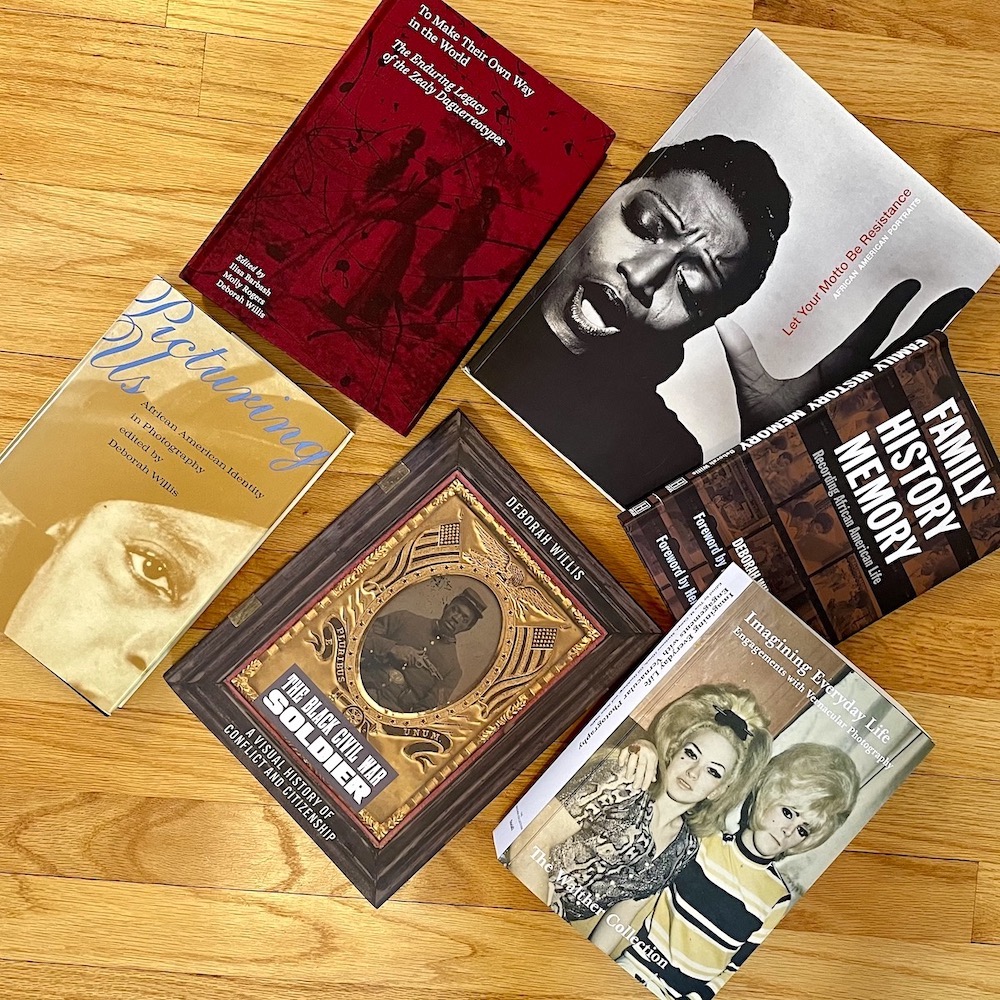

The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship: Dr. Deborah Willis in conversation

