Julianna Foster: Geographical Lore

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Geographical Lore by Julianna Foster.

Julianna Foster is currently an assistant professor in the Photography program at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. She received a BFA in Design from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (2001) and an MFA in Book Arts + Printmaking from the University of the Arts (2006). Foster was a 2014 artist in residence at the Philadelphia Photo Art, 2016/2017 finalist at the Center for Emerging Visual Artists in Philadelphia, 2017/2018 selected as a Community Supported Artist, a project organized by Grizzly Grizzly Gallery and self-published the book, lone hunter. In 2018, her work and two interviews with photographers was featured in the publication Constructed: The Contemporary History of the Constructed Image in Photography since 1990 published by Routledge and was selected for the exhibition, The Truth in Disguise Geste Paris, France during Paris Photo as well as work in group exhibitions at Filter Photo in Chicago and Medium Photo in San Diego (2019/2020).

Other projects/publications include work in magazines Conveyor, Proof, Cleaver, Good Game, and Shots Journal for Black and White Photography. She has exhibited work nationally and internationally, in private collections across the country and Foster has collaborated with various artists on projects that include creating artist multiples, artist books and series of photographs and video.

Julianna is represented by PARISTEXASLA.

Geographical Lore

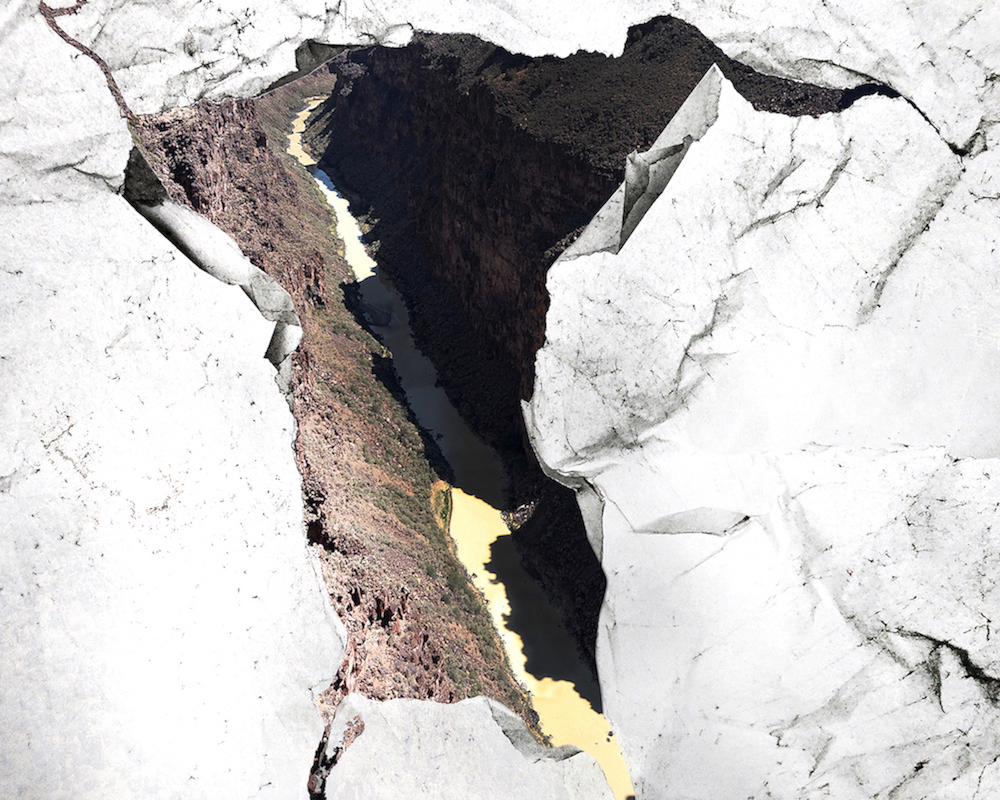

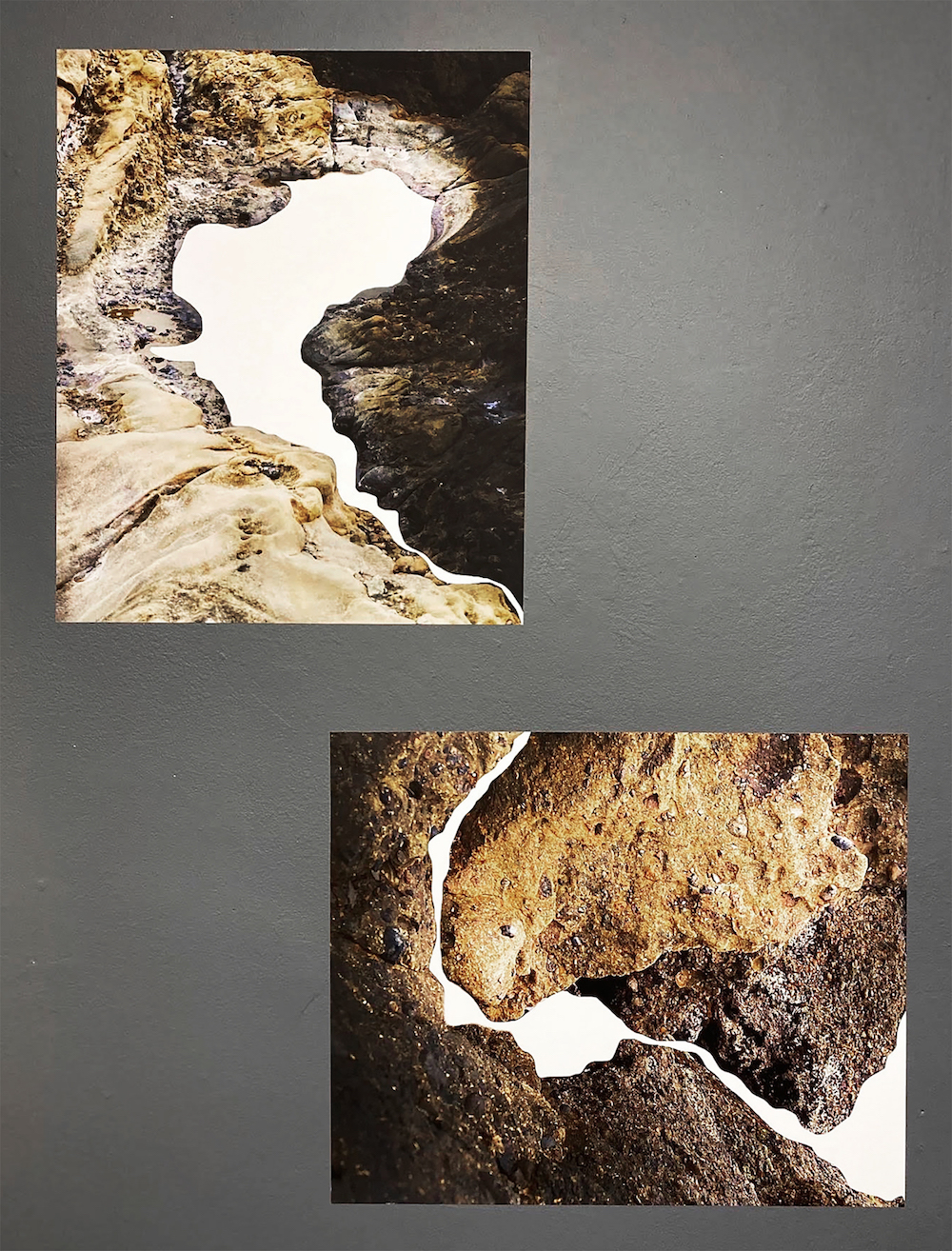

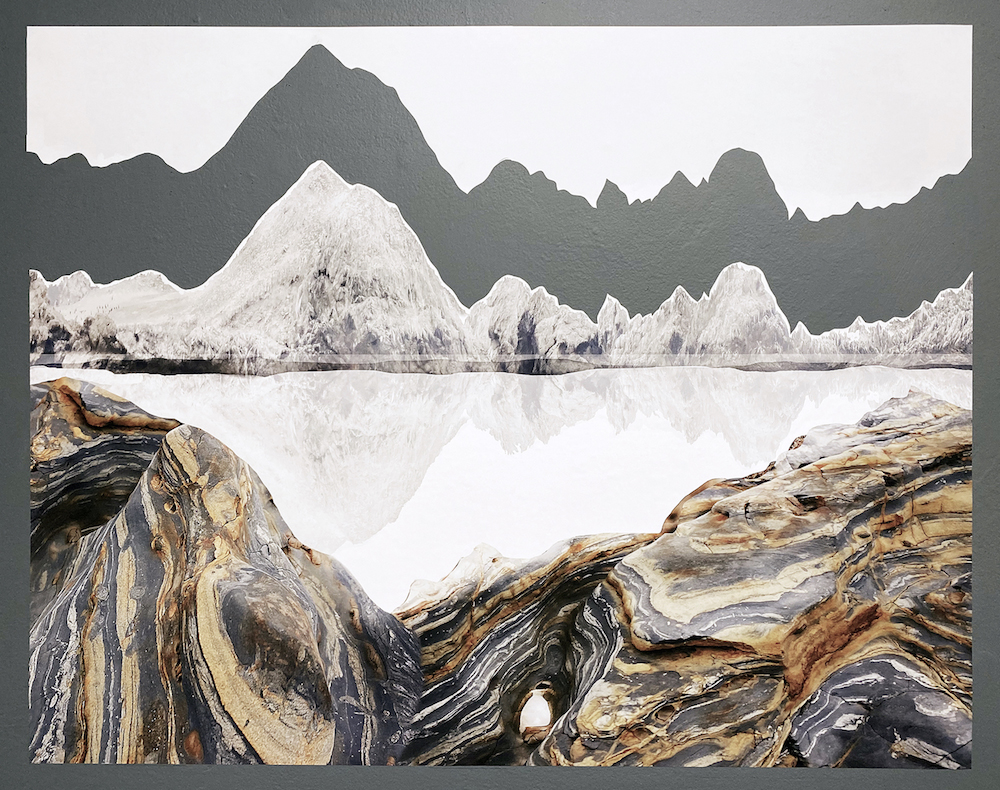

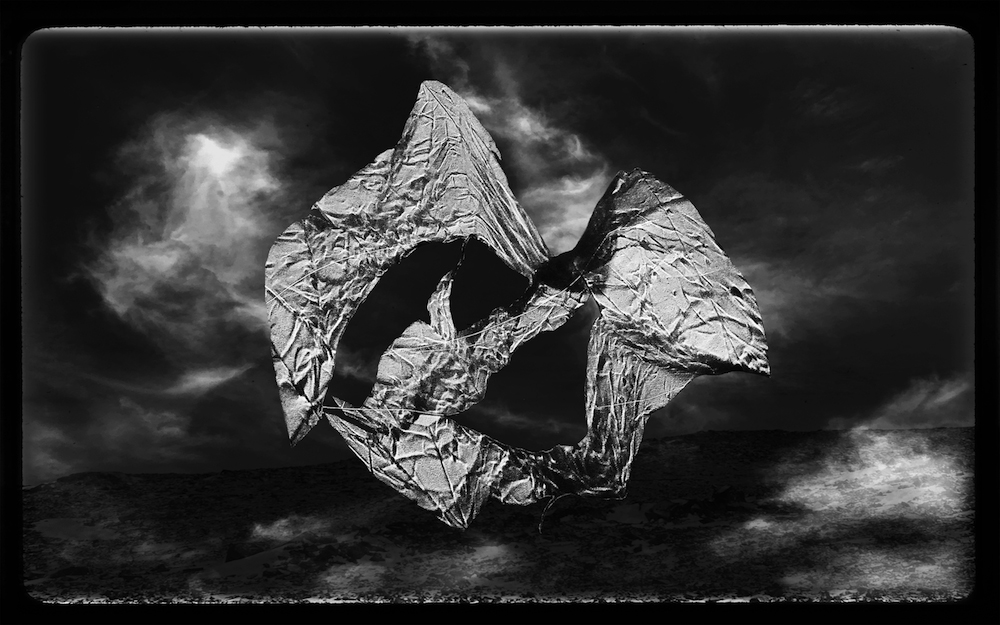

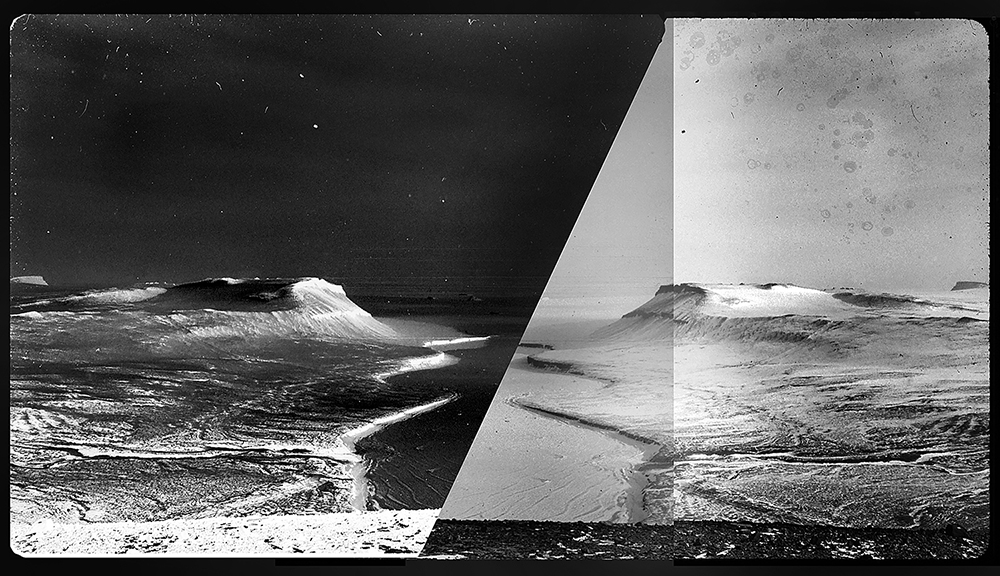

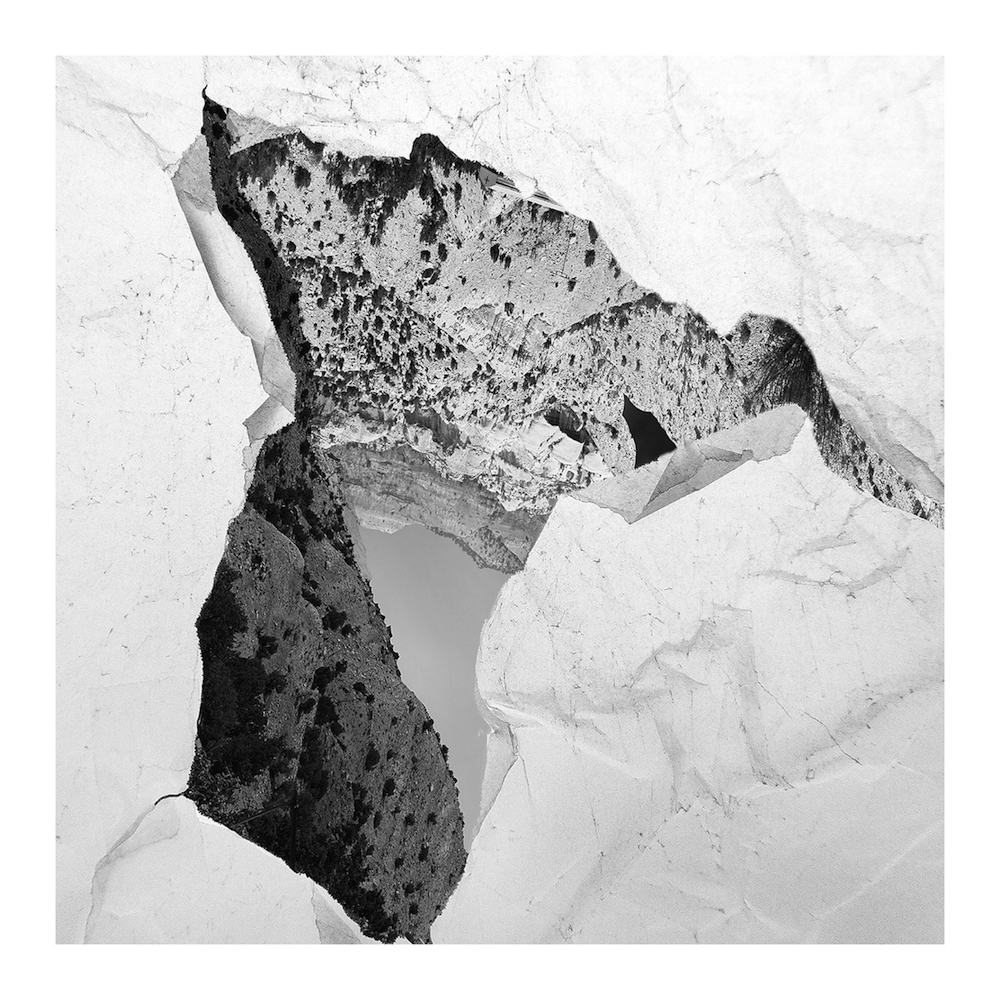

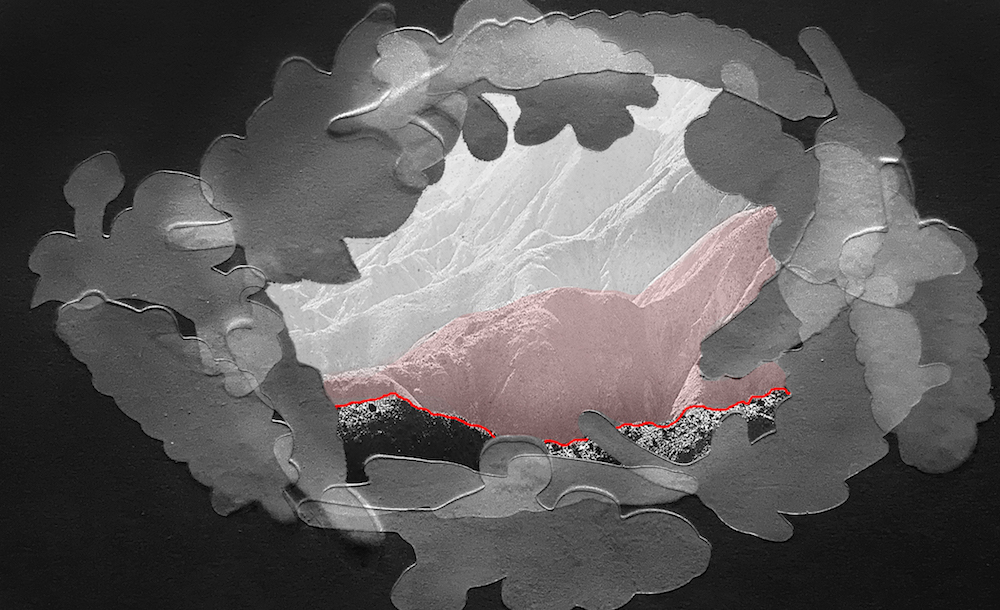

My series, Geographical Lore, is a selection of photographic works that consider ways in which the natural world can be represented particularly within landscapes like forests, mountain ranges and desert terrain where I have recently traveled in California, New Mexico and Nevada as well as areas along the