Alex Turner: Blind River

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Blind River by Alex Turner.

Alex Turner (b. Chicago, Illinois) combines imaging technologies to highlight the profusion of sociopolitical and environmental concerns taking place in the borderlands of the American Southwest. In 2018, he was awarded the University of Arizona Carson Scholarship and N-Gen Sonoran Desert Researchers Grant for his interdisciplinary research and artwork. His work has been exhibited nationally. He was the recipient of an Innovation in Imagemaking Award and was selected to present his work Blind River at the Society of Photographic Education National Conference in March of 2020. A Chicago native, Turner received his BA in Studio Art from DePaul University in 2008 and is currently completing an MFA at the University of Arizona. He splits his time between Tucson, Arizona and Los Angeles, California.

Blind River

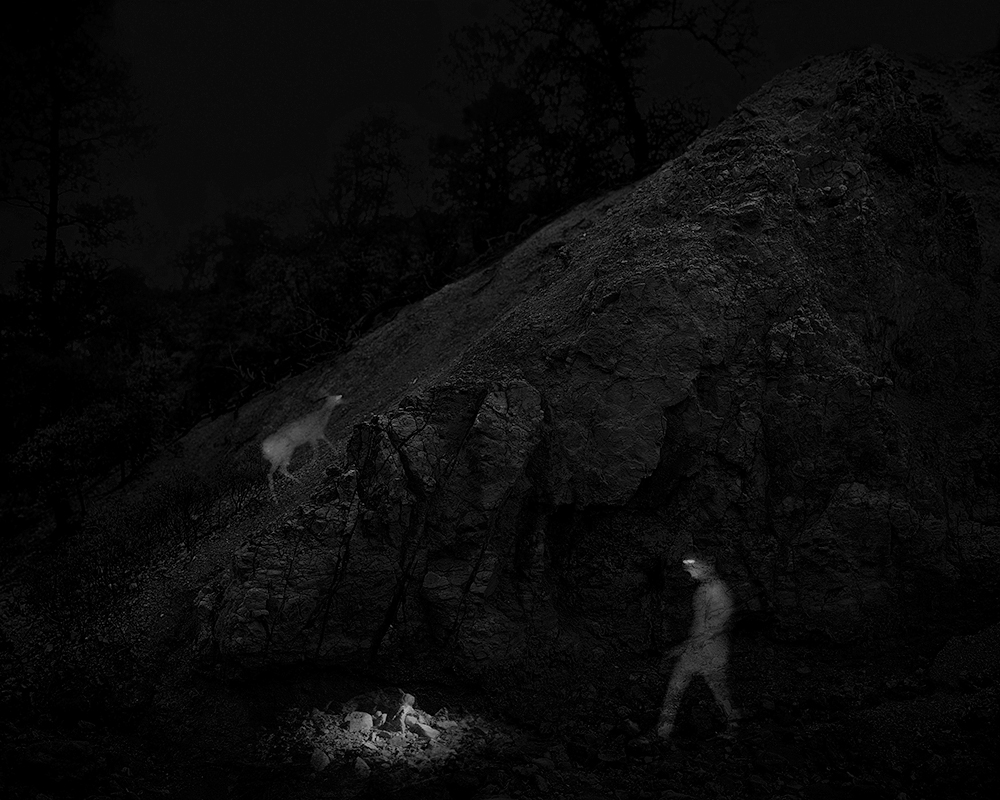

Seasonal rainfall carves washes through the borderlands of the Sonoran Desert. Rains end and water evaporates, yet these channels occupy strata both visible and invisible. Currents often rearrange themselves and flow below ground, less susceptible to the seasonal changes above. Humans and wildlife move through this region in much the same way, forming a complex network of fluctuating corridors across two countries. Political, economic, and environmental forces require them to adapt; their movements are fleeting, varied, and mostly hidden. These systems of transit are subject to constant observation and analysis. Individuals and groups, including scientists and government agencies, study them remotely. Their intentions vary greatly, yet their tactics and data sets often overlap and mirror each other. Merging imagery from their technologies with highly resolved landscape photographs, I collapse intimate and distanced depictions of the border landscape. A new, more comprehensive framework for understanding concealed movement emerges, suggesting a continuous circulation just beyond our unaided vision.

