Wendi Schneider: On Beauty

On Christmas, I love to share a project or a practice that celebrates beauty. I didn’t have to think long and hard to consider an artist who has a legacy of creating work that unabashedly reinterprets the natural world in ways that make us slow down, take a deep breath, and relax into wonderment. Wendi Schneider’s photographs are sanctuaries for the soul, respites from the strife and turmoil that the world presents us with. Her photographs remind us that the natural world is waiting for us, to bask in it’s magic…and yes, beauty.

Schneider’s work could be considered contemporary Tonalism, a soft focus, luminous approach to landscape that was popular after the civil war. The fragility in her fragile, glowing, and quiet images, turn us inward, away from the tangible world into an intangible space of emotion and reflection. Writer Alexxa Gotthardt shares in a recent article on Artsy “While Tonalism’s cloudy surfaces and somewhat enigmatic connotations may have propelled it out of favor in the early 1900s, it’s precisely these characteristics that appeal to scholars and viewers today. An art that can feel inscrutable, on one hand, is also ripe for investigation, analysis, and consideration. After all, at their core, Tonalism’s hazy, enveloping scenes were fueled by a desire to calm the turbulent recesses of the mind and—in the process—open it to deep contemplation.” In the past several years, Schneider has mastered working with precious metals. She pairs her glowing images with frames she has amassed over years of collecting.

Prior to her career as a fine art photographer, Schneider brought similar sensibilities to her editorial and advertising photography. She is also is a collector of art and objects from the turn of the 20th century massing her own significant collection of primarily Art Nouveau, Arts & Crafts and photogravures. She lives, breathes, and celebrates photography, is an advocate for her community and a supporter of countless artists and institutions. And Schneider brings a high level of excellence to all she creates.

An interview with the artist follows.

Wendi Schneider is a Denver-based visual artist widely known for her ‘States of Grace’ series – combining photography and precious metals to create illuminated impressions of vanishing grace in our vulnerable environment. Schneider’s images seemingly dance on the paper’s surface amidst reflections of light on precious metals, creating a synthesis of technique and subject. Schneider has worked over the decades in fine art photography, advertising and editorial photography – including book covers and the original Victoria Magazine – design for print and web, art direction and marketing, and has been a collector of art and objects since the 1970s.

Exhibited worldwide – including AIPAD and Art Basel – her work has been published, awarded, and collected internationally. Schneider’s photographs are held in the permanent collections of the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Center for Creative Photography, the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, the Auburn University Library Special Collections, the Try-Me Collection, and numerous private collections. She is represented by A Gallery for Fine Photography (New Orleans); Arnika Dawkins Gallery (Atlanta); Catherine Couturier Gallery (Houston), Galeria PhotoGraphic (San Miguel de Allende), Rick Wester Fine Art (New York City); and Vision Gallery (Jerusalem).

Follow Wendi on Instagram: @wendischneiderart, @states_of_grace_, @the_schneider_collection

States of Grace

My work is rooted in the serenity I find in the sinuous elegance of organic forms. I’m transformed in capturing the stillness of the suspended movement of light and compelled to preserve the visual poetry of these fleeting moments of vanishing beauty in our vulnerable environment. I photograph intuitively – what I feel, as much as what I see. Informed by a background in painting and art history, my images are layered digitally with color and texture to manipulate the boundaries between the real and imagined, and are often altered within the edition, honoring the variations. Printed on translucent vellum or kozo, these ethereal impressions are illuminated with white gold, moon gold, silver or 24k gold on the verso, creating a luminosity that varies as the viewer’s position and ambient light transition. My process infuses the artist’s hand and suffuses the treasured subjects with the implied spirituality and sanctity of the precious metals – echoing the moment of capture and ensuring each print is a unique object of reverence.

