Project 2020 at the Los Angeles Center of Photography

In just three weeks, the photography world as we know it has radically changed. A big part of that change is the loss of our access to work on the walls. The Los Angeles Center of Photography has a beautiful exhibition, Project 2020, hanging on it’s walls and unfortunately it can’t be fully appreciated. So, we are sharing it here.

Juror/Curator Douglas Marshall selected twelve projects that represent the range of terrific work being created today. The exhibition includes work by Harvey Castro, Tracy L Chandler, Lisa Cutler, Elisa Ferrari, Matthew Finley, Mimi Fuenzalida, Donna Garcia, Rohina Hoffman, George Katzenberger, Ann Mitchell, Jenna Mulhall-Brereton, and David Wolf

Douglas Marshal shares his Juror’s Statement:

After viewing nearly 200 individual portfolios, I found it incredibly difficult to select a dozen finalists. The projects exhibited, I feel, are those that most successfully accomplished the artist’s stated intent and were confidently edited, while providing a new platform for under-represented stories and innovative approaches to the medium. As in many portfolio reviews in recent years, a clear takeaway of interest and optimism for me was the prevalence of socio-political and data-driven work being made by contemporary photo-artists. Evidence of a universal need to do something and to stimulate dialogue when witnessing injustice or apathy. Many artists sought to address overlooked histories and stigmatized groups through aesthetically engaging and thoroughly researched work, some traveling great lengths on their own accord to complete their project. Others engaged with the chemical and physical aspects of photography, exploring its unique ability to skew time and “truth”, which traditionally it is assumed to faithfully represent with instant accuracy. In the end, each artist’s body of work submitted is worthy of honest critique, and I hope that each applicant continues down their creative path with renewed energy, inspired as I have been by the selected projects.

Douglas Marshall is an LA-based independent curator and consultant at Marshall Contemporary. Marshall was formerly Director at Peter Fetterman Gallery, Santa Monica from 2012-2017, and Galerie XII Los Angeles (2018-2019) producing over 60 exhibitions and art fairs dedicated to leading photographers across the history of the medium with a focus on humanism, landscape, pictorialism, and street genres. Through his current roles in the field, Marshall now works to bring emerging and innovative international voices in contemporary photography to the American market through collaborative projects with artists, galleries, and fairs.

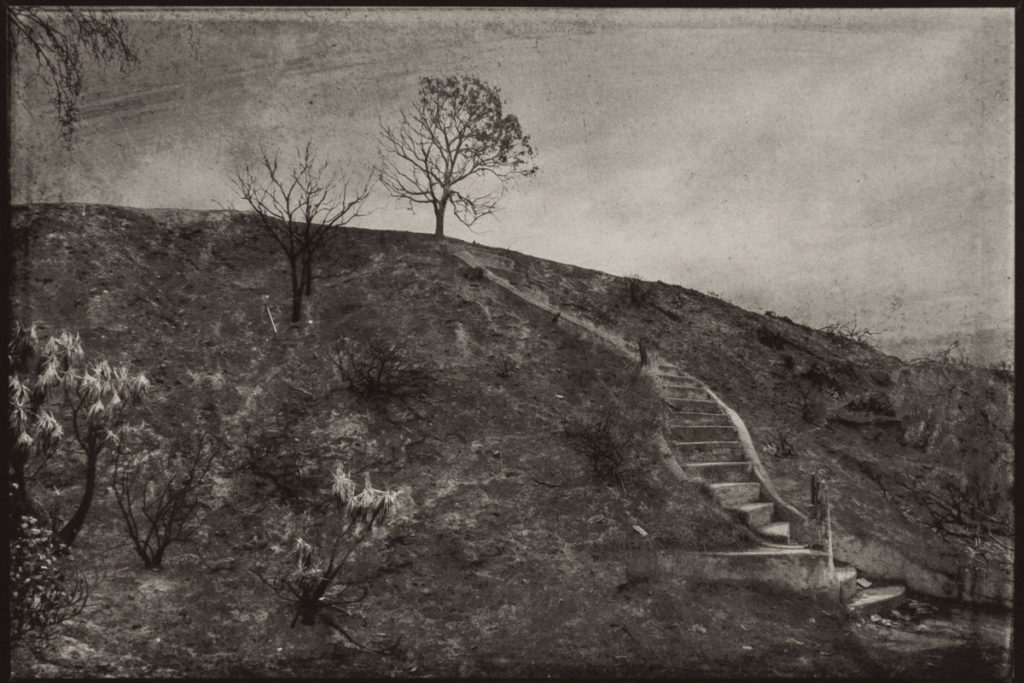

Chance Chronicles

In this series of constructed images, I have created a world that feels somewhere between a dream and a cinematic still. A world where we have a sense that the space and narrative continues beyond the frame, with echos from a past existence. The title, Chance Chronicles, comes from the process I used to create the images, starting with a randomly selected written meditation prompt. I then start writing and the writing process leads to me images…which are the basis for the work you see here.

Beginning with a warm, monochromatic palette to impart a sense of nostalgia, I use a visual language of objects that weave man-made structures into a place where nature is returning. These are spaces of transition and I like the idea that in a balance between man and nature… nature will eventually have its way with us. The objects within the frame are the characters – they embody hope, loss, life, age, strength…that is their role in these landscapes. Visually, I’m fascinated by the narratives/dreams that come to mind when I find abandoned places, and I’m drawn to western landscapes where the sky seems to go on forever, where there’s enough space for waves of those dreams.

In creating these scenes, I work with my own imagery and that has taught me to look for scenes that are both evocative and non-specific to allow the viewer to remain in the “authenticity” of this new world. For this series I created a set of textures taken from a variety of vintage traditional processes: the glass from old proof frames, the edges of wet plates, even aging film by leaving it out in the elements. The images are printed in hand-coated Platinum / Palladium, a 19th Century process known for its beauty and mark of the hand. I have also created a series of short (15-30 secs) animations that bring several of them to life. – Ann Mitchell

Douglas Marshall states:

Ann Mitchell’s series of surrealist platinum landscapes from “Chance Chronicles” represent a uniquely fictional, and intriguing, divergence from a majority documentary-based group of submissions. A sense of other-worldly nostalgia permeates her prints which feel like a postapocalyptic Western viewed through the hazy palette of early pictorialism.

