Text + Image: Alec Soth and Christopher Fausto Cabrera: The Parameters of Our Cage

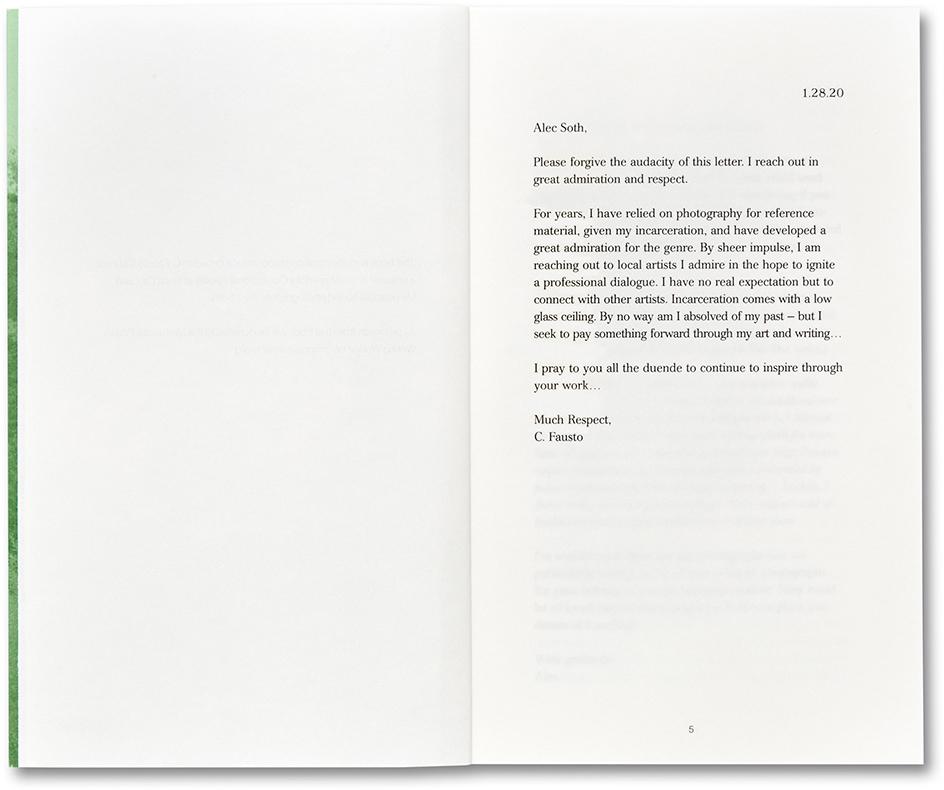

In January 2020, Christopher Fausto Cabrera sent a letter to photographer Alec Soth. A writer and inmate at the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Rush City, his goal was simple – to connect with a fellow artist. Heightened by the global pandemic and the murder of George Floyd in their own community, the resulting exchange is an insightful, poignant meditation on isolation and connection – both personal and social – as two artists from different racial and economic backgrounds explore the fraught nature of justice, privilege, and political divides in America.

