Claudia Ruiz Gustafson: La Ciudad en las Nubes

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series La Ciudad en las Nubes by Claudia Ruiz Gustafson.

Claudia Ruiz Gustafson is a Peruvian visual artist and curator based in Massachusetts whose practice engages photography, assemblage, poetry and artist book making. Her work is mainly autobiographical and self-reflective; her cross-cultural experience and Peruvian heritage deeply inform her art making. Claudia’s latest projects explore the stories of her Peruvian ancestors and aspects of her immigrant and liminal experiences. In her latest ongoing body of work Mi País Imaginado, she is in dialogue with historical extractivist events, reframing and recontextualizing those narratives within a contemporary gaze while exposing the mechanisms of the imperialist machine that made them possible.

Claudia has exhibited in museums and galleries across the US and abroad at venues including Danforth Art Museum, Griffin Museum of Photography, Newport Art Museum, Photographic Resource Center, Agora Gallery, Millepiani Gallery and Galleria Valid Foto. She is a 2021 Mass Cultural Artist Fellow, 2020 Critical Mass 200 Finalist and 2020 Photo LA Top 20 Finalist.

Claudia has received grants and awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Cambridge Art Association, L.A. Photo Curator: Global Photography Awards, PX3 de la Photographie Paris, The Gala Awards, among others and her work has been published in Fraction Media, Black & White Magazine, F-Stop Magazine, Float Photo Magazine, Aspect Initiative and Lenscratch.

Currently she is curator and participating artist of the traveling exhibition Crossing Cultures: Family, Memory and Displacement, a multi-media project made up of artwork created by multi-cultural artists reflecting on identity and diaspora.

She holds a BA in Communications (Comunicación para el Desarrollo) from Universidad de Lima, and a Professional Photography Certificate from Kodak Interamericana de Perú.

