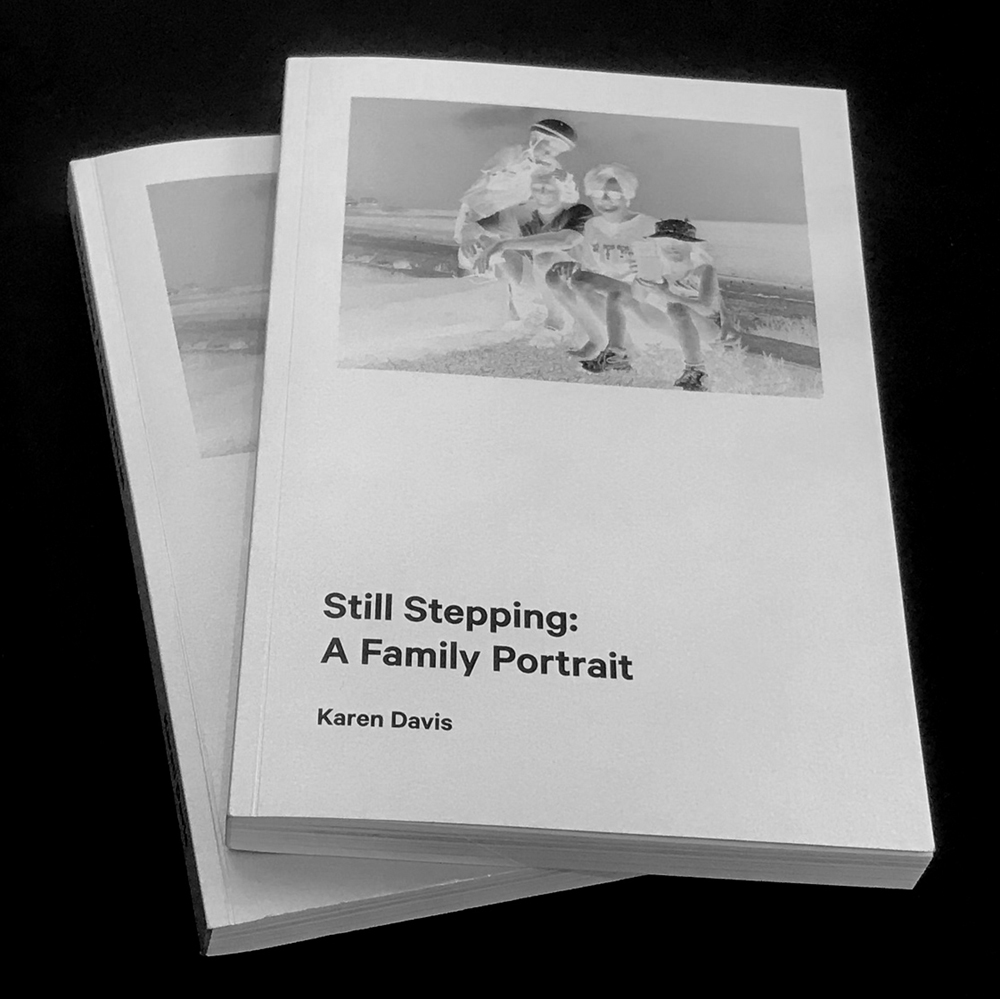

Karen Davis: Still Stepping: A Family Portrait

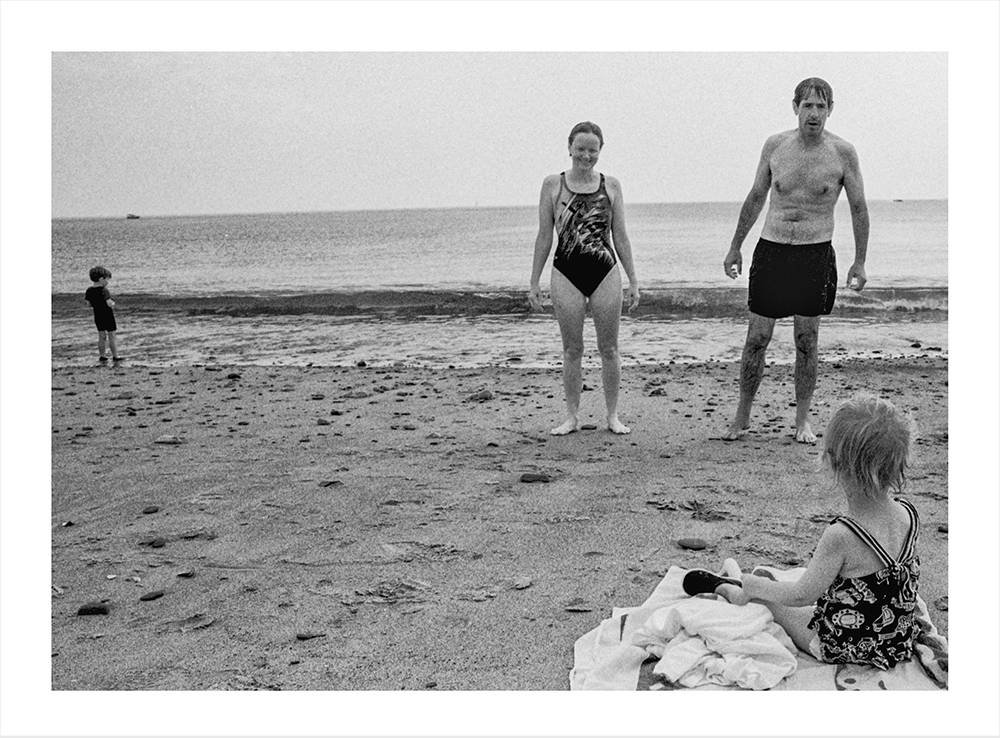

Twenty-five years ago, Meredith Morgan, Edward Orton and their children, Parker and Maggie, became the primary subjects of my photographic exploration of family. As a new photographer, related to them through marriage, I was grateful for their accessibility, openness and patience.

