Medium Festival of Photography: Brenda Biondo

Today, we are continuing to look at the work of artists whose work I discovered at this year’s Medium Festival of Photography. Up next, Brenda Biondo’s project, A Legacy of Shadows.

Brenda Biondo is a American artist who uses traditional camera techniques and a formalist aesthetic to explore the perception of atmospheric light and color and their role in the construct of landscape. Her images engage the phenomena of sunlight to provide a framework for our meditative experience of being in nature, while challenging viewers’ perception of color and three-dimensional space. She often uses unconventional contexts to demonstrate how traditional photography can still show us new visions of common subjects. Her interest in atmospheric phenomena and other components of the natural world is informed by her degree in journalism and her previous career as a writer specializing in environmental issues.

Brenda’s work has been exhibited throughout the country and published in numerous publications, including The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. Her photographs are held in many private and public collections, including those of the Library of Congress, the Museum of Photographic Arts, the Denver Art Museum, the Center for Creative Photography and the San Diego Museum of Art. A solo exhibit of her work opened at the San Diego Museum of Art in 2017. Her first book of photographs, Once Upon a Playground, was published by the University Press of New England in 2014 and is now the subject of a six-year traveling exhibit organized by ExhibitsUSA.

A native New Yorker, she’s been a resident of Colorado since 1999. She currently lives in the small town of Manitou Springs, in the foothills of Pikes Peak, where the light and landscape continue to inspire her work.

Brenda’s project, A Legacy of Shadows is on view through September 3rd at the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art in partnership with the Center for Fine Art Photography.

Follow Brenda Biondo on Instagram: @brendobiondo

A Legacy of Shadows

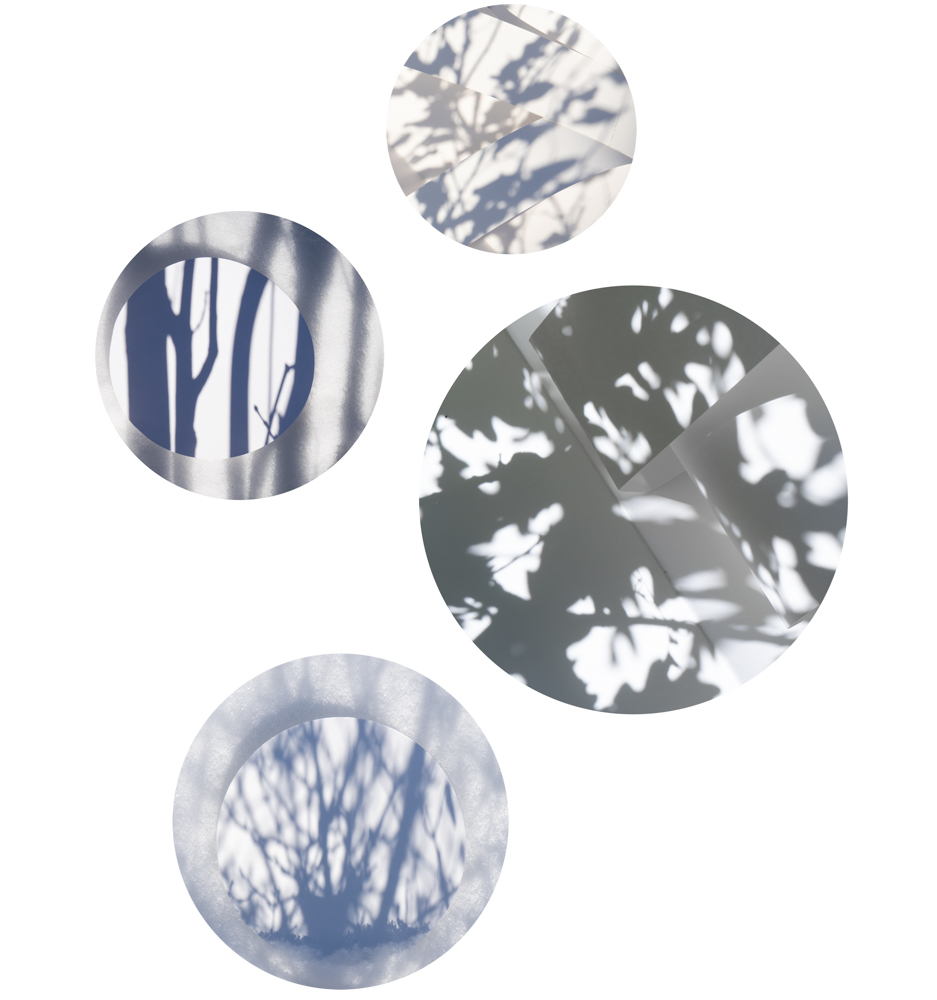

A Legacy of Shadows is a series of traditional in-camera photographs that evoke the fracturing of nature and the poignancy of acknowledging beauty in a time of destruction. The layers of shadows deconstruct/reconstruct the landscape while referencing efforts to control and constrain nature. By featuring shadows rather than the plants themselves, the work alludes to the greatly diminished state of the natural world – a world that is essentially a shadow of its former self.