La Ciudad en las Nubes

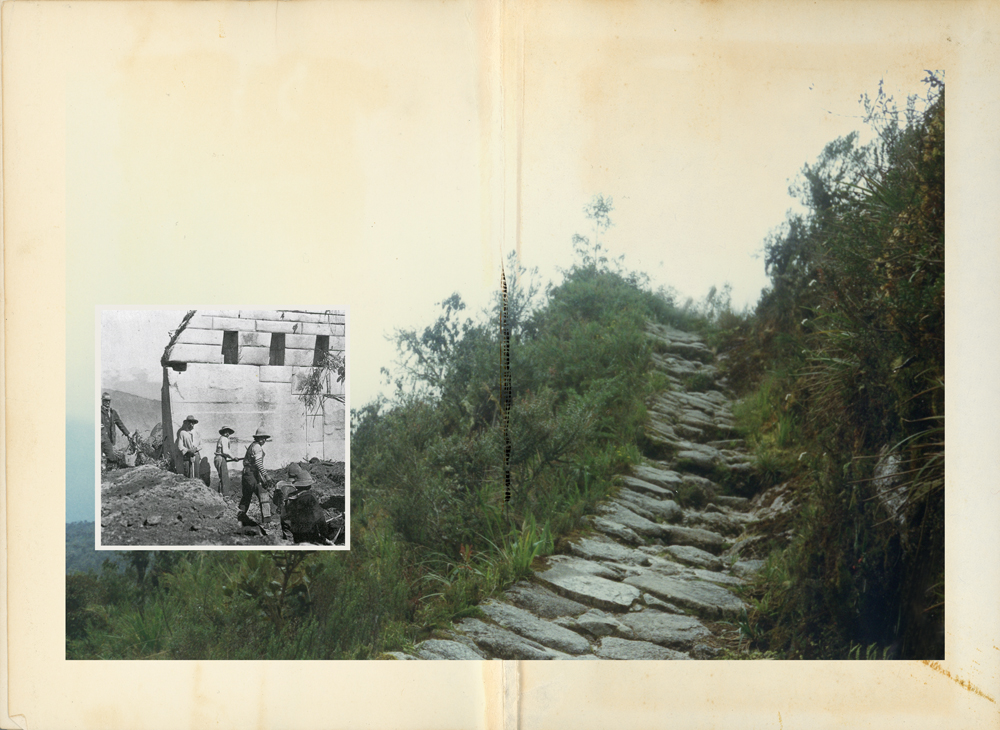

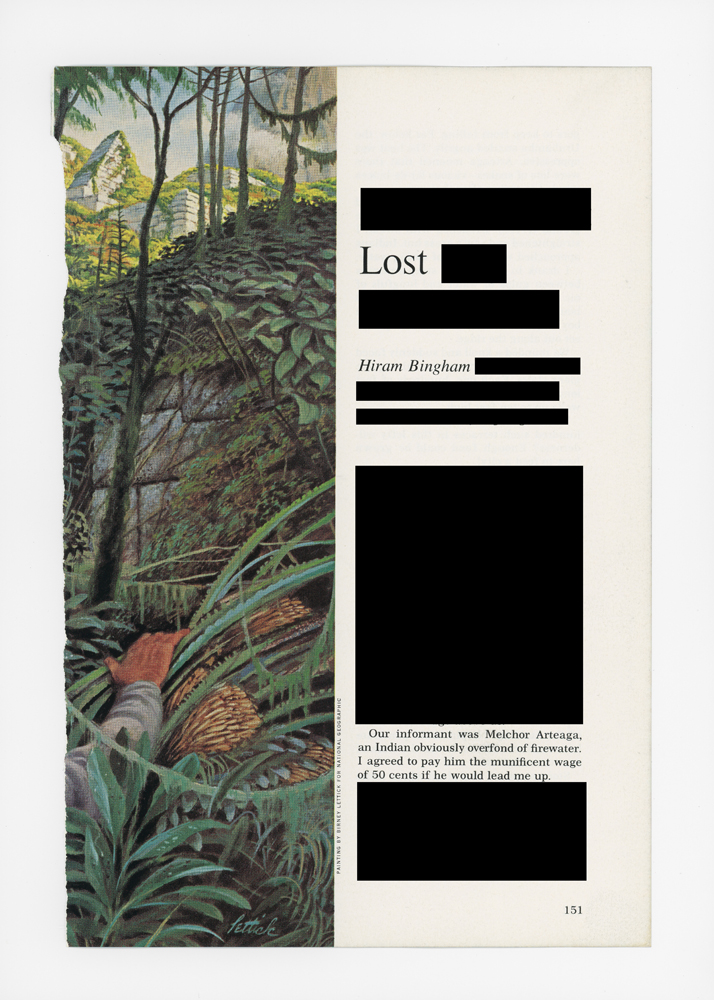

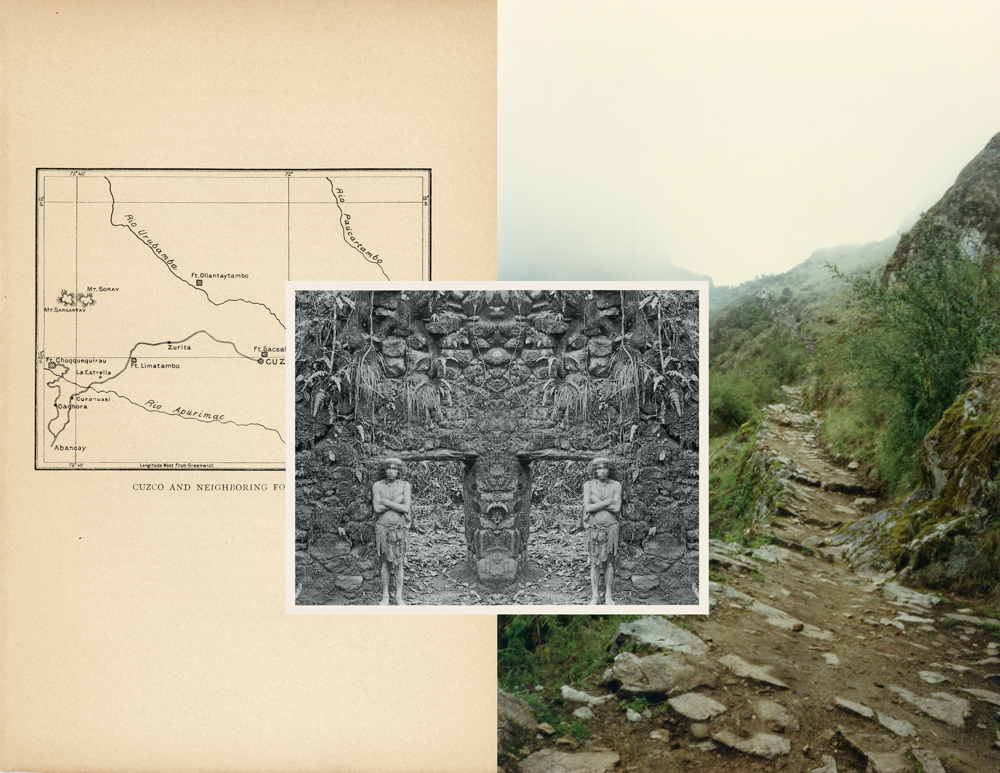

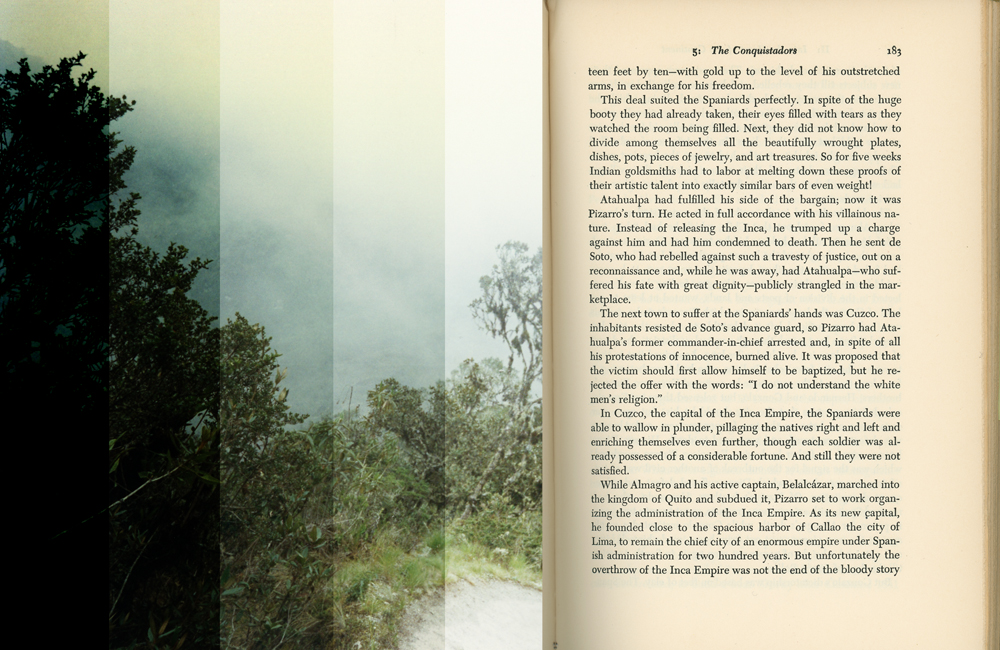

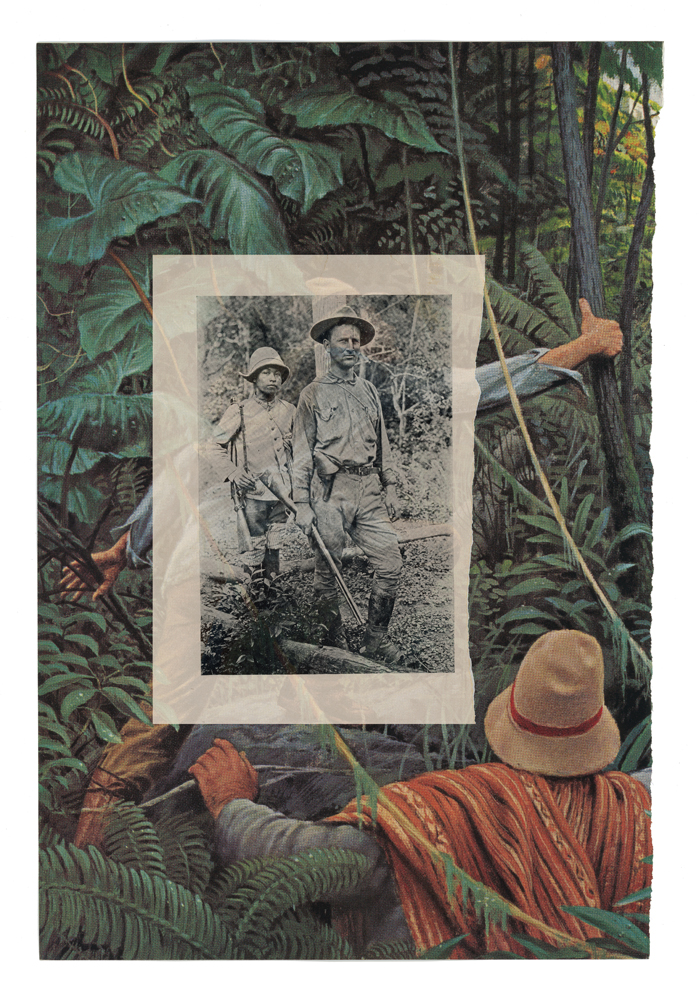

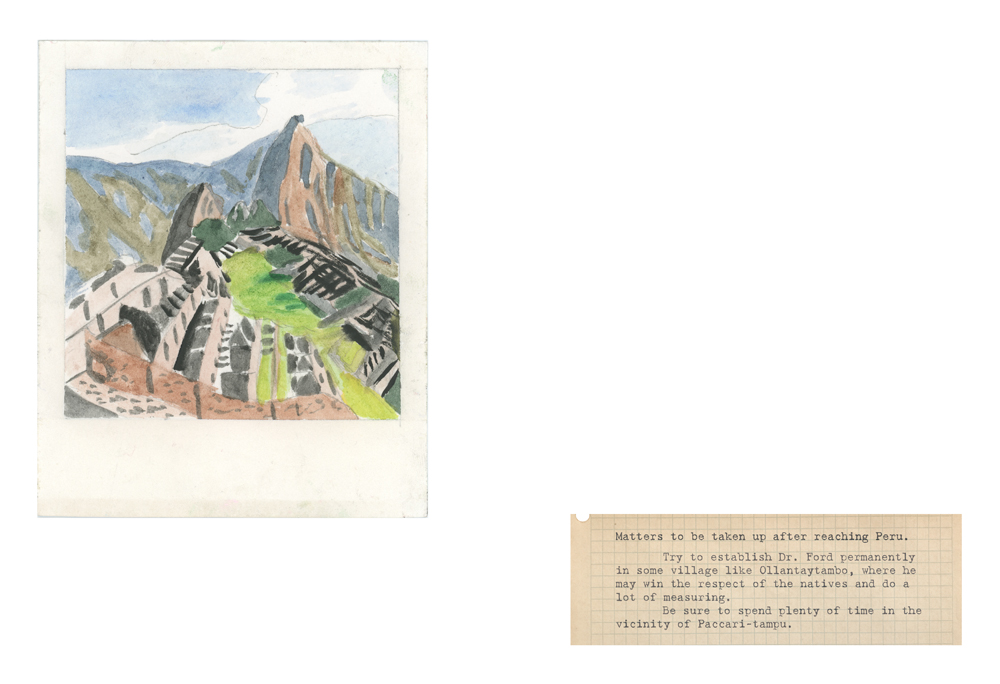

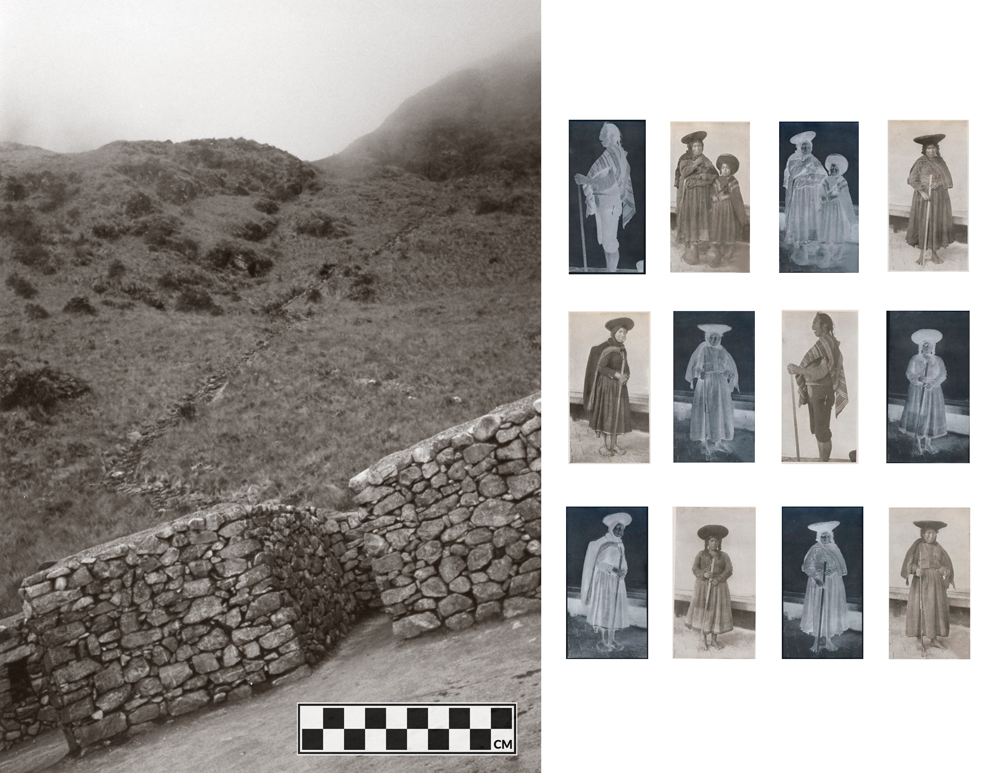

