Text + Image: Krista Svalbonas: Displacement

A month or so ago, I had the good fortune to experience the work of Krista Svalbonas in person, at Marshall Contemporary in Los Angeles. Two years ago, I viewed it briefly at a portfolio walk during FotoFest, but appreciating it on the wall, with good lighting, brought the work to life. These delicate constructions need to be appreciated in person–the shadows of the text and architecture are a big part of the experience of understanding how fragile the work is. This week we are exploring projects that include text and image and Svalbonas’ project, Displacement, marries these two elements so beautifully, resulting in work that is profound and weighted in history. Through the materiality that is at once lace-like and fragile, Svalbonas’ subject matter brings a weight and gravitas to her constructions.

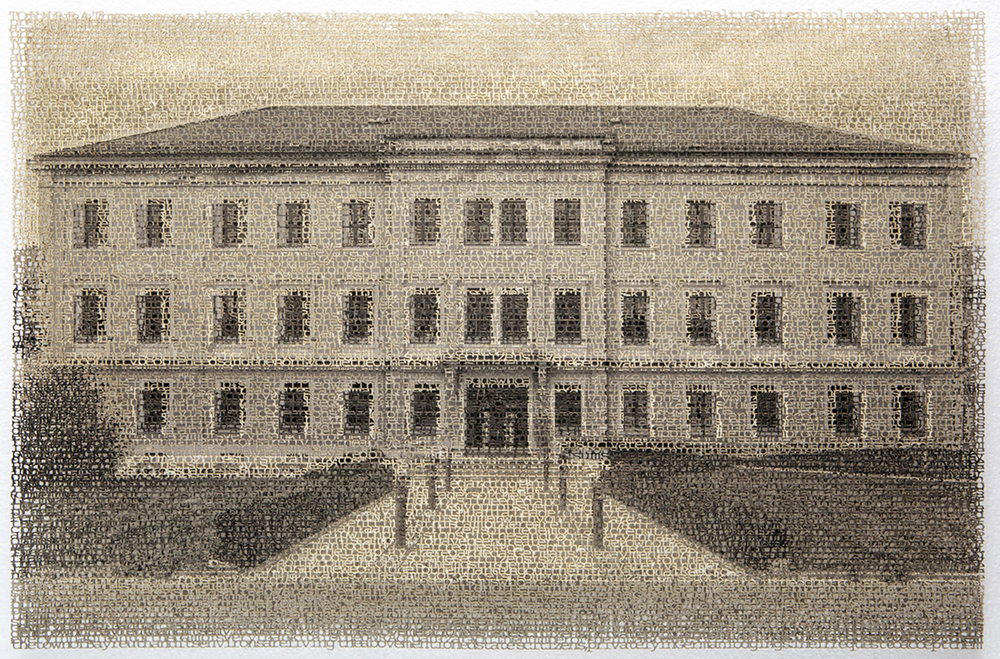

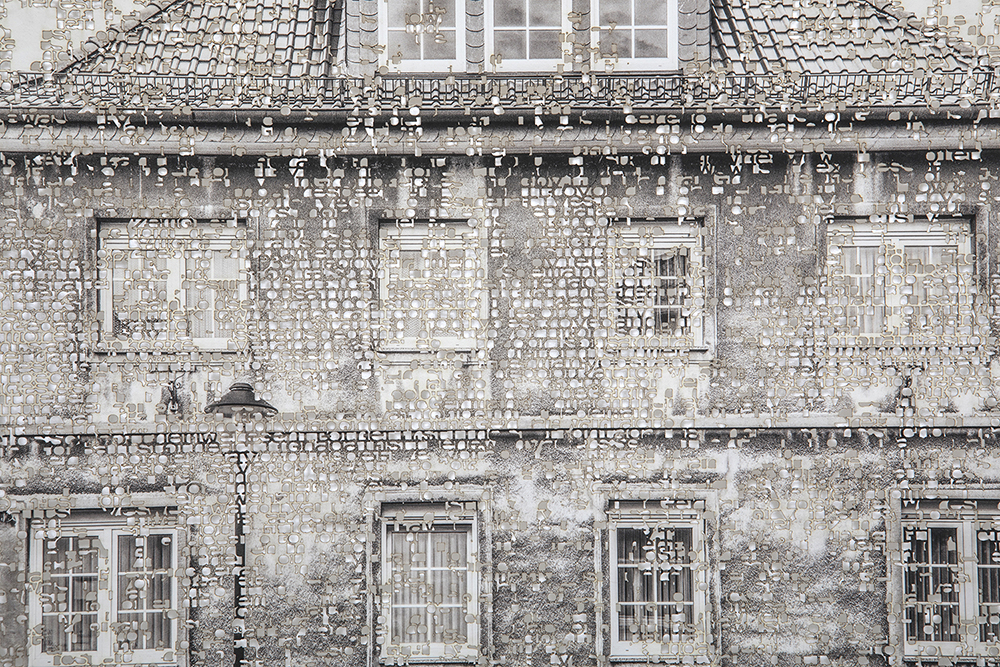

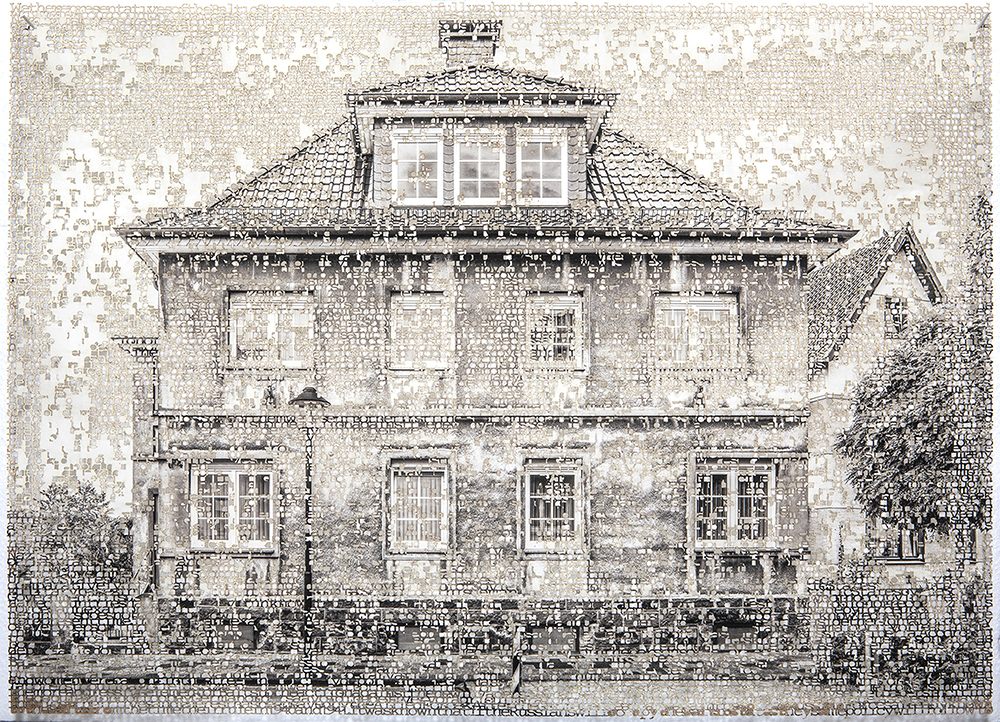

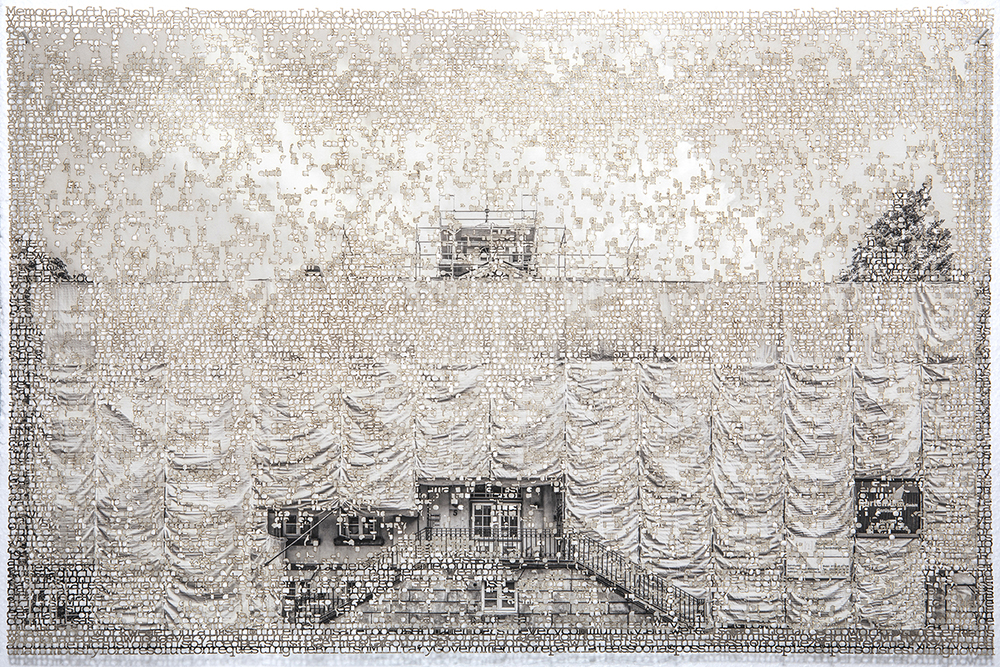

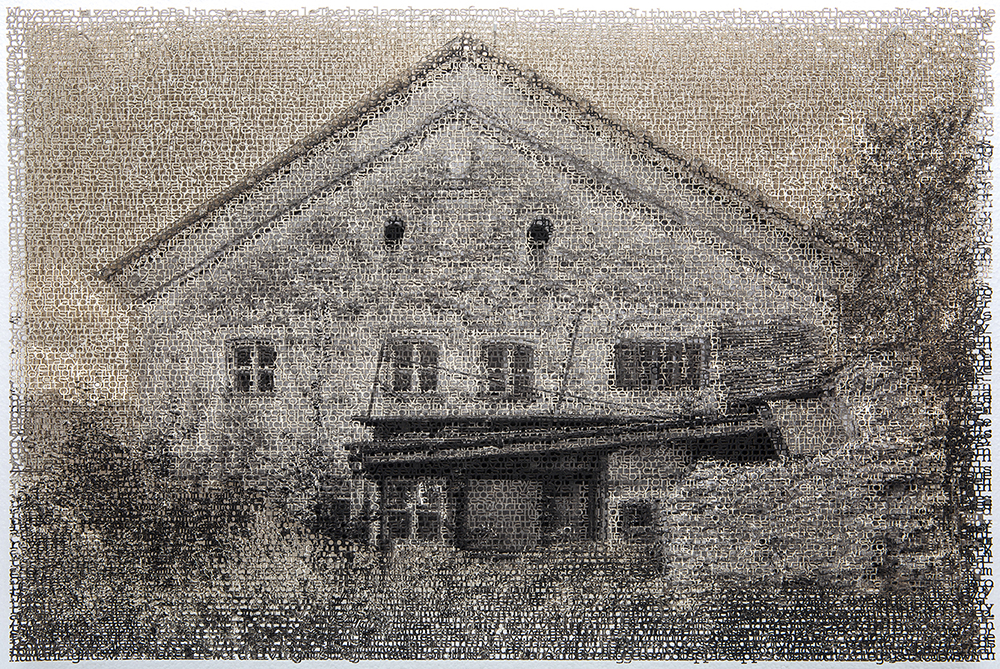

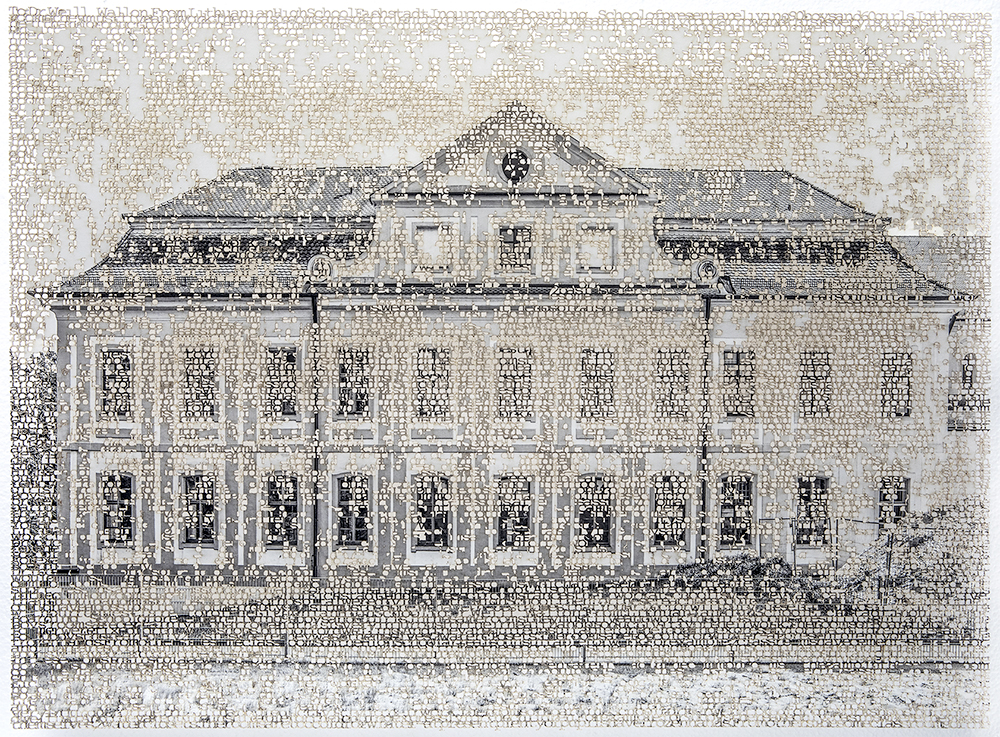