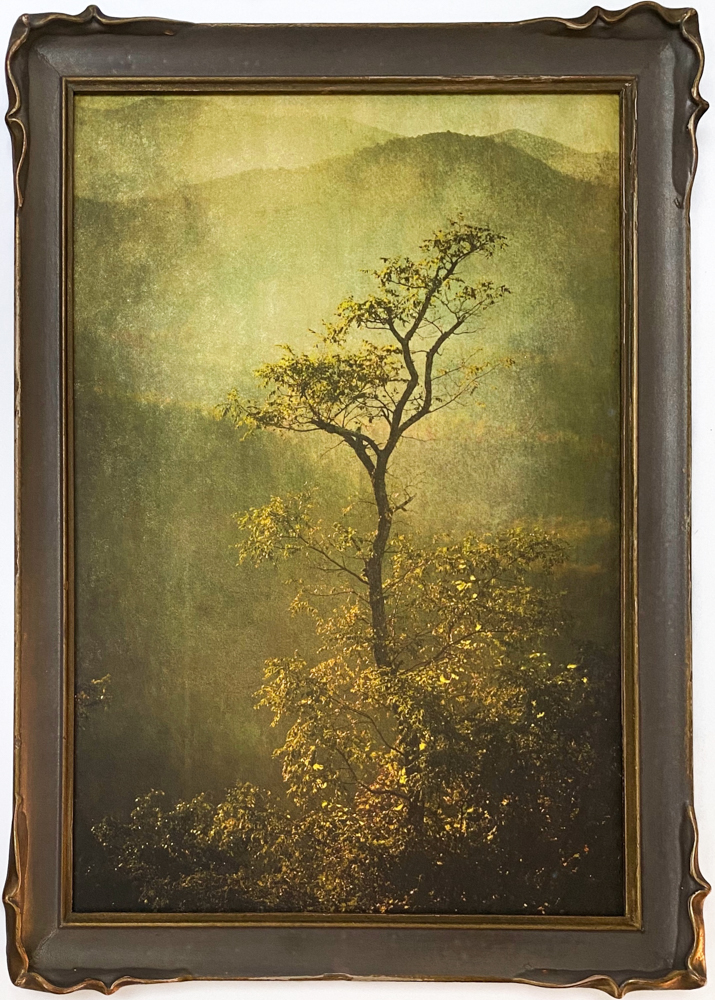

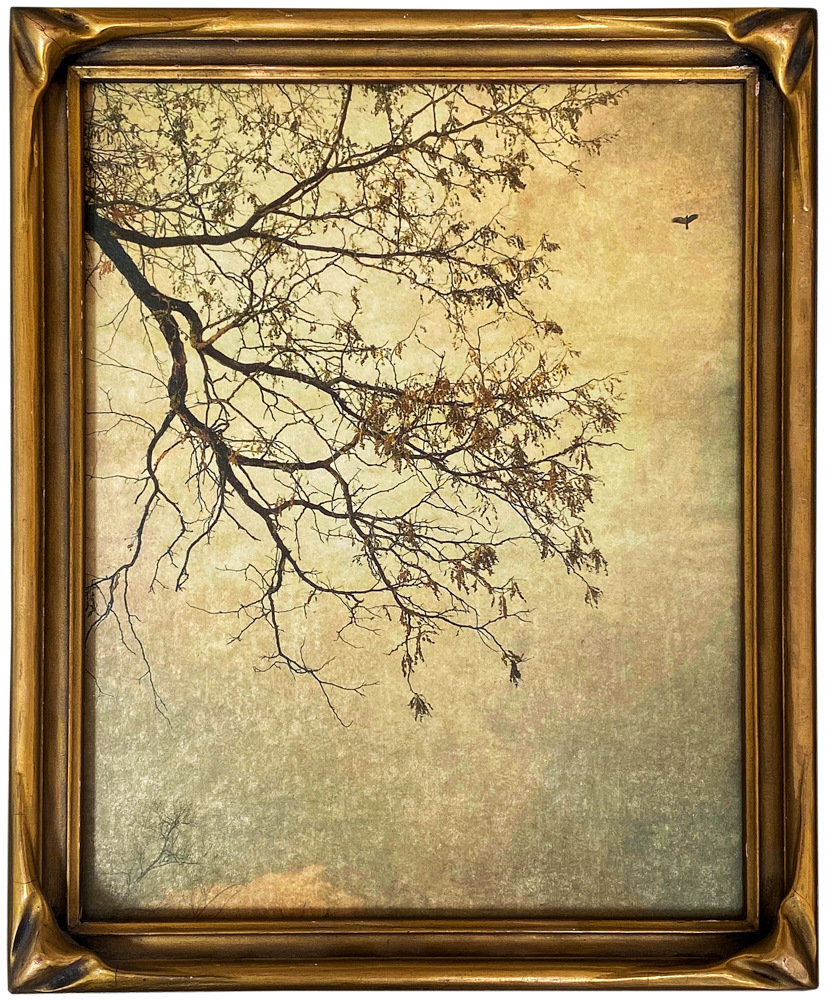

The Patina Collection

The Patina Collection is an assemblage of gilded prints in the States of Grace series paired with antique frames – the synthesis of 40 years of collecting turn-of-the-twentieth-century art and objects and creating images inspired by the sinuous elegance of organic forms. The serpentine shapes are echoed in the subjects I photograph and the undulating curves of the Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts frames that house these works.