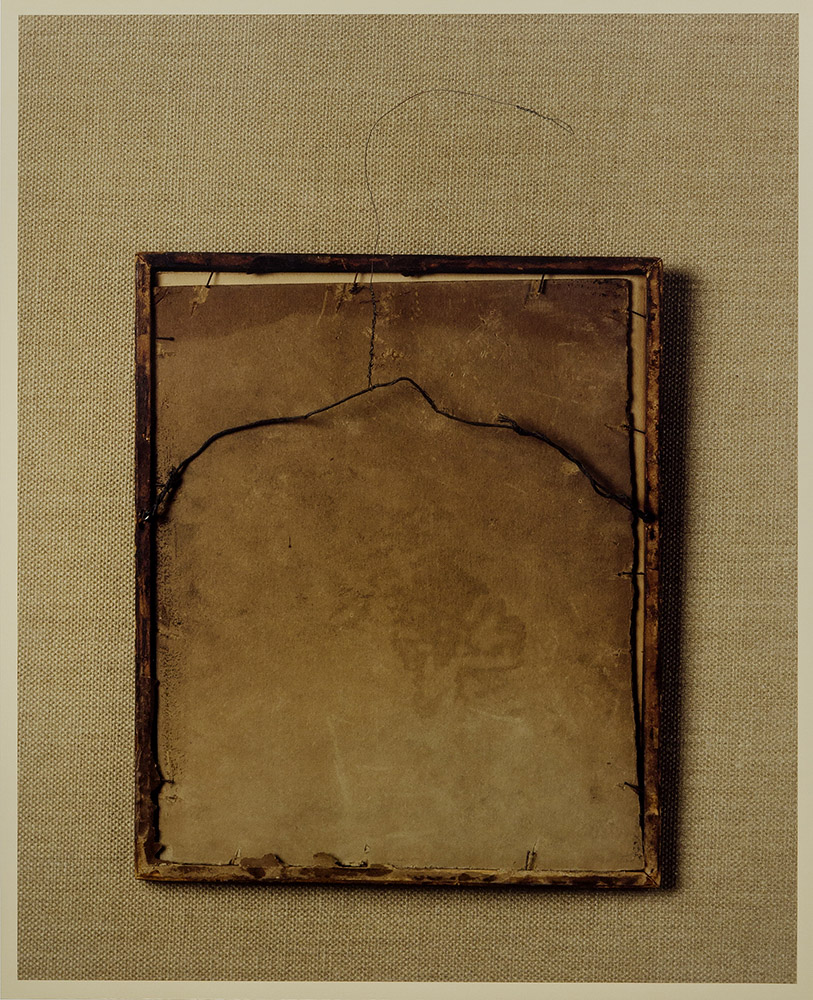

The After Life of Things: Discarded, Collected, Assembled

The After Life of Things: Discarded, Collected, Assembled explores the materiality of things and the nature of photographic materials, while celebrating the wonder of the traditional darkroom in an age of its demise.

The project is about photography itself, both its practice and means of representation, its history and place in contemporary art. With digital media and the virtual world now firmly established in our collective experience, this project celebrates the persistence of the physical object and its life in our imagination.

Objects serve as markers in our lives, connecting us to people and places. Our relationship to things is rooted in the physicality of the object itself, and yet enters the emotional life of our memories, identity, and desires.

I draw a parallel between discarded objects and discontinued photo papers as found objects, utilizing the typically unwanted color shifts and random marks characteristic of expired papers as a metaphor for impermanence and mortality.

The photographs are both images of objects and objects themselves. Many are printed life-size from large-format negatives to emphasize the physical presence of the object. Considerations of image scale, color balance and shape contribute to the creation of works defined by the unique qualities of the selected paper, many of which are one-of-a-kind.

The project’s subject matter has grown organically over the several years I‘ve pursued this work, evolving to include imagery inspired by collected objects as well as cameraless images. A diversity of subjects speak to a range of human experience, including the idea of home, our relationship to nature, and the shifting boundaries of the sacred and profane.

Most surprising has been the cameraless imagery, whose process uniquely isolates the effects of time on aging photographic paper. What results is the raw material for abstraction, often showing a striking parallel to Modernist painting. – David Wolf

Douglas Marshall states:

As a curator intrigued by photography’s renewed exploration in physicality, I believe David Wolf’s project “The After Life of Things” strikes a contemporary chord by translating weathered objects through an equally fragile medium prone to chemical degradation. Each work in Wolf’s unique presentation explores a new method of visually alluring construction, showing that his interest in process is paramount.

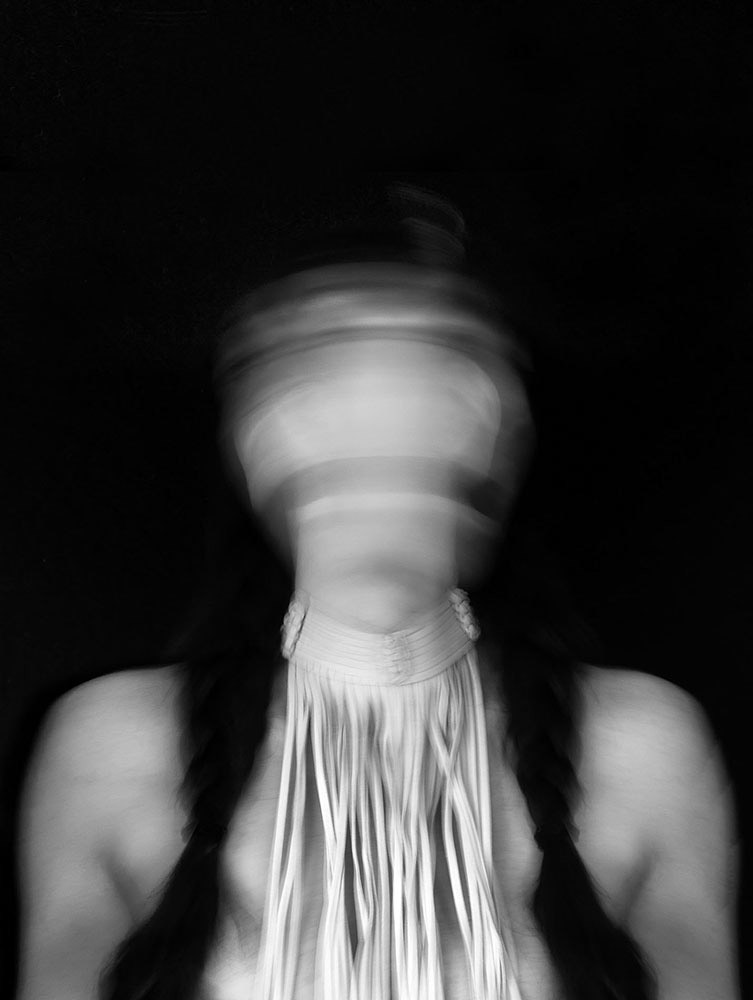

Indian Land For Sale

In 1830 the Indian Removal Act was enacted.