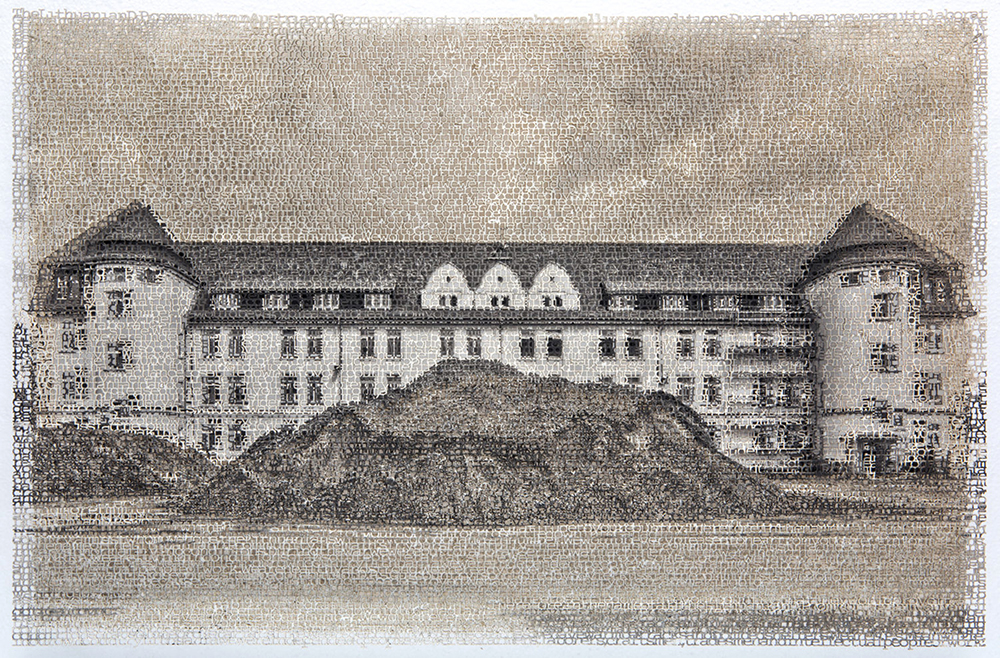

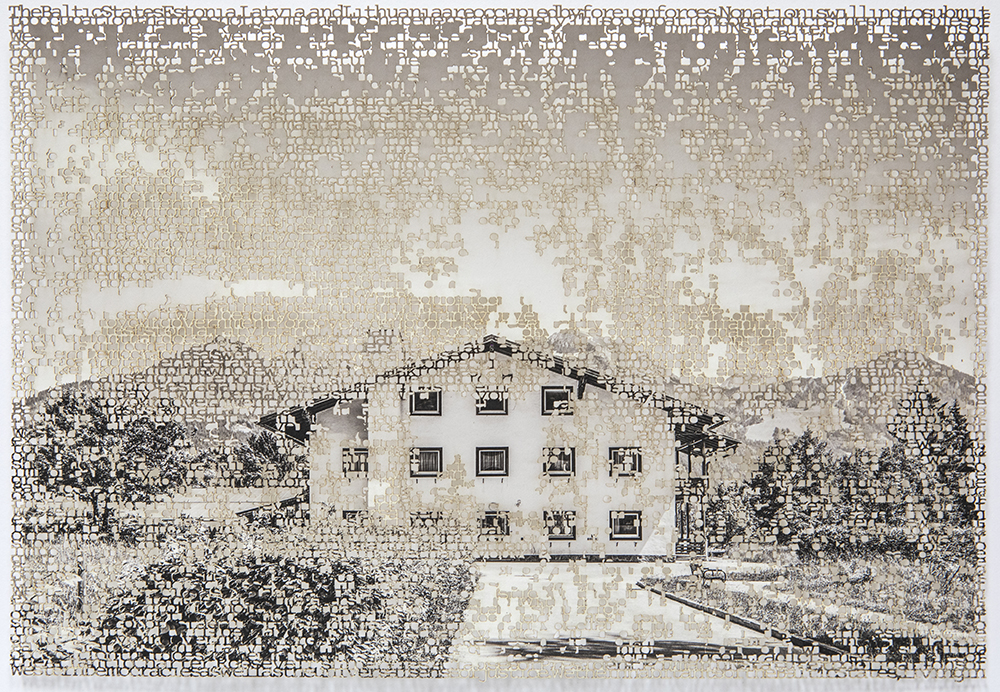

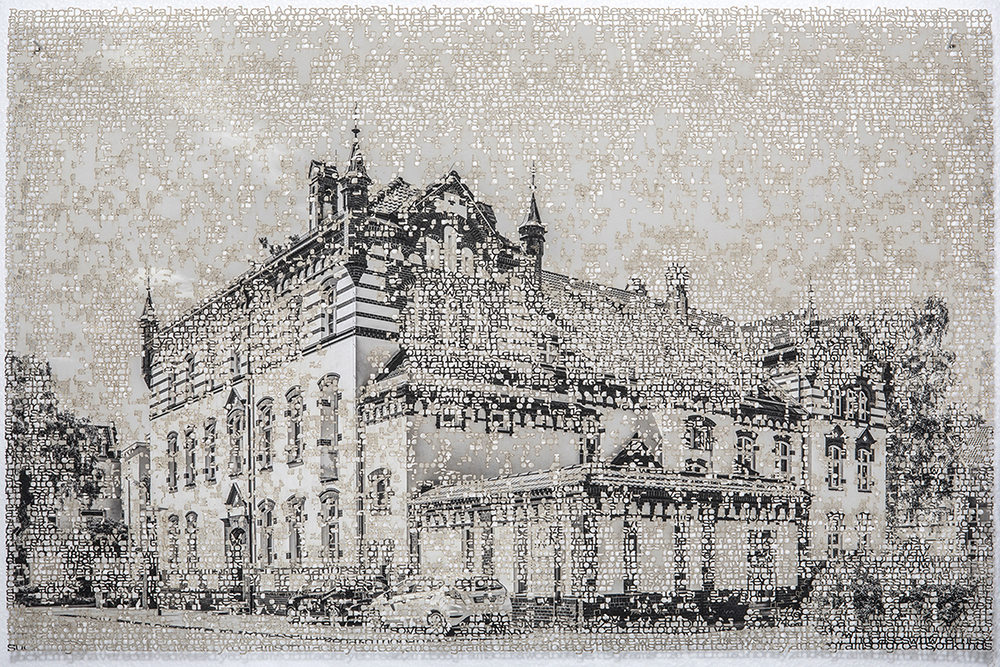

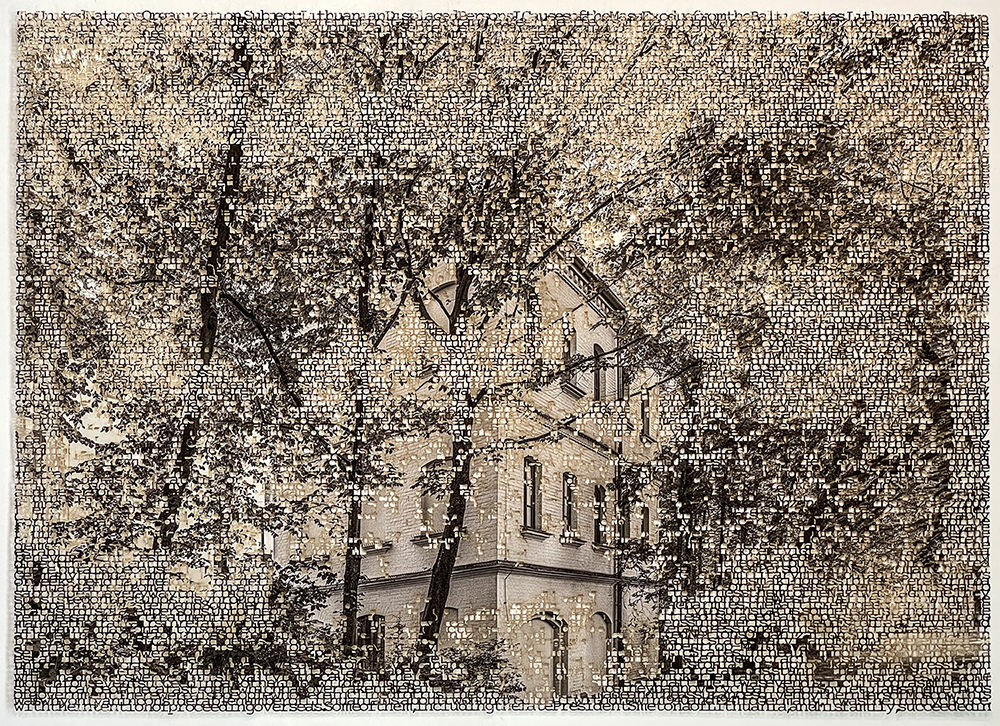

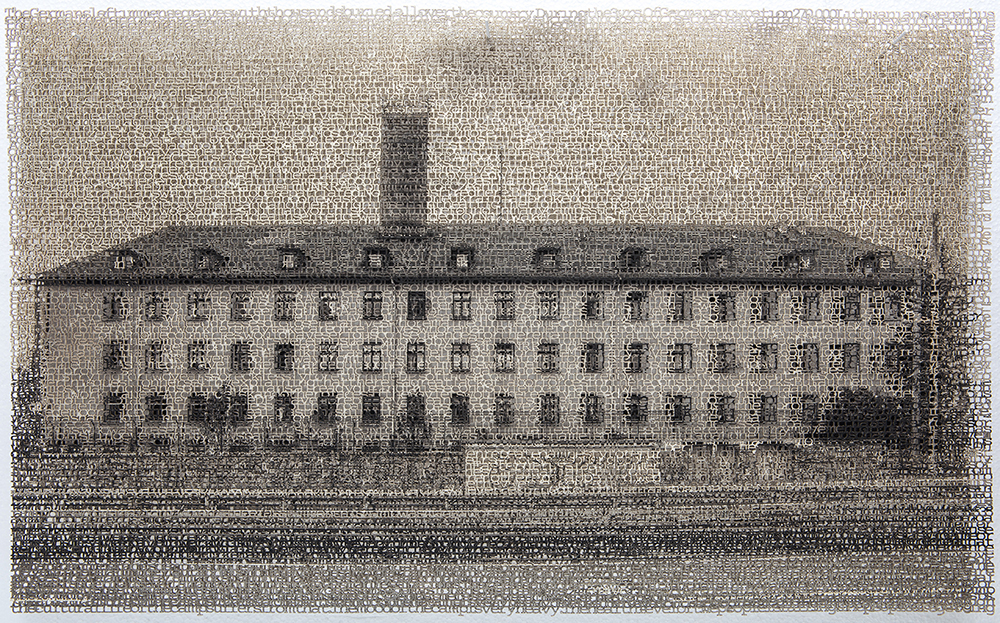

The work is a personal exploration of family histories after WWII, as her parents were confined to displaced-persons camps in Germany for almost a decade before they could make their way to the United States. The architecture reflects places where people were housed, which she deftly combines with archived copies of