Photographers on Photographers: William Camargo in conversation with Irene Antonia Diane Reece

I can’t remember when I did find Irene Reece’s work, but I know as many new friendships nowadays, it started on Instagram. I may have seen it from a mutual friend of ours being shared on their stories or saw her name on an art exhibition flyer, and as I do with those is spend an hour and explore everyone’s work. I always ended up coming back to her work, dissecting it, looking at it more closely as if I had missed something the first time I saw her work. I find her work like mine to be very personal, she brings us into her family’s history, pushing against the hegemonic stories of Black folx in the United States.

We found similarities in our work and have enjoyed various conversations on our experiences in academia, shared books, and, most importantly, shared our vision to see the change that is needed in photography. Furthermore, Irene’s work deconstructs the canon, installing a Black feminist approach rooted in liberation and freedom, which is currently required. I hope that just as much as I enjoy her work, the Lenscratch audience can as well.

Born and raised in Houston, Texas, Irene Antonia Diana Reece lives and works between the United States and Europe.

She graduated with her B.F.A (2018) in Photography and Digital Media at the University of Houston and M.F.A (2020) at Paris College of Art in Photography and Image-making. She exhibited a solo exhibition in 2017 at Lawndale Art Center in Houston, TX; in collective 2020 XicanX: New Visions curated by Dos Mestizx (Suzy González and Michael Menchaca) at Centro de Artes in San Antonio, Texas. She’s currently exhibiting work for a collective exhibition in 2019-2020 in Paris, Barcelona, Utrecht and exhibiting in collective “Souls of a Perseverant Generation,” at the Community Artists’ Collective in Houston, Texas. Her series Billie-James will be exhibited at the 5th Biennale Internationale de Casablanca in 2021.

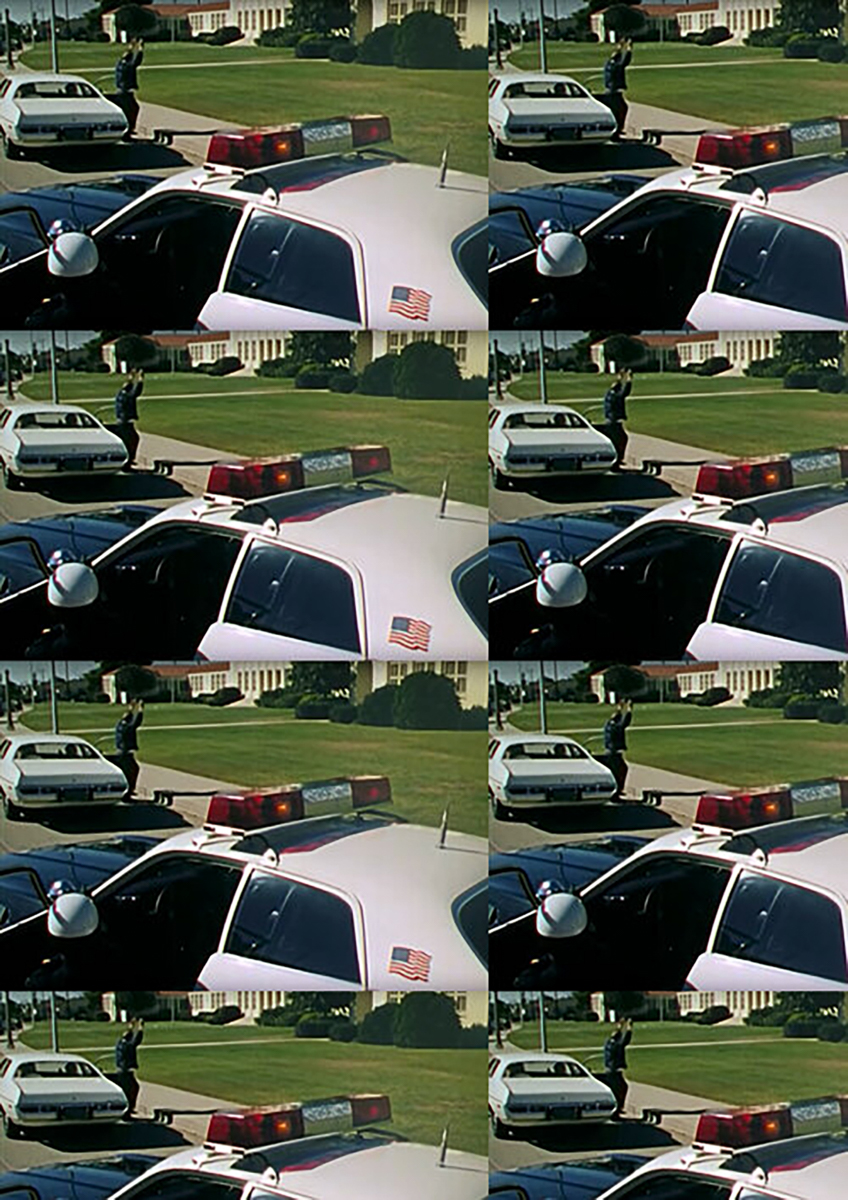

Reece’s is noted for creating installation work that is multifaceted. Her array of photographic works, appropriated films, usage of text, and found objects create an insight towards issues that revolve around racial identity, African diaspora, social injustice, family histories, mental and community health issues. She identifies as a contemporary artist and visual activist. Her recent work questions society’s perspectives on her racial identities and combats the social norms in regards to being a Black Mexican woman living in the United States and Europe. Her work pushes boundaries and forces her viewers to confront issues that are deemed difficult to tackle. Instagram: @reanie_beanie