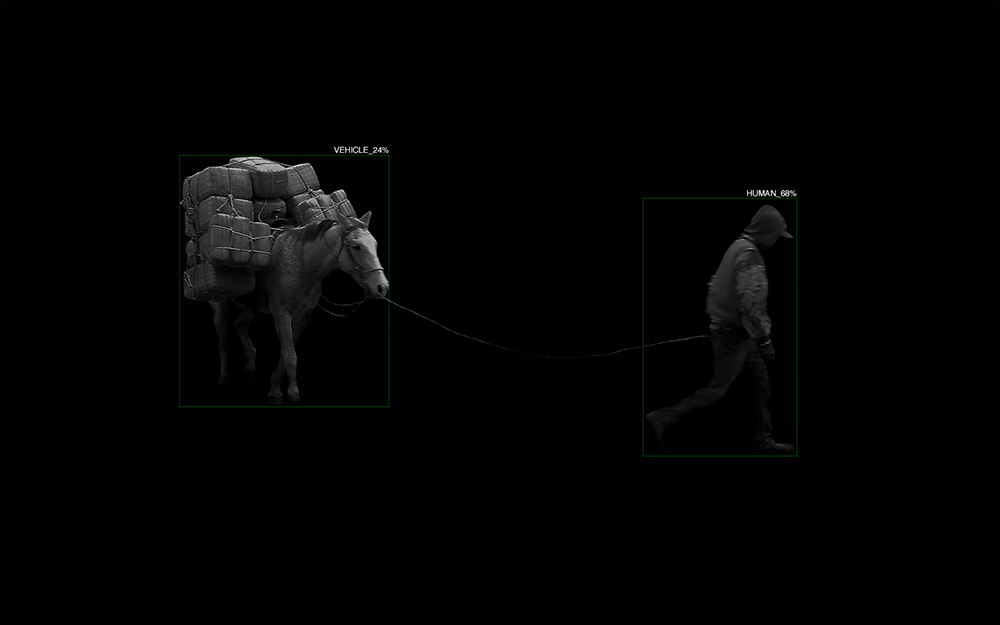

Remote-sensing and recognition applications, whether deployed for research or surveillance purposes, monitor similar spaces, capture similar footage, and analyze data using similar algorithmic tools. Their deployers observe and compile narrow information sets consistent with their motives. In many cases, human vision and recognition becomes secondary: the watcher (camera system) informs the identifier (software) autonomously. Despite these tools of enhanced vision, our capacity to see and understand is clouded by layers of detachment. Does de-humanized observation generate an impassive and simplified lens through which to view this complex and contested space? Is there room for empathy in a system that promotes objectivity? I examine these concerns and encourage viewers to consider subjects and scenes beyond their assigned taxonomies and flattened narratives.

Still, the machine eye watches and collects. In the endless accumulation of footage, patterns emerge and individual moments dissolve. The current reveals our presence and our marks, either ephemeral or enduring.

Daniel George: Besides having moved to Arizona for your education, what drew you to the borderlands for this project? And at what point did you become aware of the monitoring systems in place throughout the region?