Still Stepping: A Family Portrait is the story of the Morgan Ortons as they cruise along, get clobbered by a devastating childhood illness – childhood onset schizophrenia (COS) – and then move forward. My photographs and the family’s words present a narrative of the family as their world turned upside down and was then righted by shaken but determined parents. Over the years, no matter what the circumstances they found themselves in, they wrote and I photographed, which now makes it possible for me to share their story. – Karen Davis

I have known Karen Davis since the early 2000s, when I attended my first Photography Atelier course, which she taught with the late Holly Smith Pedlosky. For me, her skills as an artist and a teacher are unsurpassed. As a teacher, she brings both a deep well of knowledge about photography and the compassion and open-minded critical eye to engage students and give them tools to generate and refine their work. As an artist, Davis experiments with her ideas and works intensely to shape her images and narratives.

In Still Stepping, Davis has integrated, in a remarkably fluid manner, word and image, a subject she has studied and taught. In the end, Davis’ portrait of this family is both absolutely unique and compellingly universal.

In her Foreword, Alison Nordström writes, “What sets this book apart, aside from its moving subject, is the collage-like form the narrative has been given by the juxtaposition of several different forms of communication.” These include letters, an essay, video transcriptions, interviews.

To build on this idea of collage in two additional ways: first, I see the text as the prose—providing much of the exposition, the explanation of events. The photography provides much of the emotional resonance—it’s the poetry. Second, Still Stepping works in the domains of both art and science. The book’s two introductory essays are perhaps the best way to lay bare Davis’ approach. The context of photographic art and history is provided by Alison Nordström, Ph.D. Her penetrating and perceptive essay places Karen’s achievement in specific photographic realms (family, word and image), and analyzes the photographs’ aesthetic features.

The context of medical research and treatment of COS is provided by Jeffrey A. Lieberman, M.D. He writes a deeply human essay about the family’s struggle with COS, with enough scientific information to give the general public an appreciation of the gravity of the disease.