President Jackson declared that Indian removal would “…Incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier. Clearing Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi of their Indian populations would enable those states to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power.”

Systematic hunts were made to force indigenous people from their ancestral land.

A Georgia volunteer, later a Colonel in the Confederate service, said, “‘I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Indian removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”

Following the signing of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 the American government began forcibly relocating East Coast tribes across the Mississippi. The removal included many members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations from their homelands to “Indian Territory” in eastern sections of the present-day Oklahoma. It was a 1,000-mile walk and took 116 days from Georgia, walking all day and only being allowed to stop at night to bury their dead.

Between the years of 1830-1838, 100,00 indigenous people were “removed” from their ancestral lands. Although, no one is sure the exact number, approximately 21,700 Muscogee and approximately 16,500 Cherokee were removed by 1831.

Not all indigenous people left in 1830, specifically the Cherokee. Many stayed, thinking that they would be allowed to live peacefully or have the ability to fight back (actually winning several legal battles against the removal order). However, the Georgia State government and Andrew Jackson, had plans for their land. Flyers began to circulate hailing “Indian Land For Sale”. White farmers flocked in droves to auctions of indigenous, ancestral land that was still, up to 1838, being occupied by its native people.

It was in 1838 that 7,000 US soldiers in Georgia enforced a final evacuation. The Cherokee, Creek, Shawnee and Choctaw villages were invaded and the people were forced to leave, at gunpoint, with only the clothing on their backs.

For the few who resisted, approximately 1,800, died while imprisoned for refusing to leave.

Historians such as David Stannard and Barbara Mann have noted that the army deliberately routed the march of the Cherokee to pass through areas of known cholera epidemics, such as Vicksburg. Stannard estimates that during the forced removal from their homelands, 8000 Cherokee died, about half the total population. Half of the Choctaw nation was wiped out and 1 in 4 Creek.

A Cherokee survivor of the trail told her granddaughter, “The winter was very harsh and many of us no longer had shoes. Our feet froze and burst, as we left bloody footprints in the snow. We were not allowed to stop to bury our dead. Many mothers carried their dead children, miles, until we stopped at nightfall. All night you could only hear digging.”

The deportation of indigenous tribes along the Trail of Tears was an act of genocide that has been conveniently forgotten today. On March 30, 2020, the federal government revoked reservation designation for the Mashpee Wompanoag tribe and has removed their 300 acres of ancestral land on Cape Cod from federal trust. This recent government land grab is raising grave concerns among indigenous advocacy groups across the country that all tribes could now be at risk – again. – Donna Garcia

Douglas Marshall states:

“Indian Land For Sale” by Donna Garcia sheds an artistic, albeit subdued and haunting, light over one of America’s darkest historical infringements on humanity. The images she has created to interpret stories from the Trail of Tears don’t feel overly dramatized, despite their unsettling nature. On an aesthetic level, her photographs are texturally and tonally vivid, symbolic of the undoubtedly strong imprint left on the memories of survivors.

Can you hear the sounds of life

In the roaring of the creek

In the blowing of the wind

That is all I want to say

That is all

-Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (Sami poet, 1943-2001)

In the bone chilling European Arctic, reindeer migrate across borders picking up the scent of food with their noses against the wind. Their grazing and calving patterns are closely monitored by Sami reindeer herders who have followed the reindeer since the last ice age. The Sami are Europe’s only recognized indigenous population and live in a region, known as Sápmi, which covers the Arctic area of Sweden, Norway, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. Their ancestral lifestyle related to the seasonal migration and herding of reindeer, is still practiced today by a small percentage of Sami reindeer herders and is at the heart of Sami culture and identity. This unique cultural experience as pastoralists has yielded a profound connection and understanding of nature that traditionally has been passed down from generation to generation, but is now facing great challenges due to climate change and development in the Arctic.

Today, the Arctic is experiencing the most extreme temperature increases on the planet. As a result, the region is suffering from coastal erosion, rising sea levels and tree lines, loss of biodiversity, shrub invasion in the mountains, reduced sea ice, and loss of animal habitats. This situation is especially volatile in Northern Sweden, where unstable weather is leading to seasonal shifts that alter the freeze-thaw cycle and affect vegetation and animal life, making the herding of reindeer more dangerous, expensive, and unpredictable.

In response, many Sami have become activists, using art, politics, and science to implore the land be protected for their culture, livelihoods and most importantly, for future generations.

These images are part of a larger body of work supported by a 2019 National Geographic Explorer grant from the National Geographic Society that explores stories of Sami acts of stewardship. – Elisa Ferrari

Douglas Marshall states:

Photographic calls for climate change awareness often seek a balance between documentary and fine art, perhaps in an attempt to lend one’s unique voice to the fight. Elisa Ferrari’s portfolio from “The Sami Way” thankfully continues this trend with a humanist, yet graphically powerful, photo documentary studying the effects of a warming and over-extracted planet on Arctic reindeer herders. Ferrari’s in-depth focus on one remote community is strongly edited to strike an important and effective balance between alluring and informative.

Imposters

This photographic documentary is comprised of photographs revealing the strange existence of intentionally hidden, full size, artificial “trees” scattered throughout our environment.

These impostors are seen in our school playgrounds, our parks, in church parking lots and even in pristine natural settings. In what is known as “stealth” by the industry that hides these “trees”, they can often be virtually undetectable.

By using infrared photography, I betray these dark pretenders beside spectral white, but genuine, trees and humorously, yet eerily, reveals the blurring boundaries between the real and the surreal. – George Katzenberger

Douglas Marshall states:

George Katzenberger’s series of “Imposters” shows a creative and intelligently humorous technical use of the medium through his infrared docu-landscapes. The presence of these cell-phone tower trees have always amused me, but Kaztenberger has really exposed them in an informative way that leaves the viewer to reconsider taking our urban landscapes at face value. It is not only a unique idea but well executed with strong compositions that would hold their own even without the magical revelation of “dark pretenders”.

Los Olvidados

In February of 2006, I was driving cross-country, moving back to California from New Hampshire. I arrived in New Orleans in the middle of the night. The following morning I programmed my GPS to take me to a gas station on the way to the airport. It had been five months since Hurrican Catrina hit New Orleans and my first time witnessing what was left behind.