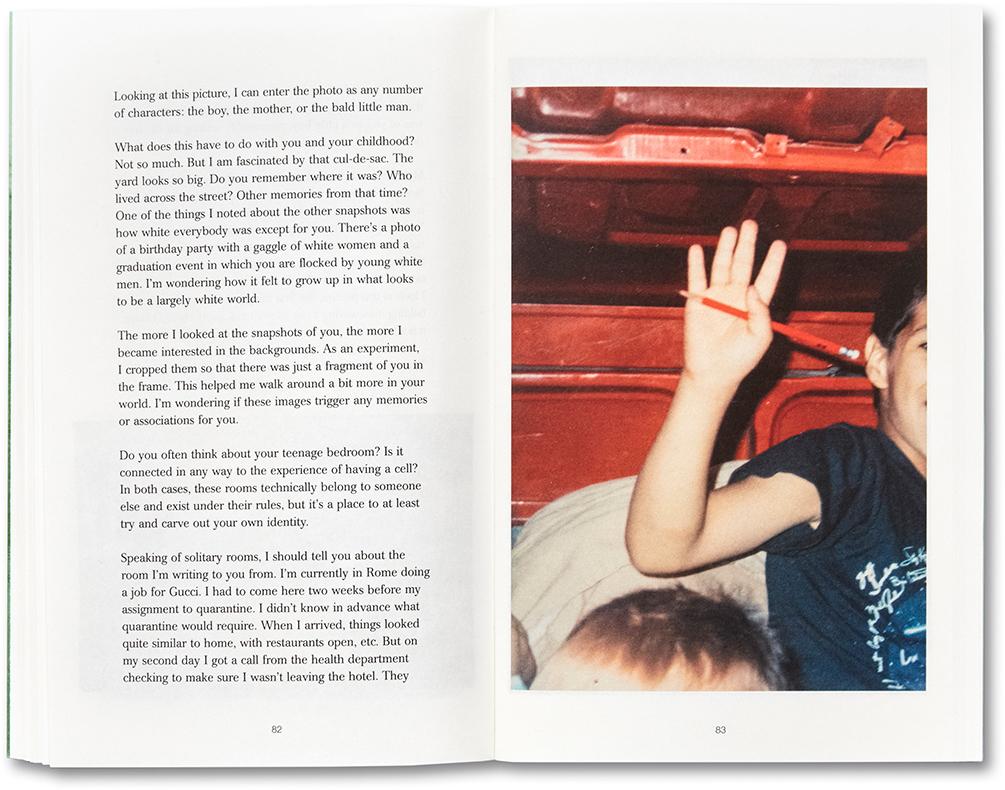

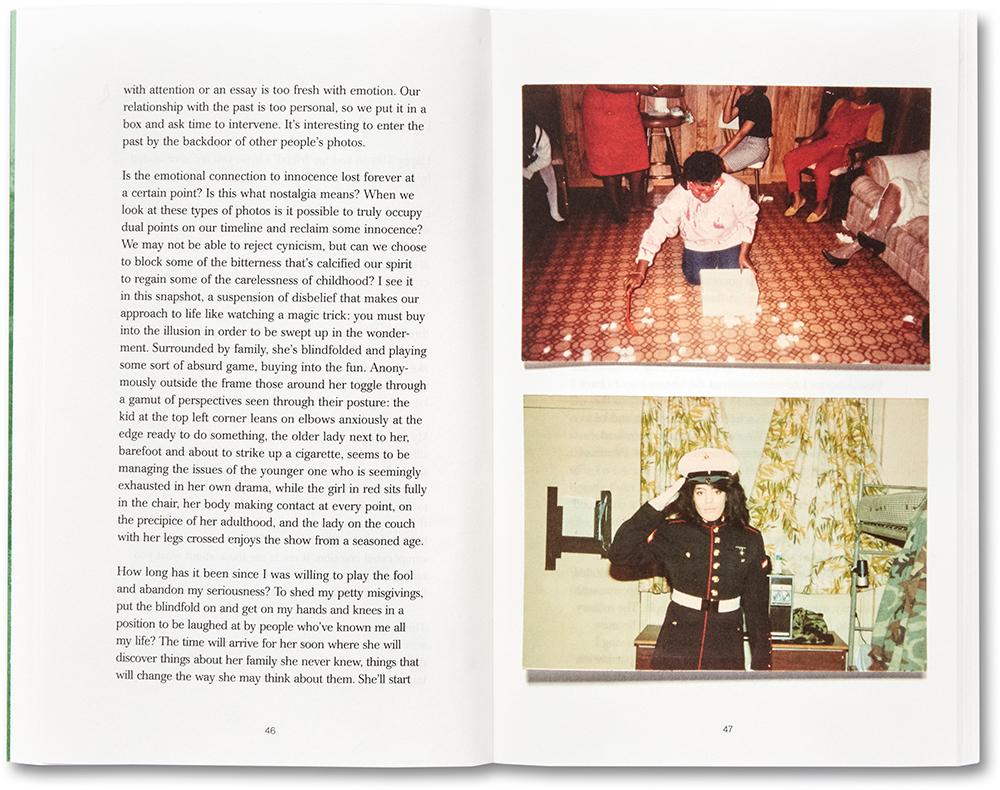

Over the following nine months they also discuss their creative influences, what it means to be an artist, and the power of creative expression. Their conversations often turn to the subject of photography, where photographs function as a form of remembrance, escapism, and catharsis. They reflect on snapshots (belonging to their families and others) and contemplate which eight photographs they would take with them to a desert island. In response, Cabrera shares an intimate family memory which Soth brings to life in two photographs. There are only a handful of other images reproduced in the book. Instead their conversation takes center stage, revealing the depth of a friendship made possible through genuine empathy and compassion. This record of their exchange, The Parameters of Our Cage, is one of the most impactful books I’ve ever read. I was fortunate enough to speak with photographer Alec Soth about the book, America’s continuing struggle towards racial justice, the importance of community, and his thoughts on image and text in photography.

In January 2020, Alec Soth received a letter from Chris Fausto Cabrera, an inmate of the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Rush City, in which he asked the photographer to engage in a dialogue. This sparked an expansive and insightful correspondence over the following nine months which, set against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, Black Lives Matter Movement and growing unrest, reaches to the heart of contemporary America. In amongst their exchanges of personal histories and shared influences – from Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man and André 3000, to Robert Frank’s The Americans and Rilke’s ‘Letters to a Young Poet’ – developed a searing investigation of the redemptive power of art and the imagination, justice and accountability, life inside America’s prisons, and the astonishing capacity of empathy and curiosity to bring two people together. – MACK Books

This interview took place on April 13th, 2021.

Kellye Eisworth: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me. I’m really looking forward to our conversation, but first I just want to acknowledge the death of Daunte Wright on Sunday and and ask how you’re doing?