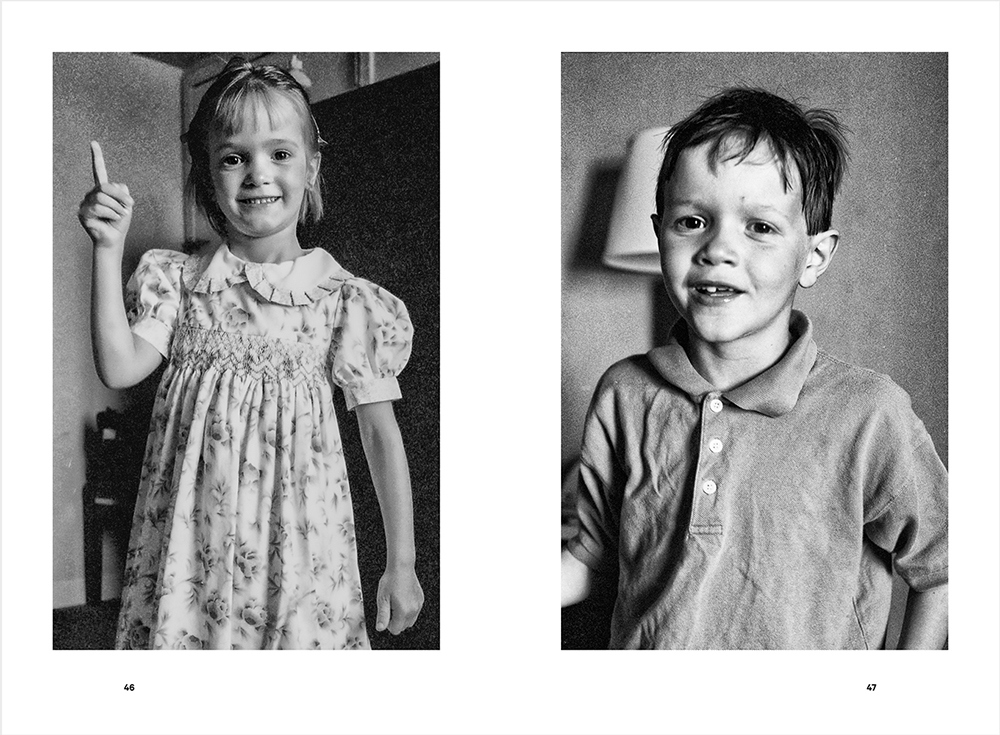

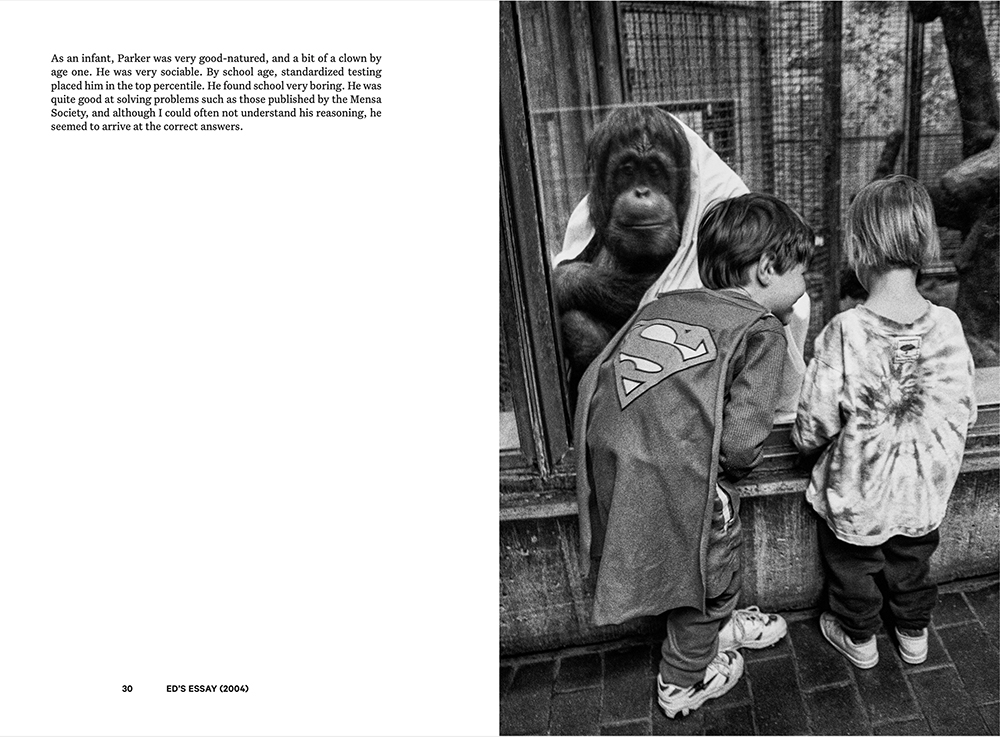

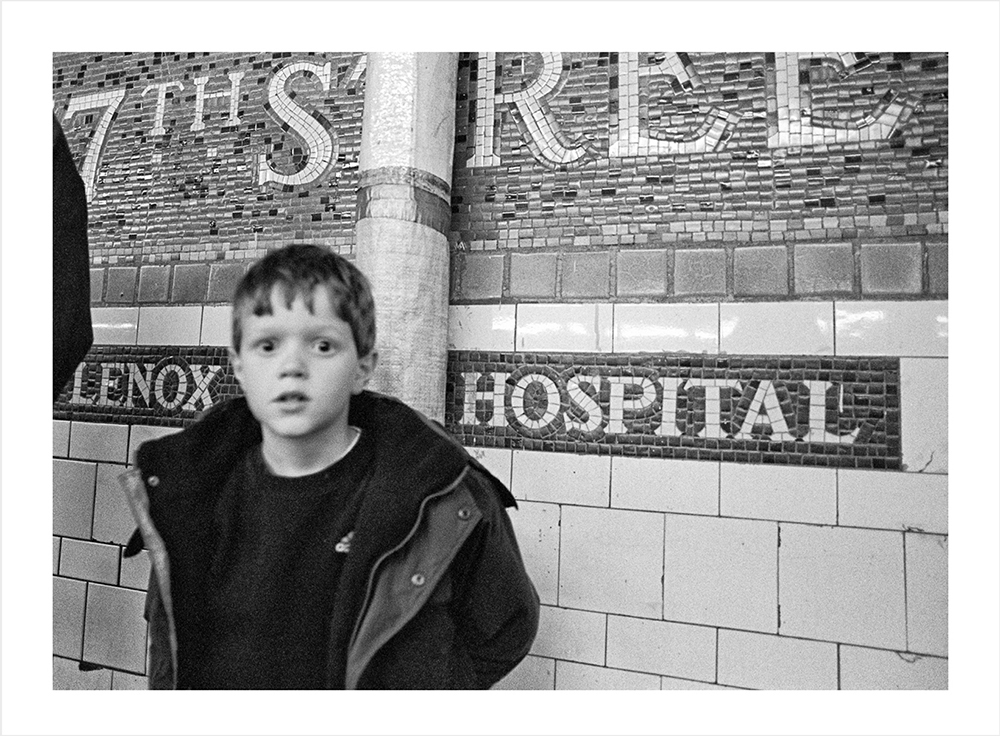

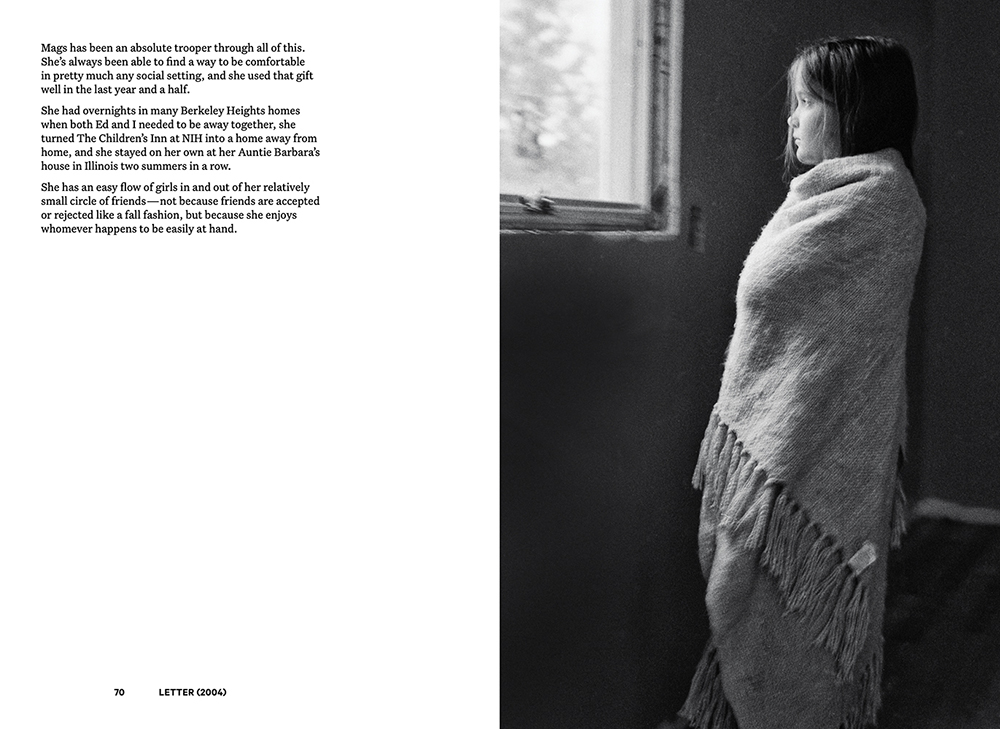

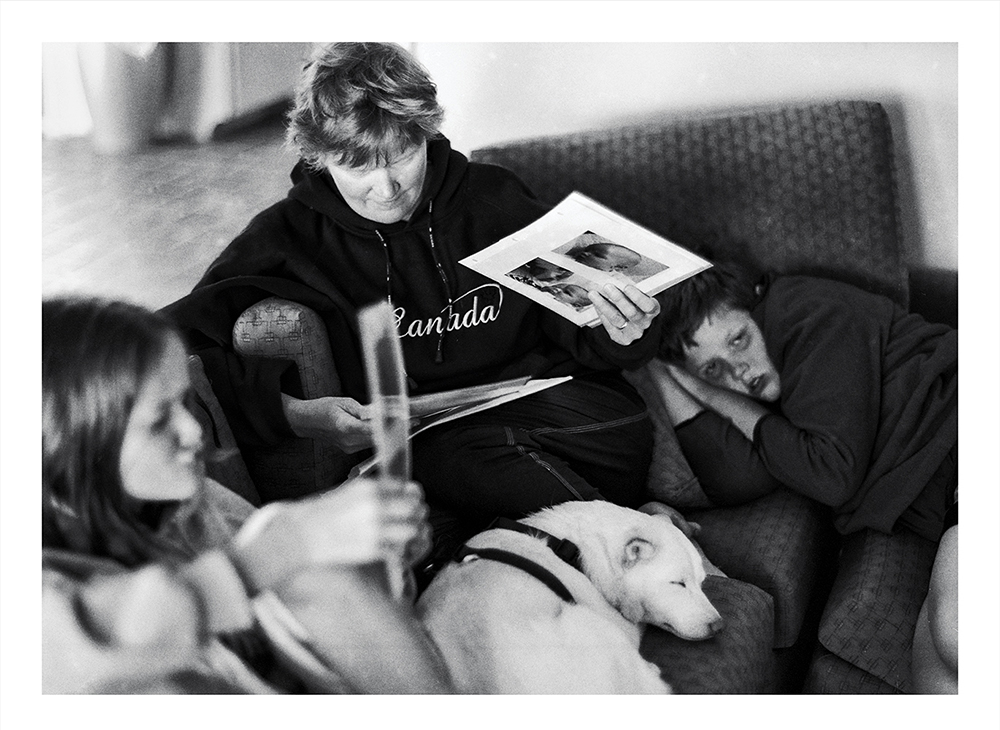

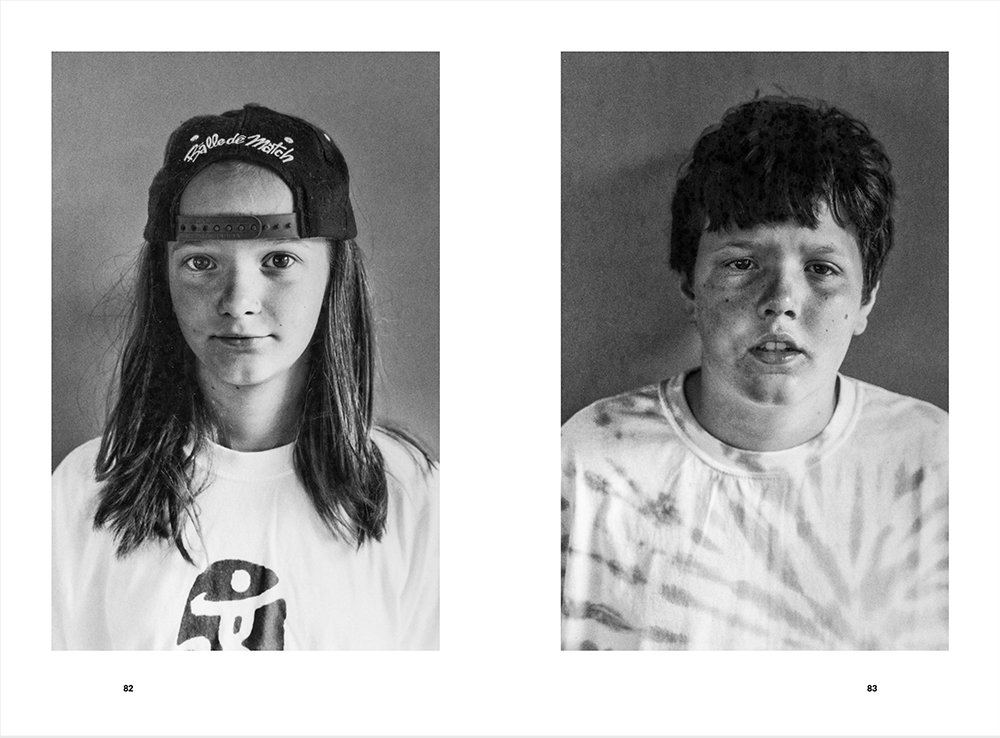

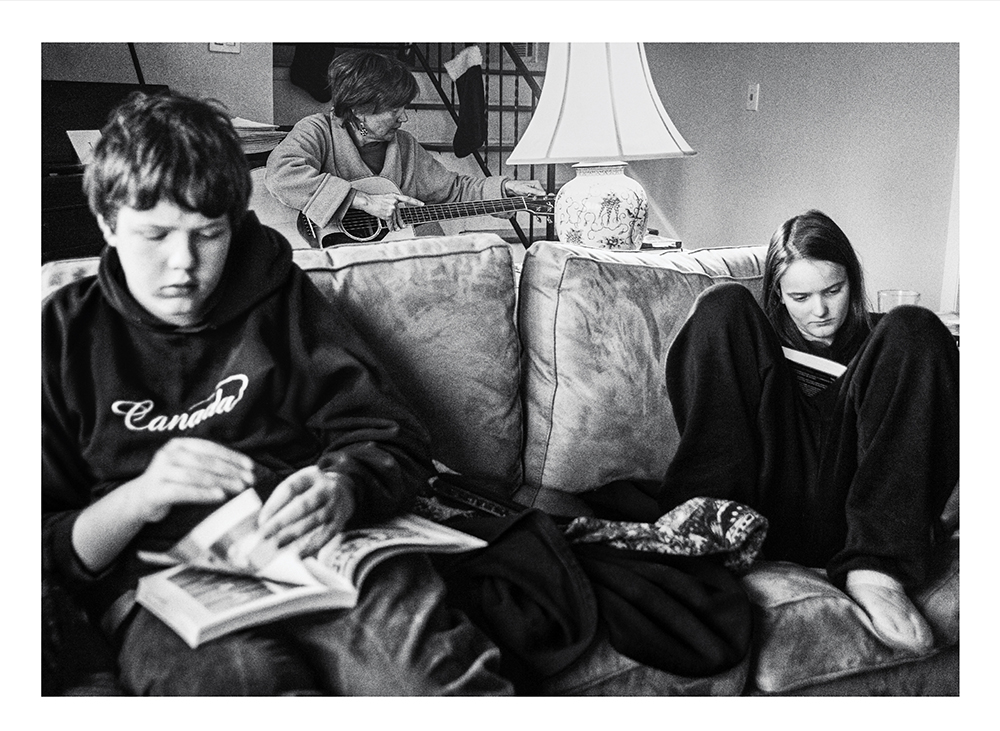

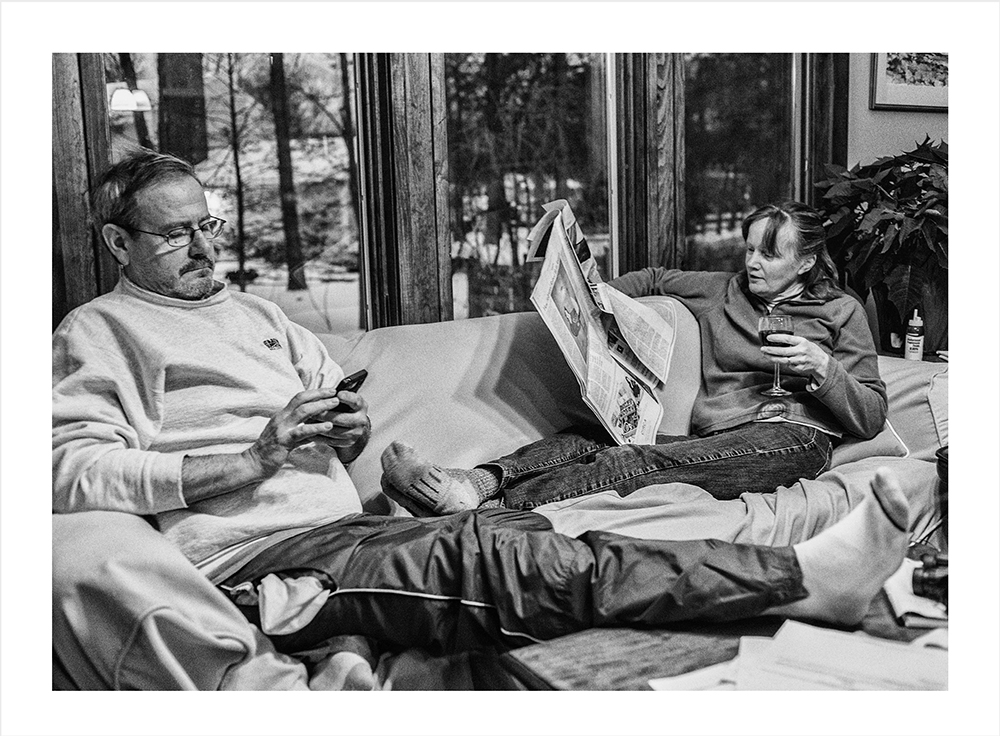

The photos center almost exclusively on the family of four. The images are invariably tight, varied in composition, perspective, and emotional tone. Davis’ camera is usually quite close to her subject, capturing limbs lovingly intertwined, with people engaged or distracted, joking or serious, and sometimes simply going through their ordinary daily routines with Davis capturing it all.

Davis has a deep understanding—enriched by years of teaching—of the photographic domain she’s working in. Her studio overflows with catalogs and monographs of photographers who capture family and friends. Some use a more formal compositional style, including Judith Black, Tina Barney, Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Others