William Camargo (he/him/they) is a photo-based artist, art educator, community archivist and organizer based in Anaheim, California. He is the founder and curator of Latinx Diaspora Archives, an archive living on Instagram of family photos of the Latinx Diaspora. He is currently serving as the commissioner of Heritage and Culture in Anaheim. A current teaching artist fellow at the Armory Center for the Arts, and recently completed his MFA at Claremont Graduate University. He received his BFA at Cal State Fullerton and an AA in Photography from Fullerton College.

William has held residencies at Project Art, the Chicago Artist Coalition, ACRE, and at LA Summer held at Otis School of Art and Design. He has also participated in the New York Times Portfolio Review, NALAC’s Leadership(2018), and Advocacy(2020) Institutes. He is a current member of Diversify Photo an initiative started to diversify the photography industry. He was awarded the Friedman Grant and J. Sonneman Photography Prize from CGU and has given lectures at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside, Gallery 400(Chicago), University of San Diego, Cal State Long Beach, the Claremont Colleges, USC Roski School of Art, Stanford(upcoming).

Additionally, his work has been shown at the Chicago Cultural Center, Loisaida Center(New York), the University of Indianapolis(IN), Mexican Cultural Center and Cinematic Arts(Los Angeles), Stevenson University(Baltimore), The Cooper Gallery of African and African American Arts at Harvard, Irvine Fine Arts Center, Los Angeles Municipal Gallery, Filter Photo(Chicago), among others. Instagram: @billythecamera

William Camargo: Why photography as part of your artwork?

Irene Reece: I developed a love for photography and image-making based on the process of analog and working with my hands. Growing up with a father whose job was working for art spaces in the education sector and writing art reviews I found myself being submerged into the arts. The appreciation was there but I didn’t necessarily know that I wanted to do it. Once I learned at 18 how to load a camera, develop my own film, and print in a dark room I was immediately hooked. Photography is a very versatile medium that is what I’ve learned throughout the years developing my work. I am enamored with the idea of making work that seem so simple but has a layering of hidden messages and meanings. I am very critical of photography in the sense of how it has created forms of violence towards BIPOC communities. Being that I am a contemporary artist and visual activist it is very important for me to use photography to relay those messages of social injustice not only in our daily lives but in the art community as well. Imagery is a powerful visual aid. You can use it to create rhetoric about your values and what you believe in. It is a form of representation and we see in the past what imagery has done for BIPOC communities. My usage of photography is to try and eliminate the canon and showcase the fluidity of the communities I represent.

WC: You use a lot of archival material, most if of all from your family archives, how is the theme of memory and re-memory important to you?