Ten months had passed since Hurricane Maria made landfall on the shores of Yabucoa, Puerto Rico. So in June 2018, photographer and friend Dan Fenstermacher and I traveled to Puerto Rico, to confirm the stories of Perto Rico being back to normal. When I was in New Orleans in 2006, the only people you saw on the streets of the most affected areas were workers in hazmat suits. This time around, I traveled with the express intent of giving voice to those still affected. Among them, Angel “Don Angel” Gonzalez of Salientito, Jayuya. An 84-year-old man that was legally blind living alone with his dog, Paloma. Angel had been living without running water or electricity since the hurricane. After we left the town of Jayuya, it became clear to us that we had to start sharing these stories and find a way to help. We did, and Don Angel’s story ignited a grassroots campaign to get him the help he needed.

For me, this work is a reminder of the power of an image to evoke action and the importance of listening and providing space to grieve. Don Angel is no longer with us, but his message of love and selflessness is one I carry with me. – Harvey Castro

Douglas Marshall states:

We rely on social-documentarians to personify the 24/7 news-cycle but some, such as Harvey

Castro, are able to inspire concrete, positive action through their enlightening efforts. His project investigating post-Maria Puerto Rico, “Los Olvidados”, includes a number of portraits akin to Gordon Parks’ impactful story of Flávio, accomplishing similar concern and welfare efforts for a member of the opposite generation. The island’s reputation for familial closeness and natural beauty now competes with blue tarps as a symbol of cultural identity, an unfortunate situation expertly illuminated by Castro.