favor in-the-moment shots, such as Nan Goldin, Richard Billingham and Nick Wadlington. Davis’ work shows an appreciation of both approaches.

Karen Davis’s work is featured at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) and in the collections of Center for Photography at Woodstock (CPW) at Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art; Lishui Museum of Photography (China); Houghton Rare Books Library, Harvard University and corporate and private collections. Her word and image book, Still Stepping: A Family Portrait, was published in December 2020.

Karen Davis’s work is featured at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) and in the collections of Center for Photography at Woodstock (CPW) at Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art; Lishui Museum of Photography (China); Houghton Rare Books Library, Harvard University and corporate and private collections. Her word and image book, Still Stepping: A Family Portrait, was published in December 2020.

Davis, of Hudson NY, is a Critical Mass 2018 finalist and recipient of the 2009 Artists Fellowship Award-CPW. Her photographs and artist books have appeared in numerous solo and featured exhibits throughout the country. Her project, The McCann Family, was exhibited at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, MA; her series, Strangely Attracted, was featured in Exposure 2018, Photographic Resource Center, Cambridge, MA.

Davis is curator/co-founder of Davis Orton Gallery in Hudson NY, now in its eleventh year, where they exhibit photography, mixed media and photobooks. She was a longtime teacher of Photography Atelier which began at Radcliffe Seminars, Harvard University, continued at Lesley Seminars and now is at home at the Griffin Museum of Photography. She has taught other photo-based and word and image art courses at the Art Institute of Boston/Lesley University, Tufts University’s X-College and Suffolk University. Davis presently teaches Portfolio Development and Marketing online for the Griffin Museum.