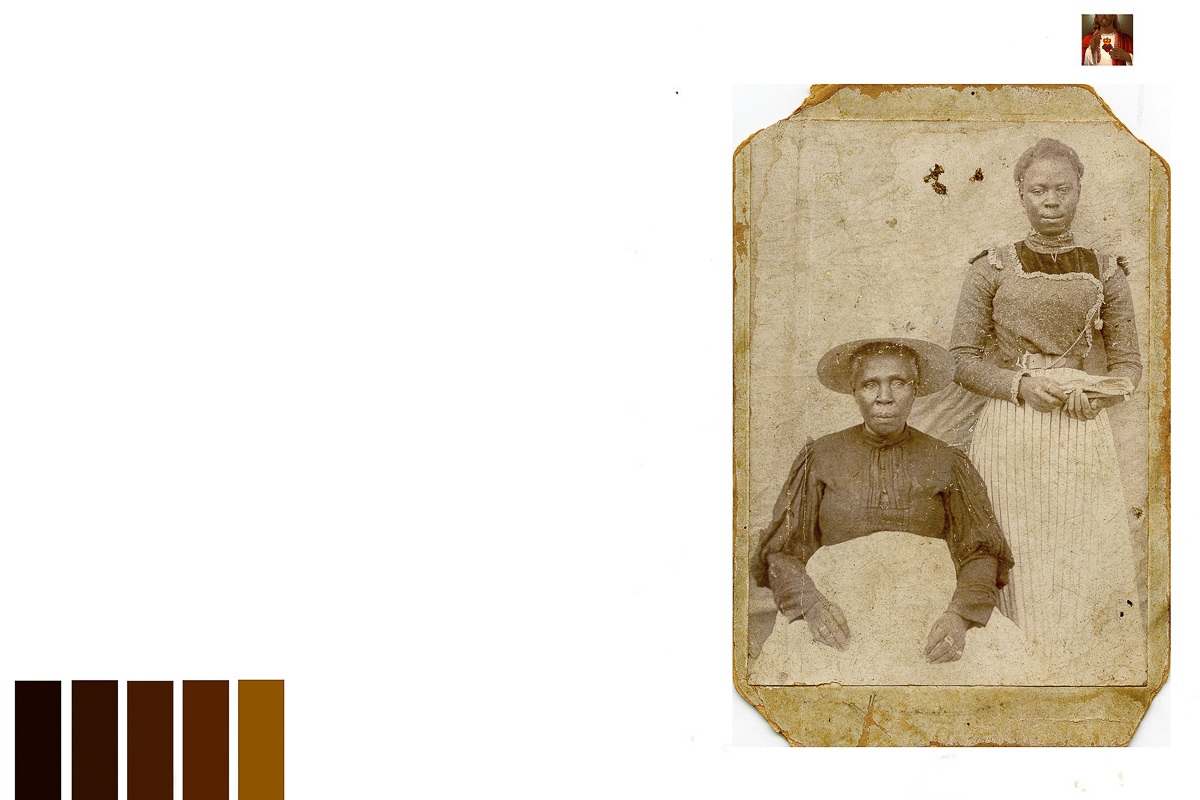

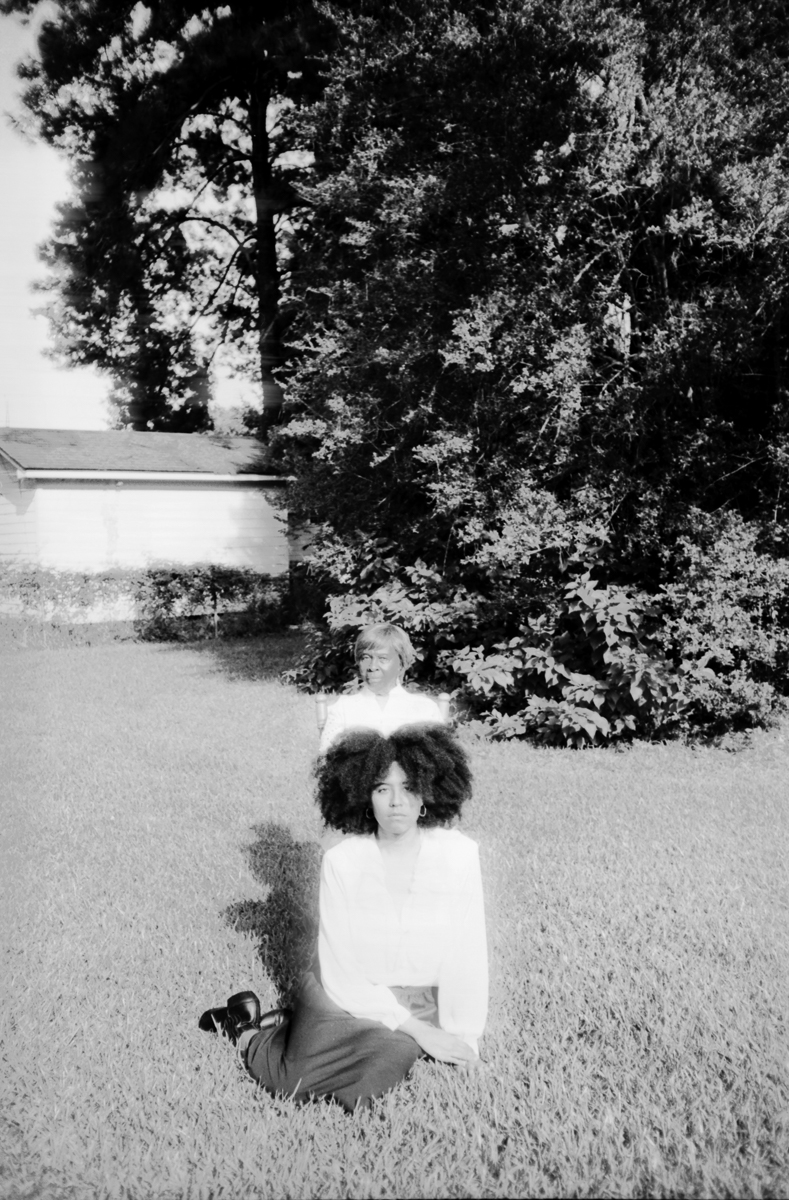

IR: I never thought that a family archive would provoke so much feeling until I was away from home. When I lived in France by myself there were days that I would just look at my photo albums. This brought me great comfort. Reading Tina Campt’s books really provoked the importance of the family archives and what it means to even have those images in my possession. We live in an age were images are created every second but we do not understand the privilege we have to capture our families now. Having photographs from the past, from your family history is a privilege in itself. Do you know how expensive cameras are/were, then having it developed, and then making sure they are protected? I have family members that don’t even have one photograph of themselves when they were children. Could you imagine that? It is almost as if you didn’t even exist. Another method I use is my practice on spirituality. My belief comes from my religious background of death, rituals and the importance of family members belonging. When someone passes on you collect their things that are memories of their past and objects that hold a great significance to you. In that sense you have a piece of their spirit and you are allowing their legacy to live on through those possession you have kept. I use that practice of memory and re-memory in my work with family archives because I don’t want them to be forgotten. When I bring family archives back into circulation there is this powerful presence that they are alive again. Even if I cannot identify majority of the family members, I believe it is still important to acknowledge their existence.

