Ohemaa Dixon: Tanpa Izin

Lands are travelled. Traversing a place we as individuals don’t call home has become an all too casual endeavour. Rarely do we find ourselves facing the reality of what it means to go to a place that is rooted in histories and peoples and ideologies that are not ours. In this way many times a trip or vacation is a form of intrusion and an expression of privilege. The industry of travel is a billion dollar enterprise and is not propagated with responsibility. In the pages of Ohemaa Dixon’s Tanpa Izin a different kind of exploration exists. Rooted in the leaves of Indonesian forests Dixon sets out on a different sort of trip. One rooted in contemplation and reflection. A journey epitomized by views from the back of a motorbike.

Through Dixon we see a view of Bali that is converse to what has become a filter through which most think of this place. The verder in these pictures form a more quiet veneration and thoughtful growth. The pictures are a passing, a breath, a kind of contemplation that allows more mindful interpretations because they are not poised and predetermined. The pictures of Tanpa Izin are professed in forms of confession. They assert that sometimes it’s best to see a place for what it is, and what a place is, more times than not, is not ours. We cannot take, we cannot own, we have no right to it, but we can appreciate how it has grown and what it’s history provides. Dixon leaves an impression, one that provides a reflection of a place. The things inside these photographs will change and continue to form. How we think about them will echo such results if we allow them the space and dialogue they need.

Ohemaa Dixon (1998) is a photographer located in the NY area. She received her BFA in Art Photography from Syracuse University. Her artistic work focuses on capturing moments of the black experience and black feminine narrative through the mechanisms of Afro-futurist thought and the archive. She works interdisciplinarily. IG @obscuralibra

Efrem Zelony-Mindell: I’m going to start Ohemaa by saying I am SO excited to have a copy of Tanpa Izin in my hands! We’ve spoken about it some previously and the passion and care that you speak on the work with I see you’ve put not only into the pictures, but in designing and considering the book. I guess what I’m saying is, congratulations!

This is an expected start, but it’s never a bad idea to start from the start don’t you think? Give us a little background on Tanpa Izin, the pictures, and what we’re looking at when we finally get our hands on a copy of it.

Ohemaa Dixon: Tanpa Izin is Bahasa Indonesia for “without permission.” The phrase started out as meaning one thing and developed into multiple others over the past year. The work are photographs that I took during my time in Indonesia *mostly* on the back of a motorbike. So that summer I was traveling a bunch throughout Europe but primarily I lived and worked in France.. I was doing some research and some writing on black art collection in post-colonial states, and during that time a lot of thoughts and ideas on this project came to light from various experiences I was having there. Those ideas being: otherness, the ways western people travel, the effect of documenting others, and the effects we leave on places we travel too. When I started to look at the genre of travel photography within that lens as I was preparing to go to Bali and during my time there, is where a lot of things began to come full circle.I approached the idea of going to Bali differently than what I would presume a lot of people do. I think because I have relative experiences of what it’s like to be an “other” from a place Western people are interested in going to. Most people have an idealized view of the island, which I think is very prevalent when you go there. I was highly distrubed by the prevalence of Instagram culture that I saw there; things like “Instagram Tour of a Holy Temple” and that’s when I really began to feel bolstered to make work looking at something alternatively and create a critique of sorts.

Zelony-Mindell: Reading your response I’m struck by a few things, but let’s go in a slightly different direction for a moment. I’m going to back up because your intrigue into how photography is used is interesting as it sounds like the initial inspiration of this body of work. How did photography start for you? What intrigued you about the camera and its uses?

Dixon: I was surrounded by photography from a young age. Someone close to my family, at the time, always had a camera and that’s where I first was introduced. I’ve always been inclined towards art and also voicing my thoughts and having discussion. To be quite honest I’m quite terrible at painting so when it came to how I wanted to voice my thoughts photography was my only option as funny as that sounds. Beyond that, I began to mature my views on that during my BFA program at Syracuse. I’m also very interested in critical theory however, I realized not everyone was as invigorated by reading the Cyborg Manifesto by Haraway as I was. That being said I’ve always been intrigued that versus other mediums photography is quite literally a reflection. Through that reflection we are able to literally see ourselves and what we see versus depictions. That literal translation and the conversations it opens up are boundless and truly unique. Most of my work revolves around critical theory actually; it will start with a text I read and thoughts I’m having and I use my work as a way to visually represent ideas and engage conversations those ways. People love to talk about images.

Zelony-Mindell: A reflection! Hmmm, maybe it’s just me, but I really love that as the mirror in some cameras is something that feels taken for granted. A picture is mechanically literally a reflection and it’s interesting how that reflection materializes as an image that forms and functions differently than when a person stands in front of a mirror. A reflection also brings up something I’m always fascinated by in photography which is, truth. I think it’s very easy to see a picture as truth and a reflection is an interesting word in pondering a truth, the truth. The camera is a crafty thing in that way as its power is in the hands of the photographer and that individual’s privilege plays into things. A reflection becomes complicated in thinking about a finished print and the journey it takes to get on the wall.