Congratulations on your myriad of successes! Please share the landscape of your growing up and what brought you to photography.

Thank you! I grew up in the plush Southern beauty of Memphis. It was lush with old oaks, magnolias, and maples with diaphanous wafting angels’ wings. I recall the sounds of scattering leaves and quivering grasses in the breeze, the cushiony softness of running barefoot through the lawn, the melancholy light at dusk, and the air before the rain, followed by the enveloping scent of moist bark and greenery.

Our neighborhood was developed around the time our house was built in the ‘50s, but scattered among the houses were a few lovely old homes on larger acreage. We were fortunate to view one through our bedroom window, past the spot where we buried critters who met an unfortunate demise, and the trees that separated our yards. In my earliest outdoor memory, I’m eating lunch at their grand garden table with benches, which I remember as marble, though could well have been concrete. I found solace beneath the venerable weeping willow that backed up to the neighbor’s little farm behind our house, and we were often serenaded by the great horned owls that lived there as we drifted off to sleep. When I was nine, they paved paradise.

My mother and grandmother painted in oils when I was young, and childhood friends tell me that I drew and dabbled in watercolors a great deal more than I recall. I definitely doodled my way through school. I spent hours in the attic perusing my mother’s art history catalogs from The Met, diligently attaching stickers of each artwork in their proper place. The images were small, but they made a big impression. I watched a lot of old films and still do.

In many ways, my formative years were the thirteen spent in the New Orleans I had fallen in love with as child eating beignets on a balcony overlooking Royal Street. I finished college at Newcomb painting late into the night, and it was in New Orleans, while working in marketing at The Times Picayune, that I bought a camera to create references of models for my paintings. I quickly realized I could express myself more eloquently with a camera than a brush. I was mesmerized by the alchemy of the emerging print in the darkroom and often pushed the film to make the photographs more closely resemble drawings. Missing the aroma and sensuousness of oils, I soon began painting on my gelatin silver prints.

Much of your early career was working as an editorial photographer for magazines and book covers. Can you tell us about that period in your life and how your early work informs the work you make today?

My path was a circuitous one, echoing the flowing forms of many of my subjects. I loved working within the parameters of assignments and had the good fortune to work with incredibly talented editors, art directors and stylists on lavish shoots in beautiful locations for Victoria Magazine, but mainly I worked alone in my apartment. I often propped and styled my own shoots, especially for book covers. I switched to color slide film for most of the editorial work, since the hand-painted look was not always appropriate. Much of my work was photographed with grainy Scotch slide film or pushed to create more painterly images.

Looking back, my work has always seemed to be about finding grace, beauty, and transcendence in the details. The rhythmic, sinuous lines of those swaying willow branches from my childhood re-emerged in the sensuous lines of the flowers and women in my hand-painted work, and later in the undulating ribbons and pearls of my still life and fashion images for editorial. I’m still calmed by the balance of a good composition. For many years I photographed on a tripod. When I began shooting for myself again, and with the advance of digital, I’ve embraced the fluidity of photographing hand-held.

How would you define your work and style?

My work is a celebration of the senses anchored in the visual — an exploration of my spiritual connection to our vulnerable natural world and to the transcendence found in nature’s timeless beauty in our tumultuous times. It grounds me. I create illuminated illusions — impressions of feelings from moments of capture through creation. It’s intuitive and meditative, both adoration and obligation. For me the original capture is often just the starting part of the process. While my early prints were layered with oils, this work is layered digitally with color and texture to manipulate the boundaries between the real and the imagined. I’ve always been more interested in how something feels than how it appears. The effect of color is a deeply emotional part of my work, and I continue to experiment with combinations of color and various precious metals. Unlike traditional printmaking, I don’t complete an edition at one time, and the color, texture and leafing is often altered within the edition, depending upon how I feel that day. I suppose you could define my work as pictorialist, tonalist, impressionist, naturalist, spiritualist, expressionist, symbolist, environmentalist, or perhaps self-portraitist, as I believe art reflects the soul of the seer.

When did you begin using metals in conjunction with your photographs?