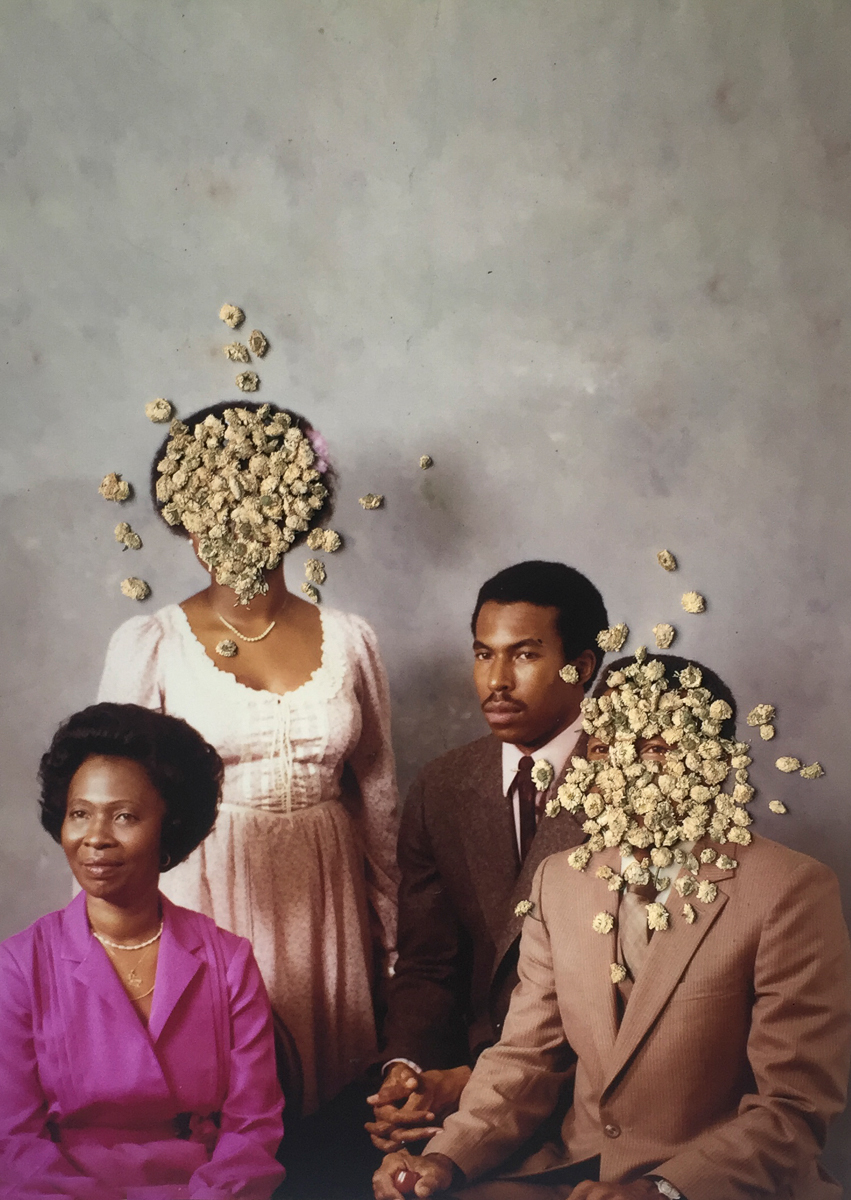

WC: I see that you include objects in your work as well, how did that come about?

IR: The usage of objects is always used in my work. I find it necessary to convey different messages, some hidden, others most obvious but it is to heighten the narratives that are being showcased in the work. With Billie-James you have all these different experiences that happen in the Black community, some you can’t necessarily crack through just an image. I mean you can but for me it just doesn’t feel right.