With all that said I’m curious how you see these relationships of reflections and photographs and truth. Do they meet? Is this debate all just semantics? Where are your discomforts when you’re making your work and does that play into this concept of reflection?

Dixon: Well I mean I should also say there’s always nuances in today’s world of modern photography with things like photoshop and such we are in fact making digital paintings. I work in both manners and enjoy both processes and what the mechanisms of both are able to depict. In a sense it is semantics. I think I don’t seek to necessarily represent direct truth more so represent truths unseen in the theories of utopias that reveal themselves to me. Utopia is thought as a magical land oftentimes in our head when we hear the word. To me a utopia is any space unseen that allows something to exist in a new way, not better just new. A utopia could be a way of thinking, for me most often they are. My work a lot of times is focused on representing and revealing what those utopias look like to me. There’s a wonderful lecture by Murray Bookchin on this that I’ve been reflecting on a lot.

Zelony-Mindell: I’m going to press you a bit here. Could you keep going with this thought regarding the relationship between the unseen, utopia, and newness? What is it about Bookchin’s lecture that has you reflecting on it?

Dixon: Bookchin talks about the difference between utopia and futurism and it strikes me because of his following thoughts on futurism. He talks about not extending the present into the future as futurism suggests. This framework really allows for such expansive freedom. You can completely forget how something looks or was in the realms which we know it and present something completely different and ask one “What do you think?” That framework is extremely critical especially in my practice that combines theory and visual mediums and presents new arguments or dialogues.

Zelony-Mindell: This also obliterates forms of expectations that we as individuals wish to place on a future that doesn’t exist yet. And assigning expectations to things and circumstances are a huge part of issues we see today. These systems of control and institution and heteropatriarchy are built into projecting rather than listening to one another and having a dialogue.

The pictures in Tanpa Izin are beautiful for many reasons, but one of the things that draws me to them most is their fleeting feeling. They feel intimate and hidden, or like a breath passing by, building together to create a larger picture. During your time in Indonesia how were you able to recognize personality and learn from it/imbue it into the images?

Dixon: One of the most beautiful sections from the foreword by Britt Belo that I believe defines how I think about the work is:

“ It’s highly likely that when you ask a crowd of people what superpower they’d prefer, a vast majority would say “to be invisible.” Either to be invisible or to fly, there’s something in our nature that instinctively draws us toward these two metaphorical cornerstones of what it means to be free. To be invisible and to fly means to soar through the world at whatever pace, whenever, wherever … with no one’s unsought “guidance” or permission but your own.”

I think this really defines how this aspect came about because the thing that connects Belo and myself is that we are both black women who travel pretty extensively. When you’re black and a woman one thing you never get to be is invisible, so I was working to gain this quality/personality not only for the images and how I was affecting the environment but also for myself. I wanted to see what the world looked like for once without the curiosity, preconceived notions, and stares that I normally experience when I do visit new places and locations. I also wanted to, as a Westerner, not be a loud and disruptive voice there. I wanted to be respectful and observe quietly without interjecting myself in narratives as a prominent voice.

Zelony-Mindell: It’s thoughtful to hear how you reflect on this experience and how you brought your own lived experience to making these pictures and exploring this country and land. On a separate, but related note, I’m so excited that the book just arrived yesterday! It’s so beautiful Ohemaa! I’ve looked at it a few times now and there are so many things that strike me. Reflecting on this response you gave I’m curious how this approach you describe when you were making the pictures played into designing the book?