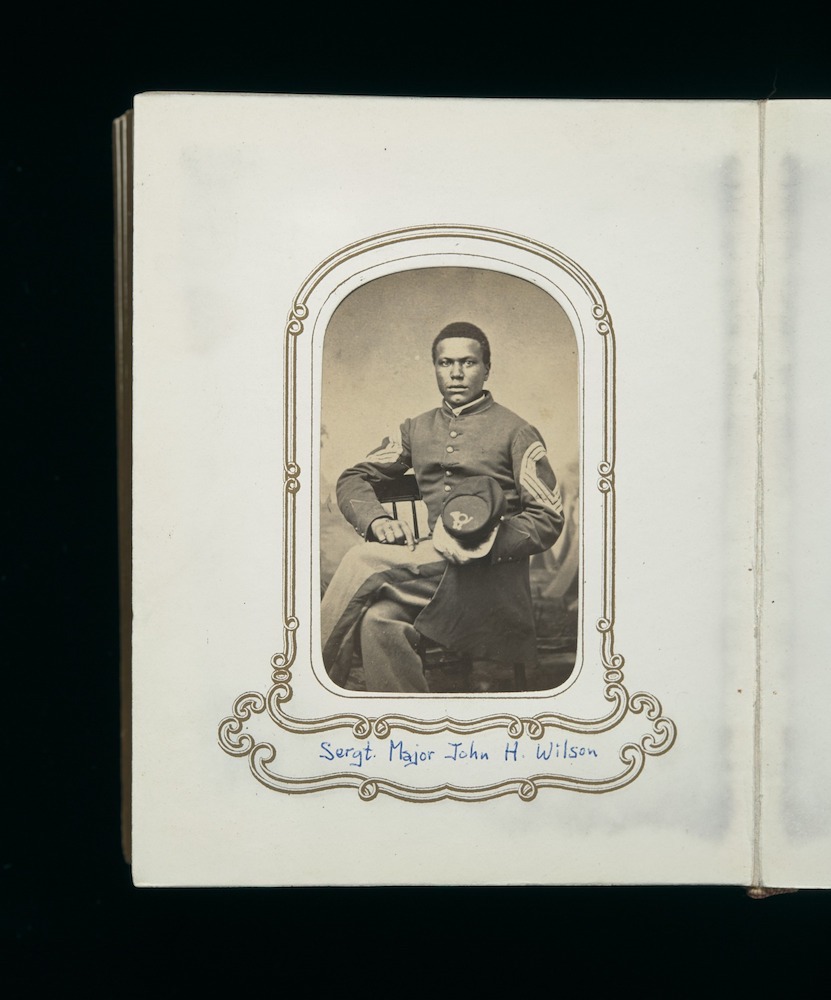

I’m going to keep this introduction quite short, as the conversation below covers so much ground. I’ve known Dr. Deborah Willis since 2000, when she was a visiting professor at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. Spending time with Deb Willis is one of my favorite things to do, so I was delighted when Aline Smithson asked if I’d like to talk with Deb about her newest book, The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship, for Lenscratch. That this conversation took place in January, the day after the inauguration and just a couple of weeks after the attack on the Capitol, made the things we discussed, particularly Deb’s groundbreaking and influential work, and how she came to make it, that much more resonant.

I’m going to keep this introduction quite short, as the conversation below covers so much ground. I’ve known Dr. Deborah Willis since 2000, when she was a visiting professor at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. Spending time with Deb Willis is one of my favorite things to do, so I was delighted when Aline Smithson asked if I’d like to talk with Deb about her newest book, The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship, for Lenscratch. That this conversation took place in January, the day after the inauguration and just a couple of weeks after the attack on the Capitol, made the things we discussed, particularly Deb’s groundbreaking and influential work, and how she came to make it, that much more resonant.

How you doing?

Well, after yesterday, I’ve felt so relieved to be able to breathe, to be inspired. Amanda [Gorman], oh my goodness.

It was beautiful. I took the day off, I wanted to be all in. She was amazing.

Really, really amazing. It’s such a relief. We got to see Michelle again. And my girl Hillary Clinton, her hair was flowing; Michelle’s hair was blowing. I mean, everybody’s hair was looking good.

I loved Hillary’s boots. She was saying, you know, I’m staying warm, I’m staying comfortable. Because . . . the stilettos.

Oh, I couldn’t believe that—I guess the designers made the choices, and after the big fuss over Tyler’s cover [with Kamala Harris for Vogue]. . . .

[Laughs] Well, you know, what else I have been doing this week? I’ve been reading Deb Willis. I hadn’t read Picturing Us in a long time, and I re-read Family, History, Memory, and your essays for Imagining Everyday Life and To Make Their Own Way in the World. You’re inspiring. I’m excited to talk about your new book.

Tintype of a Civil War soldier. His buttons and belt buckle are hand-colored in gold paint. The hand-coloring on the buckle reads backward “SU,” which when considered that the image is reversed, reads “US,” the traditional inscription on Union Civil War belt buckles. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from the Liljenquist Family Collection, 2011.51.12

Portrait of unidentified young African American soldier in Union uniform with forage cap, ca. 1860s. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-37079)

Yes, you read drafts [laughs].

I did. So this is a really personal conversation, because of our relationship and because of my experience of being in your head as an editor—your work feels, I don’t know, metabolized in me. I’m always realizing anew how editing or reading things that you work on, that you’re researching, has changed how I look at and perceive things.

And I’ve been thinking about what you wrote in Picturing Us about reading Sweet Flypaper of Life when you were seven. I checked it out of the library when I was older than you, at 14 or 15, but it made such an impact—one of the big books of my life. I reread it yesterday and was trying to think, how did it change me to read this book? Just for one, I know that how words and images work together have stayed an obsession of mine since that time. But everyone is so gorgeous and alive in that book; it is sticky with the sweet flypaper.

We had a little area right outside our back door, and flypaper used to hang right there. You’d go in and out, the screen door going in and out, and that flypaper . . . and I’d always think, why did it have that title, Sweet Flypaper? You know, you’re drawn right to it [laughs].

That’s the central aspect of how the arts engage us, not only in terms of literary arts but also the visual, including dress and fashion. The power of the word and the visual is so inspiring for us; it really does shift how we think.

And then to see the New Yorker article and that video the journalist made [about January 6th]. These people grabbing up papers; they didn’t even know what they were looking for: Oh, we need to take a picture of this or that. It showed the lack of respect that they have, and it saddened me as evidence—to photograph without any understanding.

I’m glad the journalist was inside with them and that he released the video, because it placed us in this imagined space that the officials were in. I mean, just seeing how dangerous it was for them. That was a wake-up call . . .

Right? Talk about reaping what you’ve sowed. Mike Pence . . . they came for him. I hope repair is possible, that there will be a new collective consciousness about America, who we are . . . and who we aren’t.

Yes . . . it’s time to try and repair.

[Deb holds up copy of The Colors of Photography, edited by Bettina Gockel]

Oh, wow, what’s that?

This just arrived today. My essay has a picture of my niece in it—from my first color theory class, in ’72. I was told that I didn’t have the right model. She was wearing red, she had all the colors going; we had the color chart. And the first response I had, from one of my white male cohorts, shocked me into silence. He said that I should have used a “Shirley” card, which I had never heard of, so of course I asked, Well, who is Shirley and what? What’s the problem with her card? Oh, a black girl was the model. Later I did attempt to use the Shirley card, and it didn’t have any of the right colors.