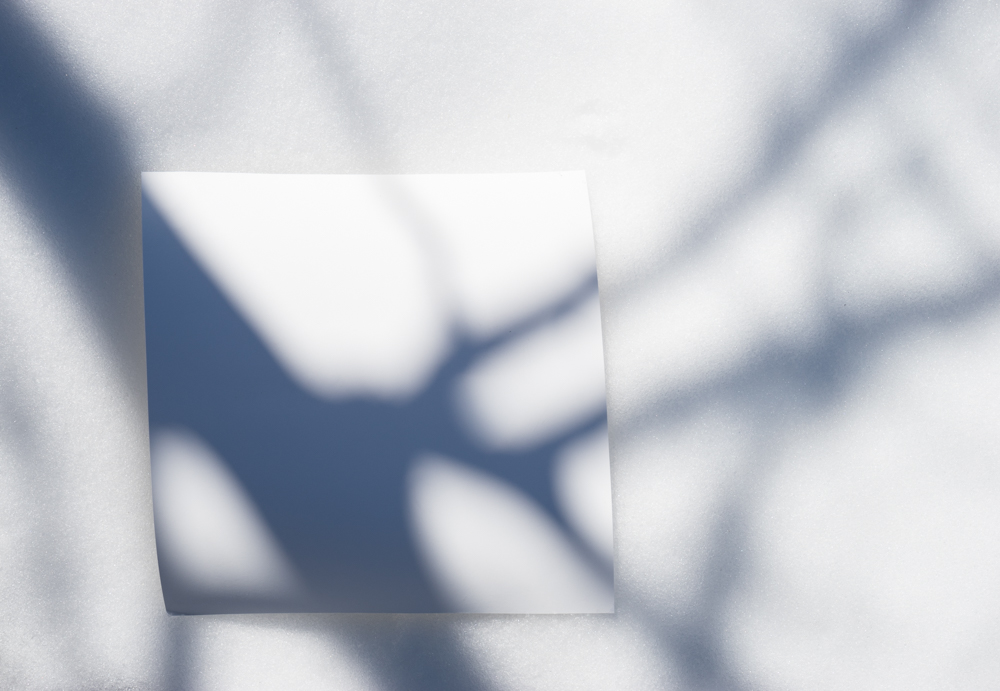

To create these images, I place rolled, cut and/or folded pieces of blank white paper on the ground and take photographs of shadows cast by trees and other plants in the landscape. The blueness of the shadows is a natural result of the geographic locations where the photographs are made, since areas of high-altitude and/or exceptionally clear air allow greater scattering of sunlight’s blue wavelengths, causing ambient light to produce colored shadows. The angles of the paper dictate the hue and luminosity of the shadows.