Alec Soth: I mean, not good. It’s unbelievable. I’m afraid I don’t have anything eloquent to say except that it’s devastating on so many levels. It’s like there was this glimmer of hope, you know; spring was coming and it seemed like the Chauvin trial was going the right way…I mean, it was 70 degrees last week and now it’s snowing out.

KE: The fact that this happened at the same time Derek Chauvin is standing trial for the murder of George Floyd really brings the systemic nature of racism in this country into very sharp focus. His death sparked some intense, thoughtful conversations between you and Chris about the idea of justice that I found incredibly impactful and really important in this moment.

AS: I think it was a wake up call for so many people, and as someone who was fifty years old in 2020 it was remarkable the way it changed my thinking so dramatically. It was a real mind shift as so many of us started realizing we’re not doing this the right way and we need to change. But it’s not just this magic wand; it’s true that a lot of good things have happened but it’s going to be a long process of incremental change.

It’s interesting, because so much of our conversation takes place early on when there was this moment of optimism; the community was coming together and there was a feeling that change was possible. But now it’s a year later and it’s happening all over again. I wrote Chris yesterday and was like, tell me something…I’m at a loss here. None of it surprises him, he’s just like this is what it is; he’s very familiar with it and I guess I’m not as much. But it felt good to hear him say that we did something good through this book, because I just feel so helpless and unable to effect anything.

KE: Your conversations really demonstrate the potential to create empathic encounters with people whose life experiences are very different from our own simply by listening. In one of your letters you quoted Cornell West’s idea that “justice is what love looks like in public.” I think that’s a really beautiful lens through which to consider these kinds of conversations.

AS: That’s really great that you say that, because I’d forgotten it in this moment. When you’re so immersed in something…it’s like that feeling when you go out into nature after weeks behind a screen, it almost feels like you’re discovering it for the first time. So hearing that is like…oh right. Justice is what love looks like in public. I forgot because I don’t know what justice is. I don’t even have a clue.