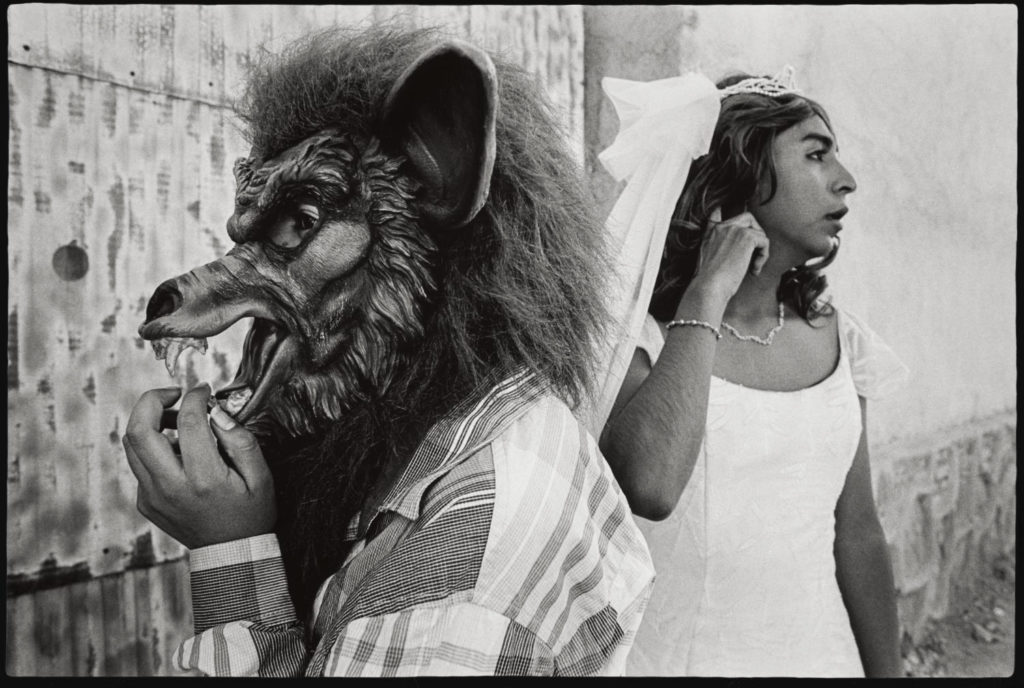

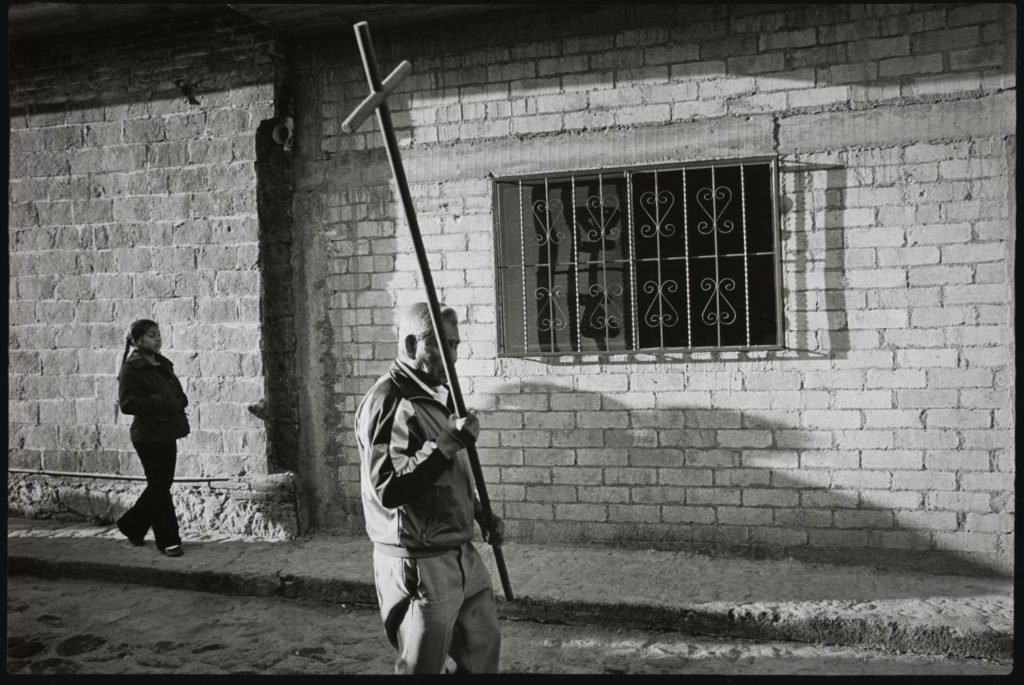

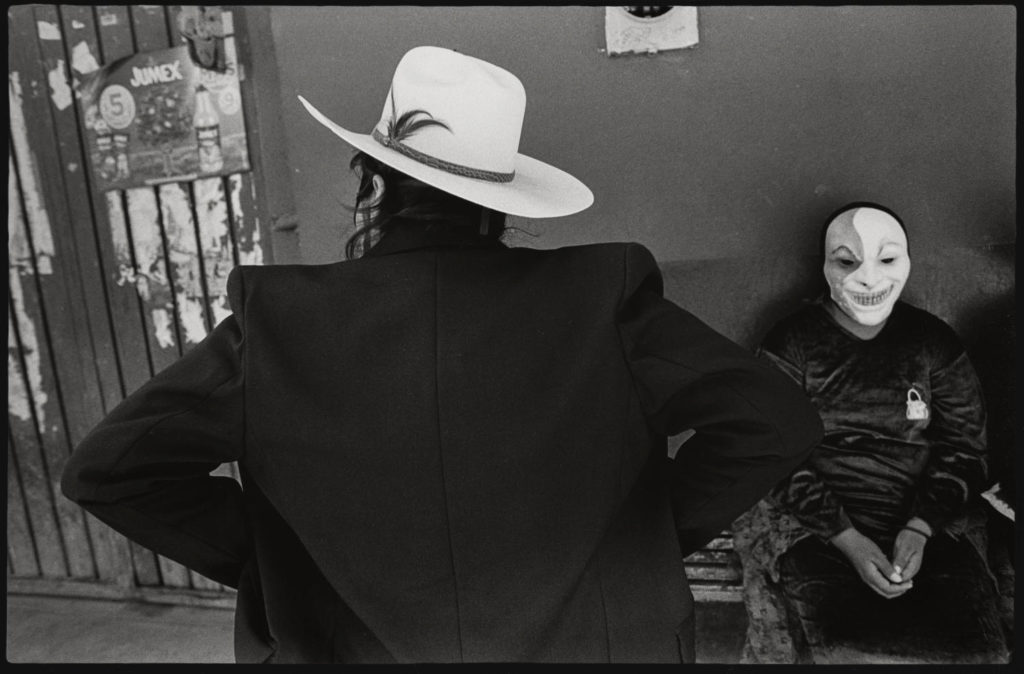

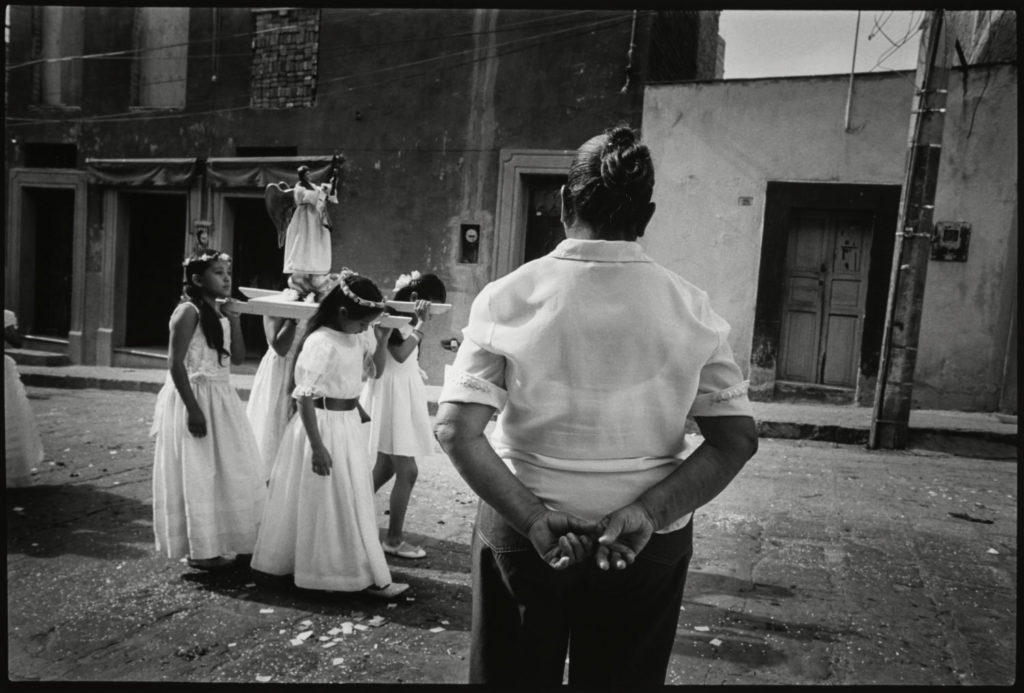

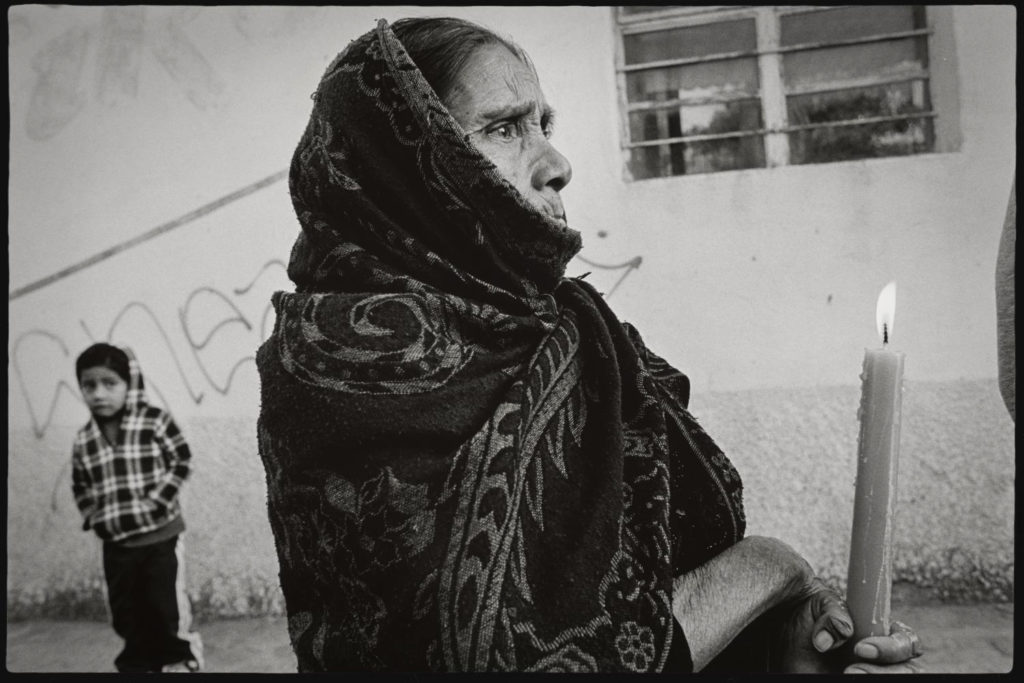

Sacred/Sagrado: Festivals of Mexico

These photographs are from the series Sacred/Sagrado: Festivals of Mexico. I began the project in 2011, and since then, I have been traveling to various communities in the country to witness and document traditions that are part of the fabric of Mexican culture.

