Beth Galton: Memory of Absence

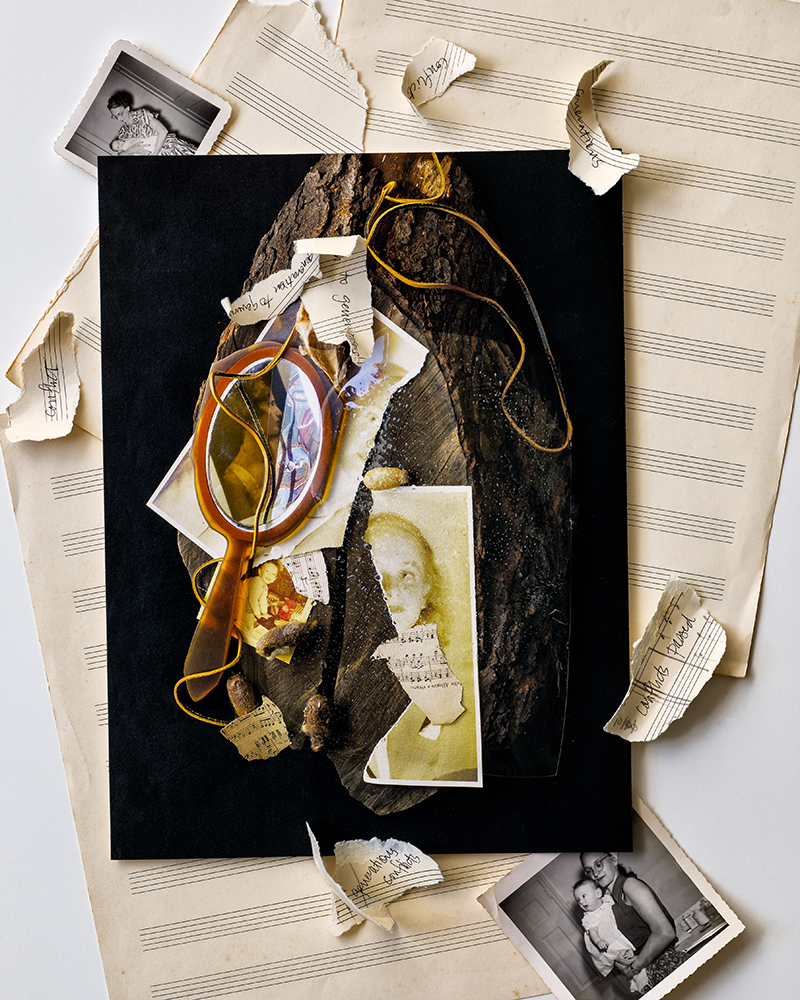

©Beth Galton, To Make Starch Stir Flour

Projects featured this week were selected from our call-for-submissions. We will be accepting new projects for review from April 4th-10th, 2021. Today, we are looking at the series Memory of Absence by Beth Galton.

Beth Galton is a photo-based artist, with an educational background in the natural sciences and 30 years of experience as a professional photographer in the editorial and commercial world. Her personal practice brings these elements of her history together, using them to explore her world through the nature of time and organic forms. Galton collects objects, items from her past and botanicals which she often manipulates and dries to constructs still lifes. In her photographs, these assemblages and portraits connect the viewer to the ecological cycles of the natural world, including their own aging and mortality. Galton often uses natural light to capture these compositions by using a large format camera and digital back.

Galton’s artwork has been exhibited in shows throughout the U.S. and Europe and she was previously represented by Marlborough Gallery in NYC. Most recently her work was seen at Montpellier Contemporian, Montpellier France, Wave Hill, The Center for Fine Art Photography in Colorado, the Center for Photographic Art in California, Beth Urdang Gallery in Boston and was part of ‘The Fence’, a traveling outdoor exhibition shown in seven cities across the country.

Galton has received many awards, most recently the Tokyo International Foto Awards, 12th Julia Margaret Camera awards, IPA Awards, Graphis, Communication Arts and the PDN Taste Awards. Galton lives and works in New York City.