Ellen Feldman: You had been photographing the Morgan Ortons, your husband’s brother’s family, for over two decades when you decided to make a photography book about them. At some point in the development, you decide to include text.

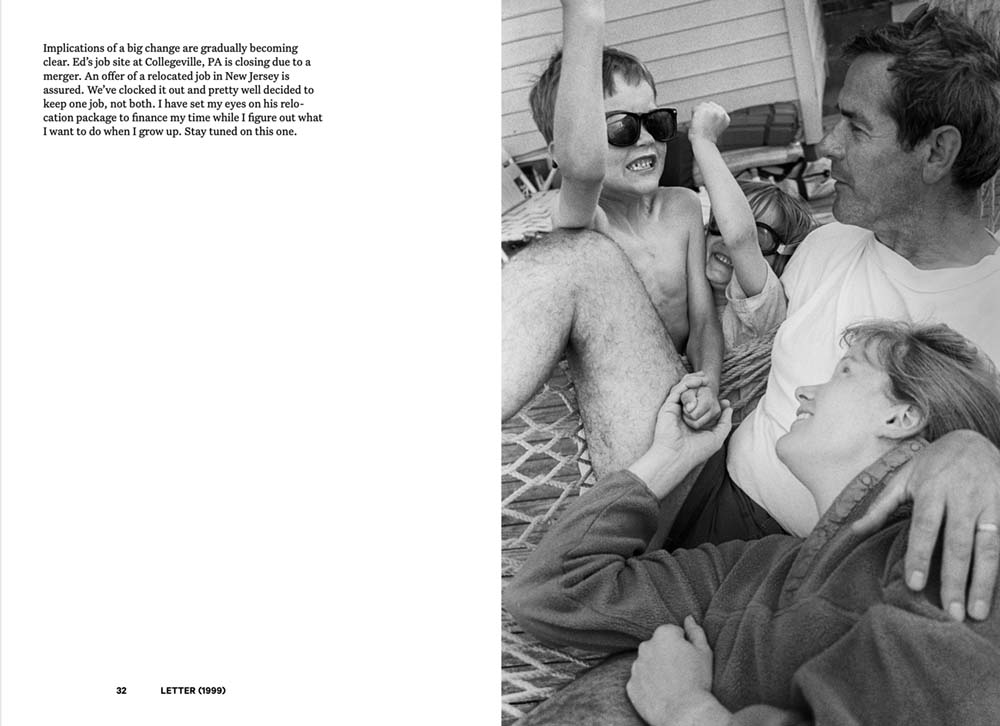

Karen Davis: Text and image are two ways to tell a story. I came to believe the inclusion of text with my photographs would be critical to the story and enrich it. It certainly did, but I struggled to find the best way to incorporate the material. Separate volumes for text and photos? Snippets of text signaling a new section of photographs? Snippets and including three or four of the actual letters? I tried and rejected these ideas. The search for a solution to the use of text consumed many iterations and a lot of trial and error. In the end, the text became a partner to the photographs in the narrative.

EF: How about the photos? I don’t imagine the selection and sequencing were easy.

KD: That’s right. I had hundreds—if not thousands—of photos to work with. I could do the initial culling, but I realized I needed help. I had two remarkable consultations with Sylvia Plachy, whom I had studied with years before. She asked me to bring lots of paper clips and small photocopies of my images, the equivalent of eight per page, cut up, and over a few hours we made selections. Then she assembled and reassembled photos into a kind of accordion book. At the end, I had my road map, which served me well for the rest of the project.

EF: You didn’t change or rearrange photos after that?!

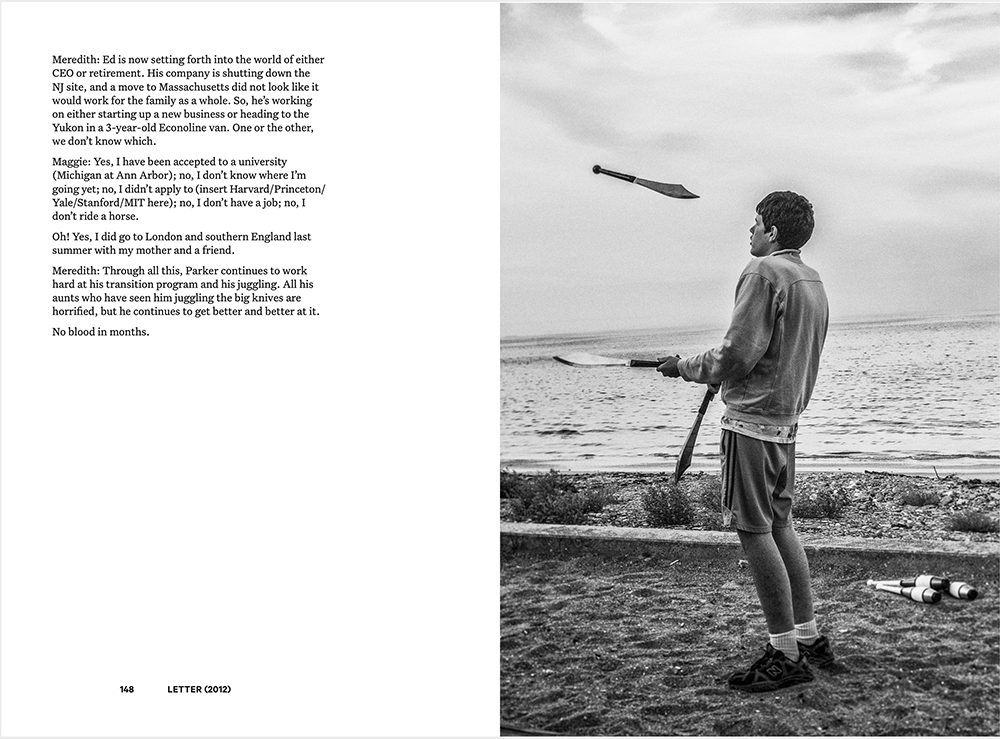

KD: Oh, I made many adjustments along the way. To give just one example: Someone in my critique group observed, “Parker doesn’t look sick.” That is the reality—mental illness can be an invisible disability. Although I had included photos of him in the hospital, I also had photos of him skating and playing chess and horsing around. I added two or three photos so we wouldn’t forget the seriousness of his medical condition.