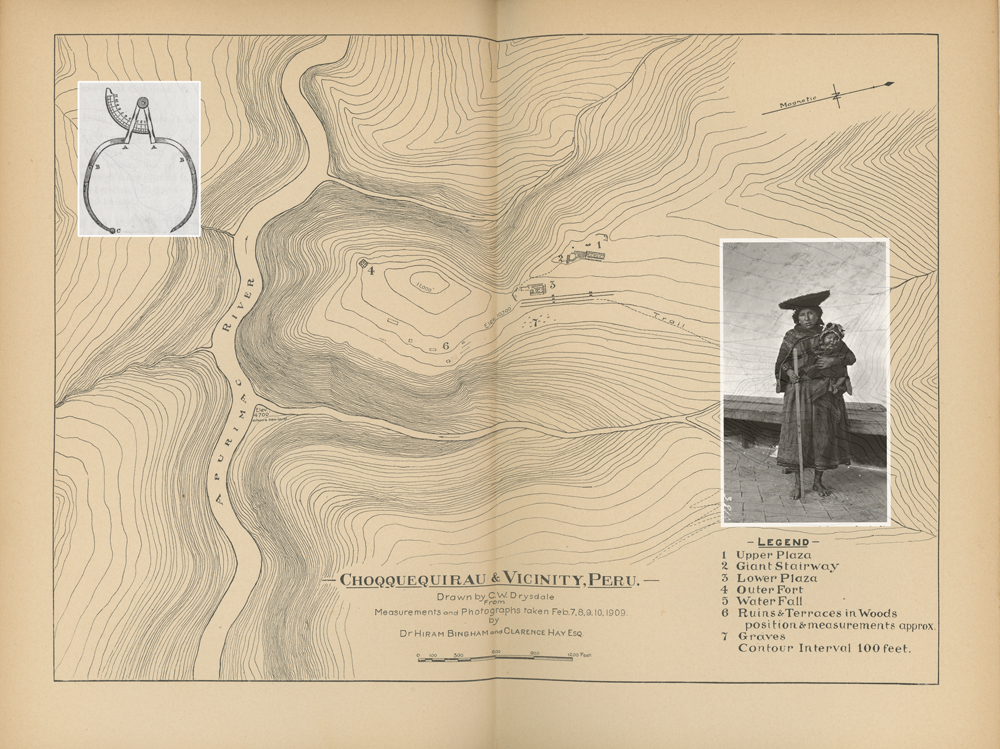

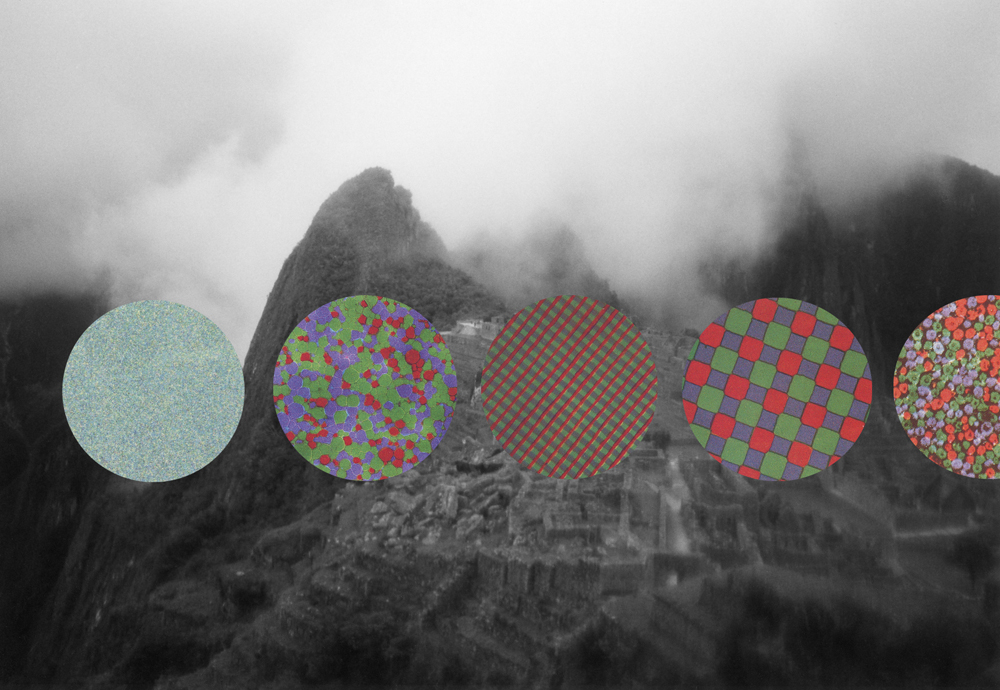

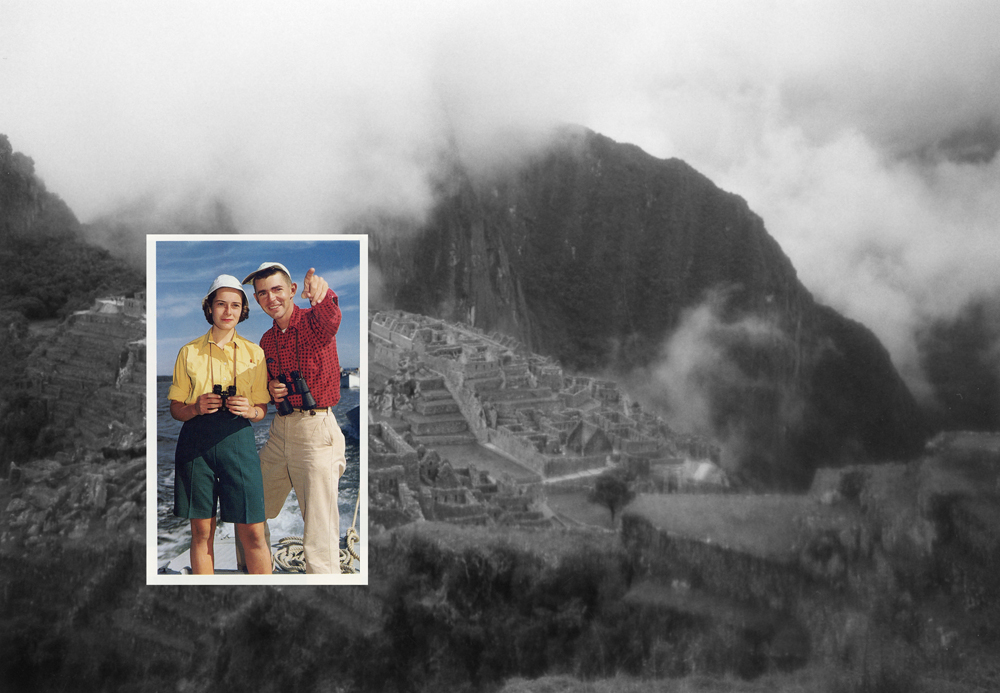

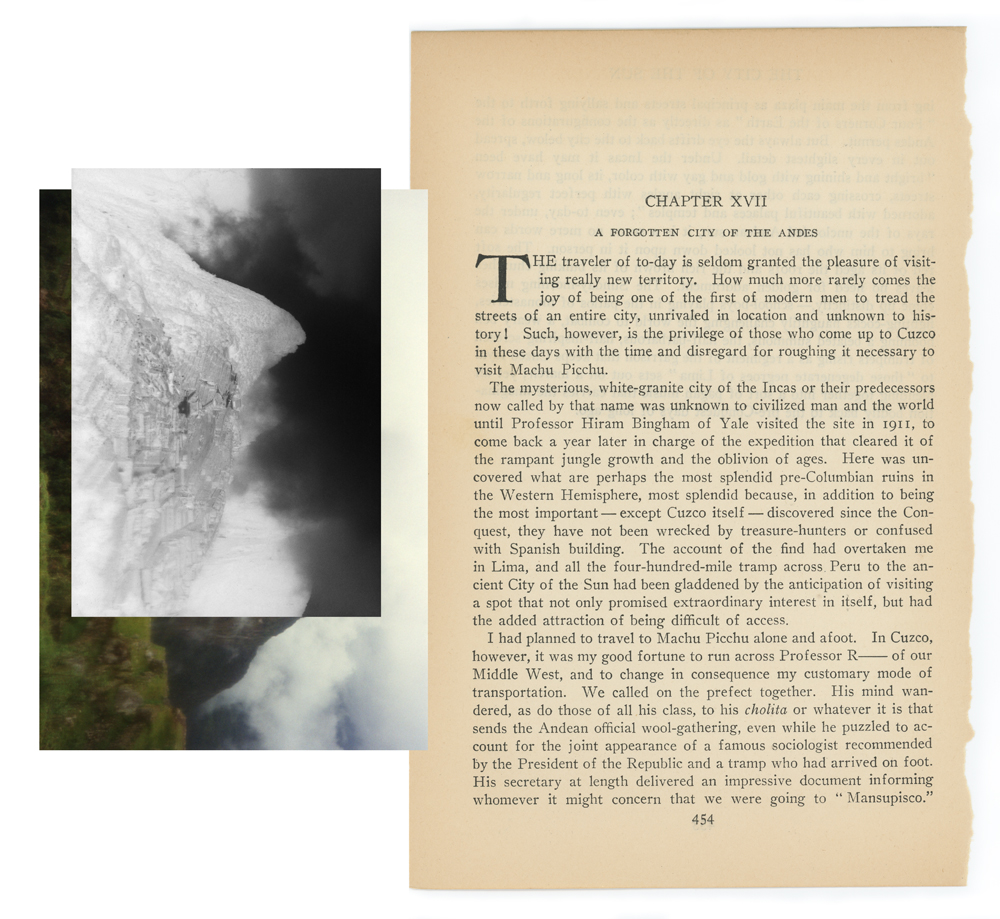

In this project, I reflect upon the impact of Hiram Bingham’s expeditions to Perú. A Yale University historian. Bingham was one of many western white men to lead colonial explorations between 1911 and 1915 using the advancement of science as an excuse to plunder ancient indigenous cultures. Using my photos made during a trip to the Caminos del Inca (Inca Trails) in 1998, alongside archival documents, this work retells the official version of the “discovery” of Machu Picchu.