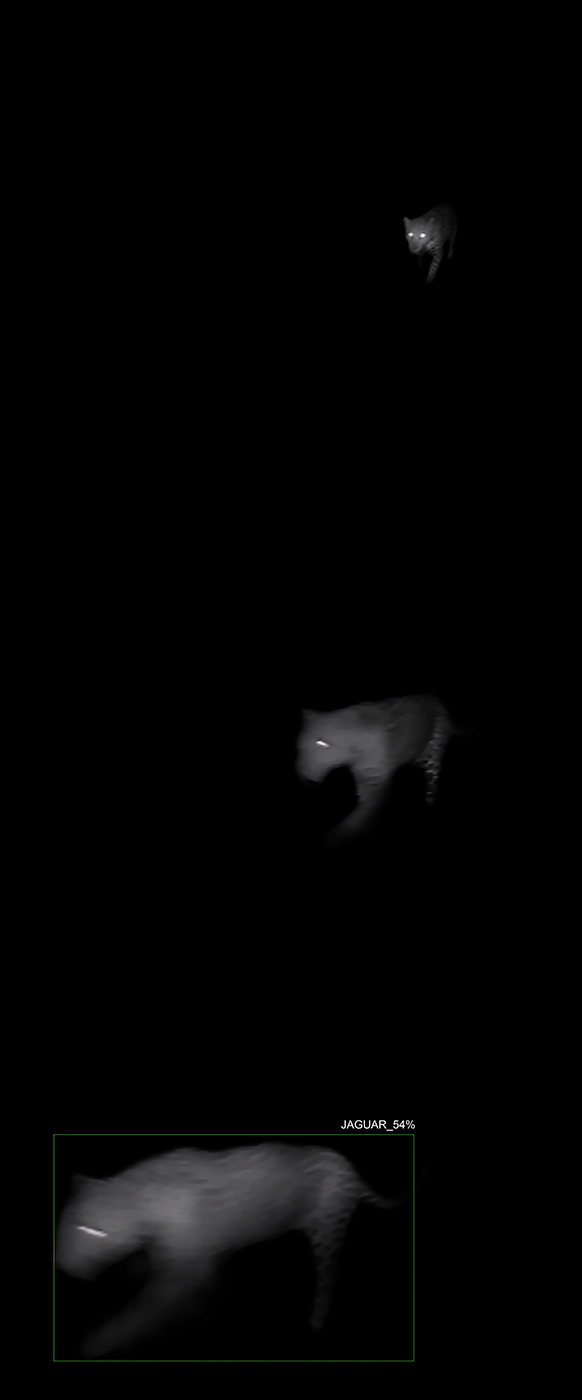

Alex Turner: I had no idea when I first moved to Arizona that I would end up making a project about border surveillance and artificial intelligence. My interest had always been in land utilization and preservation. I had started researching mining claims on federal and private lands near the border and kept coming across news articles and reports detailing their impact on jaguar habitat. Firstly, I was shocked to learn that there were jaguars in Southern Arizona. Secondly, I found it fascinating that this solitary and enigmatic animal few had ever seen was generating such a passionate response from the public.

I decided to reach out to the researchers who, with a large team of citizen scientists, had installed hundreds of remote sensing cameras in a half-dozen mountain ranges along the border to track wildlife migration patterns. The similarities between their research program and the U.S. Border Patrol’s surveillance program in the region are striking. I realized that I was more interested in making work about how we see a landscape than now we utilize it. I wanted to explore both the possibilities and limitations of these monitoring systems, which are nearly ubiquitous now and surveil much more than just remote desert landscapes.

DG: What spurred your interest in utilizing various imaging technologies for this and other projects you have completed?

AT: I’ve always been drawn to art that utilizes technologies not intended for artistic purposes. I think there is something simultaneously attractive and disquieting in the resulting aesthetics of it. I am not the first artist to use infrared technology or artificial intelligence in their artwork, and I won’t be the last. Most often artists repurpose those technologies, but my project incorporates their intended applications. What you see is real data studied by wildlife researchers.

I have the luxury of wearing two hats with this project: I’m an artist but also a citizen scientist. I installed and maintain the cameras, and I am free to use the footage however I’d like. But most of the cameras are owned by the research group, and that footage is logged in their database. It is a unique space to occupy: I am beholden to their research project, but I also have the freedom to operate outside of their methodologies and parameters.

Part of my interest in utilizing these imaging technologies is that I get to explore the gray area between visual art and science. I’ve always struggled with terms like ‘collaboration’ because many have viewed my work as a vehicle for promoting scientific results. I consider this work, and the work of other similar artists, as an opportunity to ask questions and generate new conversations in ways scientists bound by the rules of their field cannot.

DG: I am fascinated by the merged imagery and how it illustrates a blended viewing experience—of both intimacy and distance. Why did you feel it important to collapse these seemingly opposed depictions of landscape?