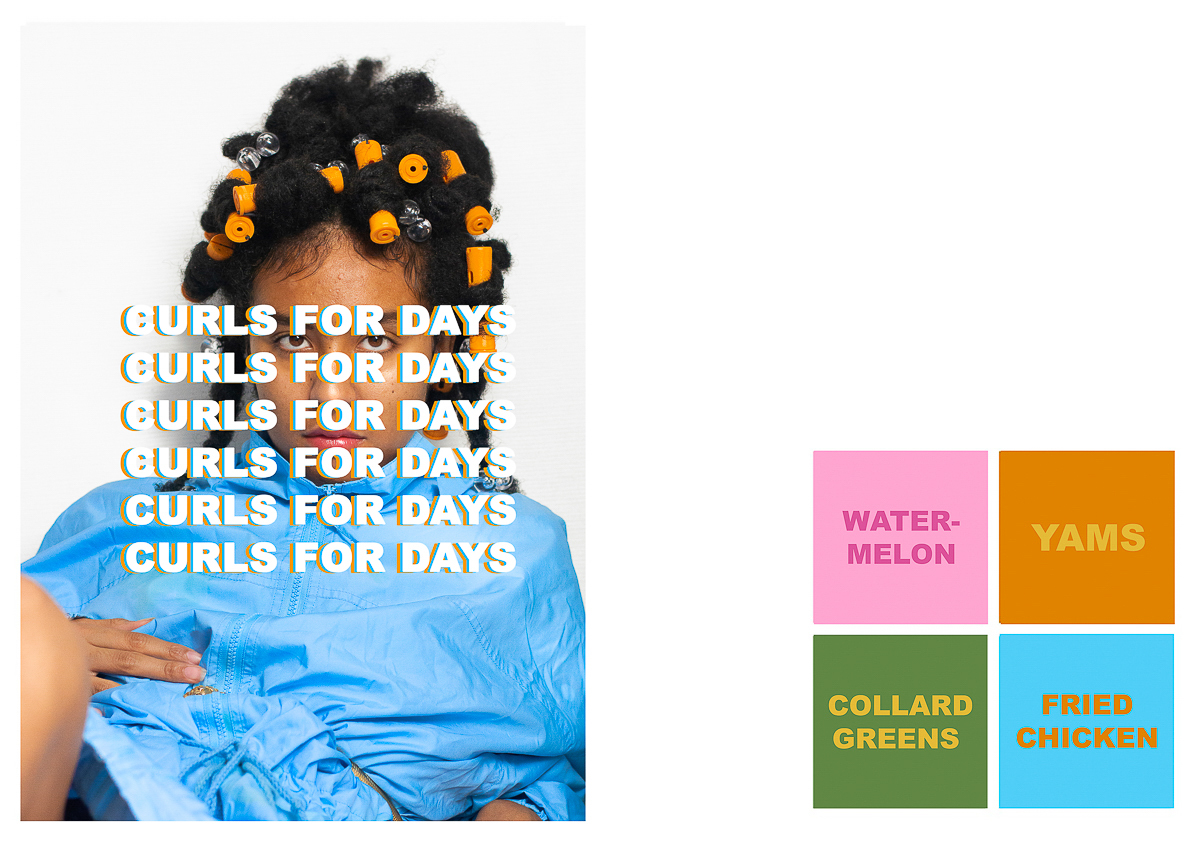

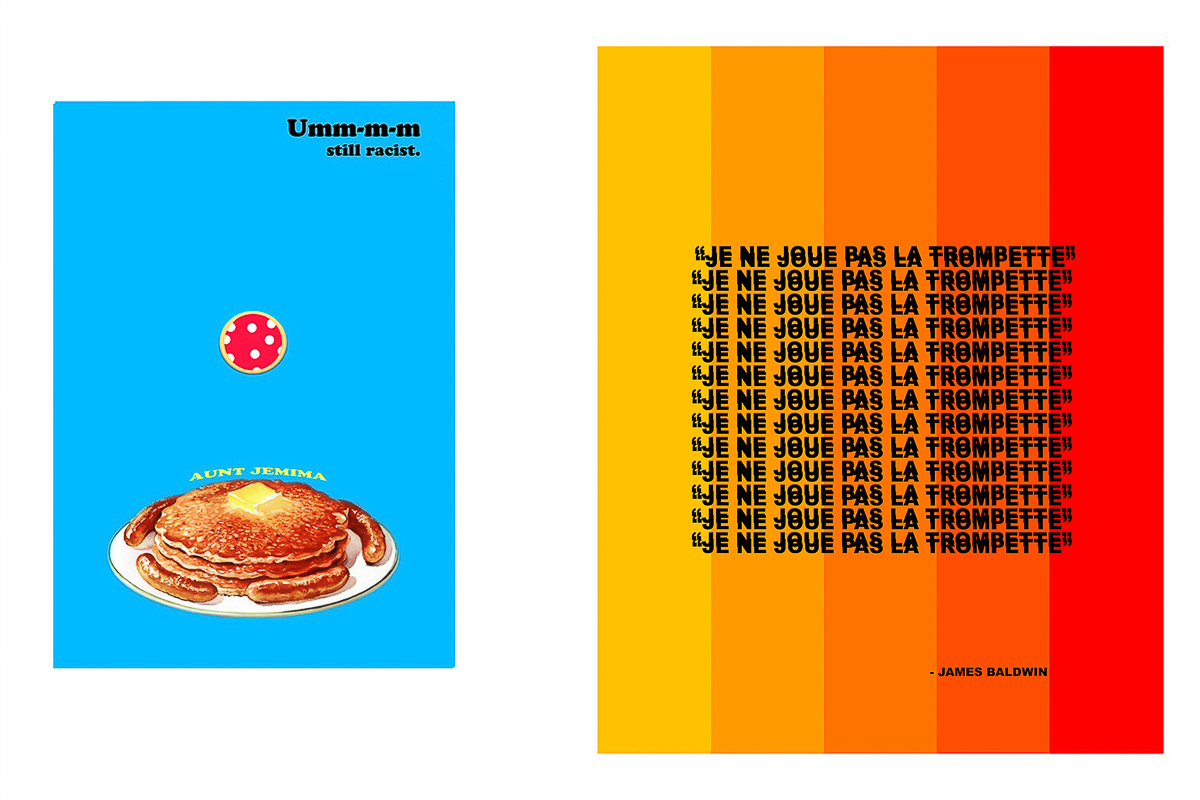

WC: Your use of text is also apparent in your work, how do you see the relations of photo and text work for you?