KE: This point in the book made me think about the idea of the parameters of our cage and how we respond to those limitations in a different way. The New York Times asked you to photograph the protests in Minneapolis, but you sent them a list of black photographers whose perspectives you felt were more important than your own instead. I think confronting and acknowledging the ways in which the privilege we may hold- those limitations in our understanding of the world- also defines us in a big way.

AS: Yeah, right. It’s funny, because had we had this conversation a week ago I would have taken it very differently, I’m just at a loss with all of that at the moment. But yes, it’s like, empathy is the key. We have to keep learning the lessons over and over again. It’s like what I was saying about nature- you forget that it’s there. You forget that everyone is not just a group, that other people are human beings with different perspectives. But even though we may be different, there’s something shared. That’s so easy to forget.

It’s like that idea of living in a bubble. You know, I don’t think that I knew I was in a bubble when I was young, and there are lots of reasons for that; that’s just the nature of privilege itself. Sometimes you’re in a bubble because you live in a community that’s all one color and you’re not going to other places. And as a photographer, I’ve driven around the country meeting all sorts of people who I may have disagreed with on a lot of stuff, but they were still amazing human beings. Over these last four years I’ve felt like I must have been delusional for thinking that, but I think that’s also because I’m only seeing them through the way they’re portrayed on television instead of really talking to people. Everyone becomes an abstraction, which isn’t healthy. That’s the great thing about this interaction with Chris, because I have all these preconceptions about prison- we all do, you know, it’s such a media phenomenon- but having a human conversation changes things and makes it more complex, and that’s so good.

KE: How has collaborating with Chris on this project changed your perspective of your role in centering these kinds of dialogues and creating space for others that haven’t necessarily had the same opportunities to make their voices heard?

AS: It’s a work in progress. I was conflicted about publishing it, even; I was conflicted about the appearance of exploiting something or making myself look good or any of those issues. And I think we all confront this all the time, where it’s like, do I post something on social media because it makes me look good or am I trying to do good? It’s very complicated. So I think it’s definitely important to get the message of elevating other people’s voices but being thoughtful about your motivations and how you’re doing it and so forth. Where it becomes complicated for me is where it overlaps with my own work, because then I’m like tying it into my own ego fulfillment. That’s why I don’t want this to come off as my art. It’s very meaningful, but I think of it as separate from the rest of my creative practice and not as a project exactly.

KE: Chris originally reached out to you because he wanted to connect with other artists. I think a lot of us can relate to this kind of inherent need for community within our creative practice. I was wondering if you could kind of talk about that, in your own practice and in general?

AS: I thought I was attracted to photography because of its solitary nature, but you quickly realize you need community. First of all because the idea is to share your work with other people. When I started doing photography here in Minnesota after I graduated there was a local photo community with elders and a gallery space everyone would go to. All of that is gone now and a lot of it shifted online. But in a funny way, that suited me because of my personality. I would go to those local events, but I was too shy to talk to the legendary local photographer or whatever anyway. That world of blogs or whatever ended up being a very good community for me and I’ve actually made a lot of connections through that. We all need community and we find it in different ways. I think we’re in the middle of another big change in photography; it’s not easy, but it’s exciting and I think communities will be formed and shaped in new ways and good things will come out of it.