the plea letters the Baltic refugees sent to the governments of the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The work is then laser cut allowing for a powerful merging of place and memory. An interview with the artists follows.

Krista Svalbonas ( b.1977, USA ) holds a BFA in Photography and an MFA in Interdisciplinary studies. Her work has been exhibited in a number of exhibitions including at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, Spartanburg Art Museum in South Carolina, Howard Yezerski Gallery in Boston, Klompching Gallery and ISE Cultural Foundation in New York. Her work has been collected in a number of private collections, as well as the Cesis Art Museum in Latvia. Recent awards include a Baumanis Creative Projects Grant (2020), Rhonda Wilson Award (2017), Puffin Foundation Grant (2016) and a Bemis Fellowship (2015) among others. In 2022, Svalbonas will exhibit solo exhibitions of her Displacement series at Riga’s Photography museum in Latvia, The National Museum in Vilnius Lithuania and the Museum of Photography in Tallinn Estonia. She is an assistant professor of photography at St. Joseph’s University. She lives and works in Philadelphia. IG: @kristavalbonas

Displacement

Ideas of home and dislocation have always been compelling to me as the child of immigrant parents who arrived in the United States as refugees. Born in Latvia and Lithuania, my parents spent eight years after the end of World War II in displaced-person camps in Germany before they were allowed to emigrate to the United States. In this series, I set out to retrace and re-imagine that history.

My family’s displacement is part of a long history of uprooted peoples for whom the idea of “home” is undermined by political agendas beyond their control. My parents’ childhood homes were impersonal structures appropriated from other civilian and military uses to house thousands of postwar refugees. They had always described this housing as temporary, I never expected to see these buildings myself. But after intensive archival research, I was able to locate, visit, and photograph many of the actual buildings on the sites of former DP camps in Germany.