EF: How did you come to use a portrait orientation for the book?

KD: I knew from the start that I wanted to use a vertical format—I wanted it to be, even with many images, a book to be read—since this is a story in word and image, rather than a book of individual photos, as Alison Nordstrom discusses in her Foreword.

EF: Setting aside the oft-said but limiting argument that documentary, socially conscious photography punches more power in black and white, why did you decide on grainy black and white images. And why use the photo in negative of the family for the cover?

KD: This was another major decision for me. I liked the look aesthetically, but it also resonates on a personal, rather nostalgic level. When I started out as a photographer, which was around the same time I began photographing the Morgan Ortons, I mostly used Tri-X [Kodak black-and-white] film in available light, so the results had a tendency to be grainy—an effect I liked. I wanted all the photographs in the book to have a consistent appearance so I decided to emulate the look of Tri-X which meant converting color film and then digital images into black and white with a touch of graininess.

As for the cover, I created a few versions, but when I saw a silver cover with a black and white photograph that, of course, translated to black and silver for the catalog by 10×10 Photobooks, How We See: Photobooks by Women, I decided to “borrow” the idea. But I found that using a negative image, instead of a positive one, was even more powerful.

And I cannot leave out Christine Labey of Conveyor Studio who was responsible for the final design of the book, including the important details of page structure and navigation, the look of type and photographs on a page, the options for cover material and paper stock. Conveyor Studio also printed the book and was great to work with.

EF: The Morgan Ortons let you freely photograph them. How did that work?

KD: Probably because I was a photography student [at NESOP, the New England School of Photography] when I began to photograph them, they were totally forgiving, as we tend to be with family members working on school projects. In a way, I honed my craft and my art photographing them. I became virtually invisible, even when following them closely as they moved around.

Tech details: I mostly used a fixed/prime 35mm lens, a lens that closely approaches the human eye’s vision (which is actually 43mm). I shot in available light, often in low indoor lighting, so I needed as fast a lens as possible. My 35mm lens is 1:2. When I needed a faster lens, I used my 50mm 1:1.4 lens. That said, with digital images, I could set the film speed higher than the 400 ISO film I used in color and black and white.

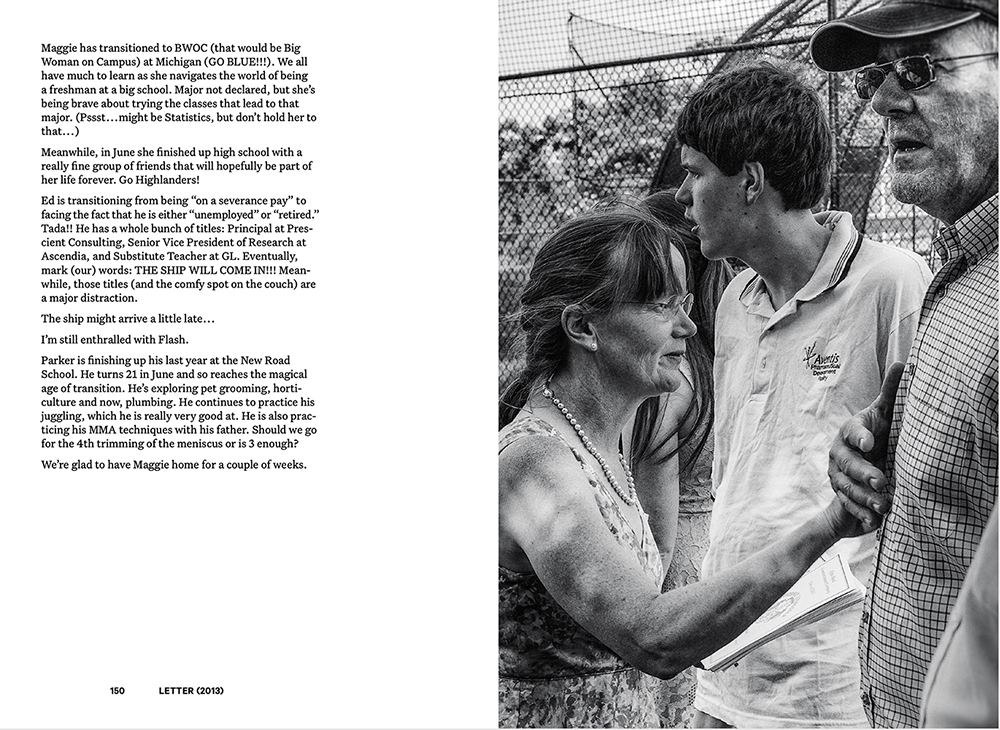

EF: You were fortunate to have lots of texts—mostly letters—by the parents, both smart, articulate, witty, and succinct writers! How did you decide what to include—and exclude—from this wealth of material?

KD: As with the photographs, I selected text that dealt with the four Morgan Ortons and excluded details about friends and relatives, vacations, and so on. I did want the book to include humor which is a strong family trait, and the letters provide that in abundance. To call attention to the seriousness of Parker’s illness, I incorporated excerpts from an essay by Ed Orton, “A Father’s Perspective on His Son’s COS,” and the parents’ words in the video, “Childhood Onset Schizophrenia,” co-produced by the Montefiore Medical Center and WNET.

And finally, when Alison Nordström, who wrote the book’s Foreword, read a late version of the book, she told me that she missed hearing more from the daughter. That lead me to conduct separate interviews with Maggie and the other family members. By that time, 2017, they could take the long view of their experiences—peeling back the layers to reveal something not evident in the midst of their journey. That is how the Postscript came to be.

EF: Your interview with Parker is especially moving—it shows, as much as your images of him, his difference from the other members of this exceedingly verbal family.