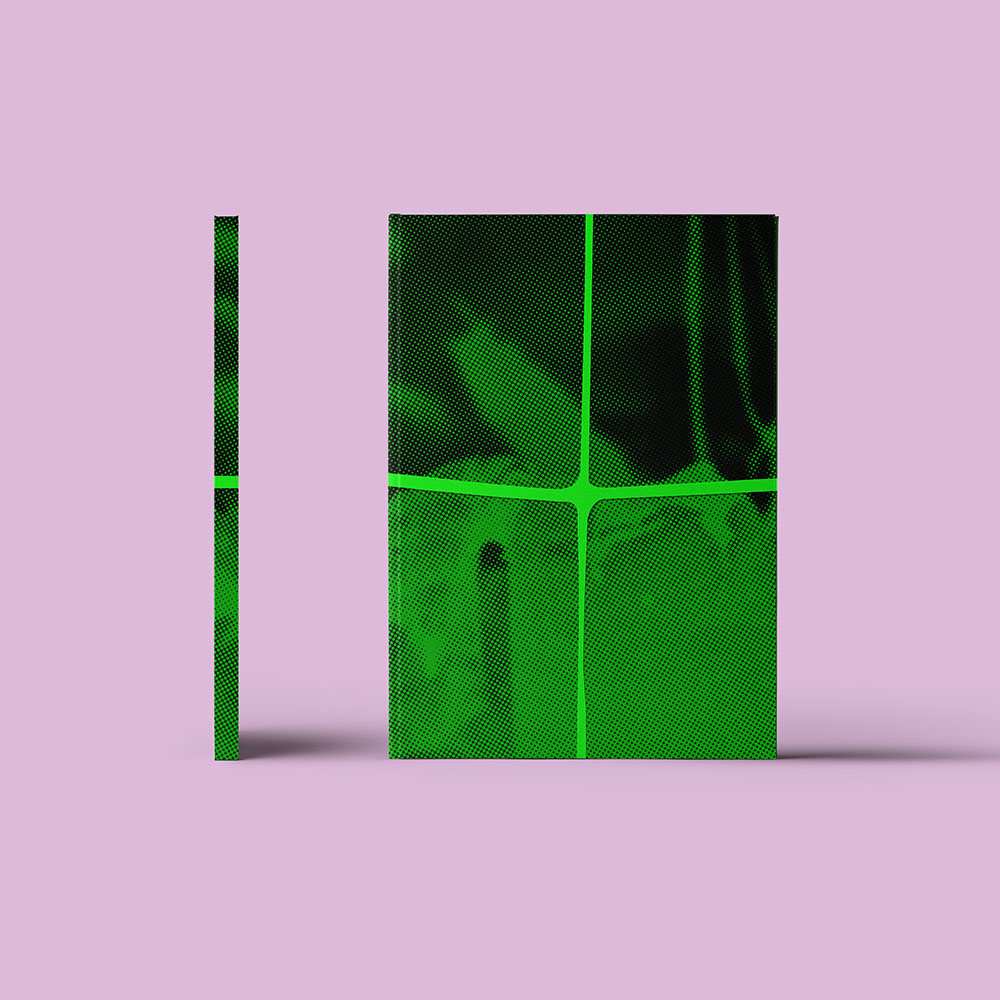

There are a lot of elements I wasn’t expecting, right off the bat, the green band that is around the book! I thought that bright greenband was just a design element printed onto the cover, it totally flew over my head that this is actually a physical object binding the publication together and needs to be taken off in order to open and look through the book. Also the different elements of full bleeds and vertical pictures printed horizontally in places where you have to turn the book. There’s a lot of visual exploring happening when actually interacting with the book that feels like an echo of how you approached Indonesia with your camera. Talk about these relationships if you don’t mind.

Dixon: So I’ve actually been practicing mindfulness and meditation for quite some time now. And no, I don’t say that to lead into a cheesy gimmick about how I found these things in Bali in some sort of Eat, Pray, Love-esque thought. I’ve been practicing it for a while to deal with my anxiety and as a way to develop my work and writing. I say this because I like to think of the book as a meditation.

There are a number of things about the book physically that are done very intentionally. The first being the band, as a way to jolt and physically symbolize to you that this will be a new train of thought as you are going through it. I wanted readers to fully and mindfully enter the book with me and be guided throughout while having space to breathe and think. The book itself is rather quiet, there’s no gigantic title printed on the front, the cover is an image obscured and you won’t find my name until the back of the book. I actually had the thought at first to completely remove my name from the physical book.

Like any meditation it begins with some direction which in this book is provided in the foreword by Belo. From that point the images are displayed in a multitude of ways, placements, directions and various annotations throughout that ask you as a reader to check in. I’m actually glad how well that’s been translating with people as they get the book physically in their hands. I’ve been getting really interesting emails, texts, and blurbs from people as they finish the book that let me know that the point is beginning to get across. I would recommend going through the book multiple times, there’s a lot more that’s been done that I won’t mention that’s left to discover as well.

Zelony-Mindell: Ohemaa this has been such an absolute pleasure chatting, exploring, and sharing! I can’t thank you enough for taking this time and sharing yourself and the pictures. I have one last question for you. Through the lens of the contemporary world we’re all living in I’m curious why these pictures are important? Both to you personally and in a larger context.

Dixon: It’s been such a pleasure as well. My entire practice is based on empathy and believing that if we all can not only view art but also deeply connect with each other through it beyond the surface we can engage in true dialogue. Underneath all of my work this core concept holds my projects together. This project asks readers to slow down and begin to have conversations within themselves. We are in a period of limbo mentally, socially, and ethically and we can begin to use tools such as art critically within this moment to catalyze conversation and change. I believe and remain optimistic that a time is coming where we all will reckon with what we do and have done and ask ourselves truly “What can we do to move forward?”. I think with this pandemic and quarantine and all the alone time we are facing we are extremely susceptible to knowledge and new ideas. My hope is that Tanpa Izin and other projects like my work in “3436” can begin to be catalysts for this dialogue in a meaningful manner.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph YOU Took in 2025, Part 4January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 5January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025, Part 6January 1st, 2026