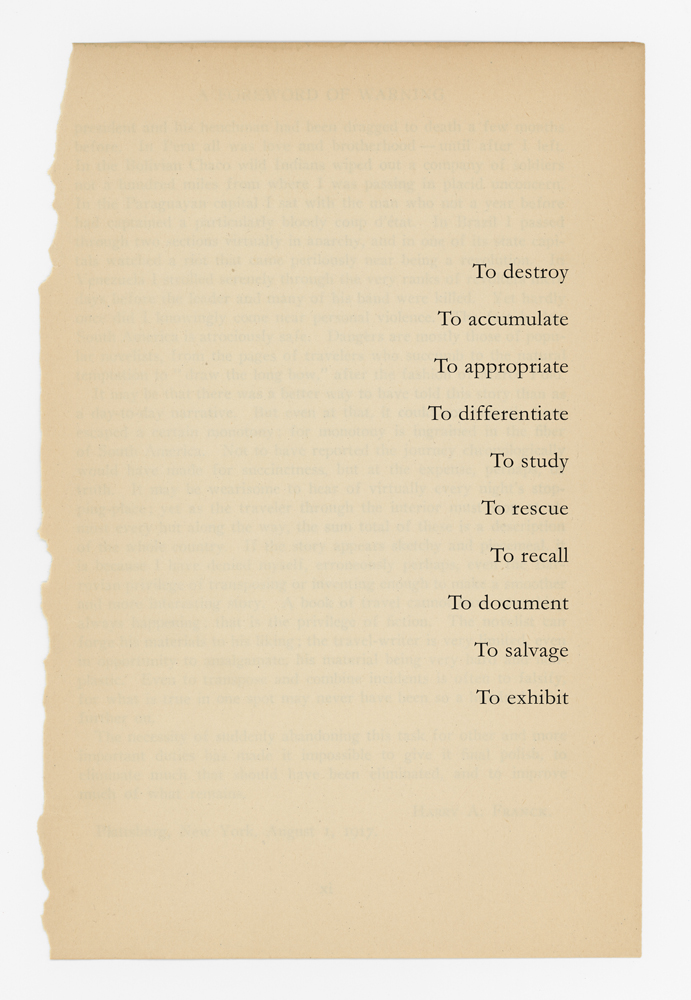

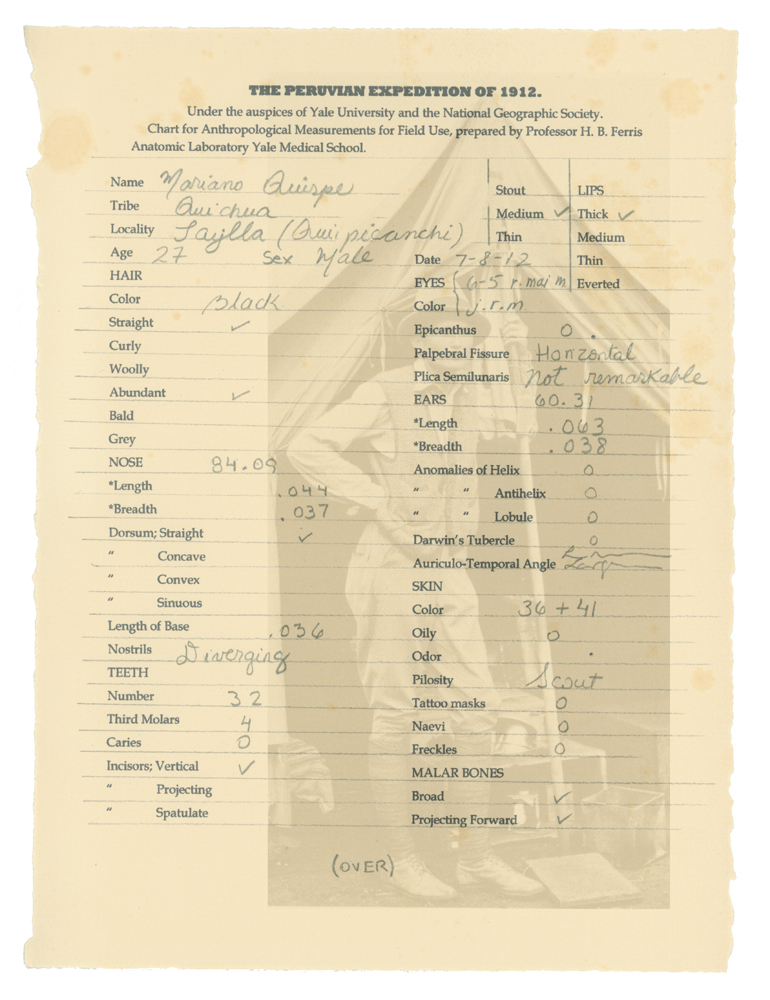

Financed by the National Geographic Society and Yale, Bingham is credited with the “discovery” of Machu Picchu. He was not an archeologist and there were no archeologists accompanying him. Bingham and his team dissected the Quechua community and looted sacred graves under the guise of archeological research. They ignored the Quechuas except as guides to find the ruins, to do the excavation work, and as subjects to study for anthropometry. None of the expeditions considered the local people who for centuries lived nearby and who were familiar with the nearby ruins. In fact, Machu Picchu was discovered years earlier by a local farmer named Agustín Lizárraga Ruiz.

