing and recording a moment in time and space. I respond to the visual stimuli before me, making decisions based on instinct and experience. In the past, there was always a part of me that found it slightly inauthentic and artificial to go out with a camera and look for pictures. The iPhone allows me to put aside this artificiality and shoot whenever and wherever I am. It is a joy to always have a camera with me when the muse strikes. – Robert Herman

Rest in Peace, Robert. You will be missed.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

2023 in the Rear View MirrorDecember 31st, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Staff Favorite ThingsDecember 30th, 2023

-

Inner Vision: Photography by Blind Artists: The Heart of Photography by Douglas McCullohDecember 17th, 2023

-

Black Women Photographers : Community At The CoreNovember 16th, 2023