Memory of Absence

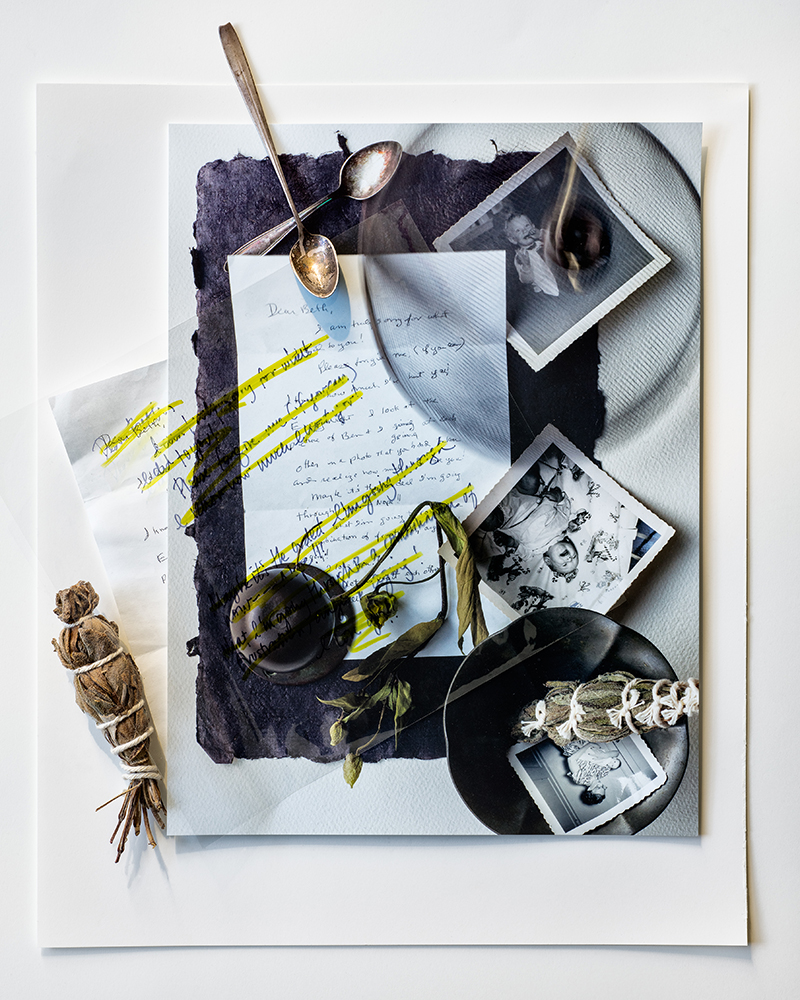

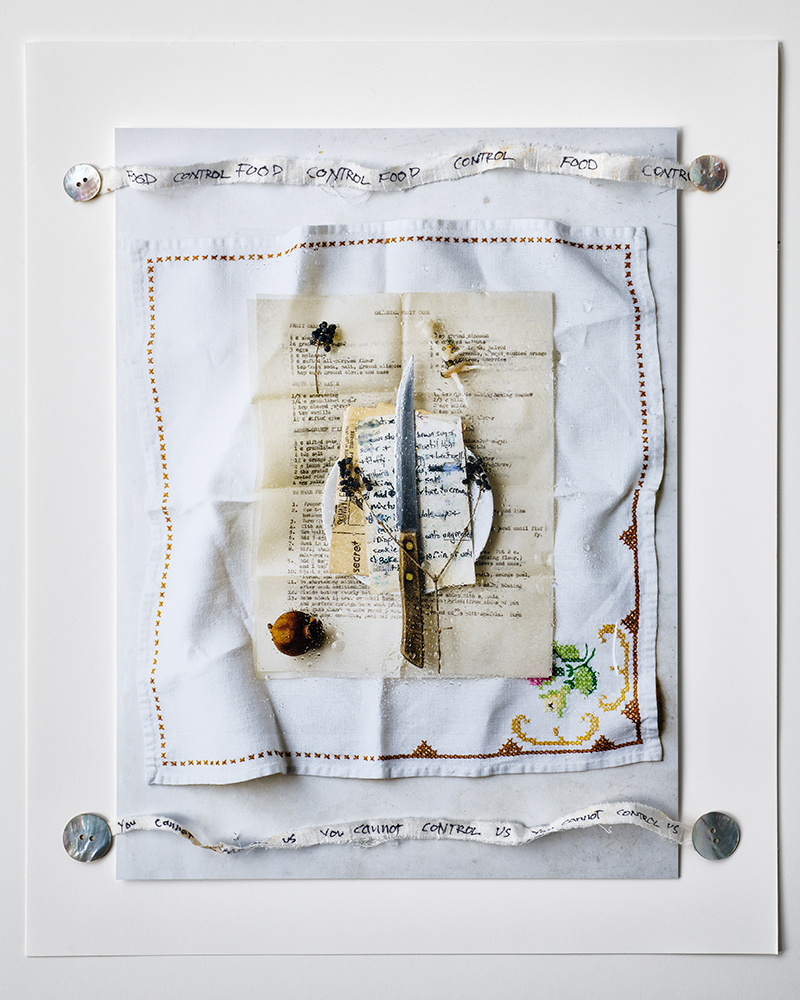

So much of who we are is passed from generation to generation—our genes, our behaviors—molded by our parents and grandparents. My mother’s relationship with her mother was fraught with difficulties and these same dynamics were passed onto me. I’ve spent many years contending with these issues by first becoming overly involved in my mother’s life and then ultimately removing myself. In 2017, my mother and father— who had not lived together for 50 years by that time—died within three days of each other. After my sister and I inherited my mother’s home we were startled to find the extent to which she had been hoarding. We discovered her journals, copious letters written to family members and never sent, and everyday objects and photographs depicting many family scenes that I have no memory of. A profound sadness combined with these surprising discoveries led to my creating this body of work exploring feelings, memories and even buried memories – all brought to the surface through these revelations.