I began gilding in 2012. When I reconnected with A Gallery in 2010, I saw Louviere and Vanessa‘s monumental resined gilded work. Inspired by Klimt, I had worked with gold oils on my paintings in the late ‘70s, and I was intrigued by the idea of incorporating gold into my photography (although I must admit that after seeing Jeff and Vanessa’s stunning work, I felt I should probably never make another photograph). In 2012, I took a platinum and gold leaf workshop with Dan Burkholder in the upstate New York area memorialized by the Hudson River painters. We only spent a little time on leafing and printing on vellum, but it was all I needed to experiment with the process. I began with 24K gold owls and insects, and incorporated white gold and silver when I returned to figura and fauna. I didn’t want my work to be about the gold, but to engage the artist’s hand and suffuse my subjects with the implied spirituality of the precious metals, imbuing them with the heart-fluttering connection felt at capture. I think of each print as a unique object of reverence.

I have watched your career explode in the last few years, garnering galleries and exhibitions. What do you credit your success to? Have you shifted your approach to marketing?

Luck and friendships have a lot to do with it. Shortly before I left New Orleans for New York, a dear friend insisted I meet Joshua Mann Pailet of A Gallery For Fine photography; I had spent hours at A Gallery absorbing the photographs, but I was too intimidated to speak. Joshua was supportive of my early work and began representing me soon after I moved to New York in 1988. I continued creating fine art and editorial work until the mid ‘90s. I disliked the gloves and masks required for painting while pregnant with our son, so I spent many years working in advertising and portrait photography for clients, web and print design, and art direction.

In my mid 50s, I began to feel the pull to return to my personal work. After reconnecting in 2010, Joshua watched the ‘States of Grace’ series develop and invited me back into the gallery. I felt I was starting over: I had not worked in the fine art world for many years, and it was a vastly different landscape. I tentatively began entering juried exhibitions in 2008, and more vigorously in 2012 and, eventually, in 2015, I attended one of the receptions. It was at The Center For Fine Art Photography, where I was warmly greeted by Executive Director Hamidah Glasgow, and I began connecting with other photographers and later with gallerists who I would eventually work with. I traveled to more juried exhibits and portfolio reviews to get my work in front of people in the industry and to connect with the community that is so supportive of us all. I’ve had multiple incarnations of my website over the years and have embraced social media as an important part in connecting and sharing work.

I know you are a devoted collector of photographs, can you tell us about your collection and your new instagram account?

The happiest times I spent with my mother when I was young were when we were haunting antique shops, and that love for antiquing and collecting flourished over the decades. My beloved Nana was born in 1900, and I’ve always been drawn to that period. I began collecting in earnest once I had my own place in New Orleans and continued when I moved New York in 1988 — primarily Camera Work photogravures and early platinum prints, pottery, china, textiles, paintings, light fixtures, prints, boxes — the gamut. Over the years I’ve added to the collection. I wanted to raise awareness of the collection as I feel it’s an important part of who I am and the art I make, and as I’m not sure what I will do when the day comes to deaccession. It’s marvelous work that I want to expose others to who may not be familiar with some of the art or artists. I love to discover both new and old work and relish researching the creators, the histories, and the connections. There are a few contemporary photographers in my collection as well — so along with images and books by Steichen, Stieglitz, Coburn, Käsebier, Brigman, Sudek, Atget, Demachy, and others, there are those by friends Dawn Surratt, Amanda Smith, Kat Moser, Sarah Hadley, Constance Rosenthal, Keith Carter, Lori Vrba, Herman Leonard, and more.

What is the happiest part of the journey for you?

For as long as I can remember, I have found sanctuary in the focus of flow – those moments when everything else disappears and I am completely absorbed in the creative process. I’m transformed in capturing those graceful organic forms. It’s a spiritual connection that elevates me to another realm – those magical moments when the senses align – when my eyes and essence are engaged and intertwined. I crave the concentration and connection that comes with looking intensely for the spirit of a subject and photograph intuitively from my heart. I’m then transfixed when layering the images. Making the prints and gilding can be frustrating at times, but I enjoy the meditative process of creating, so I suppose the happiest part of my journey is the entirety of the creative process, where I’ve found refuge since childhood.

Where do you find inspiration? What artists’ work do you revisit?

I think everything we see and experience remains in our subconscious to later emerge in our work, consciously or otherwise. I’m still drawn to the elegant whiplash lines of Art Nouveau, which I first remember seeing in the My Fair Lady movie. The rich, romantic paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, Ingres and Manet were influential on my early work figurative work, O’Keeffe’s flowers, the artists in Madeleine Pinault’s exquisite book The Painter As Naturalist, which I’ve cherished since the early ‘90s, and the studies of Dürer and da Vinci. While many of the historic studies were drawn or painted on vellum made from calfskin, the vellums I use are cellulose-based.