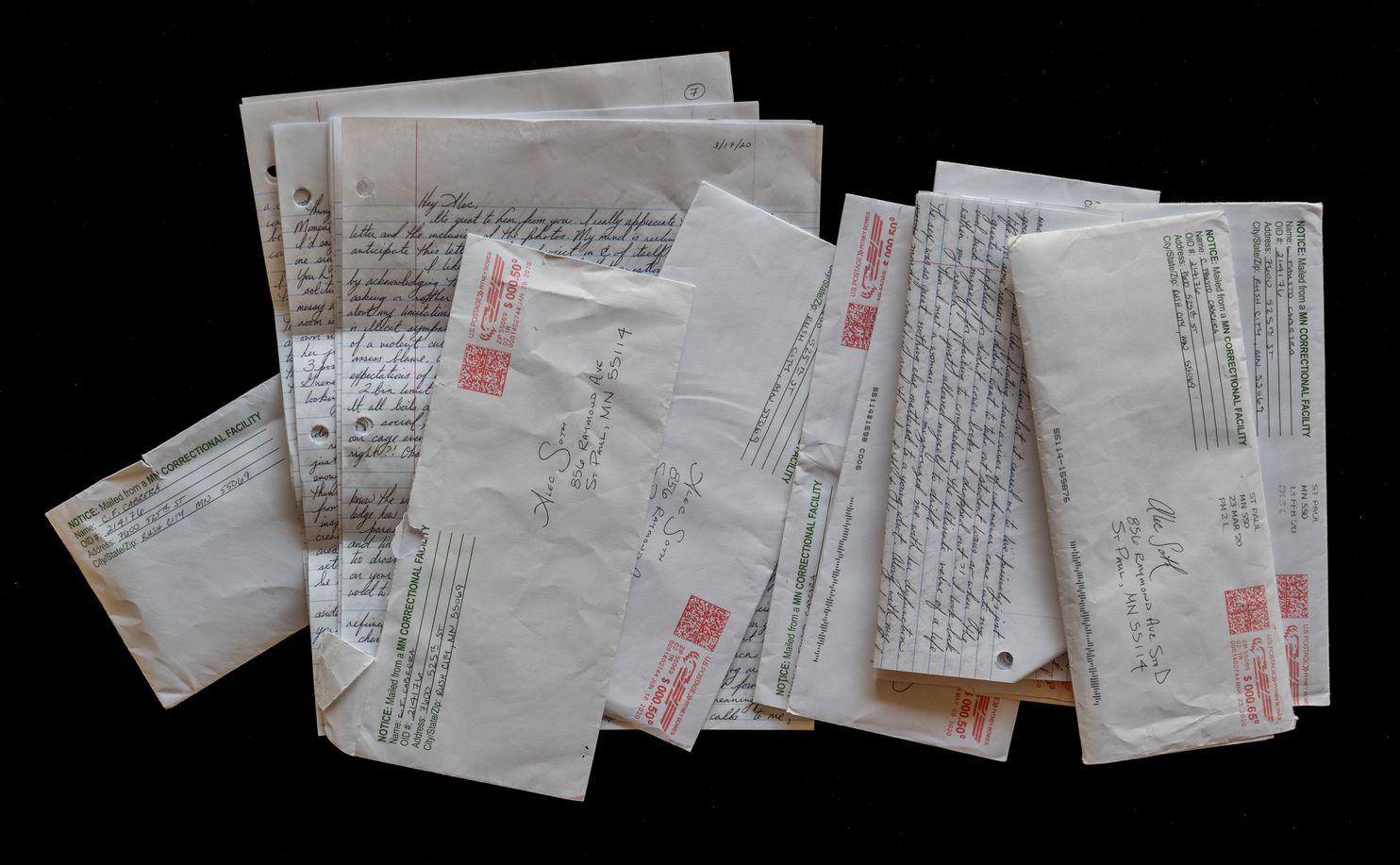

But even though they are going to be things like NFTs and a whole world virtual content, I do think there’s going to be an equal push to do physical stuff and be in the world. People still value and crave the physical. It’s interesting to think about how the nature of media has changed in relation to Parameters and how it effected my relationship with Chris because it started in this pre-digital form of the letter. Now we communicate through email or on the phone every week or two, but there was something so beautiful about the letters, not only because it’s a physical object but also embedded within it is distance, of course, and the waiting. I think the fact that the book is written in the form of the letter also makes it more accessible because it feels less like preaching than just talking.

KE: I found it really beautiful that the photographs you made in response to your conversations with Chris are included as postcards you could use to start a dialogue with someone else. What was the impetus behind that decision?