The term “sacred” invokes two distinct definitions of the word: that which is holy, and that which is a cherished part of the life of a community. Though all the festivals I have photographed tie back in some way to the religious calendar (Mardi Gras, after all, is the day before Lent), only about half of them celebrate the deeply held beliefs of the Catholic faith. Other images portray a profound sense of tradition, identity, and community that is every bit as intensely felt.

I have a strong interest in what is meaningful to communities and cultures and how those values are expressed. I am intrigued equally by that which is universal—the powerful beauty of everyday moments of human connection—and by the unique expressions of a particular culture. In that sense, I hope that viewers encounter—and bring curiosity to—both the familiar and the unfamiliar in this series.

Individual images from Sacred/Sagrado: Festivals of Mexico have appeared in a number of exhibitions across the US, and the Pearl S. Buck Museum in Perkasie, Pennsylvania, held a solo exhibition of the complete series. The project is available to travel. – Jenna Mulhall-Brereton

Douglas Marshall states:

In “Sacred/Sagrado”, photographer Jenna Mulhall-Brereton takes us through a dual-exploration of sacred festivals in Mexico, highlighting their religious traditions and communal influence. Using a monochromatic silver palette, Mulhall-Bereton’s intimate, sometimes askew, compositions showcase an honest humanity, mixed with a dash of mystical surrealism, reminiscent of the earlywork of Sebastião Salgado and Flor Garduño. Her ability to move seemingly undetected throughcrowds, never drawing the eyes of her subject, allows the viewer a nearly firsthand experience.

Red Hook

I discovered Red Hook by chance, making a wrong turn getting off the Smith Street Train Station in Brooklyn. Over the course of the next two years, I returned to photograph this urban, gritty wonderland. I find a post industrial part of the city where the story is in the quiet details.

Roode Hoek, as named by the Dutch colonists who settled there in the 1600s, was named after the point of land that stuck out into the New York Bay, and the red clay soil upon which everything is built. On the surface it seems somewhat desolate, but is in fact in a constant state of flux and activity. It’s an especially disorientating space; constant change makes physical markers for navigating the streets unreliable. What was there one week, would be gone the next. However, there is the looming Gowanus Expressway. If you look, you can find it almost everywhere.

It reminded me of the disorientation I experienced when the Trade Towers disappeared—the physical anchor of the Trade Center that defined the downtown skyline, and imprinted on one’s psyche, was now absent. Within this impression of disorder, my photographs bring about a certain level of re-stabilizing, through a formal use of the photographic frame, use of vertical and horizontal lines, juxtaposed and layered upon the physical and visual chaos that I see before me. The vertical line replaces what is missing in this neighborhood. The tall buildings and the trees have all been stripped from the environment. We see strength and dignity in the in gates and lamp posts and the fences.

Dilapidated, abandoned buildings sit beside renovated architecture. Alongside the Victorian warehouses, are newly-built apartments. What comes to mind are cubist structures, particularly their foundations—the blocks and the cubes left from the industrial revolution. Building and destruction—we are left with the cube.

In my photographs, I do not embellish or glorify what I see. I am interested in discovering beauty away from traditional aesthetics. There is no artifice, with each scene photographed as I have found it, trash and all.

I have found my journey through Red Hook, fascinating. Empty lots make me wonder what was there before, overgrown playing fields conjure the cheers of playing children. At once enthralled, but also somewhat saddened by the change. It makes me think about what Fritz Leiber—a writer of American Horror and Science Fiction in the early 1900s—wrote to a student; “Your picture looks like the breaking apart of the modern world. Families, nations, classes and loyalty are all falling apart. Things changing before you know them”. – Lisa Cutler

Douglas Marshall states:

In Lisa A. Cutler’s project “Red Hook, Brooklyn” we see the prevalent scars and layered textures of America’s post-industrial landscape. Her photographs thankfully avoid the trope of “decay-porn” and instead lock the viewer with a straight-forward, objective exploration of urban neglect, conjuring honest concern for the citizens who are nowhere to be seen.

