Poland Week: Mikołaj Grynberg: AUSCHWITZ – What Am I Doing Here?

©Mikołaj Grynberg, -In my country a great surge of hatred is rising. That’s why I came here. – What will you do with this? – I don’t know, but I am terrified it can end up like this.

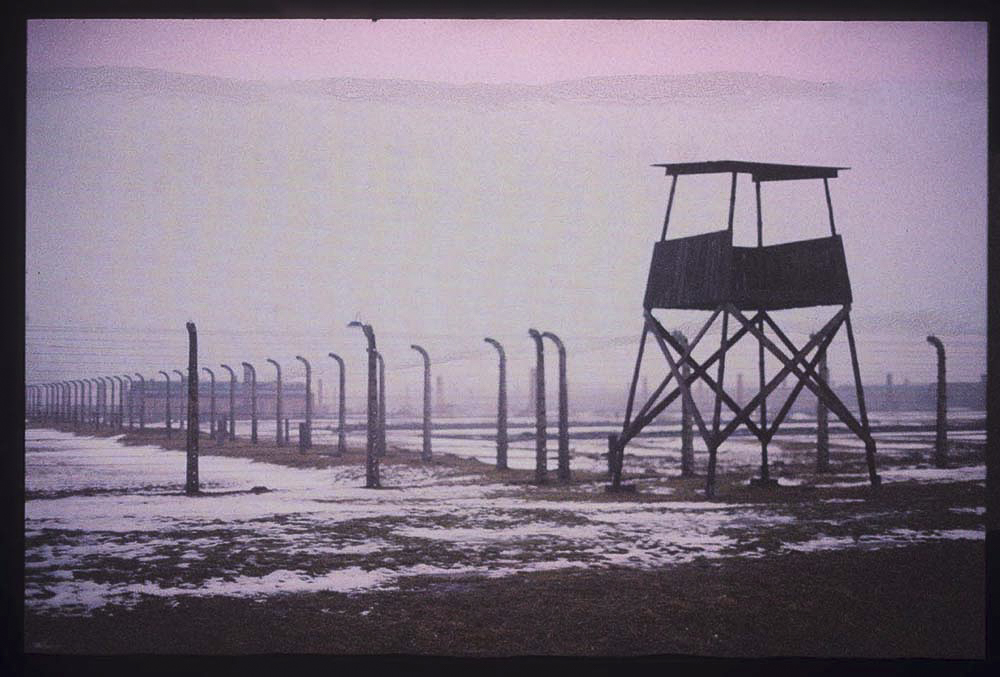

Having lived in Poland for two years during the early 1990’s and having been raised with pronounced Jewish influences from my mother’s side of the family, I felt compelled at that time to visit the remnants of the scene of horror that was Auschwitz, the infamous Nazi death camp, situated in southeastern Poland. I visited the camp as a “tourist “which made me all the more interested in Mikolaj Grrynberg’s powerful photographic essay on Auschwitz that poses both the existential and personal question…what am I doing here? Grynberg’s premise was to ask people visiting Auschwitz why they chose to come to such a place. In so doing, he photographed both the visitors and the camp in a gauzy haze of soft focus and recorded the varied responses that he heard. The project was his means of coping with an abiding fear of the camp connected to the tragic fate of his immediate family. But the project also serves the purpose of reminding the world that it all too easy to forget what happens when we let down our guard, when we ignore the seeds of hatred and when we refuse to challenge what we know to be wrong. In an age of rising nationalism it is never too soon to sound a cautionary alarm which is precisely what Grynberg achieves with this psychic exploration.

©Mikołaj Grynberg, When I showed this photo to my friends they said: “It could have been my children’s clothes”. Yes, those were somebodys’ childrens’ clothes.

In describing the essence of the project, Grynberg states that: “Photos were an excuse for me. I was visiting Auschwitz to talk. I was telling people that I was a photographer and I take pictures, but this time, contrary to my other projects, photography is not very important. The central element is the experience. I was not afraid of emotions and I wanted more and more of them. Despite appearances, my aim was not to re-channel the trauma, but to open it.” Despite his intentions, there is an eerie underlying anguish on the part of the viewer in the blurred images that are a critical aspect of this series of experiences. The interview excerpts that are randomly partnered with the images of those visiting the camp further provoke somber reactions.

©Mikołaj Grynberg, – I can’t think in here. I can’t do anything here. – Why? – I’m crying all the time. I’m afraid it will be like this for the rest of my life, that I will never forget.