IR: Some text is made to be a stand-alone piece while others are made to coincide with the photographs. I have a deep relationship to literature and language due to my upbringing. My father is a writer and his mother was a librarian. Everything that has been read to me growing up was based on his upbringing. This reoccurring generational love and support through literature and spoken words has then transferred into my childhood. Growing up in the South you grow up with the Black southern vernacular. A lot of the phrases I grew up saying influenced my work. I even go as far as quoting messages that family members would say to us growing up regarding Black liberation or just plain old fun. Words can have a strong impact just as images can, in both cases you are needing to visually look at both to experience it. By putting text with the images, I am creating a statement about the image or a statement behind the word. Either way the text is part of the root of my forever growing creative tree.

WC: Knowing we have talked about higher education, what do you want to see a change in institutions?

IR: Art institutions to me meaning museums, art galleries, art fairs, non-profit art spaces, and art universities/ art programs. No one is out of the loop. All of these spaces have not done enough for their artists, audiences, and students that represent the BIPOC communities. I am tired of waiting for institutions to make change when it should have happened years ago. The way institutions are being handle when my father was working in these spaces during the 90s are exactly the same now in 2020.

You owe it to us, the artists and the community that are having to endure this discomfort and violence in these institutions. It is really hard for me to answer this civilly. This isn’t a new topic to be researched. It has been done already. We know there is a lack of representation in art institutions in the museums sector and educational sector. It is a homogenous environment where white is dominating the art scene and art spaces. These institutions are no different than other places that are receiving backlash for their lack of representation. We are in the arts and some generalize that we are a progressive job field because it is the arts. That is far from the truth. I would rebuttal and say it is so political.

Having talked to my undergrad university’s art department and my graduate school all you see is a neutral corporate approach. These terms like task force and diversity & inclusion committee are not the only solution. And I truly feel in my heart they believe it is going to work by just brainstorming and nominating student/faculty to solve issues. You can’t approach this in a linear way because it is not. For one these are topics that intersection each other. You can’t fight racism, xenophobia, transphobia, sexism all the same way. They are not the same thing! You can’t just assign an Anti-Racism book for your faculty and then give yourself a pat on the back. You can’t just have a day or week of diversity and inclusion training. It is a daily effort of learning and unlearning things. I am honestly very confused as to why they haven’t hired someone that actually does this for a living? The whole training. Training should include learning about cultural awareness, gender studies, learning of pronouns, unlearning implicit bias, unlearning generalization, unlearning Eurocentric and western views as the primary source of learning and being empathetic. It’s funny. There are all of these actions I am wanting to happen but I know it takes time. I do believe that institutions are not pushing forward and cracking down aggressively towards people that have created any form of violence towards BIPOC. I am wanting to see methodology introduced in the curriculums. We are not taught in art school to be critical of the tools we use or the concepts we create. I want to see intersectionality feminism practices and critical curation and decolonizing the syllabus. I want educational art institutions like the ones I attended to have solidarity for their students versus the famous artists they hired to make their college look good. I want institutions to destigmatize mental health and stop intellectually hazing students.

I have a question for institutions. What is the objective of you creating diversity and inclusion in your spaces? Are your intentions pure? When we talk about diversity and inclusion who is being nominated? Who is doing the majority of the work? Are you making your BIPOC answer all of your questions and solve all your problems for you? Which to me is a form of privilege/white supremacy in itself. I express this due to the fact that you as an institution are not wanting to confront the issues yourself. You are not taking the initiatives to learn and stop these acts of violence on BIPOC communities because you cannot handle the discomfort. Even Though we have experienced all of our lives. Other questions to think about for institutions. Is it benefiting the BIPOC students and faculty or is it causing more harm? I apologize for the multiple questions but I am unapologetic of the statements behind it. If you are hiring or have more representation of BIPOC communities that doesn’t mean you are meeting the status quo. The institution can still harbor forms of white supremacy which then helps the reoccurring cycle that we face in these institutions.