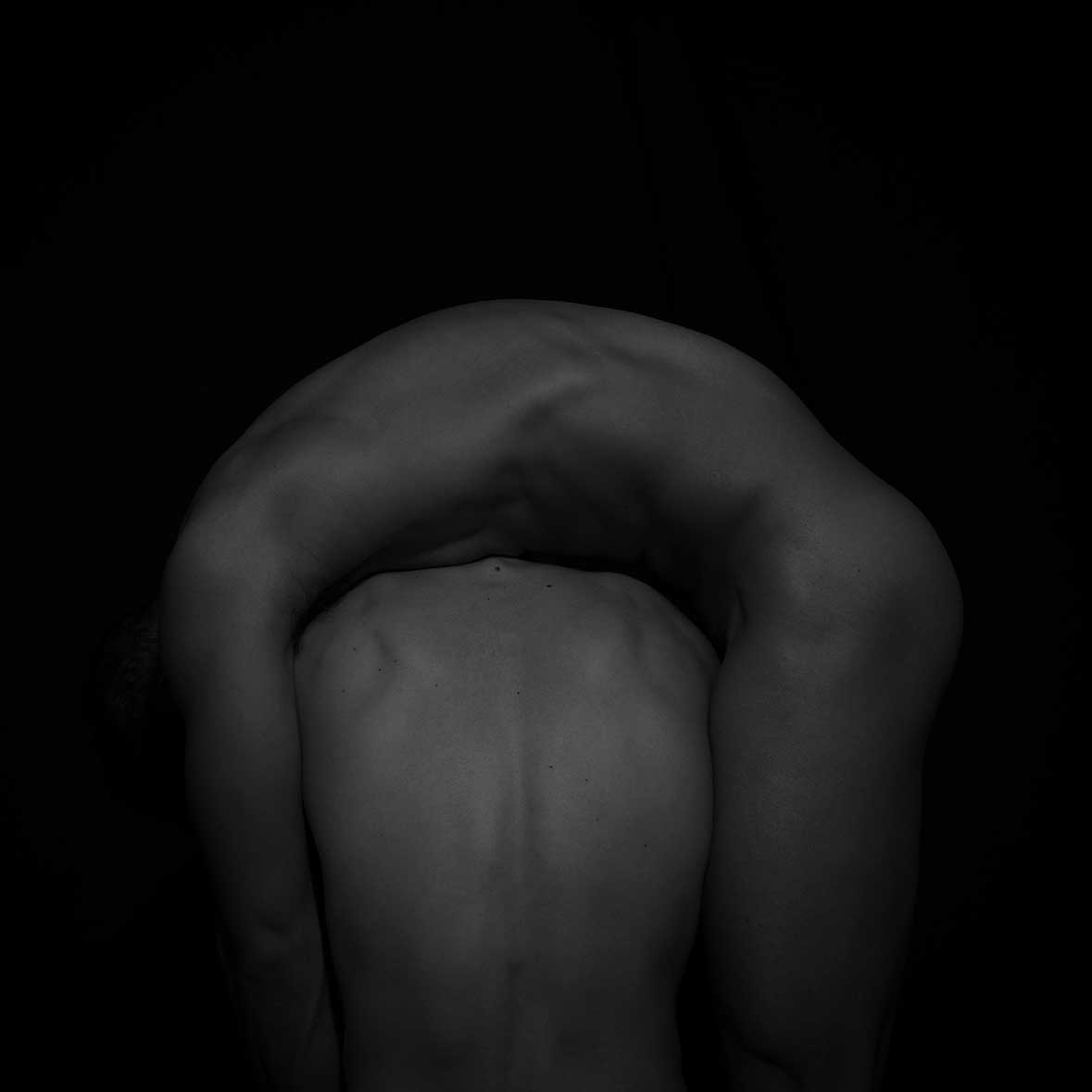

The Shape of Us

This series is a testament to the beauty that can be created between two men. Inspired by my own long-term relationship, I sought to construct and celebrate the strength, complexity and intimacy possible, while purposefully adding positive gay representations that were practically nonexistent while I was coming out as a young gay man. Lacking in same-sex relationship examples, I was unsure I would ever experience this type of closeness.

While our society has grown and changed a great deal since I came out over twenty years ago, there are still many people today that believe images like the ones I am creating are wrong or perverse. Reflecting emotions that we all experience—intimacy, connection, and acceptance—I aim to forge a moment of recognition and understanding.

Using bodies in both emotional and abstract relationship, I explore the push and pull that can happen over time as two lives come together to create a unique, new shape that hadn’t previously existed. It is in this spirit of creative effort that I carve out this place for a tribute to the beauty of connectedness. – Matthew Finley

Douglas Marshall states:

Matthew Finley’s monochromatic masculine forms from his series “The Shape of Us” are visually seductive while still successfully translating his emotional intentions. While they have an aura of homoeroticism, they are not overtly sexual, and the figures remain anonymous allowing the viewer’s imagination freedom. The photographs investigate muscular topography as much as complex relationships through deeply symbolic shadows and physical connection.

I Do, Still

Marcy and Scottie Jeanette are a middle aged married couple living in a beautiful craftsman house in Los Angeles. They describe their relationship as full of laughter and love.

Despite a fourteen year age difference, Marcy married Scott in April, 1989. Having experienced two failed marriages, Marcy felt she had finally found her soulmate in Scott; someone romantic and attentive to her needs, someone with whom she laughed a lot and who made her feel safe.

One morning twenty years into the marriage, Scott burst into tears. He confessed to Marcy that he thought he was a woman. At first, Marcy thought Scott was going through a midlife crisis, but she soon realized her husband had been suffering all his life with gender dysphoria — he wasn’t able to maintain the façade any longer.

According to a 2016 report <https://www.gminsights.com/request-sample/detail/2926> , it is estimated that nearly 1.4 million adults in the U.S. are reported to be transgender. As the idea of transexuality finds social acceptance, more transgender people are opting for gender affirmation surgery. Of the 3,256 surgeries that have been reported in the United States, 54% were male-to-female. Of those numbers only a small percentage had a spouse by their side during the process.

Marcy began to educate herself in an effort to understand what her husband was experiencing. Scott — who now wanted to be called “Scottie Jeanette” — began seeing a therapist. Together they spent five years grappling with their secret in silence, telling no one what they were going through. As they embarked on a deep journey of discovery as a couple, life threw many more challenges their way — including a devastating turn of events they never saw coming .

This story deals with the complex array of emotions, values and cultural imprints Marcy and Scottie Jeanette were forced to confront as their marriage was put to the test.

Are you going to renew your vows?, their friends asked . Our vows are doing pretty well -Marcy replied – but I wouldn’t mind doing an -I Do, Still – celebration, she added. And so they did.

Through a series of 14 portraits (8 shown here) paired with honest quotes from Marcy and Scottie Jeanette, we follow the two as they open up about the most intimate aspects of their relationship in transition. – Mimi Fuenzalida

Douglas Marshall states:

“I Do, Still”, a deeply personal, beautiful and ultimately traumatic story of images by Mimi Fuenzalida inspires a level of universal human empathy few can. Perhaps it’s their seemingly domestic neutrality on the visual surface that allows for such emotional impact as a whole. The artist’s use of quotes on each image, brief insights of context, is a welcome addition to the stills. The series left me stunned and poignantly humanizes an important point of socio-cultural consideration.