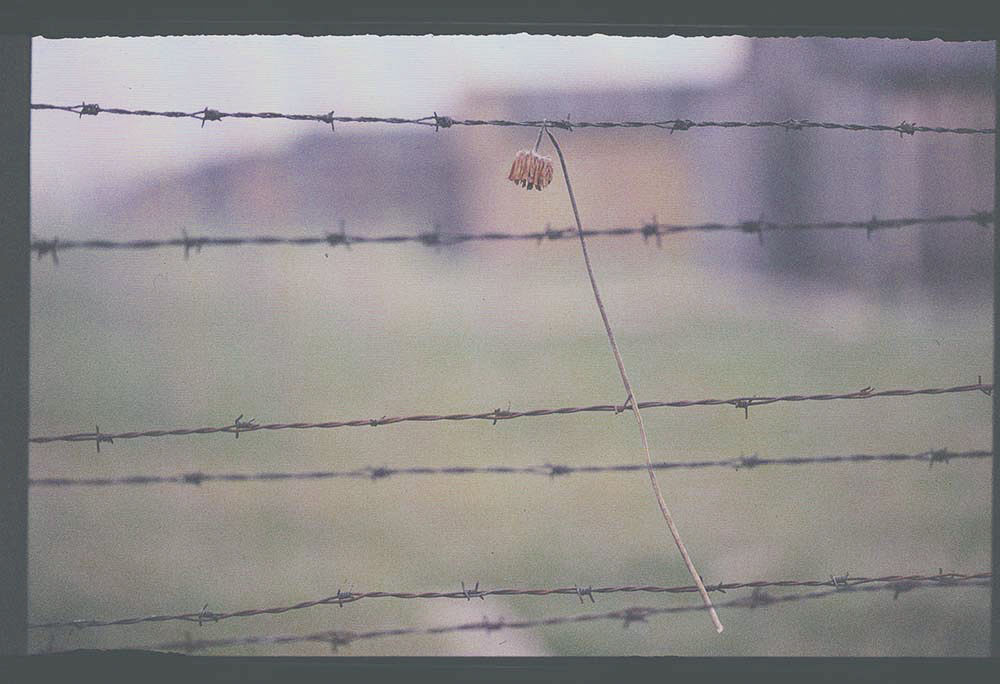

Another interesting observation concerns Mikołaj Grynberg’s choice to blur the images of those he photographed as well as the scenes of the camp, itself. He had access to parts of the camp that a tourist might never see including a disturbing view that the camp overseers would have had in the tower over the train tracks literally depicting the end of the line for the arriving Jewish victims. According to Grynberg, “I wanted to avoid the obvious, and so I decided to take photos of the things less sharp, of details. The idea behind this is the fact that the prisoners were rushed somewhere all the time and did not have time to look around. So I show parts of the image, of what an eye could catch. The photo of the infamous gate depicts only a part of the inscription, but the most wicked one: FREI. When, at one point, I thought I began to understand what happened there, I felt I was going insane. How can one understand that someone invented a way to kill more than a million people? How can you comprehend the factory that was founded there? What is impressive in Auschwitz-Birkenau is its gigantic area. It is a place where you understand the camp was a faultless factory – I have never seen anything like this in my life…full re-cycling of everything, even human ashes used as fertilizer, etc.”

©Mikołaj Grynberg, Behind this pile of glasses I saw all these eyes. What to do to protect them from being forgotten?

Grynberg also relates the moving story of his grandmother as a survivor of her experience at Auschwitz: “My Grandma was a pharmacist by education. As I described in the book, a question asked on the ramp upon arrival in Auschwitz was whether anyone was a doctor. Grandma’s friend, Doctor Slawka Kleinova, raised her hand, and after a while also raised the hand of my Grandma. Both were sent to the Hygiene Institute, where they filled out paperwork. This is how she survived the camp, then she went through the entire Death March from Auschwitz to Neustadt Gleve, where she was liberated by the American army.” Camp prisoners who were specialists in bacteriology, pathological anatomy, biology and chemistry from all over Europe were employed to do most of the lab work. Records indicate that the Hygiene Institute also produced trial serums and tested chemicals and their effectiveness. Additionally, the bacteriological laboratory tested the preparation of cultures on the basis of human tissue, using tissue from the thigh muscles and abdomens of the victims of execution.

©Mikołaj Grynberg, : – My grandfather survived the camp. – Is he still alive? – Yes. – Does he know you came here? – He does. – Did he tell you anything before you left to come here? – Yes, to see what I have to see and to try not to feel a thing. – And, will you follow his advice? – Yes, otherwise I won’t be able to cope with it.

I asked, Mikołaj why he has not photographed with the same vigor since the publication of the book on Auschwitz in 2010 and whether he has lost interest in photography as an artistic or socially conscious medium. His reply was: “After working on this project, I felt that photography had narrative limitations that would prevent me from telling the stories. I do not evaluate my actions. However, it is easier for me to talk about the motivations for the actions taken. The main reason is to share stories that not everyone has access to. This is how I perceive my role as the heir to these events.”

©Mikołaj Grynberg, Children’s block. In winter those who chose to sleep at the bottom were dead. by morning

Mikołaj Grynberg is a photographer and writer with a background in psychology. His photographs have been exhibited worldwide and explore elements of identity, memory and history. He is the author of the photo books Many Women (2009) and Auschwitz—What Am I Doing Here? (2010); the documentary books Survivors of the 20th Century (2012), I Accuse Auschwitz: Family Stories (2014), and The Book of Exodus (2018); and two short story collections Rejwach (2017) and Poufne (2020). His written work focuses on the experiences of Polish Jews in the 20th century through dialogue. He currently leads photographic and writing masterclasses and resides in Warsaw.

©Mikołaj Grynberg, – It’s a very personal journey. My father survived the camp as the only member of our family. – Have you found his traces here? – I found a suitcase with our surname. I can’t stop thinking that now we can come here and leave, and nothing happens.

©Mikołaj Grynberg, Something that irritated Survivors visiting the camp years later: “There was no grass here, just mud everywhere”.

©Mikołaj Grynberg, – I felt the genius loci. – How is it? – It’s incomprehensible. I saw drawings on the walls in the death cells. They depict smiling people. I don’t understand anything anymore.

©Mikołaj Grynberg, – If someone had told me about the conditions under which the prisoners lived, I would have never believed it. And now I don’t know how to believe it.

©Mikołaj Grynberg, The only photo of the gate I have taken. The complete inscription is on photos taken by every visitor to the camp.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026