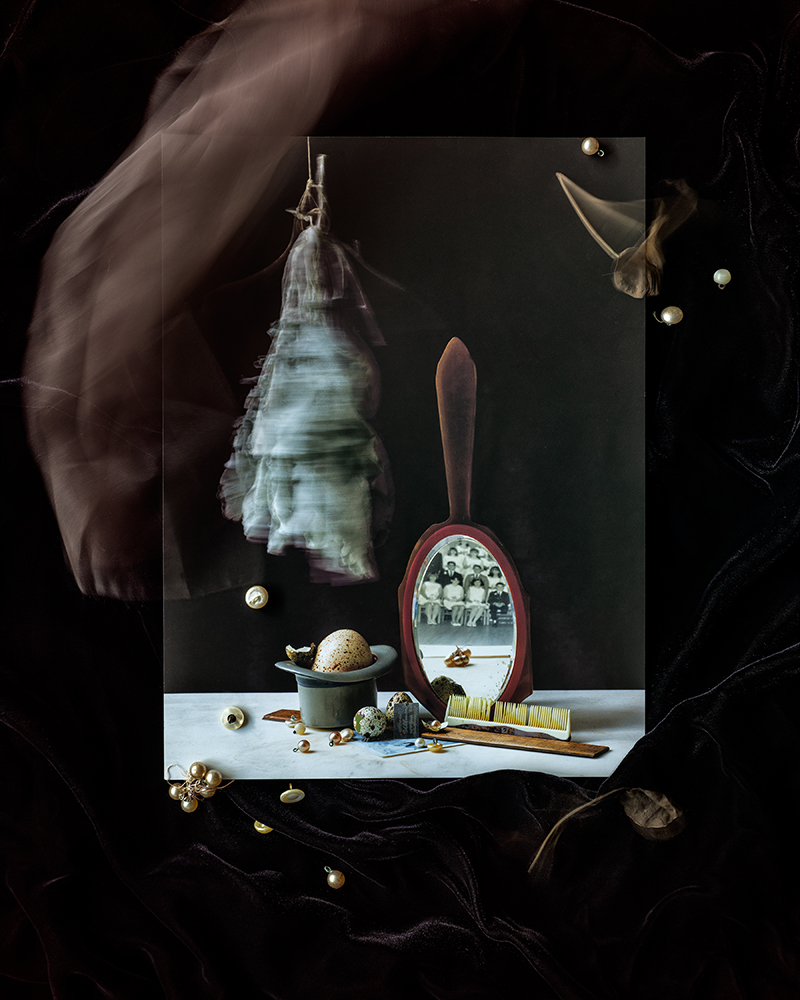

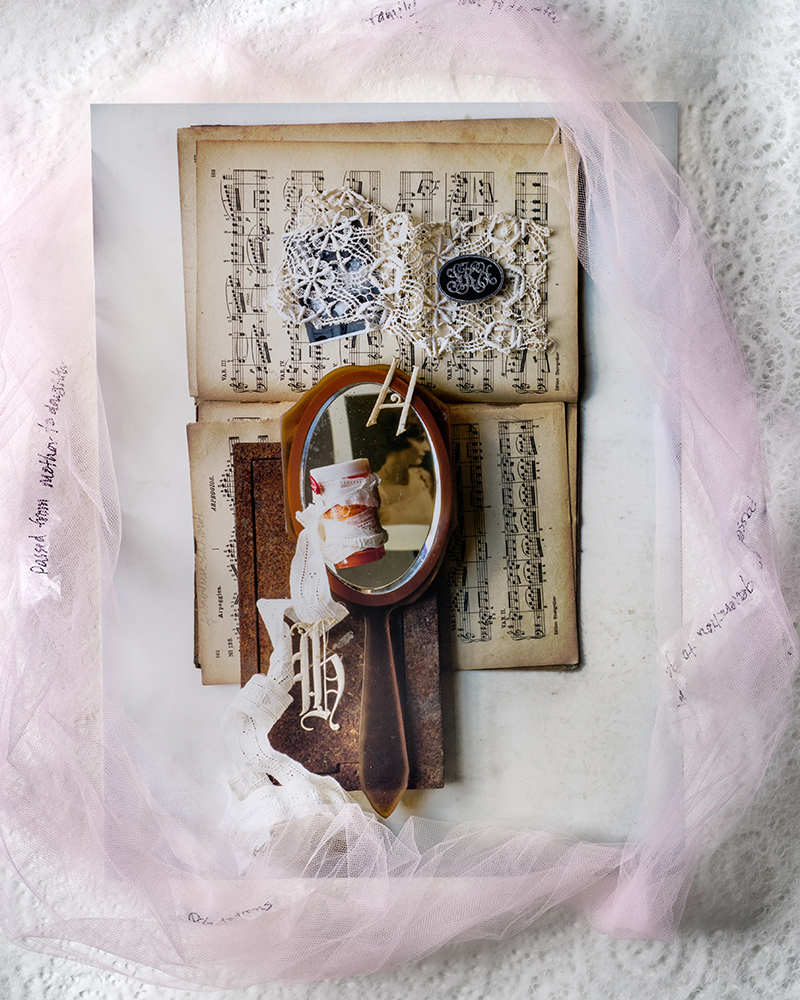

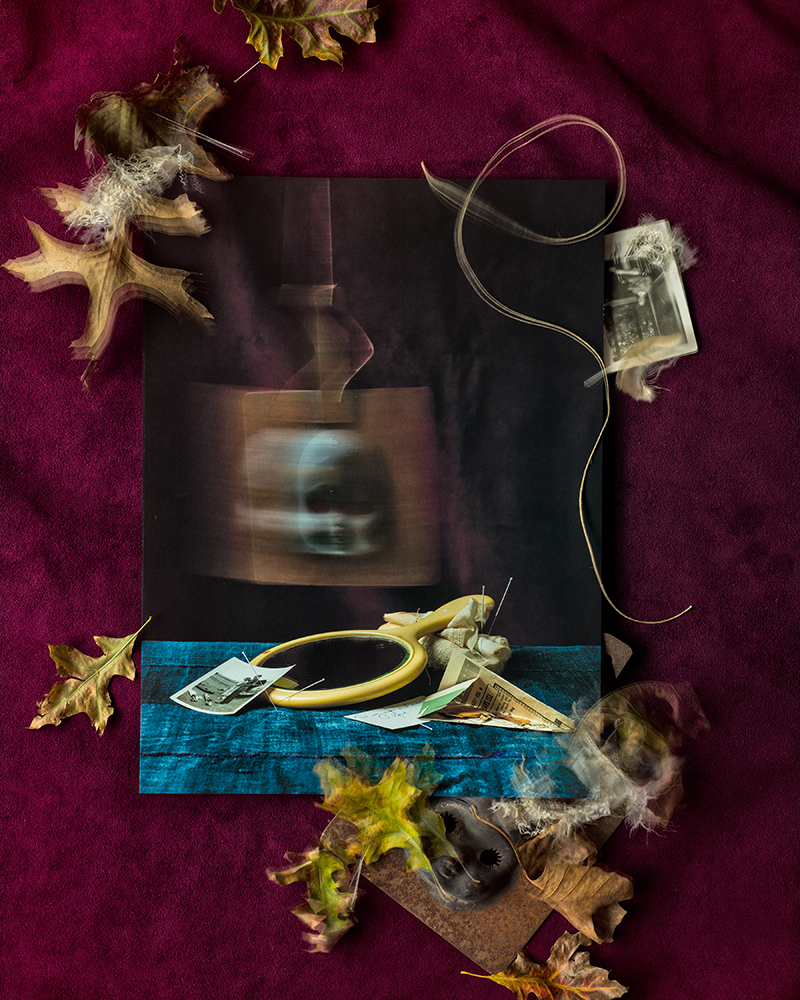

In this series, Memory of Absence, I combined botanicals and natural materials together with the everyday objects and family photographs in order to convey a sense of memory and loss. The organic and volatile botanicals serve as a reminder of the ever-changing nature of memory and emotions—an unstable and profoundly unreliable process, as fragile as scraps of embroidery as complicated and garbled as tangles of magnetic tape. Text plays a key role as well, her words intertwined with mine.

My creative process begins with composing and photographing a still life of the botanicals together with the objects that I have collected and saved from my mother’s home. I then print out the image and create yet another still life by layering more objects with the print and then re photograph this composition. Thereby giving a further sense of the complex and layered emotions found within family dynamics.

Daniel George: You work in still life both professionally and artistically. What do you find compelling about the genre—that allows for this sustained commitment?

Beth Galton: After graduating college with a major in fine art focusing on photography, I decided to explore the commercial photo world. At the time, still life photographers were more open to hiring a female assistant than other photographers, so I fell into that genre of photography. What I quickly realized was how much I enjoyed composing a photograph – the process of analyzing and arranging objects to convey an idea. I love the contemplative process of moving the subject matter around until it creates a composition that resonates with what I’m trying to convey. As much as I appreciate and study different photography genres, I continue to come back to still life for my own practice.