EF: Let’s put it all together. This is a portrait of a family in word and image. You developed and taught a Word and Image course with the late Miriam Goodman, which you later taught with Cassandra Goldwater.

KD: That’s right, and one of our favorite teaching texts, which illustrated the different ways words and images work together, was Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, by Scott McCloud, a renowned writer on the art of comics.

Word and image are two distinct ways of “telling.” In Still Stepping, they are interdependent—where the words and images convey an idea that neither can convey alone.

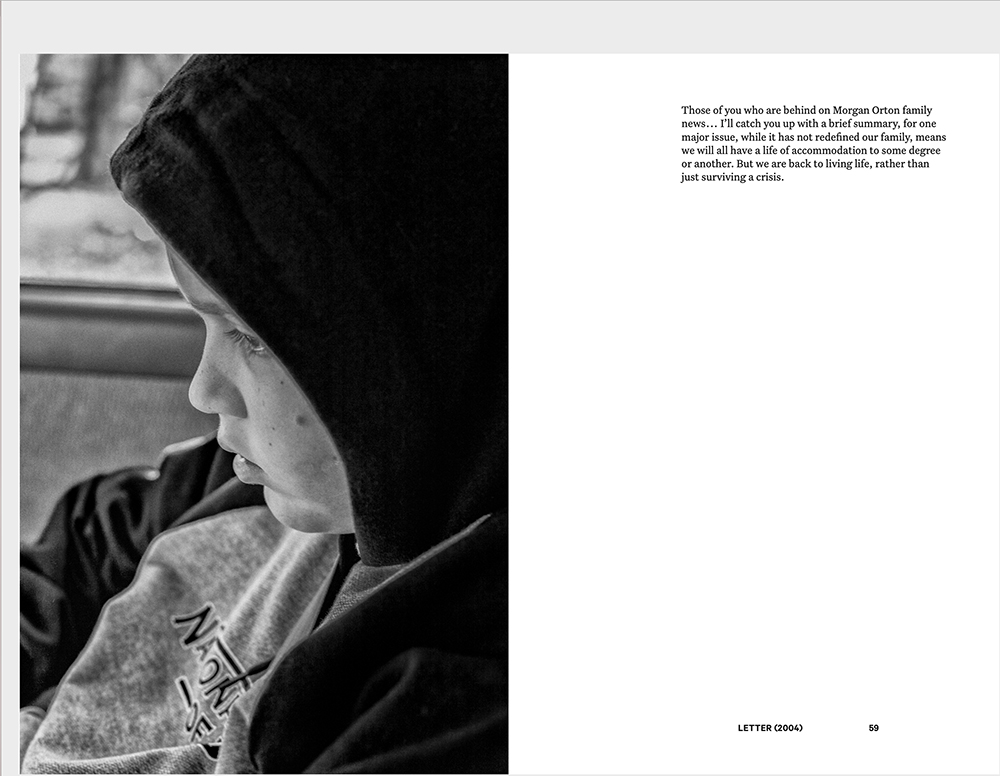

At times word and image converge in a subtle, indirect way. For example, the 2004 letter says, “[One] major issue…means we will all have a life of accommodation to some degree or another.” On the facing page, I place a photo of Parker, who’s not mentioned in the letter, looking down with a distant expression, most likely in the midst of an auditory hallucination.

Over the years I’ve collected word and image books of family/people close to home. Two of my all-time favorites are Dorchester Days by Eugene Richards and Pictures from Home by Larry Sultan. I suppose, if nothing else does it, I’m dating myself with my list of favorite artists and titles, but while I’ve added to my list over the years, the artists mentioned here and in your introduction remain among my favorites.

EF: Still Stepping will, I imagine, draw several distinct audiences. Were you thinking about the book’s readership as you were developing it?

EF: Still Stepping will, I imagine, draw several distinct audiences. Were you thinking about the book’s readership as you were developing it?

KD: I made this book to tell the story of this one particular family, the Morgan Ortons, who faced their child’s treacherous mental illness and learned to move forward. As one reader wrote to me: Still Stepping is about “very ordinary and remarkable people.”

Now I see the book might interest a wider variety of communities beyond those I first thought of –photographers, artists in word and image and the wide audience who follow photography, love photobooks, as I do, and word and image art in all its forms.

It will most obviously resonate with families who have members with grave mental and physical disabilities. In fact, now that the book has been published, the Morgan Ortons want to participate in any way they can, believing that Still Stepping can help eliminate the stigma of mental illness.

The circles expand beyond those most directly affected, to those who interface with these families: friends, neighbors, mental health professionals, medical personnel, teachers, school counselors, home health aides, among others. The outer circle is, I suppose, the general population, with their stashes of family photos in closets and drawers and family-centered novels and memoirs on their bookshelves.

EF: The endorsements included at the end of your book come from people who read your book before publication. They belong to one or more of these audiences.

KD: Yes, I am grateful to the people, prominent in a range of fields, who endorsed my book. They include artists, curators, and writers in media and the arts such as Shelby Lee Adams, Paula Tognarelli, and Elin Spring. On the topic of schizophrenia, they include writers, physicians, therapists and also someone affected by schizophrenia, including Siddhartha Mukherjee, Harold Koplowicz, and Linda Larson.

EF: You had a sister with a disability…

KD: Yes, and if there was one propelling situation that planted a seed for this project, it was probably my own nuclear family: my late younger sister had a severe physical disability. I have only gradually come to realize how much my family situation influenced the creation of this book.

If I’ve succeeded with Still Stepping, it’s because I’ve managed to portray a family, not just a son/brother with a disability.

Ellen Feldman is a fine art photographer who has exhibited widely. She is also co-curator, with Marky Kauffmann, of the traveling exhibition, “Moved to Act,” photobook author of “We Who March: Photographs and Reflections on the Women’s March, January 21, 2017” and photography editor of the Women’s Review of Books.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026