So in this essay, I’m looking again at this whole thing. You know, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, they used that Polaroid ID-2 and referenced Kodak’s Shirley cards. And I talk about hand-tinting photographs, and then looking at how in the twentieth century, Yale opened up their color collection with Van Vechten. The Library of Congress did the same with their FSA photographs.

So I used some of those images and then ended with Sheila Pree Bright and Omar Diop.

I was just about to say that I learned about Shirley cards from you, because of editing an essay you wrote a while back where you talked about that experience.

This is that essay!

No wonder [laughs].

Just to think about the power of that moment. . . . Okay, this all leads to images of the black civil war soldier. . . .

Yes, it does. I’ve been thinking about how working in archives is a kind of time travel, with not only the power to change the future but to change the past.

That’s how I’m going to introduce myself from now on: Alexa is my friend, and she says that I’m a time traveler.

You should! You’re responsible for so much of this work, pulling from archives to reinvent the Archive, or rather create a new family history. And I mean family in the broadest, most collective sense. You ended your recent conversation with Isaac Julien by talking about the need for better educations, and I do think that’s the transformative thing.

You know, I was lucky in elementary school; I had three black teachers and I remember there was Mr. Toss and Ms. Foster and another one who ended up marrying my uncle [laughs]. We had Black History Week then, and Marian Anderson was from Philadelphia: We were bombarded with Marian Anderson’s story. The experience of growing up in Philadelphia, but also of having black teachers, really kept me focused, and curious. I had no idea that I would end up spending my life working in archives, or as you say, being a time traveler [laughs].

There were so many stories that I never heard in elementary school, middle school, high school—nothing. Langston Hughes was always in my life because my father had his books, and Richard Wright’s books. So we had the books, but the public schools didn’t. I just imagine what it would have been like if we had had the materials, the texts, early on.

I remember a white counselor telling me that I could only be a “bedpan nurse,” you know? So don’t even think about going to college [laughs].

I never heard that story.

My future is what? . . . You know, me! I didn’t even know how to change a diaper.

[both laugh]

I wasn’t even a babysitter when I was growing up. I’ll never forget her. I looked at her; I was like, me? I had no idea that that was said to a number of people I’ve met over years. They told me their guidance counselor said the exact same thing, and that they would refuse to write letters for them to go to college.

So that stayed with me, and of course, I kind of laugh now when I think about when I went home, appalled and angry, and told my parents about it. And then I talked to a cousin who went to another school. I didn’t know that my sister, who graduated before I did, had been told the same thing, and she went to Howard.

It was so many black kids’ experience. There was a guy who sat behind me in school, his name was Sylvester White; we were always together in the “W’s.” I’ll never forget him. He said to me, “I bet when you finish school, you’ll join the Peace Corps or something like that.” [laughs] He said, “You have to do something like that, because you’re different. You’re going make a difference.”

I was like, wow, because people were gone, people died—they went to Vietnam. It was really sad to think about those young people in the army; so many boys died whom I went to junior high and high school with.

Having those experiences in the past and talking to you now . . . I have not thought about that counselor much since then, but I remember the impact that she had on me. I had decided that I wanted to go to the Philadelphia College of Art, now University of the Arts, but my father wanted me to have “practical experience” and sent me to a junior college, now Peirce College, which was across the street.

My father wanted me to work at city hall. He was a policeman and he had a grocery store at the time, and he’d had a tailor shop prior to that, so he was about work. He was a worker.

I decided I wanted to work at Temple because then I could prepare to take the SAT and take classes. I worked for a woman by the name of Linda Clark at the Center for Community Studies. And she was just a powerhouse. She wore those high heels, like Nancy Pelosi wears, with these wide dresses and belts, but she trained Vista volunteers, and I was her secretary.

Sylvester White was getting closer and closer.

He was. I was her secretary. We used to travel to West Virginia to train people in the holler. The faculty members were activists. I had a teacher—his name was Lawrence Reddick. He taught the history of religion and history, meaning he also taught African American history in that course. I had no idea until some years later that he had been the director of the Schomburg Center, in 1948.

That’s crazy.

He was the brightest person I knew. That’s when I started learning new information about the Civil War. When we were kids, we visited Civil War sites and monuments, Gettysburg, all the stuff, because it’s part of the Pennsylvania historical experience.

I continued to take photographs, and because I stayed involved with photography and taking pictures, I decided to organize a portfolio to apply for school at PCA. I moved to New York for a year to study at the Germain School of Photography—I took scientific photography and portraits and landscapes.

I took all of these photography classes, and while I was taking classes, I also taught photography at the Fashion Institute with neighborhood Youth Corps, so stories were always part of it, teaching young people about photography.

I applied to Moore College of Art, which was all women, and at PCA. I got into both and was really excited. PCA gave me more money and that really helped [laughs].

That’s when it all began. I was noticing the missing gaps in the histories and wondered why we weren’t studying black photographers. I knew a lot about black photographers in terms of photojournalism from when I was la wee child, because I grew up in my mother’s beauty shop reading magazines. Ebony and Jet had black photographers; Life magazine had black photographers, including Gordon Parks.

And I have spent a lifetime working through that, including the work on this book about black Civil War soldiers. Having that early experience of not being a traditional historian or researcher but working as an artist . . . I didn’t have rules. I had that sense of the unknown, of how do you do research? I have always wanted to do new research, find new materials, and search for and tell different stories.

I had Reflections in Black and Posing Beauty behind me. And while working on Envisioning Emancipation with Barbara Krauthamer, I often found photographs of black soldiers.