AS: Originally, I sent the photographs to Chris as a large print cut up into small pieces (in order for it to fit into the proper envelope) that he could assemble it on the floor or on the wall of his cell so that he could really see the landscape and feel it big and I wanted to include them that way in the book as well. Unfortunately, there’s a limit to the number of sheets you can send per envelope, so he never got it. At the same time, the publisher and I realized that it wouldn’t work for the book either because we wanted it to be inexpensive and that approach raised the cost too much. Ultimately, I decided to make them postcards because I liked the idea that my pictures somehow weren’t part of the book and theoretically I could send him that postcard.

KE: This feature is part of our series on image and text. Normally we think of that genre of work being a relatively balanced mix of both elements, but there are only a handful of photographs in this book. Do you think it fits within the idea of image and text?

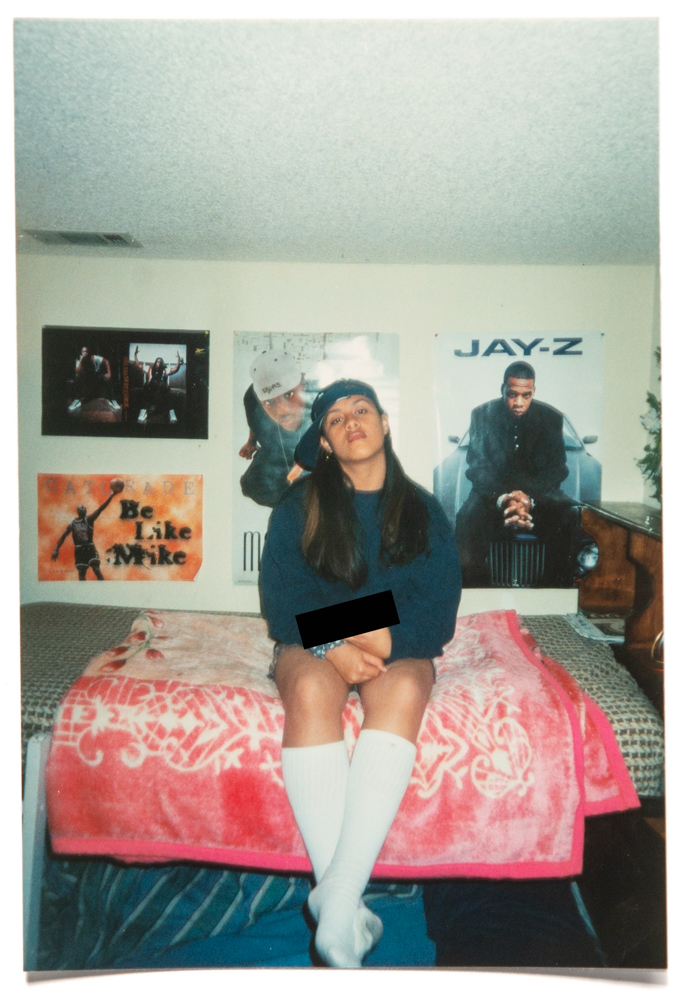

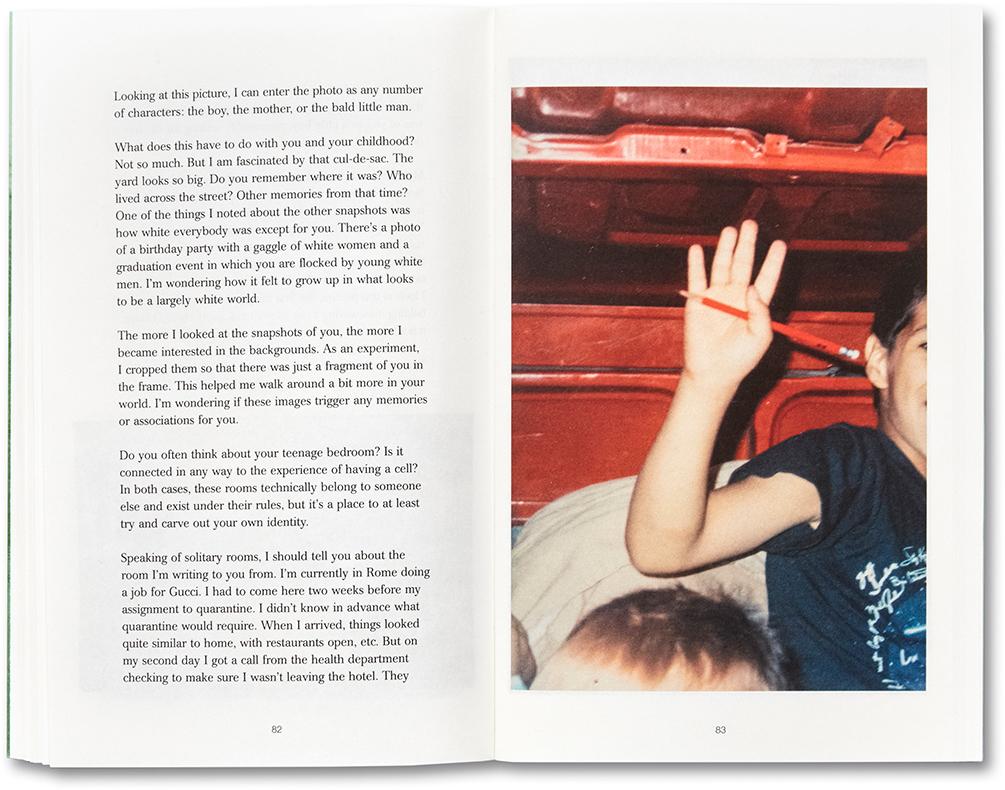

AS: It’s funny because I’ve played a lot with this issue of image and text (particularly through Little Brown Mushroom) and I have this theory that, generally, the more words there are the less interested I am in formal pictures. For instance, I just did a book with the writer Brad Zellar which was mainly text and my photos were disposable camera pictures and I thought they balanced each other out- like, if I have highly detailed 8×10 pictures I kind of want little tiny text in the back of the book or for the scales to go the other way. I don’t think of Parameters as an art book per se, but that’s why at a certain point I decided I wanted it really to be a book of text that has just a few images. Chris and I talked about some famous photographs but I didn’t reproduce them. I also sent him many of my photographs but I edited all of that out because I didn’t want it to be like my book of photographs. I think the informality of the vernacular pictures works for this because it doesn’t stop the flow of the text.

KE: You’ve done several YouTube videos about image and text. What is it about that kind of work you’re drawn to?