AT: I remember looking through the footage from the first remote-sensing camera I installed and being shocked at how different the landscape looked compared to how I experienced it in person. Much of this terrain is very rugged and challenging to navigate; it can take several hours of bushwhacking to access some of these cameras. I started thinking about all of the figures that move through here, both human and wildlife, and how infrared imagery on its own does not relay the challenge of traversing this landscape. I wanted to give the viewer a glimpse into that environment, albeit briefly, so that they could begin to understand that challenge. I’m also drawn to the disparity between the two technologies; how the ambiguous infrared pictures stand in stark contrast to the high-fidelity landscape photographs. I think that juxtaposition helps emphasize the gulf between technological renditions and real-life experiences.

Aside from the technological qualities, I’m also interested in my distance and detachment. I’m an outsider in almost every sense of the word. I’m white, originally from the Midwest, and have gained access to this space because of my affiliation with an academic institution. I immersed myself in this landscape for the better part of 2 years, but at the end of the day, I could always hike back to my car, turn on the a/c and drive back to my apartment in Tucson. I wanted to acknowledge that detachment in my work rather than claim some authority over the space. For as much time as I spent on the border in person, I probably spent twice that amount of time on my laptop looking at pixelated images of it. But being there in person and seeing it on a computer are obviously two very different experiences.

There is a lot of public rhetoric surrounding the border today, but how much can we truly claim to know about this space by looking at it through our screens, or reading about it, or studying and surveilling it from afar? I think it’s a pressing question for all of us, but particularly for those who wield considerable influence over the region.

DG: I am also interested in the percentages of probable identification, which I assume is a product of the remote camera software. This seems to drive home your point on empathy, and if it is possible “in a system that promotes objectivity.” Tell me more about your use of these visuals.

AT: I specifically used the word promotes because true objectivity is slippery. Any system designed or influenced by humans will inevitably feature some form of human subjectivity or bias. You see this all the time now, with discriminatory manifestations of A.I. deployed at border checkpoints and grocery stores and everywhere in between. Many of them claim or promote objectiveness, and that is no exception in the world of scientific research. I do not mean to criticize the researchers I worked with, but I do think it is something that all fields of research need to be mindful of in their methodologies.

As for the percentages, it was one thing to see those mechanics applied to images of deer, and another entirely when applied to humans. In fact, the first human picture I tested was one of myself (I was considered 78% likely to be human). At first I laughed, then frowned, then got sick to my stomach. You start to think of all the ways this technology can be and is being applied, including and especially related to vulnerable populations at the border, in detention centers, etc. That’s where the bias and discrimination come in: in many systems, it learns what (or who) a human is based on the examples provided, so the author of that collection exercises a lot of power. The implications for accurately or inaccurately identifying subjects can be profound, especially if the A.I.’s decision is not questioned.

DG: In your artist statement, you write that our understanding of information produced by these autonomous, remote-sensing devices is clouded—despite being technologically enhanced. What do you think is lost when vision relies too heavily on technology?

AT: Nuance, subtlety, complexity, depth. I think these are all core attributes we use to understand others and our surroundings. It’s what makes us human. Many of those core attributes are being simplified or eliminated for the sake of efficiency and accumulation. How do we account for nuance and complexity when no human is there to read between the lines?

It varies greatly depending on the application. I’m showing you examples of this through the lens of researchers studying wildlife, and the stakes are relatively low. Whether or not A.I. correctly identifies a white-tailed deer will probably not adversely affect someone’s life. But they monitor the same spaces and capture the same footage using the same tools as government agencies and private security firms, so you get a glimpse of what happens when these technologies are pointed at humans.

There are plenty of benefits to these technologies as well. For instance, remote sensing cameras collect information that wildlife researchers would never catch in the field themselves. A.I. will save the them countless hours by sorting through footage and potentially identifying patterns that humans may have missed.

These technologies are very polarizing: people often describe them in either messianic or apocalyptic terms. I see both ends of that spectrum, and the outcome will entirely depend on us and how responsibly we implement these powerful tools.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026