It got bigger. I met collectors, some of whom eventually gave or sold their collections to the Library of Congress or to the Beinecke Library at Yale or to the Wadsworth Athenaeum. After spending time with these black soldiers, I wanted to hold onto their images, but I couldn’t afford the millions that they were asking [laughs]. I was excited to know that these photographs existed and decided, okay, we need to create this story. With Envisioning Emancipation, we had some images, and then I started reading letters. . . . We were taught that black people couldn’t read or write then, and here I am reading letters that told people’s stories in their own words. Some soldiers, of course, did have scribes who wrote letters for them, but many soldiers had journals and diaries that they kept. People died with letters to their wives in their pockets and with a photograph in their hands.

I wanted to reimagine the larger story.

There’s one story about a woman that just breaks my heart, touches my heart, that stays with me. When black soldiers entered Richmond, there was such a sense of pride, and one black soldier, he’s marching through—women and men and children were standing in the streets—and a woman stops one of the soldiers and starts asking him all these questions. She had been looking for her son for years. But to hear her story, to read it . . .

This is one of my favorite stories in the book—let me read their exchange as the soldier wrote it in a letter.

I was questioned as follows:

“What is your name, sir?”

“My name is Garland White.”

“What was your mother’s name?”

“Nancy.”

“Where were you born?”

“In Hanover County, in this State.”

“Where was you sold from?”

“From this city.”

“What was the name of the man who bought you?”

“Robert Toombs.”

“Where did he live?”

“In the State of Georgia.”

“Where did you leave him?”

“At Washington.”

“Where did you got then?”

“To Canada.”

“Where do you live now?”

“In Ohio.”

“This your mother, Garland, whom you are now talking to, who has spent twenty years of grief about her son.”

“I cannot express the joy I felt at this happy meeting . . . “

I’m reading it along with you . . .

I mean to express that, to feel that, and to know that she had searched all these years. . . . I wanted to try to look for a way to tell women’s stories, mother’s stories. In the book, there are mothers who wrote letters to Abraham Lincoln, telling him to “make sure you take care of my son; I’m giving you my son, make sure he gets paid.”

The photographs to me were central, because they were personal, the way that soldiers posed in their uniforms, their style of dress—the way that they felt when they put on their uniform. That aspect of how identity was transformed, knowing that they had hope. I think that is central in how we describe this experience, of these soldiers who were looking for ways to shape their future by joining up—to think about their own experiences of “injustice,” how they were able to fight that battle.

And then there were some horrific stories that were shared, where a white slave owner saw, as he saw it, his “human property” in a Union uniform. He wrote to the head of the army saying, he’s my property and needs to be back on my land; he needs to be repatriated back to me. So there are those struggles in these stories and then different ways of thinking about, how do you look at these images?

That’s another reason why it’s so important to have letters and diary entries in the book. I mean, there are hundreds of books on the Civil War, but every time I’d find a book that had letters in it, there’d maybe be one letter with a black story that focused on black soldiers’ commitment to fight for their freedom.

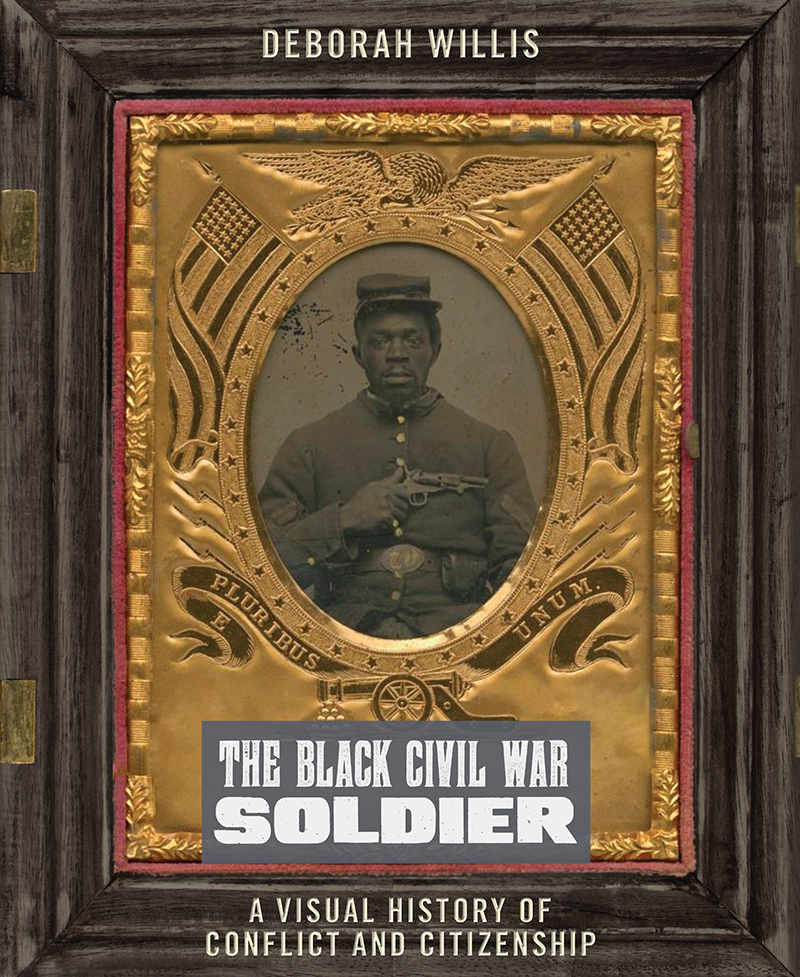

Fleetwood’s diary entry, June 15–22, 1864. Christian A. Fleetwood Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, 147.00.00