AS: I feel like I’m in a perpetual wrestling match with image and text. On the one hand, a primary goal of mine is to share the creative process itself. Storytelling is often the most powerful way to communicate this process. On the other hand, a photograph is as much about what’s left out of the frame as what’s in it. By limiting itself to a wordless sliver of time, a photograph allows the viewer to write her own story. What to do? I look at other people’s books for help.

C. Fausto Cabrera is a multi-genre writer and visual artist incarcerated since 2003. He is a member of the Board of The Minnesota Model of Youth Diversion Project, co-founder of The Stillwater Writers Collective, partnered with Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop (MPWW) and dedicated Inmate Advocate. His work has appeared in From the Inside Out: Letters to Young Men and Other Writings (2009), The Missouri Review’s Literature on Lockdown (2014), Poetry Behind the Walls (2017), The Colorado Review (Fall/Winter 2018), American Literary Review (2019), The Washington Post Magazine (2019) and on WeAreAllCriminals.org

Alec Soth is a photographer born and based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His photographs have been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, is included in major institutional and private collections across the world, and has been published in numerous monographs and catalogues.

Follow Alec on Instagram: @littlebrownmushroom

The Parameters of Our Cage is part of the Mack Books DISCOURSE series of small books in which a cultural theorist, curator, or artist explores a theme, an artwork, or an idea in an extended illustrated text.

All proceeds from this book will be donated to the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Hillerbrand+Magsamen: nothing is precious, everything is gameOctober 12th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025

-

Christa Blackwood: My History of MenJuly 6th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-KilroyMarch 27th, 2025

-

Dodeca Meters: Arielle Rebek, Kareem Michael Worrell, and Lindsay BuchmanFebruary 7th, 2025