Today, the buildings give no hint of the tumultuous lives of the postwar refugees, stuck for years in limbo with no idea what the future held. To better understand and honor their struggles, I turned to archived copies of the plea letters the Baltic refugees sent to the governments of the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Page after page, they beg for food, bedding, and medical supplies, and attempt to explain the dire fate that would await them if they were repatriated to the Soviet Union.

I merge these painful accounts with the photographs through a process of burning, an echo of the traumas of war the refugees had endured. The works are a merge of text and image, where the words of the refugees form the complete image. Eventually made entirely of lace-like text, the images of buildings grow fragile, inseparable from the precarious lives they housed. Each of these layered pieces becomes a puzzle I am struggling to complete before the history is lost forever, a composite of my own experience and the fading memories of my parents and their generation. My goal is to give voice to this near forgotten history that also speaks to the impact of contemporary forced migrations.

Tell us about your growing up, the landscape of your childhood, and what brought you to photography.

From a very young age, I was always experimenting with some kind of artistic medium. My parents encouraged and supported my curiosity, allowing me to try my hand at sculpting, painting, drawing and photography. In high school I fell in love with photography and set up a mini darkroom in a closet under the stairs. I had, and still have, a thirst to learn and try new things. All through my education I was an alchemist, combining media and devising experiments. My mother was a huge influence. Although she never pursued a career in the arts, she is very artistic. I grew up with art all over the house. If it wasn’t my mother’s drawings, it was was my stepfather’s paintings and pottery. At one point my mother was part of a program sponsored by the Philadelphia Art Museum called ” Art Goes to School,” which introduced elementary students in Pennsylvania to various artists through show-and-tell poster prints. My mother had all sorts of prints of paintings and sculptures around the house. I remember falling in love with Chagall as a child through those posters.

Your work is so unique and compelling, share some background on the concept of the project–how did you find the locations and where did you access the plea letters?

I have a real penchant for research. Several of my projects have lead me to spend hours on end at various archives across the US. I’m not sure if my mother’s profession of a librarian has anything to do with this love of discovery. I certainly spent lots of my childhood roaming though library stacks. The research for this project was very intense, I traveled to 4 archives in the US and many small town archives in Germany. Most of the clues to the locations of these spaces I found in the UN archives in New York and in the Lithuanian archives in Chicago. These displaced person camps, were, at first, created by the allied military, so they all had military code numbers. Finding addresses was quite hard. If I found anything like a map or a fragment of an address I would then take that information to google earth and search the satellite imagery for two things; if the location was near a railroad station and if the building shapes matched any of the historical imagery I was able to locate. The plea letters are from the Lithuanian and Estonian archives here in the US. I found them randomly amongst the paperwork, as I was searching for addresses.

I would love to understand the process of making/burning the text…and how that concept came about.

At the time I began processing my first set of images of the camps in 2016, I’ve traveled to Germany 3 times to document, I was learning to use a laser cutter. Something just clicked, between the letters, my images and the process of burning through the laser. I thought, is there a way I could connect the words of the refugees with my images and burning seemed a very poetic execution of this. It took me about a year to figure out just how to do that. Lots and lots of failures, attempts and experiments. I create extremely detailed files for the laser to follow and I often have a negotiation with the laser to get the results I want. It’s much more unpredictable than one would imagine.

What’s next for you?

I’m currently working on a series, which also uses the laser cutter, combining my images of Baltic Soviet buildings with traditional Baltic textile patterns. This series explores the power of folk art and crafts as a form of defiance against the Soviet occupiers. It does this by focusing on how traditional textile designs provide a counterpoint to Soviet-era architecture and the memory of its totalitarian agenda. The juxtaposition of concrete structures with folk art designs also references the strength and determination of the women who created the weavings.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025