Tenth Army Corps, a Union army regiment composed of escaped slaves, in formation, near Beaufort, South Carolina, 1863 and 1864. Photographer, Samuel A. Cooley; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division; LC-DIG-stereo-1s04441LOT 14110-5, no. 51 (H)

Portrait of Harriet Tubman, 1868–69. Photographer, Benjamin Powelson; Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2017_30_47_001

William P. Powell Jr. was one of the first African American physicians to receive a contract as a surgeon with the Union army. Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG 15, National Archives

One story that struck me, that I keep thinking about, is the woman who writes to the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Pensions, for her husband’s pension after her applications have been repeatedly denied. As a way to identify him, she sends the one photograph of him she has, and she writes, “Please send it back.” And you found it still there in one those files. . . . To think about all of things that one photograph meant and represented, and what it meant to send it, and lose it. For it to stay housed in the filing cabinets of bureaucracy.

That’s it. Susan and Henry Brewster. We even traveled to upstate New York to the town where she lived; we had the address and found the street.

That photo, it’s still in the pension record. When we look at research and the position of photographs, it’s important to remember the value of pension records. I was reading a biography by Jill Watts—Hattie McDaniel: Black Ambition, White Hollywood—and I did not know that her father was a Civil War soldier, and that he, they, fought for years to try to get his pension. There is a photograph of him holding his rifle.

He was injured, horrifically, and the pain and suffering that he experienced lasted for years. I mean, Jill describes it in the biography, how important it was to [Hattie McDaniel] for them to recognize his plight, and why she wanted that role in Gone with the Wind.

I looked at all of the screen tests for the film. I think about the complexity of the role that she had to play, and the way that she was also able to make sure that she had money to help other actors when they arrived in Hollywood. So I mean, I’m just so honored to have the opportunity to collect these images, but also to rethink them, to recirculate them, in a different way.

I had two different thoughts at the same time. One is when you see these images, you immediately realize that you haven’t seen them before—you recognize absence in the same moment that you regard presence.

I was reading your interview with Carrie Mae Weems in To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes, where she speaks about how she’s approached bending power toward social justice—she says she tries to create equity in her art by “exploring the complexity of who we are within the larger frame of the culture.” So much of your work is about joy, beauty, nuance—you’ve been able to do this, to show it.

Another thing I was thinking about is storytelling, creating stories. I guess this is where the Center for Documentary Studies comes in. Sometimes I get tired of the word storytelling because it elides the act of listening. Without a listener, there is no story. And this is about sharing stories that reveal things about larger structures (and silences). . . .

Right. I treasure that year I was at the Center for Documentary Studies [as a visiting professor] in part because of that project, what was it, Behind the Veil?

Yes.

Behind the Veil was an important initiative, to be able to hear, to read, people’s experiences of Jim Crow. That year, I was experiencing a personal loss, and I really loved the time I spent working with young people in the high school: their project was on beauty, finding beauty in their home, having them photograph what they described as beautiful. And that’s what I experienced in this research, not only the tremendous loss that we all experienced, and as we feel it today—but the holding onto family, the love of family, found in these photographs.

Portrait of an unidentified African American soldier. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; LC-DIG-ppmsca-37532 LC-DIG-ppmsca-27532

Unidentified African American soldier in Union corporal’s uniform. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-34366

I was thinking when I read your book about how immediate the Civil War seemed to me growing up. When my mother was a girl they would have parades in downtown Jacksonville, Florida, that included Confederate veterans. Veterans in this case were synonymous with very old, white, long-bearded men.

These images, letters, documents are part of a collective American family that’s fuller, richer, and truer than the history I was taught.

It’s fascinating, because the archives in the South, like the Florida Memory archive, are places where I found some unusual photographs, and you know, Virginia’s Museum of the Confederacy. So many images haven’t been digitized, but the photographs are really wonderful.

