James Prochnik: Far Apart

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Far Apart by James Prochnik.

James Prochnik uses photography as a means to explore the world outside, focusing on people, place, memory, and the poetry of the everyday. James’s lifelong interest and love for photography turned into a serious pursuit in 2015 following a career as a creative partner in a firm that created custom large-scale paintings and sculptures for architects and interior designers around the world. In the years since, James has had photographs and photo series published by the New York Times, Vice Media, Fortune, USA Today, and SHOTS magazine, and exhibited in galleries across the country. In 2019 James launched ‘NYC Photo Community’ – a weekly newsletter listing photography events, workshops, exhibitions, and opportunities for photographers everywhere. James has been a regular guest lecturer at the University of Vermont on Ethics and Aesthetics in Street Photography, and is currently teaching photography online for StrudelmediaLive.

James publishes a weekly email newsletter listing upcoming photography events, talks, exhibitions, and news called the NYC Photo Community. This October, James will be teaching a 5-session online class that will cover many of the techniques and thought processes used to make the Far Apart series.

Far Apart

“There are gaps in the mesh of the everyday world, and sometimes they open up and you fall through them into Somewhere Else. Somewhere Else runs at a different pace to the here and now, where everyone else carries on.”

-Katherine May, Wintering

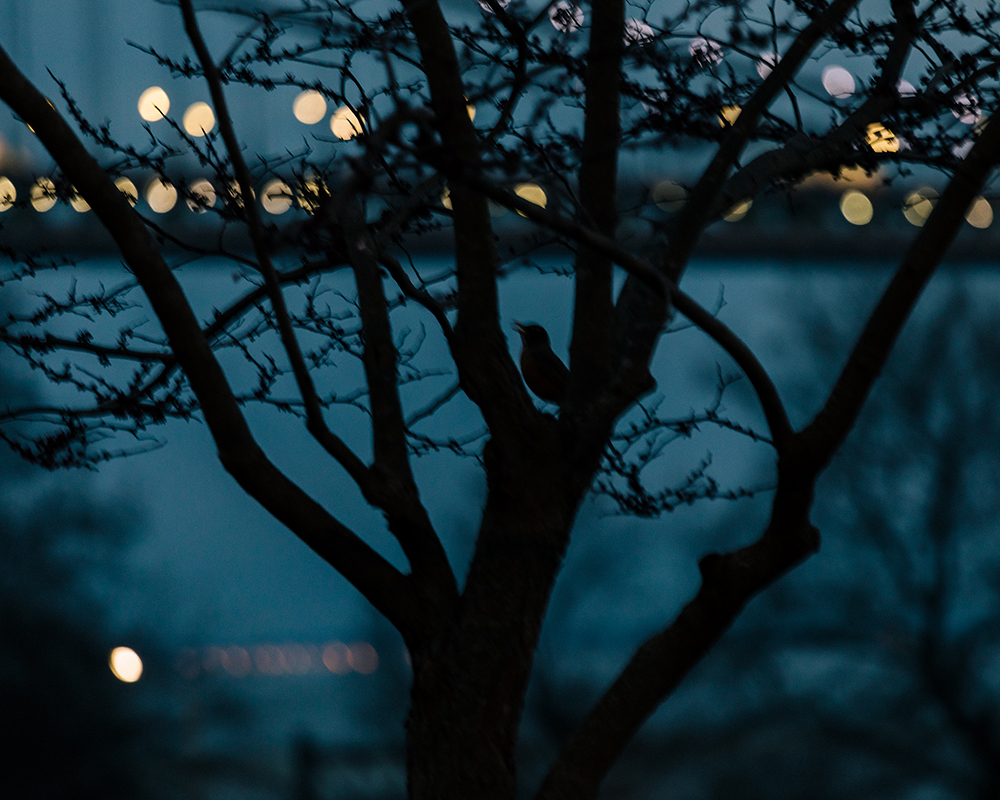

Far Apart is a pandemic love letter to Shore Road Park, a narrow strip of playgrounds, wooded paths, and ball fields in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. It’s an urban green space sandwiched between a dense residential neighborhood on one side and a six-lane highway on the other. Along with bird songs, you hear the roar of drag racing cars on the highway and jet engines from planes heading to LaGuardia and JFK overhead. Mixed in with flowers and landscaping are discarded plastic bags and wind-blown trash. And yet – during a brutal period in a sickened and socially isolated city, this park I had largely taken for granted in years before was enough. Enough to calm doomscrolling-induced anxieties. Enough to provide bountiful moments of staggering wonder and beauty and delight (and sometimes horror). In what felt like the most unlikely place, portals opened up and transported me to different worlds.

Daniel George: To begin, what drew you to photograph within these urban greenspaces? And what were you looking to find in your photographic explorations?