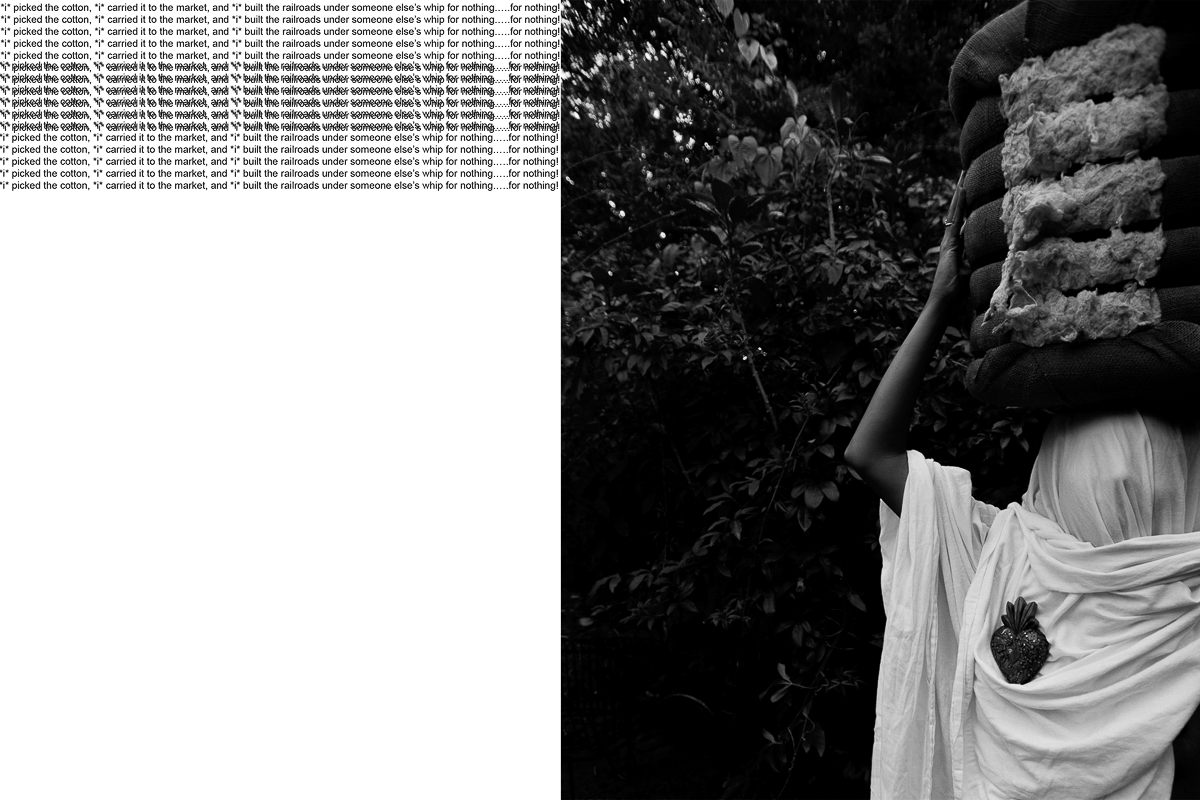

©Irene Antonia Diane Reece, “Home Again Home Again Jiggity-Jag & Where the Story Begins and Ends”, 2019

WC: How was your experience institutions? You can be as blunt as you want.

IR: An institution is still an institution and I felt institutionalized in the spaces I was in. You want to talk about tense and unhealthy environments? Being the only Black Mexican American in your program is so exhausting. Both times during my undergrad years at the School of Art – University of Houston and Paris College of Art I felt I didn’t belong in these spaces. Majority of my professors were White or European and I felt this level of discomfort. You receive praises for work that comes off as universal versus work that is labeled as “political” and if it is labeled political, they will try to generalize/stereotype what your work should represent.

During undergrad, my program was majority BIPOC so I had a tribe. We would talk to each other about our work and that has ultimately become my close community now as a full-time artist. I had issues with the lack of BIPOC faculty. One year we finally had a Black photography teacher sadly he couldn’t teach our program year but I would invite him to our crits and ask for private feedback. It was an amazing outcome having that form of representation in my program.

I have had incidents in graduate school where a professor and administrator called me naïve and ignorant because I wanted to do a project about racism in Paris, because they believed racism doesn’t happen there. Hearing two white males tell me that was sadly not shocking for me but rather an uncomfortable moment. I realized I wasn’t safe. To have white European artists tell you what is and isn’t racism is a form of white supremacy. I grew up in the South of the United States. I have experienced racism and discrimination since I was four years old, I am able to identify the layering forms of covert and overt racism. I had to sit there and prove my experiences, it was daunting. When the faculty and administration didn’t protect me during those events (which happened on numerous occasions), I did feel broken and overwhelmed. I am a lower-income student and I had to make a decision. Do I continue to endure forms of violence? Do I make art that will later help me have a smoother time in graduate school? Just completely assimilate and conform to their way? So, I can keep the connections I have made and not receive forms of retaliation. OR. I call people out, stand my ground, and fight. I stood my ground, slowly at first but I stood it. I took a risk on my career because I had no idea who these faculty members and administrators knew. I felt an obligation and duty to stand up for what I believe in. I come from a long line of family members that were fighters, innovators, and liberators. I come from a long line of Black and Brown excellence. No BIPOC student nor artists should have to bear the weight of calling an institution out when the institution shouldn’t be causing these forms of violence in the first place. I have learned a lot from my time in school. I learned to protect my identities like my ancestors have done, swallow the discomfort, heal and fight for what you believe in.

