Portuguese Week: António Júlio Duarte

© António Júlio Duarte, “Eight Photographs”

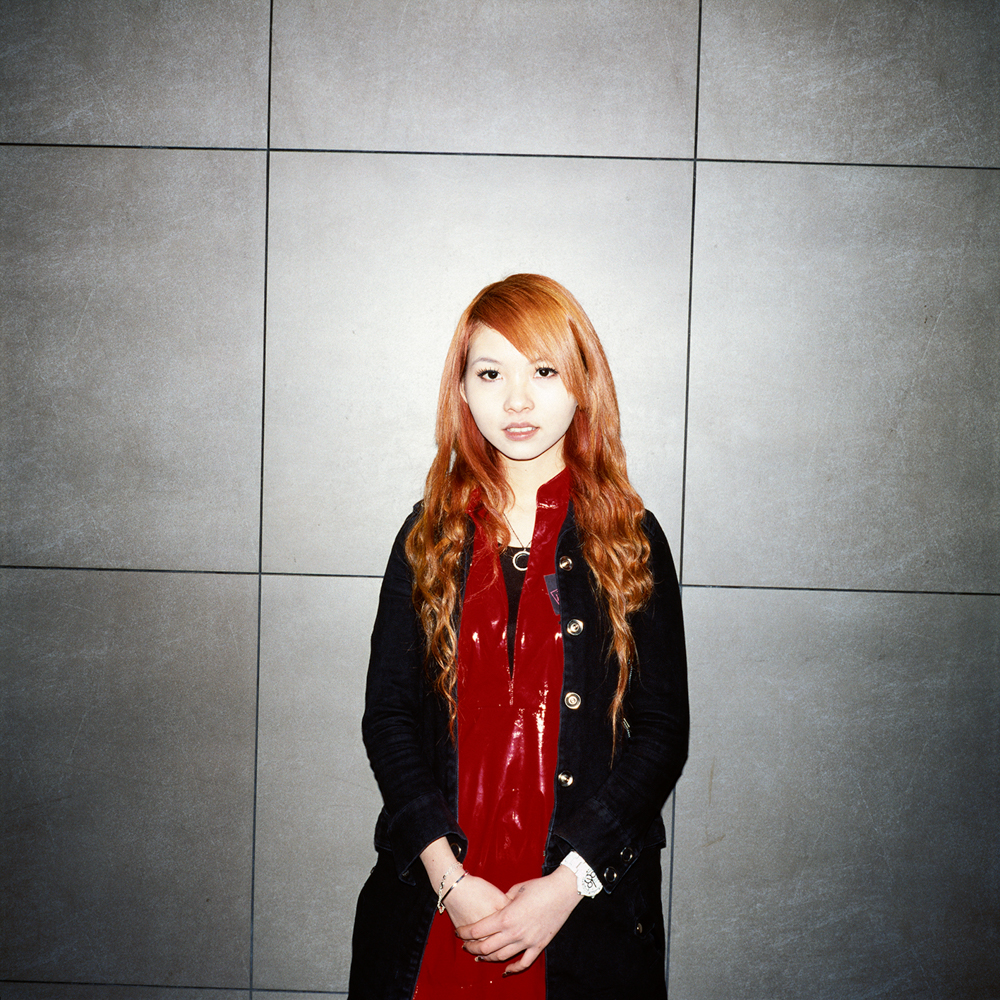

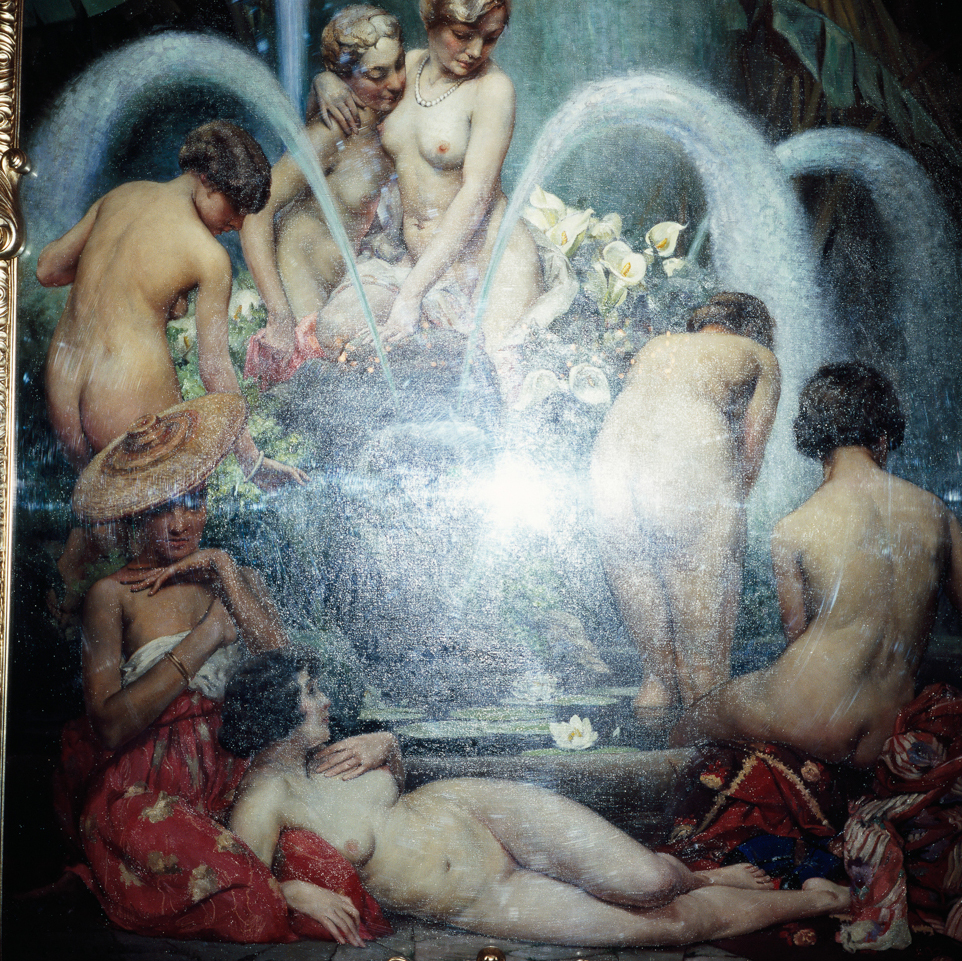

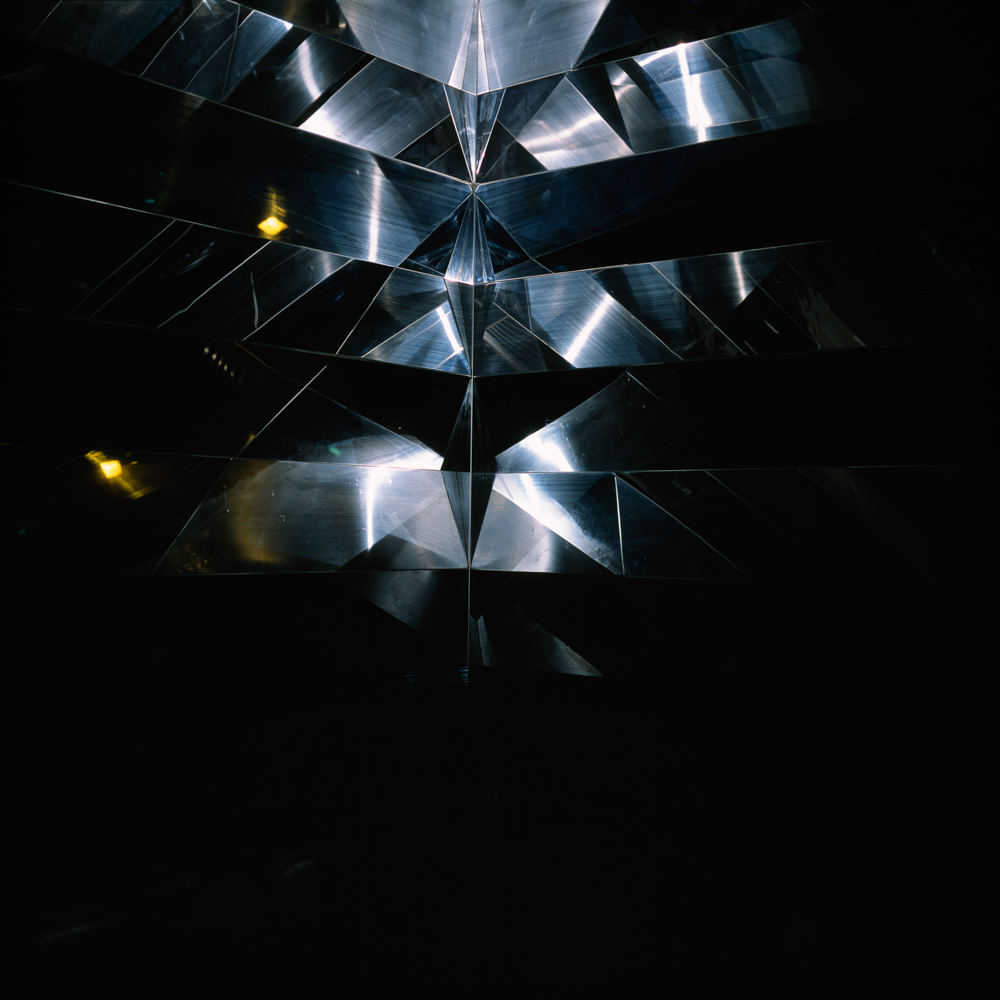

Today we will move from the rural landscapes and plants, animals and mountains, to a predominantly urban environment. Buildings of all kinds, casinos, streets, more or less successful artificial reproductions of nature (here and there with hints of desperate “true” nature), intense city life in all its layers, complexities and contradictions.

António Júlio Duarte is one of Portugal’s most recognized photographers. The great consistency in his work is a result of constant reflection on the photographic medium and the power of wandering. As far I can remember visiting photography exhibitions in Portugal he is one of the most recurrent presences. Maybe this happens because I am really fond of his street photography that is uncommon, raw, disconcerting and up to a point, strangely recognizable. And for me those are some of the strongest elements in