The spare, essential lines of the Japanese printmakers and painters I first saw in my mother’s art history catalogs — that influenced so many of my photographic heroes at the turn of the twentieth century — still inspire me. I’m surrounded by a rotating selection of photographs from my collection, and while I don’t create work inspired by specific images, there is no doubt that my interpretations are influenced by the exquisite tonalities of the Pictorialists. The early work of Steichen is probably the biggest influence, along with Coburn, and Tonalist painters like Whistler; also Sargent, Monet, and countless other painters over the centuries. I love viewing new and historic work on Instagram, and I delight in my daily Lenscratch fix.

Anything new on the horizon?

I’ve been dealing with degeneration in my neck but I’m adapting and working vertically as much as possible, albeit more slowly. I’m in my fourth year on the board of the Colorado Photographic Arts Center, under the leadership of our dynamic Executive Director and Curator Samantha Johnston. We are thrilled to be moving into an amazing new space in 2023, hopefully in time for our next Month of Photography exhibitions, portfolio reviews and the organization’s 60th anniversary.

For the last several years, even prior to the pandemic, I have mainly been communing with the trees in our neighborhood, mostly at random, except for my obsession with the coffee trees next door, which I view daily from my bedroom window. The ‘States of Grace’ series is the over-arching theme of all of my work and within the series are collections grouped by subject, theme or treatment. The trees of Park Hill may become another collection in some form. I continue to create prints for my collection of antique frames in the Patina Collection and to add images to the Evenings with the Moon collection, engaging the moon as muse to express our shared longing for freedom, peace, love, and harmony amidst the chaos of the world. This synthesis of form and content, paired with poetry and music, encourages the viewer to consider the commonalities in our collective consciousness. We all live under the same moon.

In 2020, I cautiously traveled to my sister’s home in the mountains of North Carolina for some much needed pandemic forest bathing and I’m excited to begin to share that work in the ‘Into the Mist’ collection.

I’m looking forward to my most exciting year ever of exhibitions! I’m premiering ‘Into the Mist’ at my first solo show at Rick Wester Fine Art in New York, opening January 27. I’m delighted to be working on my second solo exhibition for A Gallery For Fine Photography in New Orleans, opening March 4. That will be followed by my first solo exhibition at Arnika Dawkins Gallery in Atlanta with a selection of images from ‘States of Grace,’ which opens March 25; then on to Houston for my second solo exhibition at Catherine Couturier Gallery, where we will feature ‘Into the Mist,’ opening April 9th. I hope to cross the pond for the opening of The Royal Photographic Society 163rd International Photography Exhibition, where I will have two gilded photographs among the 100 chosen from 8000 for the exhibit opening April 16th in Brighton before it travels. Then on to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico for a two-person exhibition with my friend Lori Pond at Galeria PhotoGraphic, which opens May 7th. I’ll also be sending new work to Vision Gallery in Jerusalem.

I’ve also begun working on the surface again, and I’m moved each time I return my mother’s easel. It accompanied me from Memphis to New Orleans, New York and Denver and reminds me of where the great gift of art originated. I’m filled with gratitude and taken full circle.

Into the Mist

In ‘Into the Mist’ I offer glimpses of respite amidst the vague unknowing in the time of COVID. I ventured to the mountains of North Carolina as summer ended in 2020 to find a reprieve in shinrin-yoku as the Japanese call forest bathing – seeking serenity and balance as practiced by a multitude of cultures for thousands of years. A quiet pilgrimage among the trees revealed the beloved fog that comforted me as a child growing up in the South. Embraced in a vapor evocative of the melancholy light of dusk, it was as though the clouds sighed an amorphous, dewy veil over the lush woods. I felt outside of time as we drove along the winding road, photographing through the windshield, windows, and myriad layers of love and loss. Moving and still – it was a blink in the continuum of history, in a period like no other in our lifetime.

Cloistered in my studio upon my return to Denver, I was transfixed in transforming these fragments of time. Informed by my background in painting and art history, the images were layered digitally with a limited palette of color and texture to evoke the mystery and wonder that permeated my senses, delicately enhancing the muted verdant views.

Printed with archival pigment inks on Japanese kozo paper – made from the inner bark of mulberry trees – white gold leaf was then applied on the verso, infusing the artist’s hand and suffusing the image with the implied spirituality of the precious metal. The filtered, dappled light that glimmered through the branches is echoed in the shimmer of the gilded prints. With this meditative process I explore what I feel as much as see. Elevating the ephemeral, I follow intuitively where each image takes me, honoring the variations within the edition. Senses enveloped, I am immersed in a state of grace.

>div<

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026