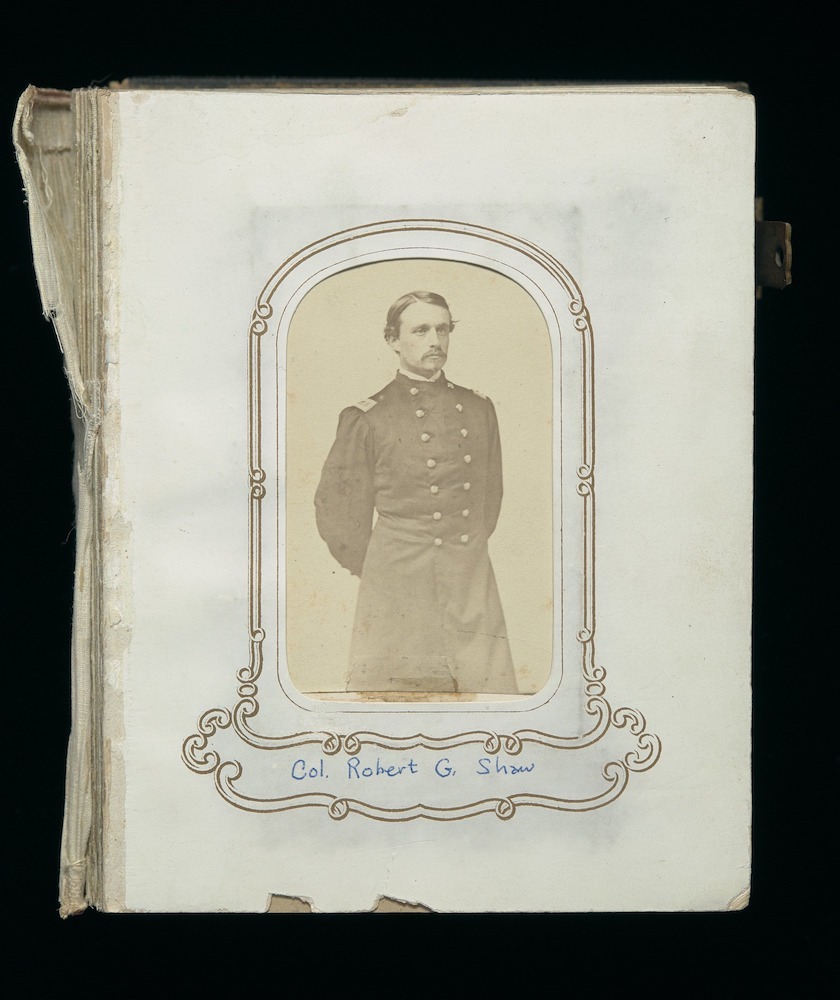

I think about Charlotte Forten entering the Sea Islands wearing pants—“a girl,” a young teacher from Philadelphia, entering into that space, meeting Colonel Shaw weeks before he died. She writes about how she first met him . . . he had just married and talked about the joy of that, but also acknowledging that people had daguerreotypes in their tents, and noticing those things. So there are those little details.

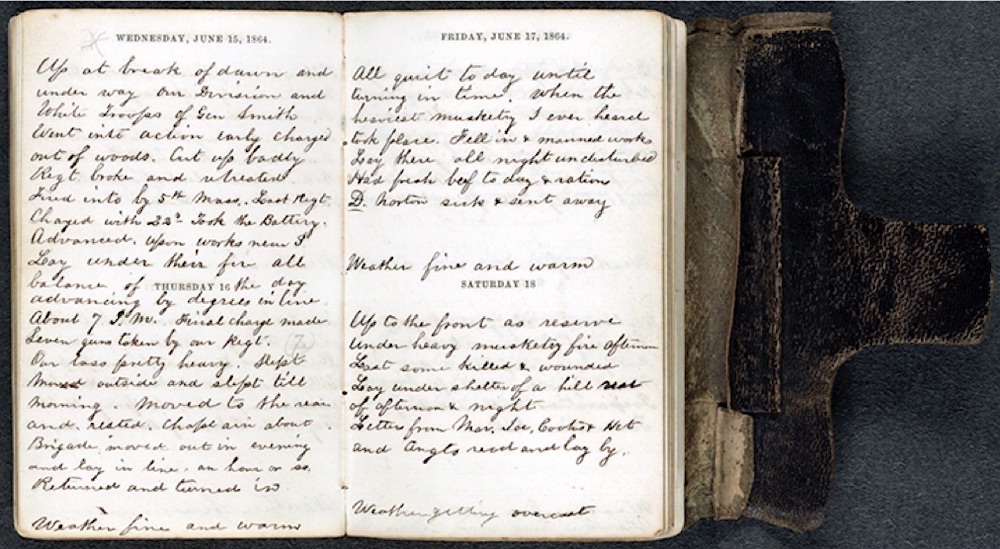

Sgt. Major John H. Wilson. Photographer, John Ritchie; Carte-de-visite album of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Garrison Family in memory of George Thompson Garrison, 2014_115_8_043