east coast of the US. The impetus for this work comes from my interests in natural reserves, protected lands, wilderness areas and the photographic documentation of the ever-changing diverse geography within and between these locations. My camera as a recording device, I am looking for complexities of both stability and change that occurs over time in the natural world. For instance, low and high tide zones, tidal pools, forest ecology, geologic processes, and astrological explorations. By using the photograph as source material, it creates another way of understanding the subject and allows for an imagined space to expand upon. Through this work I experiment with ideas of abstraction and representation, manipulation, constructing/deconstructing images of these documented spaces/places. And explore how environments function and evolve, at times depicting a façade or fabricated reality that examines spatial relationships, scale shifts, and materiality/structure.

The series consists of a combination of two-dimensional images like framed photographs, broadsides, light-boxes and three-dimensional objects such as cut and manipulated photographs and artist books. They combine photographic images of both the natural world and hand-made, assembled environments. The deliberate blend of the fabricated and the “real” image play with ideas of memory and representation.

Daniel George: Much of the work you have created over the years is landscape based. What interests you in the natural world—to the extent that it has become central to your creative practice?

Julianna Foster: I’ve been thinking about this recently, mainly because of our current restrictions due to COVID. Whether my intrigue with this subject matter stems from physically being present in the landscape, how I respond to & feel within these spaces or more from the representation of these areas, how I imagine them to exist in the world, regardless if I’m present or not. Either way, I assume it comes from my desire to connect on some level, in both a tangible, physical way and/or a fantastical imagined way. I live in South Philly, so the idea of looking outside of my everyday experiences also comes into play. This is reflected in my influences like time lapse footage of natural landscapes and cities in filmsKoyaanisqatsi or Micro Cosmos and the Planet Earth series. Physical Geography, micro systems, habits in nature of change and stability, succession over an extensive amount of time (mountain ranges, sandstone cliffs, desert) and in shorter intervals (coastal bays, rivers) tend to grab my attention. I guess this fascination with the natural world keeps me searching for something, wanderlust. ‘I am a willow of the wilderness, loving the wind that bent me’ (Emerson)

DG: In traditional landscape photography, one must physically be in a scene in order to create an image. I am fascinated that your process entails using a photograph as source material, and creating an imagined space that is physical—as if you are creating a new thing/scene for a person to experience in person. So, while the viewer wasn’t “there” originally, you brought them to a new “there.” I hope that makes sense. Why is it important that these pieces have a physical presence beyond two-dimensions?