WC: Whose work are you looking at? And was that reflective of the work your professors were showing you in undergrad and grad school?

IR: Man listen! I am so influenced by a multitude of artists. I will name a few but the list could be at least over one hundred artists that I have admired over the years and have drawn complete inspiration from. I look at Albert Chong, Ellen Gallagher, Eustaquio Neves, Oscar Muñoz, Graciela Itrubide, Willem Boshoff, Frida Kahlo, Sara Blokland, and Carrie Mae Weems just to name a few.

In comparison to the work I was being shown in school it wasn’t the same. The work I was shown throughout my time in undergrad and grad school were photographers and artists that were labeled as the classics. Even the readings and critical writings we were analyzing were majority white authors. These artists and authors whom were majority white/European were always put up on a pedestal. I didn’t understand the push to showcase and talk about them constantly. It really shows the lack of BIPOC artists being taught about in art school and BIPOC just being acknowledge as one of the main influences in the art.

WC: Can you describe your process, maybe specifically with the body of work named Billie James?

IR: I started that project with just a 20-pound cotton bale, some butcher paper, broken mirrors and expired polaroids. I never anticipated it becoming this rich and layered body of work. Billie-James title stems from my influences of growing up listening to jazz and blues. I had always been fond of Billie Holiday the jazz singer and her melancholy tone that became inspiration for the sensibility of the topics that are being displayed in the work. The other influence is James Baldwin’s transcript during 1965 debate against William F. Buckley at Cambridge University. The debate question, is the American Dream at the expense of the American Negro? It really struck a chord with me the things Uncle Jimmy (Baldwin) was saying. The outcry and repetitiveness of the experiences that James Baldwin faced was of course no different to my father a Black man. To then be able to find connection of my own encounters with racism as an adult that had been elevated ever since I was a child, made me create this work. I picked through the archives that I had been scanning with the mixture of text, video, and objects to create a body of work that showcased the narrative of Black people have always been great y’all just been sleeping and y’all stay sleeping on what we go through as Black people living in America.

WC: Do you see the state of photography as something that needs to change and how can the future of photography look like?

IR: There is always room to grow and learn, for nothing is ever perfect. Different forms of methodology revolving around photography and image-making needs to be introduced more. I believe if you own a camera, you call yourself a photographer, image-maker, photo-journalist, etc. You are needing to still be critical of the camera. The camera has a long history as being a tool of violence towards BIPOC communities. I truly believe people are needing to be more aware of the impact that the camera has on others. Books such as The Civil Contract of Photography by Ariella Azoulay, Art on My Mind by bell hooks, Image Matters and Listening to Images by Tina Campt to just name a few. There’s more theory and books on the arts and photography besides John Berger and Susan Sontag. I felt those two authors in particular were shoved down our throats. I do believe it is important to read some of their work but to have majority white based artists and authors as your primary source is a reflection of what you deem as art. And frankly white artists and authors are obviously not the only ones taking on this job field. Yet they are being represented, taught, and written about the most. I believe photography has always evolved and the industry in general is changing. I think the change has been needing to start a long time ago. We are needing the representation of BIPOC in all sectors, cultural awareness, and eliminating the canon from the arts in general.

WC: Was there a difference between how your audience reacted to your work in Europe vs the states?

IR: In the United States I hadn’t shown my social injustice work before. I was doing work on mental illness and community health so it wasn’t questioning the presence of whiteness in society (or so they thought). Versus in Europe they were the first to engage with this body of work. I had mix feelings being directed towards me because some people were for the work and others felt personally attacked. I felt full gratitude when I had to speak about my work in Utrecht, Netherlands and all the BIPOC students and white students were wanting to talk to me more about my work. We even had a full-on discussion about race, colorism, and police brutality; that truly was the most support I have received in Europe. So far in the States I have felt an abundance amount of love and support. I am able to connect with stranger about my work on a personal level. I am hoping my work continues to do that because that is the most important thing for me as an artist to be impactful and inspire others.

WC: What is in the future for the amazing Irene?

Ha-ha “amazing”. (sorry I snorted). I am supposed to be going back to Europe in 2021 for a few exhibitions and to Casablanca, Morocco for the Casablanca Biennale but we will see. As of right now I am stuck in the States due to COVID-19. I am seeking either residencies with art institutions and or work in an art program at a university. We shall see due to the hiring freezes happening all around the world. I want to publish a few of my art books and make them accessible to everyone especially future Black and Brown artists. In regards to my next goals or plans. I am wanting to showcase work in the public arts in Houston and honestly all over Texas. I got to share whole lotta love to H-town and my fellow Texans. I missed my home. I am also hoping to do more community-based work in the neighborhoods I grew up around which are neighborhoods that do get overlooked in revolving around the arts. There are so many things in store for me and I can’t share all but I am excited. Looking forward to the future.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026