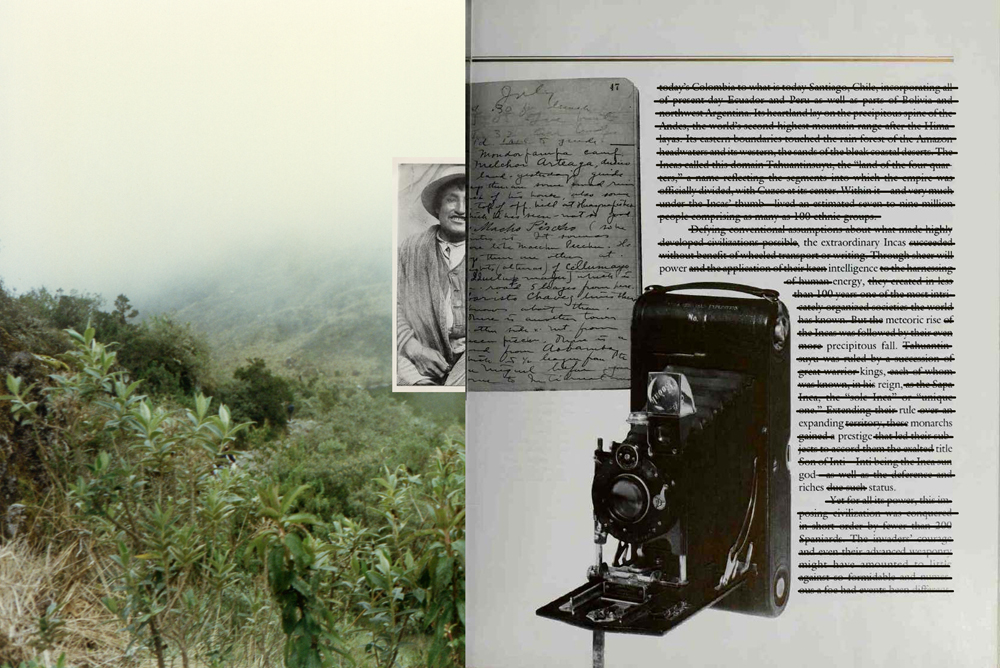

Over the course of his expeditions, Bingham took 12,000 photographs with cameras donated by Kodak. For Yale, he collected hundreds of human remains and artifacts. These photographs were published in Harper’s Magazine and National Geographic who held the exclusive rights to them, and Machu Picchu went on to become a discovery of science and the property of Yale University as its custodian. In recent years, Peruvians have been awakened to our own heritage and have demanded the return of certain artifacts. In fact, in 2012 Yale University returned a third batch of several relics to their rightful owners, the people of Perú.

Daniel George: Besides being from Peru yourself, what prompted your interest in more closely examining the impacts these expeditions had on the country?

Claudia Ruiz Gustafson: Last summer I read the book by the professor and academic Ariella Aisha Azoulay Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism which was very influential for me. For a long time, I have been thinking about the effects of colonialism in my country, how until today our natural resources, raw materials, people and stories continue to be exploited by imperial actors. I have been deeply researching the situation in Peru through the years because I was looking to create a project around the bicentennial of our independence with Spain, which is precisely this year, 2021. Are we really free as our anthem says?

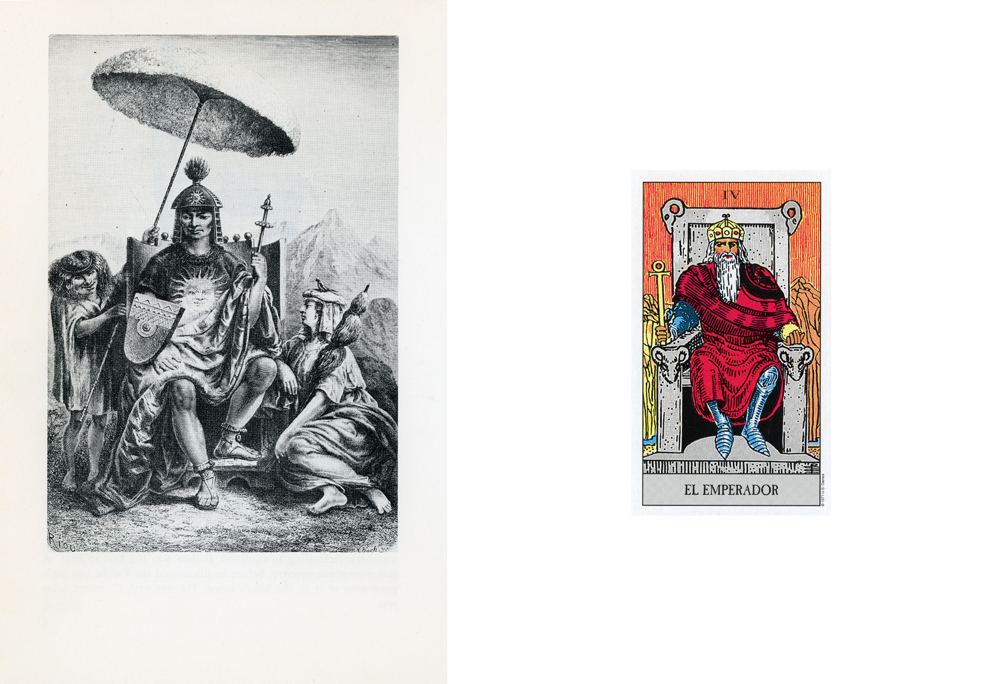

The pandemic prevented me from traveling to Peru so I visited antique bookstores in Boston, and I was struck by finding so many books about expeditions to Peru written by North American and European men. When I started this project, La Ciudad en las Nubes, it included various expeditions, but as it progressed, I focused on the Machu Picchu expeditions because this place has become an icon of Peru and is well known worldwide. In this project I use these expeditions as the placeholder of many others where privileged white men traveled to my country to open up cultures, loot sacred places, being helped by local people and often by the president or local mayors at the time.

These men wrote books describing Peru from their points of view, stereotyping its people, and othering them. In many of these books, the authors mention Hiram Bingham, the explorer who was credited as the discoverer of Machu Picchu as an inspiration. Bingham himself was inspired by a book by William Prescott, a Bostonian and Harvard graduate who wrote a book on the history of Peru without ever stepping on Peruvian soil, that really caught my attention.

Another book I came across was by cultural anthropologist Amy Cox Hall, the recently published Framing a Lost City. Cox Hall had access to the Bingham archive in which many documents and letters have come to light, Bingham did not act alone; he had an important network of influential people who helped him and financed him, and he became the Peruvian expert in the United States consulted by investors interested in Peru. The history is very rich, but I focus on the myth of the discoverer, a false myth that has been perpetuated and one I think needs to be corrected.

Daniel George: Además de ser de Perú, ¿qué motivó tu interés en examinar más de cerca los impactos que estas expediciones tuvieron en el país?

Claudia Ruiz Gustafson: El verano pasado leí el libro de la profesora y escolástica Ariella Aisha Azoulay Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism el cual fue muy influenciador para mí. Por mucho tiempo he estado pensando en los efectos del colonialismo en mi país, la manera como hasta hoy nuestros recursos naturales, materias primas, personas e historias siguen siendo explotados por actores imperiales. Desde hace mucho vengo leyendo e investigando acerca de la problemática del Perú porque estaba buscando crear un proyecto en torno al bicentenario de nuestra independencia con España que es justamente este año, 2021. ¿Realmente somos libres como dice nuestro himno?