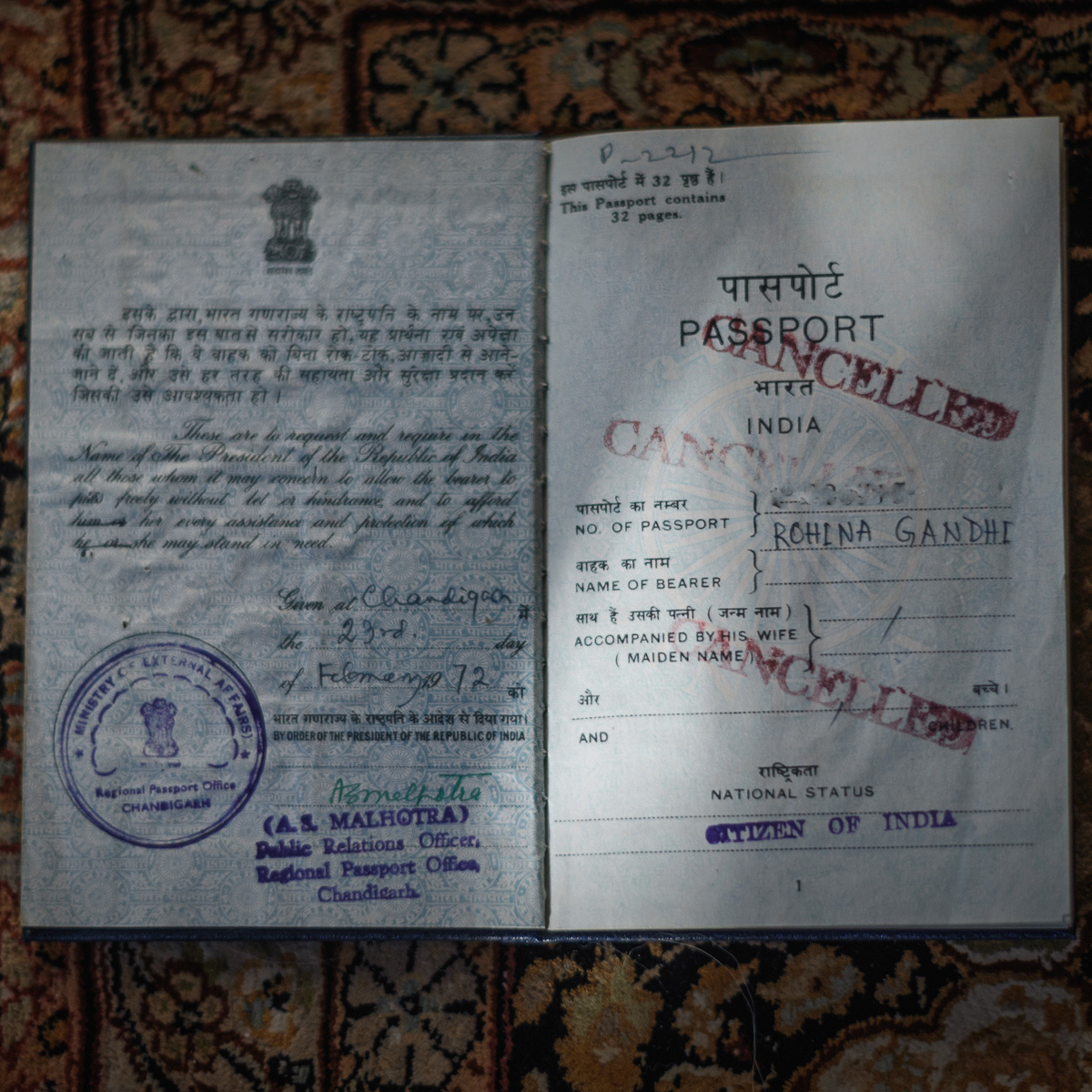

Generation 1.75

On the day I was born in India, my father flew to Queens, NY to finish his medical education. My mother followed three months later and I was left to be raised by my grandparents. As a young child I knew that my parents lived elsewhere, and that I was in a temporary habitat. I felt special but also felt like an outsider in my own homeland. I would often stand on the roof of the house I grew up in and look at the moon and see if I could find my parents.

I came to the United States at the age of 5, reunited with my parents and began a new life in suburban New Jersey. I lived a life filled with expectations: my parents, society’s, my own and what it means to be Indian American growing up in NJ. My project, Generation 1.75 is a metaphorical and lyrical look at themes of loss, unrootedness, and gained perspective in my personal journey of migration, identity, and the emotions that accompany the lifelong exploration of where I belong and who I am.

I often feel of two worlds, sometimes not quite settled, not fully rooted. I am part of Generation 1.5/1.75, a termed coined by Professor Ruben Rumbaut in 1969 to distinguish those who immigrate as children from their parents who immigrate as adults. As immigrant children, there is a discontinuity with our origins due to inherited circumstance beyond our control. This exploration of self, often using the narrative of the natural world, helps me understand the precarious balance of integration and alienation, neither here nor there and then sometimes also both here and there. I am sometimes the alienated insider, sometimes the Other, and at times, fully and easily assimilated. Growing up multicultural can be conflicting and is a constant balancing act, a gift and a burden all at the same time. – Rohina Hoffman

Douglas Marshall states:

Rohina Hoffman’s self-investigative series “Generation 1.75” is rich in deep hues, a reflection of the cultural passion and the story’s emotional weight. While it contains a specific personal interpretation of the social philosophy in its title, her series is inherently universal to the dual identities which child immigrants around the world must balance. The photographs are meditative, mysterious and, most of all, timely to a rapidly globalizing world.

Edge Dwellers

A man stands before us, his black-and-white beard blending seamlessly into the thick tail fur of the wolf skin that rests upon his head. The animal eyes of the headdress are closed in contrast to his intense stare back at us. Both of his hands are ringed with silver jewelry and resting upon his cane as he stands outdoors in what vaguely looks like the beach behind him. The light is soft and natural, the tail-end of the day.

This photograph is one of many portraits in the series titled, Edge Dwellers. The name is derived from many different “edges”. There is the literal edge of the location: the Southern California coast is the edge of the country, the edge of the state, the edge of the city, the edge of land where the vastness of the sea takes over. There is also the figurative edge of the subjects: whether by choice or circumstance the community portrayed here lives outside of the norms of our society. A band of travelers and squatters, some are more transient while others are decades-long fixtures in their community. They have their own rules and routines, sources of comfort and pain. Most of them may be “houseless” but in many instances they have found some sense of home here.

I live in Los Angeles and walk along the beaches and bluffs almost daily. These individuals and their extraordinary habitats are engrained in my regular routine. As I walk and visit, we discuss everything from the petty dramas of everyday existence to the profound mysteries of the cosmos. In some cases, these interactions have turned into artistic collaboration. I have chosen to make work within this community as a way to bear witness, not just to them but to myself as well. As I choose to slow down and see the other as they are, I too feel seen. We together are in every photograph.

Using a large format view camera, I not only need permission but engagement. The process is greatly slowed down, giving the subject and I time to play and to consider our intent. The resolution of the film allows for great detail and large print size, a way to bring the viewer into our shared experience. The consistent but vague background hints at this coastal location but does not distract from the focus on the individual. As you view the series as a whole, you get a sense of the larger community.

In the photographs of the dwellings, the subject and I work together on the same side of the camera to craft their living space as a sculpture, their belongings are arranged just as they like to present them. I kept the frame in portrait orientation as way to communicate that these are not landscapes or still lifes but indeed a continuation of the portrait series, an extension of their personhood.

My intent with this work is not to objectively portray any one group of people but to share my own personal experience of artistic play and to ask the question “What happens when we slow down and just be with the other?” In the past I have used photography as preservation of memory, but in this case there seems to be an evolution of that impulse to freeze a moment in time. By being fully with another, the experience itself becomes the reward. And the resulting photograph is just my souvenir. – Tracy L. Chandler

Douglas Marshall shares:

At the edge of Manifest destiny is an unlikely community of unmatched eclecticism, powerfully humanized in a series of portraits, “Edge Dwellers”, by photographer Tracy L. Chandler. Like many, I’ve often seen many of these characters as just that; Venice Beach attractions more than living, breathing individuals. Thankfully, Chandler, using the patience and collaboration required in largeformat photography has given each subject a profound level of dignity and detail.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and Photography, Part 2January 22nd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and PhotographyJanuary 21st, 2026

-

Dawn Roe: Super|NaturalJanuary 4th, 2026