JF: I admire traditional landscape photography. And the challenges of documenting such grandeur. Personal experiences like nights spent in the desert with amazing views of the constellations get me jazzed. And exploring locations ranging from wetlands to old growth forests and the geological wonder of Arches and Zion National Park in Utah, Red Rock Canyon, Nevada, and the Sangre de Cristo Range have been highly influential as source material for the work, as both a document and object. I wouldn’t categorize myself as an avid traveler or adventurer (although I’ve had a few river adventures and can make a mean cup of cowboy coffee in the woods!), but I find that photographing these environments provides lots of material to work with/from once back in the studio, plus it generally brings me joy to be there. In some ways, the act of documenting these places is related to preservation. The physical presence beyond 2-D comes from my background with experimental analog photography using liquid light on different surfaces, creating books/printed material and the need to work with my hands as I mimic, on a small scale, some of these landforms.

DG: While creating the “source material,” are you thinking about how it might evolve into a finished piece? Or does that response/realization come later? Could you walk us through that process?

JF: I don’t necessarily consider the finished work at the onset however the progression is interesting and sometimes perplexing to me, it tends to follow a non-linear path, resembling a rhizome. I keep an active sketch book with ideas that functions as a map, it looks like root systems with small drawings/ images/words that track my process. In the studio, as a response to the representational images, at times I move towards abstraction by altering or manipulating the image (cutting, layering, adding different materials) constructing/deconstructing (hand- made assembled environments) lighting the scene then re-photographing the assemblages/ photo sculptures to create new invented landforms/ landscapes. Could these depict the landscape 1000 years from now? This feels like another type of preservation. My interests in photo/object relationships, installation work and artist books have often provided me with various ways to disseminate my ideas into physical form. Within my studio process, I rely on iterations, experimentation and sensitively to materials/presentation to guide me, I post these explorations (many only live at the experimental stage) on my instagram (@jules_foster). My most recent series, Geographical Lore consists of work that explores the blend of memory and representation, fabricated and reality, a portal of sorts, leading you into another dimension, at times visually apparent and others, more symbolically. Well, at least that’s how I imagine it to be.

DG: I am curious about the landscapes that you chose to visit and photograph—in the West and on the East Coast. What significance do these specific places have to the project?

JF: I grew up on the east coast in North Carolina and currently reside in Philadelphia. I lived in the NC mountains and spent time on the Atlantic coast before moving north. In past work the focus was on east coast locations. My series, Swell, depicts an event that allegedly occurred many years ago in a small coastal town after a storm on the Atlantic coast. The series operates on several levels to recount the stories told by witnesses of what happened through a series of photographs, artist book and newsprint multiples that questioned issues related to climate change, human impact on the environment, dystopia vs utopia. Swell incorporated archived images of seascapes and barrier islands in NC and MD.

Currently, due to the pandemic my family and I retreat to nature as often as we can. I get the best of both worlds, hanging with my crew and photographing what we discover on our excursions, young kids see things in the world adults miss, it’s magical to observe and share this experience. I believe that has an impact on the way I recognize the world around me and how it resonates in the work. We don’t venture too far these days but have plans to when restrictions lift and it’s safe. Western landscape has a different ecological footprint than the east coast in wetlands, waterways, coastal bays within a hundred miles of desert terrain and primeval forests. The history of place opens up a unique perspective on the magnitude of the natural world, the wonder, there is always more to discovery.

DG: For me, the title of you project suggests that it is important to learn from the environment—through study and consideration of its history and processes. Your approach to inform the viewer is through abstracted and fabricated representation. What do you feel this work teaches us about the natural world? What did you learn while making it?

JF: The title of my project, Geographical Lore, is a selection of photographs, broadsides, artist books, publications and photo objects that considers ways in which the natural world can be interpreted and represented. ‘Lore’ refers to folklore and myths that align with these invented landscapes. Elements of storytelling have often been at the heart of my work and the deliberate blend of abstract / representational work in this series provides an opportunity for a narrative to unfold. Research is definitely a part of the process, although I don’t work in the same vein as a documentarian so that process offers different outcomes. It’s tricky to pinpoint specific traits that work should offer or teach the viewer, that may be left for you to decide. Filmmaker, Andrei Tarkovsky said in his book, Sculpting in Time “A book read by a thousand different people is a thousand different books.” My intention is for it to invoke curiosity, an allure, taking you on a journey even if for a minute or two. Lately, I’ve noticed that while in the studio, I learn most from small gestures, these gestures hold potential. At least I hope they do, I’ll have to let you know!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025