La pandemia evitó que pudiera viajar a Perú así que me recorrí librerías de anticuarios en Boston, y me llamóla atención encontrar tantos libros acerca de expediciones a Perú escritos por hombres norteamericanos y europeos. Cuando empecé este proyecto, éste incluía diversas expediciones, pero a medida que avanzaba, me centré en las expediciones de Machu Picchu porque este lugar se ha convertido en un ícono del Perú y es conocido mundialmente. En este proyecto uso estas expediciones como el ejemplo de muchísimas otras donde hombres blancos con mucho privilegio viajaron a mi país para abrir culturas, saquear lugares sagrados, siendo ayudados por gente local y muchas veces por el presidente o los alcaldes de turno.

Estos hombres escribieron libros describiendo al Perú desde sus puntos de vista, estereotipando a sus pobladores y otreándolos. En muchos de estos libros, los autores mencionan como inspiración a Hiram Bingham, el explorador al que se le atribuye el mérito de ser el descubridor de Machu Picchu. El mismo Bingham se inspiró en un libro de William Prescott, un Bostoniano egresado de Harvard que escribió un libro de historia del Perú sin nunca pisar suelos peruanos, eso me llamó muchísimo la atención.

Otro libro que llegó a mis manos fue el de la antropóloga cultural Amy Cox Hall, Framing a Lost City, reciente publicado. Cox Hall tuvo acceso al archivo de Bingham en el cual muchos documentos y cartas han salido a la luz, Bingham no actuó solo, tuvo una red importante de personas influyentes que lo ayudaron y lo financiaron, él se convirtió en el experto peruano en los EEUU donde los inversionistas interesados en Perú lo consultaron. La historia es muy rica, pero yo me centro en el mito del descubridor, un falso mito que se ha perpetuado y que me parece se tiene que corregir.

DG: Could you talk a bit about your process, and your decision to include both your photographs and archival documents?

CRG: Once I decided to focus on Machu Picchu, the first thing I did was scan all my analog photos from when I traveled the Inca Trail in 1998, which was a very significant experience for me as a Peruvian, it was a kind of pilgrimage. Those slightly faded photos of the area of the Sacred Valley of the Incas, reflect my own spiritual path to Machu Picchu, and when combined with Bingham documents and other archival documents that I could find, tell a different story. Those people did not feel a love for my country, or an interest in its people; their motivations were the same as the conquistadores: the search for adventure, wealth, prestige and fame, which added to their lack of understanding of the language or the very different cultures that exist in my country with their particular cosmovision.

Each piece deals with some aspect of the expedition, emphasizing its relationship with the local community as well as the process that led Machu Picchu to become one of the most exotic destinations in the world.

In this project I also include the ethnographic photos that the physician of the Bingham expedition took of the Cuzqueño people. All of them were taken by force to be measured and analyzed by strangers. I can only imagine how humiliating it was, and how little those expeditions meant to them where they were considered to be nothing but manual laborers. This is a work still in progress.

DG: ¿Podrías hablar un poco sobre tu proceso y tu decisión de incluir tanto tus fotografías como tus documentos de archivo?

CRG: Una vez que decidí concentrarme en Machu Picchu, lo primero que hice fue escanear todas mis fotos análogas de cuando hice los Caminos del Inca en 1998, una experiencia muy significativa para mí como peruana la cual fue una suerte de peregrinación. Esas fotos un poco descoloridas de la zona del Valle Sagrado de los Incas, reflejan mi propio camino espiritual hacia Machu Picchu, al ser combinadas con documentos de Bingham y otros documentos de archivo que pude encontrar, estos cuentan una historia diferente. Estas personas no sentían un amor por mi país, o un interés por su gente, sus motivaciones eran las mismas que los conquistadores, la búsqueda de aventuras, de riquezas, de prestigio y de fama sumadas a su falta de entendimiento del lenguaje o de las muy diferentes culturas que existen en mi país con sus particulares cosmovisiones.

Cada pieza trata de algún aspecto particular de la expedición, haciendo hincapié en su relación con la comunidad local, así como el proceso que conllevo a Machu Picchu a convertirse en una de los destinos más exóticos del mundo. En este proyecto también incluyo las fotos etnográficas que el médico de la expedición de Bingham tomo a los pobladores Cuzqueños, todos ellos/ellas fueron llevados a la fuerza para ser medidos y analizados por extraños. Solo me puedo imaginar lo horrible que fue, y lo poco o nada que significaron esas expediciones para ellas/ellos en donde no se les tomó en cuenta, excepto como ayudantes para el trabajo manual. Este es un proyecto que se encuentra aún en desarrollo.

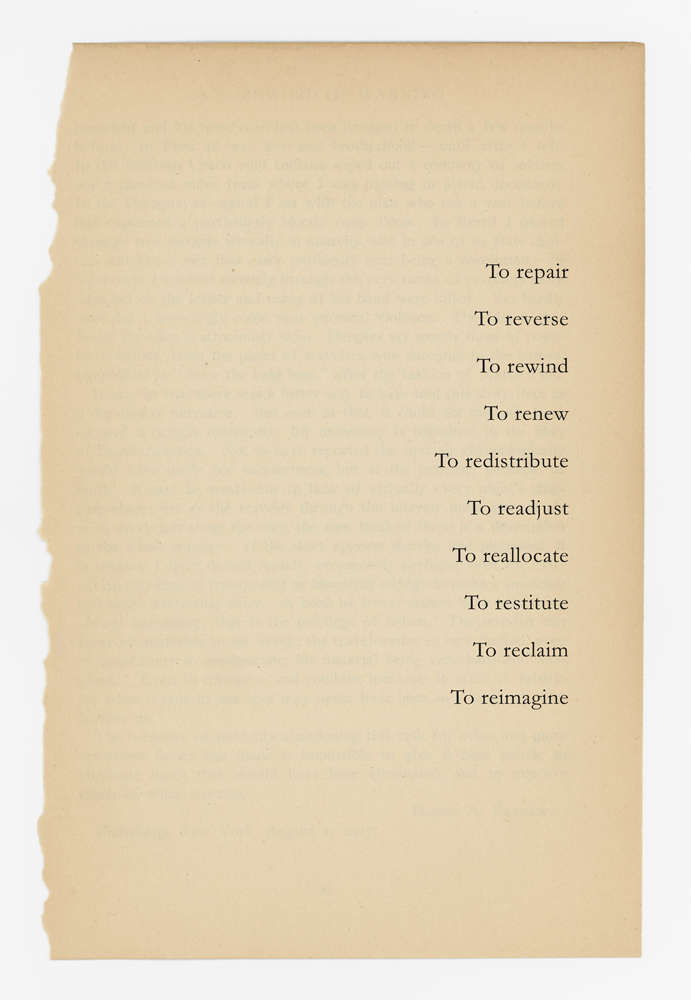

DG: I’m interested in your approach to “retelling” history through this project, and taking ownership over that which was removed. You mention the Peruvian relics being returned to their rightful owners, so how does this work function similarly? What does it mean to you to tell this story?

CRG: I think it is important to vindicate our history, to expose what really happened because if we do not do it but wake up and realize that in part we continue to be exploited or exploiting, we will not be able to create equity in our society. We have just lived through a presidential election where my country was split in two, both groups insulted each other, and the racism and classism that always existed was then openly exposed on and exacerbated by social media.