DG: You write that both the sadness associated with losing your mother, as well as discoveries made while going through her belongings were catalysts for making this work. I am interested in hearing your insights into the broader topic of using art to process grief.

BG: I had a very complicated relationship with my mother growing up, and spent most of my time navigating rather than reflecting on its nature. With her passing and the sorting of her belongings, it opened up a whole new avenue to process this important and difficult relationship. Creating these images has enabled me to confront and express many of my repressed emotions allowing me to explore and understand them more clearly. Now looking at this body of work I see that many of these themes are actually universal to family relationships particularly between mothers and daughters.

DG: So, this project came together as a result of you coming into ownership of a trove of materials in your mother’s home. With the vast amount of things that you had to work with, what was it about these specific items that spoke to you?

BG: As I created these images, I would look for objects that evoked a memory or emotion from my past with my family. Some of the images sprang from my feelings of anger, or a sense of great loss. I became very interested in what behavior and personality traits passed from generation to generation when reading notes and journals written by my mother about her mother. The discovery of photographs and letters that I had no recollection of, granted me the freedom to make up my own interpretations of what meaning they might hold. As time went on, I found I had also created images with a deep sense of love and gratitude for those family members who had left lasting memories and impressions.

DG: As I look at your photographs and consider the context in which they were created, my mind immediately goes to memento mori. And while they do not generate personal memories, they do prompt a reminder of the brevity of life, and perhaps my need to cultivate familial relationships. Because these images are so personal in nature, I am curious how you interact with them—particularly as time goes on.

BG: When I look at these images, a year and a half since completing them, they still bring up a host of feelings. It’s also interesting to see how these emotions have evolved. This process has helped me see where I come from, what traits I’ve inherited from my family, as well as the different paths I’ve taken to break some of the more detrimental family behavior. In many ways, they’re a document of my life, helping me understand the importance of family and their impact, allowing me to forgive and move on from my childhood. I have found the process cathartic, releasing me from many emotions I’ve carried throughout my life.

DG: Through these images, you are creating a story for future generations—where your memories and relationships with family will be continue to be legible. Why do feel photography was the medium best suited to accomplish this task?

BG: Since the age of 20 I’ve been a photographer, using photography to explore and express myself in the world. It seemed a natural extension to use this medium to examine the issues closest to home–the complicated family relationships in my life.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024

-

Interview with Peah Guilmoth: The Search for Beauty and EscapeFebruary 23rd, 2024