James Prochnik: The pandemic sent me into these green spaces. I used to make most of my photographs on busy city streets. I love the energy and excitement of being immersed in a rush of people. That was no longer an option, and early on I spent a lot of time inside doomscrolling social media. I did get out for regular walks though, and was surprised how quickly my neighborhood park calmed my anxieties about the world. I carried my camera with me on these walks but had no idea what I was looking for. It was springtime and it was reassuring seeing the earth return to life with such force and familiarity in contrast to the unpredictable changes the pandemic brought. So I made pictures of these colorful spring and early summer scenes, but without a sense they could amount to anything. One day I saw a vine reaching out several feet past the wrought iron fence it had climbed, searching blindly into empty space for something to cling to. I felt like the vine, blindly searching my surroundings for something new to photograph. It was frustrating, and at some point, I stopped bringing my camera and just walked through the landscape looking. It was only then that the idea for the project began to resolve. I started to see the park as a place of wonder and healing, a place of almost sci-fi strangeness. and occasionally, a place with disturbing or shocking revelations of its own. Albrecht Dürer has a painting called ‘A Great Piece of Turf’ that is literally that – a clod of earth, with grass and plants growing from it. And yet, in its complexity and beauty, it seems to reveal a whole universe. I wondered if I could find a universe in my park, my great piece of turf?

DG: There have been studies that indicate walks in nature, despite how mediated, can improve cognitive functioning. I am interested in the theme of sanctuary, and how your work depicts individuals finding refuge. What is your personal experience on the topic?

JP: I come from a family of walkers, and a family who appreciated and valued nature as a place of refuge and restoration whether that was family vacations out west, or just on simple afternoon walks in the small park near my childhood home. I remember being entranced by Frances Hodgson Burnett’s classic children’s novel, The Secret Garden, where a garden that had been a locus of great pain for its owner becomes a place of mental and physical healing under the loving care and attention of the children who re-discovered it. My great grandfather James Putnam even founded an Adirondak mountain camp with philosopher William James as an explicit antidote to the stresses of the rapidly industrializing society of the mid-1870s. So these ideas weren’t new or controversial to me, but after many years of living in the city without many trips away, I rarely felt a great absence of expansive nature in my life. Although not as extreme, I felt some kinship to Frank O’Hara who said, “One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one needs. I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy, a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life.” The pandemic was the first time I really felt the loss of a larger nature in my life, and I was very grateful for the small slice of nature my local park offered. It really did feel like a sanctuary to me, and I could see many other people felt the same way.

DG: Despite the proximity to busy highways and densely packed neighborhoods, adding the soundtrack of planes overhead, I get a sense that respite is attainable. Many of the photographs are very peaceful. Yet you also add reminders of a brutal reality—exemplified by scarred trees and animal remnants. What were your intentions with those contrasts?

JP: The sights and noise of city life are part of this park. Trash blows in from the adjacent neighborhoods. You’ll see squirrels enjoying junk food like pizza or muffins. Car or plane noise is everpresent. At the park’s edge, trees are roughly constrained by iron fences. Nevertheless, within those metal bars respite is attainable, and that was one of the revelations I had making the work. Despite so many impediments to the beneficial powers of nature, the powers still worked. So I wanted to describe this accomplishment, while not shying away from the disturbing and even shocking realities I also noticed. Horror is part of nature. The pandemic was likely a ‘natural’ event. In a talk photographer Mark Steinmetz once gave, he quoted Robert Adams as saying something along the lines of, “Show affection for the world, but don’t lie about it.” I tried to follow that ethos.

DG: The majority of images that include people have a sort of religious feel—as if they are caught in moments of reverence or worship. Talk about your choice to depict these people in this manner.

JP: It’s not uncommon to see people enraptured by small moments inside the park. I saw people bathe almost luxuriantly in the glow of the setting sun, listen raptly to a bird singing its last song of the day, and lose themselves in the fragrance of spring blooms. I tried to catch these moments, sometimes candidly, and sometimes after conversations with the people. Some moments of reverence were explicitly religious, like the man in one of my photographs using a small patch of grass by the highway to kneel in prayer. I felt like in these moments people were truly transported. It’s how I often felt in the park.

DG: Considering that these photographs were made over the past year during the pandemic, what did it mean to be in those spaces at that particular time? And perhaps for your subjects as well?

JP: More than anything, being in these spaces, particularly after viewing the world as presented by internet news or social media, felt just incredibly reassuringly normal. Families played with their children and held outdoor birthday parties. Kids played soccer and baseball. People flew kites. The apocalyptic world being so vividly fed to us on our phone screens evaporated, and a real word of normalcy, of life going on, of children growing up, reasserted itself.

The pandemic was only one of many ongoing crises that shaped my experience of the park at this time. These images were also made during the time of Black Lives Matter protests, climate crisis, and other great political conflicts across the country which prompted significant reflection and consideration of things like the role systemic racism, money, and political power had in shaping the apportionment of green space in my park and across the city. In this sense, the reassuring normalcy of the park was not reassuring at all, just another manifestation of privilege and power in an unequal society.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026