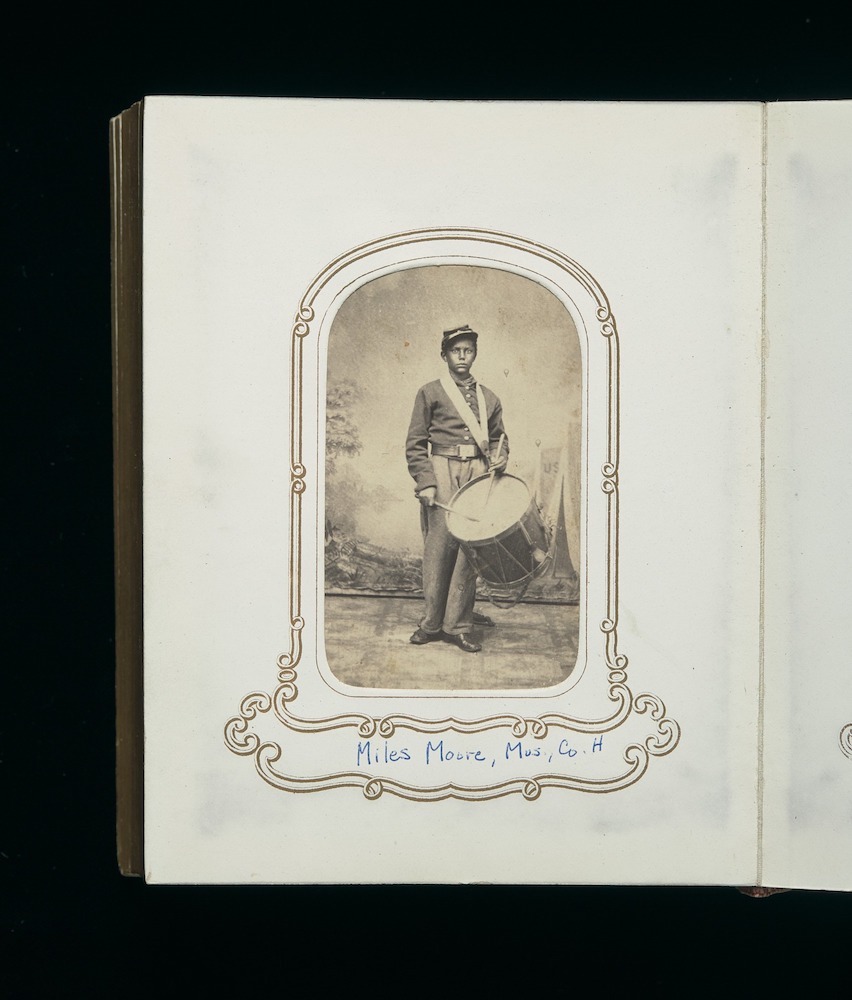

Miles Moore, Mass. Co. H. Photographer, John Ritchie; Carte-de-visite album of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Garrison Family in memory of George Thompson Garrison, 2014_115_8_027

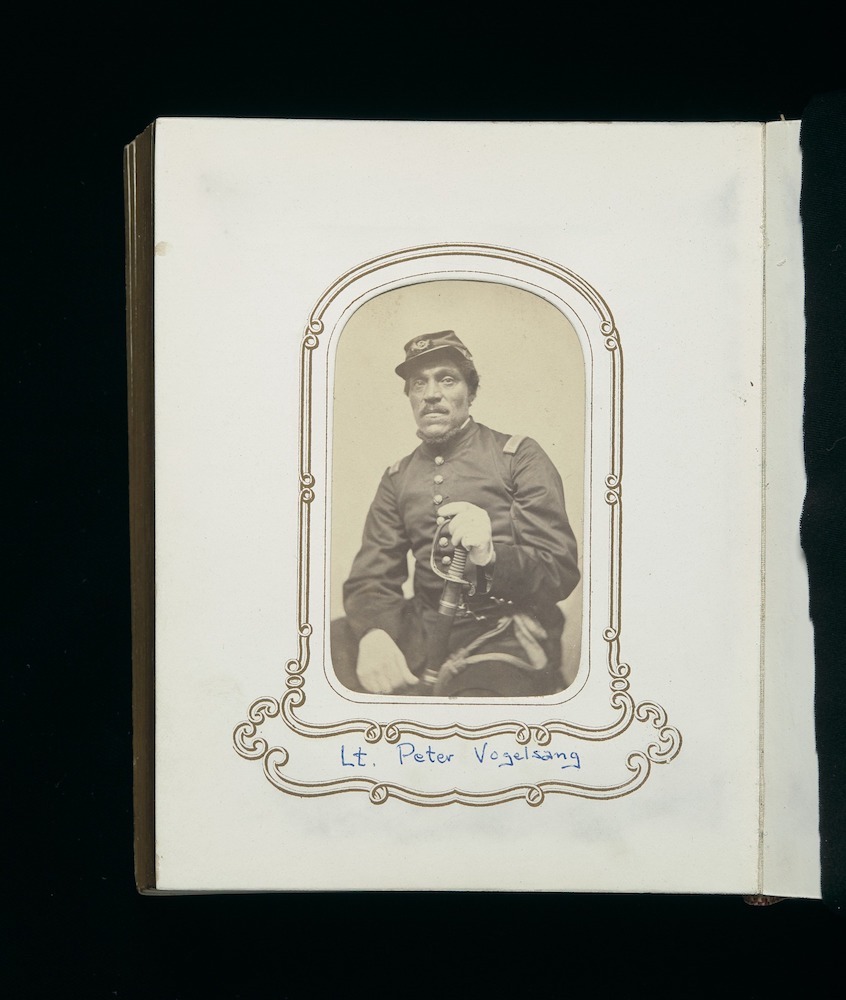

Lieutenant Peter Vogelsang. Photographer, John Ritchie, Carte-de-visite album of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Garrison Family in memory of George Thompson Garrison, 2014_115_8_021

Carte-de-visite album of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Garrison Family in memory of George Thompson Garrison. 2014_115_8_001

The concept of “collective memory” could sound almost passive when in fact it is so active, especially when we see white people carrying Confederate flags, some of them inside the Capitol on January 6th.

I was shattered on January 6th—that someone would put a noose up on the grounds of the Capitol . . . and feel free to do it so openly . . .

Just understanding the importance of the visual experience and how it connects with today’s social protest movements and photography . . . the range of people who are using their cameras to tell stories. That’s when you think about re-telling, how central storytelling is. With this imagery being digital, their dissemination is open. So again, if we can teach our students not only how to make images, but how to make them useful. . . .

We have this whole history of imagery that provides us with another way of looking at contemporary experiences, of connecting then to now.

It is also really great for me to link a lot of these images to the work that I did at the beginning—like I think I just graduated last year [laugh]—because all of these stories are overlapping and connected.