How can we build the country we want and repair our wounds if our story is only told by groups in power? It is time to expose exploitative models that have been preserved from the colonial period to the present, dismantle our official history that is not inclusive and rebuild our national identity by recovering the stories from the point of view of all the communities that exist in our country.

James Baldwin very aptly said that “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.”

DG: Me interesa tu enfoque para “volver a contar” la historia a través de este proyecto y hacerse cargo de lo que se eliminó. Mencionas que las reliquias peruanas están siendo devueltas a sus legítimos dueños, entonces, ¿cómo funciona este trabajo de manera similar? ¿Qué significa para ti contar esta historia?

CRG: Pienso que es importante reivindicar nuestra historia, exponer lo que realmente sucedió porque si no lo hacemos sino despertamos y nos damos cuenta de que en parte seguimos siendo explotados o explotando no vamos a poder crear equidad en nuestra sociedad. Acabamos de vivir unas elecciones presidenciales en donde mi país se partió en dos y ambos grupos se insultaban los unos a los otros, se exacerbó el racismo y el clasismo que siempre existió, pero ahora expuesto abiertamente en redes sociales.

¿Cómo podemos construir el país que queremos y reparar nuestras heridas si nuestra historia solamente es contada a través de los grupos de poder? Es tiempo de exponer modelos explotadores que se han conservado desde la etapa colonial hasta la actualidad, desmontar nuestra historia oficial que no es inclusiva y reconstruir nuestro imaginario nacional recuperando las historias desde el punto de vista de todas comunidades que existen en nuestro país.

James Baldwin dijo muy acertadamente que “La historia no es el pasado. Es el presente. Llevamos nuestra historia con nosotros. Somos nuestra historia.”

DG: This set of images is part two of a larger, four-part project titled, Mi País Imaginado. How does this work fit within the larger context of these series?

CRG: Ariella Aisha Azoulay’s book is divided into chapters focusing on imperial actors such as historians, museums and photographers. I use a similar classification to develop the chapters for my project Mi Pais Imaginado. Being a photographer, I could not exclude photography as an ideological tool, as an imperial apparatus, I constantly think about the privilege of owning a camera and losing the right to your own image.

Recently, I saw the Irving Penn exhibition (online) at MoMA, which showed photographs of Cuzco people posing very awkwardly for the camera. One of those photos recently sold for over half a million dollars at a Christie’s auction. I thought, What is the difference between that photo and an ancient Peruvian relic that is displayed in a museum? There is no difference; some people go to Peru and bring relics, others bring photographs. So this is part of the same conversation we need to have because this is still happening today. Privileged people with cameras are still photographing BIPOC bodies and benefiting from that. A good example is the photograph that Steve McCurry took of Sharbat Gula that sent her to prison and endangered her life.

DG: Este conjunto de imágenes es la segunda parte de un proyecto más amplio de cuatro partes titulado Mi País Imaginado. ¿Cómo encaja este trabajo en el contexto más amplio de estas series?

CRG: El libro de Ariella Aisha Azoulay está dividido en capítulos enfocados en actores imperiales como los historiadores, los museos, los fotógrafos. Yo utilizo una clasificación similar para desarrollar los capítulos para mi proyecto Mi País Imaginado. Siendo yo una fotógrafa, no podía excluir la fotografía como herramienta ideológica, como aparato imperial, constantemente pienso en el privilegio de poseer una cámara y el perder el derecho a tu propia imagen.

Recientemente, vi la exhibición (en línea) de Irving Penn en el MoMA, donde mostraba fotografías de personas Cuzqueñas posando muy torpemente para su cámara, una de esas fotos se vendió recientemente por más de medio millón de dólares en Christie. Pensé: cuál es la diferencia entre esa foto y una reliquia peruana antigua que se exhibe en un museo, no hay diferencia, algunas personas van a Perú y se traen reliquias, otras se traen fotografías. Entonces, esto es parte de la misma conversación que necesitamos tener, esto todavía está sucediendo hoy, personas privilegiadas con cámaras todavía están fotografiando a personas BIPOC con mucho éxito para ellos, un buen ejemplo es la fotografía que Steve McCurry tomo a Sharbat Gula, por la cual fue encarcelada poniendo en peligro su vida.

DG: This project addresses broader issues related to colonial exploration and the looting of cultural artifacts—many of which are still being held at major museum and institutions. How do you feel this work contributes to the dialogue and need for reclamation of these items?

CRG: Indeed, the main reason I am working on these projects is to continue these conversations. Institutions that possess Peruvian artifacts and relics should include a more complete history in the legends. Certainly not all artifacts were looted; some collections were bought legally, some were gifted, some were sold during wartime, and some were sold in the absence of an appropriate state policy to withhold exportation.

I am a realist and I know that the return of many pieces is not possible, but it seems to me that the museums that have Peruvian collections have an obligation to tell the story correctly and not stereotype Peru and its people, and more importantly, understand that the people who created those pieces and their cultures are still alive and their descendants are still alive in Peru. They are not relics of the past; they are people of flesh and blood and it is they who should be asked how they want the artifacts of their ancestors to be remembered and exhibited. It is important to include their histories and to accept that in many cases the artifacts should never have left Peru, in particular the funeral bundles and human remains. We need to start the conversation honestly. History is not our fault, but it is our responsibility. We need to have the courage to look at our past and act.

DG: Este proyecto aborda temas más amplios relacionados con la exploración colonial y el saqueo de artefactos culturales, muchos de los cuales aún se conservan en importantes museos e instituciones. ¿Cómo crees que este trabajo contribuye al diálogo y la necesidad de recuperación de estos elementos?

CRG: Si, efectivamente, la razón principal por la que estoy trabajando en estos proyectos es para continuar estas conversaciones. Las instituciones que poseen artefactos y reliquias peruanas deben incluir una historia más completa en las leyendas. No todos los artefactos fueron saqueados, eso es seguro, algunas colecciones se compraron legalmente, otras fueron obsequiadas, algunas se vendieron durante situaciones de guerra y otras se vendieron en ausencia de una política estatal apropiada para retener la exportación.

Soy realista y sé que la devolución de muchas piezas no es posible, pero me parece que los museos que poseen colecciones peruanas tienen la obligación de contar la historia correctamente y no estereotipar al Perú y a su gente y más importante entender que las personas que crearon esas piezas, sus culturas siguen vivas y sus descendientes siguen vivos en Perú, no son reliquias del pasado, son personas de carne y hueso y son a ellos a los que se les debe preguntar cómo quieren que los artefactos de sus ancestros sean recordados y exhibidos, es importante incluir sus historias presentes y aceptar de parte de las instituciones que los artefactos muchas veces nunca debieron salir del Perú, en particular los fardos funerarios y restos humanos. Necesitamos empezar la conversación honesta, creo yo. La historia no es nuestra culpa, pero es nuestra responsabilidad. Necesitamos tener el coraje de mirar nuestro pasado y actuar.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026