photography in general, to produce, or make, images that look vaguely familiar, but plant the seeds for every other kind of interpretation and meanings without offering too many elements. That delicate balance is not for everyone, but he excels in doing it.

© António Júlio Duarte, “Eight Photographs”

© António Júlio Duarte, “White Noise”

© António Júlio Duarte, “White Noise”

© António Júlio Duarte, “White Noise”

Nevertheless, these images draw us to them, almost as if they ask us to stay a while longer and find out their true meaning or purpose. Definitely a trap in which I am willing to fall into. They have magnetic qualities that want us to imagine, or anticipate, that in some recent moment civilization was on the brink of collapse. Or effectively is. António Júlio Duarte is, therefore, guiding us through a permanent questioning of symbols and responses to the world that, far from offering concrete answers, push us to places of discomfort.

© António Júlio Duarte, “White Noise”

Carlos Barradas: Dear António, glad you accepted our invitation to be part of this Portuguese photography week. How would you describe your photographic practice?

António Júlio Duarte: I never know what to answer when people ask me what kind of photographs I make. They come as an intuitive, sometimes visceral, response to places, people, animals and situations.

© António Júlio Duarte, “Mercury”

© António Júlio Duarte, “Mercury”

© António Júlio Duarte, “Mercury”

CB: Your work is quite related to the urban environment. In a Portuguese TV documentary, Entre Imagens, you said that what you photograph in the East you could photograph anywhere else. I am quite drawn to that, in the sense that I think that sometimes (if not always) photographs become much more interesting when they’re not immediately explainable or identifiable. Could you elaborate on that?

AJD: It’s quite paradoxical. The photographs I made in the East could only be made there because it’s where the subjects are, but it really isn’t important to me that the place would be recognizable. My work is more about my relation with a place than about the place itself.

