Troy Colby: The Fragility of Fatherhood

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series The Fragility of Fatherhood by Troy Colby.

Troy Colby was born in rural Kansas in 1975 and currently lives in Lawrence, Kansas. His work and research explores the delicate balance of family, fatherhood and the outcome of the family photo album. Motivated by intellectual and psychological inquiry of these intimate topics, Troy photographs his own family as a means of understanding the emotional qualities that come along with fatherhood. It has become his means of understanding while creating an honest interpretation of the idealized family album.

He received his BFA from the Academy of Art University in 2015 and his MFA in 2019. His work has been seen in Black and White Magazine, Lenscratch, Feature Shoot, Plates to Pixels, The Photo Review, Fraction Magazine, Der Greif and FotoRoom.

The Fragility of Fatherhood

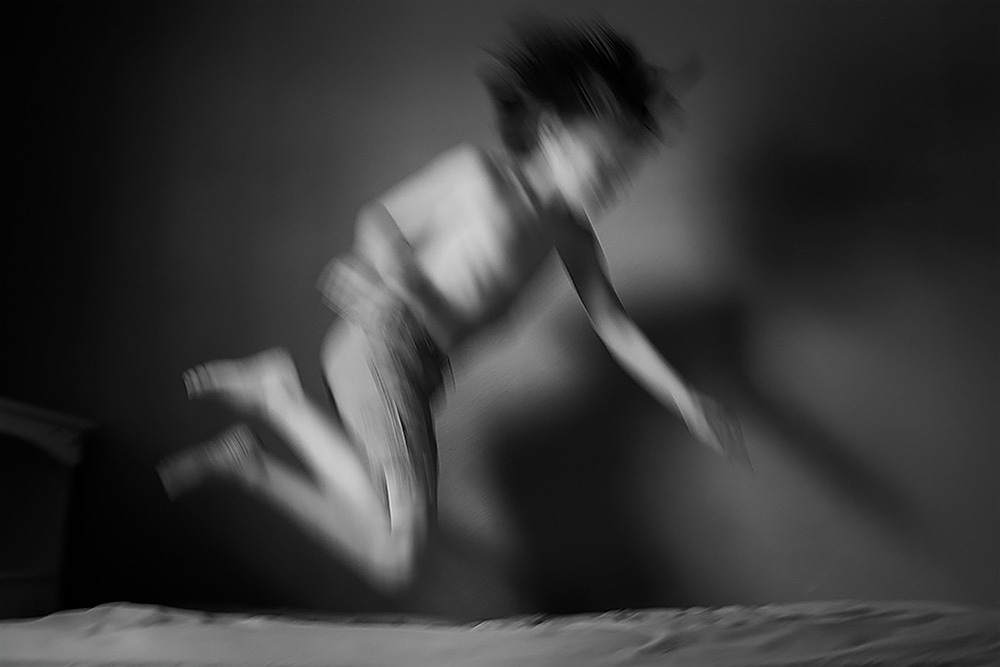

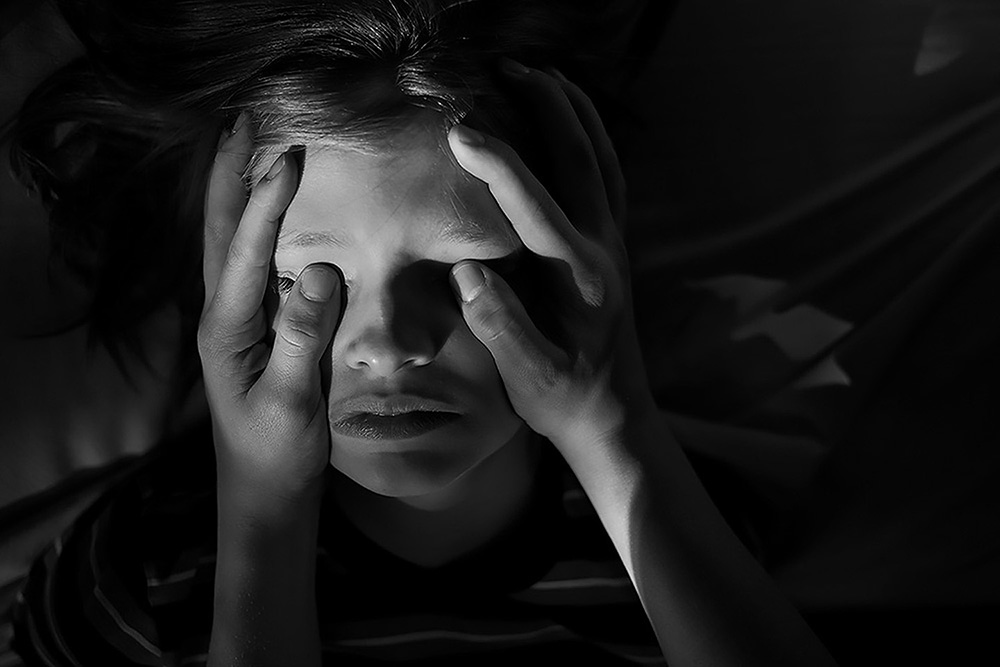

Hold my hand and hold your breath. I am learning as I pretend to know what I am doing. I am so tired and worry more about you than myself. I am restless in this domesticated life. I long for more for you and myself. Things seemed easy when it was only the pitter-patter of your little feet. Life can be so unkind.