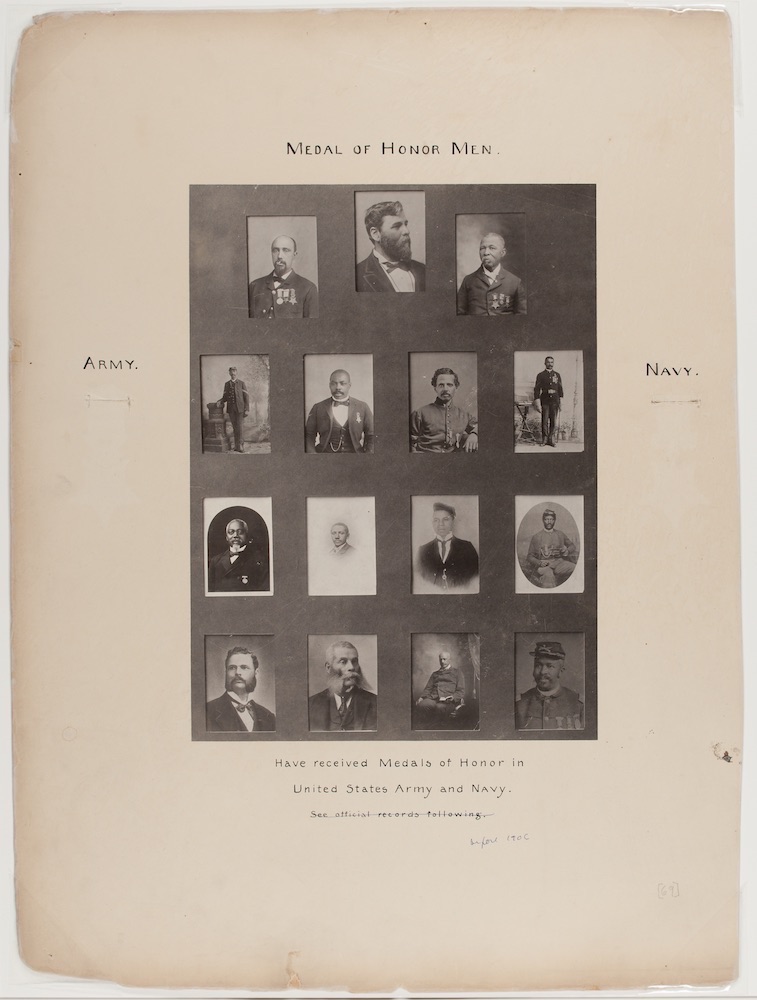

Portraits of fifteen African American soldiers and sailors who received Medals of Honor for service in the Civil War, American Indian Wars, and Spanish-American War. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, call number: LOT 11931, no. 69 [P&P]

You’ve worked this ground in such different ways; you’ve gone deep in filling out photographic history to give us a revised, repaired vision of lived history.

I love that we can listen to “slave” oral histories from the WPA and have the opportunity to visualize them through images. I mean, there were some really good photographers who documented the people, so we have a chance to use photography as a memory holder for these experiences. That was central for me in trying to understand Frederick Douglass’s words and how he used photography. And I love the way that Isaac [Julien] was able to recreate that history with such richness, with colors, you know.

And I turn back to Carrie Mae Weems’s From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried or While Sitting Upon the Ruins of Your Remains and think about the historical references that she brings to the forefront with her images, and with her own body. You know, how do we think about portraiture?

We can talk about the negative aspects of portraits that were made, but we can also reflect on the new experiences we’re able to have by looking at portraits, by looking at portraiture itself, through a new lens, not of revision but maybe of a new story. . . .

Yes to a new story.

So maybe we can end with Zenzi.

Yes! How is she?

She’s great. And in terms of just understanding images, she’s a soon-to-be two-year-old who really understands the photographic moment. She poses. When she walks into this house, she sees images of herself at different stages in her life, and she wants to see that I remember a moment that she wants to show. And so when I think about this recycling of images—Zenzi wants to follow me and show me photographs, she wants to talk about the stories.

So it’s a joy to see someone developing a visual language. She’s so young and already she’s able to look at family and the preservation of family through pictures.

The conversation with the past is really never over.

Yes, and I really love the fact that I’m able to experience that with her.

You know, I could talk to you all day.

I know, we do.

[Both laugh]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Deborah Willis is University Professor and Chair of the Department of Photography & Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University and has an affiliated appointment with the College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Social & Cultural, Africana Studies. She is also the director of the NYU Institute for African American Affairs and the Center for Black Visual Culture. Her research examines photography’s multifaceted histories, visual culture, the photographic history of Slavery and Emancipation; contemporary women photographers and beauty. She has pursued a dual professional career as an art photographer and as one of the nation’s leading historians of African American photography and curators of African American culture.

Dr. Willis is the author of Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography, which received the Infinity Award for Writing; Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present; and Posing Beauty: African American Images from the 1890s to the Present, as well as Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery with Barbara Krauthamer and Michelle Obama: The First Lady in Photographs, both of which received NAACP Image Awards. She has received MacArthur, Guggenheim, and Fletcher fellowships and has been a Richard D. Cohen Fellow in African and African American Art, Hutchins Center, Harvard University.

Dr. Willis was the Lehman Brady Visiting Joint Chair Professor at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University in 2000–01.

Alexa Dilworth is publishing director and senior editor at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, where she also directs the awards program, which includes the Dorothea Lange–Paul Taylor Prize.

In 1995 she was hired by CDS to work on the editorial staff for DoubleTake magazine. She was also hired as editor of the CDS books program at that time and has coordinated the publishing efforts for every CDS book—among them, Road Through Midnight: A Civil Rights Memorial by Jessica Ingram and Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897–1922, edited by Margaret Sartor and Alex Harris; Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II: Photographs by Bill Manbo, edited by Eric L. Mueller; Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene: Photographs by Gerard H. Gaskin; Iraq | Perspectives: Photographs by Benjamin Lowy; and Literacy and Justice Through Photography: A Classroom Guide.

Dilworth has a B.A. and an M.A., both in English, from the University of Florida, and an M.F.A. in creative writing (poetry) from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025