CB: White Noise. Japan Drug. Suspension of Disbelief. I love the titles in your work. How do they come up? Do you find something that binds the whole work together or you start from it and develop the work from then on?

AJD: Titles are as difficult to come up with as children and pets’ names. They usually come at an early stage of editing the work as something the work is asking to be called- a word, a phrase or a concept. From that stage on, the title starts to influence the final editing.

© António Júlio Duarte, “Eclipse”

© António Júlio Duarte, “Eclipse”

CB: Throughout your career, you have used medium format cameras, disposable cameras, photocopies, but also thought about and spoke of shapes: square, rectangle, circle. What was that search based on? You say often that you want the viewer to recognize what you’re showing as a photograph, and not as “reality”. And you also say that you don’t want to go unnoticed. All the contrary, you want people to be aware of your presence. I find that really interesting.

AJD: I’m interested in the basic aspects of photography. That can be reduced to light and framing. Also the physical existence of the photograph as object, be it a print, a printed page, or a screen. The awareness of my presence came from a technical decision of using a flash to photograph instead of a tripod.

CB: In my opinion, a lot of what can be called street photography tries to be “funny” or seeking the absurd in everyday life. But in your work, it’s the weirdness, the improbable, the raw, the science fiction produced by reality, the thing that happens, or exists, against all odds. Would you agree with that?

AJD: Yes.

© António Júlio Duarte, “Against The Day”

© António Júlio Duarte, “Against The Day”

CB: In anthropology, Claude Levi-Strauss put forward the idea of structuralism- that, in spite of cultural differences, humans would have a common underlying structure. Scientifically, this idea was abandoned later on, but I am interested to have your opinion on the visual part of things. I mean, apparently people are reacting more and more to the same visual stimuli; would you say that we are going towards a visual structuralism, in a way? To put it in other words, are we becoming more and more visually homogeneous? Is there a universal side, or understanding, to things and people photographed?

AJD: I think we are becoming more and more visually homogenous due to the fact that internet brought the possibility of images to become truly global and start to replace language as a form of communication. We all use emojis, right?

CB: I am particularly interested in the visual traditions, or visual culture(s). You said that in the US it’s quite difficult to photograph something that hasn’t been photographed before. Do you think that happens because of the massive amount of images we get from the US, either good, as with the work of people such as Winogrand or Friedlander, or bad, with Instagram and all other social media?

AJD: Being the dominant culture since WWII, it’s almost impossible not to be influenced by their images, especially the bad ones.

© António Júlio Duarte, “Japan Drug”

© António Júlio Duarte, “Japan Drug”

CB: Is there such a thing as a Portuguese photography? In either cases, why?

AJD: I like to think photographs are above geographical specificities.

CB: Last but not least, the future, both personal and for Portugal’s and the Portuguese artistic scene?

AJD: I can’t predict the future and that’s great.

CB: I bet you would love to photograph the end of the world?

AJD: What would be the point of doing it?

© António Júlio Duarte, “Japan Drug”

António Júlio Duarte (Lisbon, 1965) lives and works in Lisbon. His work has been exhibited regularly, in Portugal and abroad, since 1990. A selection of recent solo shows includes Eclipse at Galeria Bruno Múrias, Lisbon, 2020; White Noise at Quartel da Arte Contemporânea de Abrantes, Coleção Figueiredo Ribeiro, Abrantes, 2017; América at Galeria Pedro Alfacinha, Lisbon, 2017; Suspension of Disbelief, CAV, Coimbra, 2016; Mercúrio at Galeria Zé dos Bois, Lisbon, in 2015; and Japão 1997 at Centro Cultural Vila Flor, Guimarães, in 2013. He is the author of multiple books, among others: White Noise (2011), Deviation of the Sun (2013), Japan Drug (2014) and Against the Day (2019) published by Pierre von Kleist Editions. He is represented by Galeria Bruno Múrias in Lisbon.

Follow him on Instagram: @antoniojulioduarte9

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Yi Wan Gyo: Nirvana-Beyond DarkJanuary 13th, 2026