I see the way the light hits your face as you cry out for warmth, I see how it hits your face and shows the lines of wisdom, through the good and the bad. We are the quiet and unspoken, yet we scream the loudest.

Rest your tired eyes. I will cover you in warmth. We will move past this and carve out our own light against the darkest skies. As the words, Are you Okay fade from our lives.

Daniel George: When did you begin photographing your children? Did you have projects in mind from the get-go? Or did that come later?

Troy Colby: I never set out to photograph my children or wife. It was something that came out of necessity. I went back to school late in life. At first, I was studying to be a film major. That quickly shifted once I forgot how much I loved using a camera to produce stills. Living in rural Kansas at the time, I didn’t have access to models and I was bored with the landscape around me. So I made do with what I had and that was a young family that was willing to help. In my earlier work, it would start off with an idea. Though over time I became sick of struggling to have that “one” idea to build a project around. When I let go of that notion I started seeing what was always in front of me. Now projects come together after shooting for long periods of time and visually reading the photographs as a group.

DG: How would you describe this series within the evolution of your collective bodies of work that deal with themes regarding family?

TC: This series takes place over the course of 5 years. I am still shooting but things feel different now. I am different and my kids are different. Our relationships have change as we all age. The series is where I first learned to be vulnerable and started to understand my role as a father, husband, and caregiver. I try my best to be a good person and I am brutely honest and loyal. Raising a family is hard and I don’t think that this is talked about enough. We are shown this idealistic American dream but often skate around the struggles we all face. This work fits into the evolution of life and my work by just the sheer nature of timing. We had just recently moved, my boys were turning into teens/ young men, my daughter set out on her own, I was in grad school as a stay at home parent, trying to find my own way in life still. It was in ways a perfect intersection of multiple things that set this work up to happen organically. In reading of the recent work I’ve made and where we are in life. The work is changing but at its core, it is still very much centered around family.

DG: Your statement, “I am learning as I pretend to know what I am doing,” stood out to me, as it is a realization that I had when I became a father several years ago—that in the beginning, parents really have no idea what they’re doing. And there is constant unknown as children develop and change throughout their stages of life. Did you find that creating this work allowed you to more closely examine your parental practices? Did anything change as a result?

TC: Absolutely! When I first met my wife she had a child who was one. So I have been a parent since I was 19 in some fashion. When we had another child, I wanted to be the best parent I could be. I attended parenting classes and read books on parenting. I did as they suggested. Only to find out that these methods don’t work for everyone. In fact, some of those prescribed theories backfired in our family unit. In the end, I really want to be the best-engaged dad that I could be. This also put a lot stress on my shoulders in trying to do so. I often fall short of meeting that mark that I had set up. I still don’t have it all figured out and often make mistakes.

Photographing my family gives me balance and allows for things to feel okay in the world. Even though that is not what I show in the work at times. It is in sitting back and viewing the images where I find a place of reflection and compassion. Photography becomes a tool to help balance my internal struggles. Which helps me function and handle the emotions of the day to day and being a dad.

DG: I am interested in hearing more about your process. I have a hard time photographing my kids, because I am reluctant to filter my experiences with them. What did your collaboration look like? And how did it have an effect on your relationship with your children?

TC: When the children were young, it was all about bribery for the most part. Most of the work in the past 5 years has been within the home and around the house. So the collaboration was generally pretty quick. I would call it painless but sometimes five minutes for a young boy is five minutes too long. They were always willing to help or hold still for just a few minutes longer while doing something. Now they are older and these moments are fading and becoming harder. I feel this tends to happen once they hit those teenage years.

With my youngest and middle son, they honestly don’t know anything different. They have grown up under the lens. So I don’t know what the effect will be in the long run. It is definitely something I consider and even wrestle with. They are aware of the work and I respect their input and opinions. In their eyes, its just something that dad does. I feel like the process and collaboration has always allowed us to spend time together. The moments leading up to or after the photograph, I cherish. I can only hope that they can look back at some point at all of this work and view it as their family photo album.

DG: While viewing your images, I was reminded of themes including the passage of time and growth/development—which are often at the forefront of projects dealing with kids. You allude to this by mentioning the bygone sounds of scampering feet. In what ways do you see this series contributing to the broader dialogue and tradition of parents involving their children in their work?

TC: That’s an amazing question and one I have never considered. I love a great amount of work that tackles the subject of family. It’s a rabbit hole that I am not afraid to go down. It can be a hard subject to tackle versus what some tend to believe. In thinking of the tradition, history, and even contemporary photographers that work with their family. I don’t really view myself as anything new. Gowin photographed Edith and his children for years. Mann showed her children in spectacular postures and scenes. Friedlander photographed his family in everyday situations for years. There are countless others and that list grows daily.

For me, I want to show what we don’t see on social media or in the traditional family album. I want to show those struggles we all have but are afraid to admit. I am showing my honest feelings from a viewpoint of a father that is really trying to do his best, but also understands how cruel the world is. In showing this work, I hope that it can open up a dialog about parenting struggles and challenges. With hopes that we can move past this idealized family image that has become ingrained into our minds over the years.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024