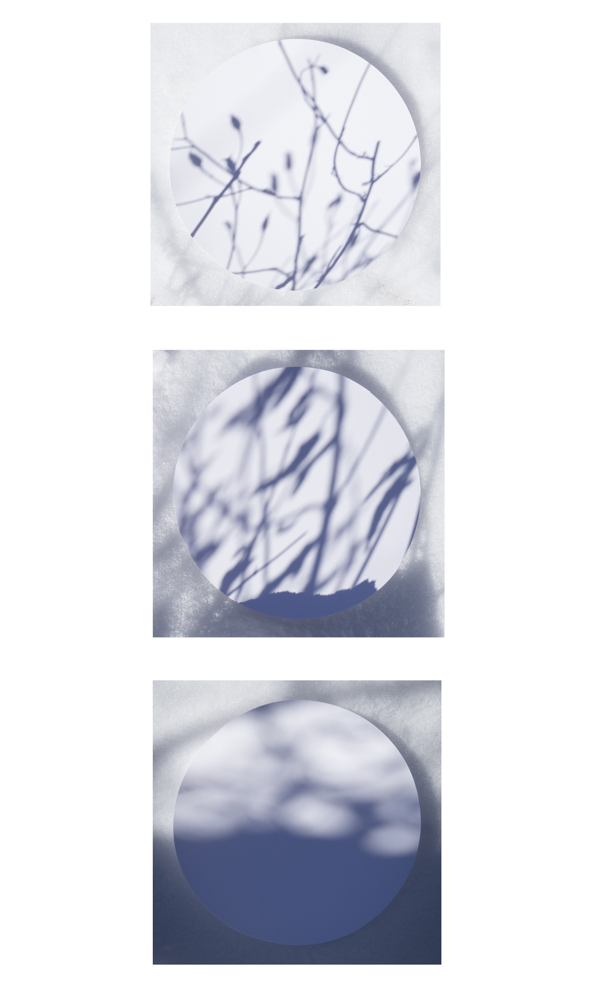

Images in this series were photographed at high altitude in my home state of Colorado as well as at sea level in southern France during an artist residency. The images were made in wild areas as well as in urban greenspaces in order to acknowledge plants’ crucial role in cooling the planet and increasing the livability of the world’s cities. This work also expands my previous focus on atmospheric light and color by allowing me to document atmospheric phenomenon (the scattering of blue light) by looking down at the ground rather than up at the sky.

Daniel George: Tell us about the development of A Legacy of Shadows, and perhaps more broadly, your sustained interest in a formalist approach to exploring light and color.

Brenda Biondo: “A Legacy of Shadows” is a marriage of sorts between my interest in atmospheric light and color and my interest in the environment. Since moving to Colorado 23 years ago, I’d frequently notice how shadows falling on snow were often blue or purple. When I decided to research this phenomenon, I discovered it had to do with the same reason the sky is blue – it’s all about how blue wavelengths in sunlight bounce around in the atmosphere, especially at high altitude. Those blue wavelengths are literally bouncing all around us, although that’s not usually apparent unless we see a shadow cast on something white (usually snow). By using plants in the landscape to cast shadows on white paper templates and sometimes also on snow, I’m able to create images that bring together two of the subjects I’m most interested in.

My interest in formalism goes back to my early love of modernist painting with its emphasis on color relationships, shapes and textures. It’s an aesthetic approach that is a critical part of all of my work. Thinking about the compositional elements of color, line and shape influences how I arrange blank paper into sometimes simple, sometimes elaborate constructions used in the “Legacy of Shadows” images. Then, by placing the paper template to catch the plant shadows in a certain way, and cropping the final image very precisely, I’m able to reveal a formal composition that has the desired structure, weight and balance.

DG: You mention that you use “unconventional contexts to demonstrate how traditional photography can still show us new visions of common subjects.” With that in mind, what sort of “new visions” revealed themselves to you throughout the creation of this work?

BB: Much of my work looks highly Photoshopped – yet the images are all in-camera traditional photographs.

The “Legacy of Shadows” work started as a novel way of looking at atmospheric light. The sky is one of the most common subjects out there – we see it every day. The series began when I realized I could look at atmospheric light and color by looking down at the ground instead of up at the sky. When I started exploring atmospheric light in this way, it was through blank white paper constructions placed on the ground, where the paper arrangements cast shadows on themselves. This earlier iteration of the work resulted in a small series called “Rayleigh Shadows.” “A Legacy of Shadows” evolved from that earlier work, and reveals a phenomenon of sunlight that’s often not apparent to most people.

Also, shadows are all around us as we walk through nature – but they become the background noise of whatever else we’re looking at. With this work, I wanted to bring those shadows to the forefront to look at a specific landscape in a very indirect way – to allow the audience to notice things that often go unnoticed, such as the shape of certain leaves, a plant’s structure, how vines tangle together, etc.

DG: Could you explain more about how your background in journalism informs your photographic work? What connections do you make with the way you are visually describing the environment through these images?

BB: I’ve been interested in wildlife and environmental issues for decades, and that was reflected in a pretty straight-forward way in my previous career as a freelance writer covering mostly environmental and conservation issues for newspapers and magazines. When I switched careers from writing to photography 20 years ago, I was determined to keep at least some focus on conservation issues, even though I didn’t intend to do photojournalism or documentary work.

What I’ve tried to do with both my writing and my photography is to show something new to the audience and to provide enough facts so that the audience has a better understanding of the subject’s importance. I think that’s one of the reasons photography has always been so appealing to me, compared to other art forms: it starts with some “facts” that are right in front of me. Of course, I control how I present these facts by how I arrange the subject, what I focus on, what I crop out, my overall style, etc. But my work is always based in reality: I’m not using Photoshop or any other post-processing to change what you see.

DG: This project brings to mind the tragic state in which the natural environment currently finds itself—as shadows can represent something fleeting, or lacking solidity or substance. You mention that these images “evoke the fracturing of nature” and recognize “beauty in a time of destruction.” In what ways do you feel they accomplish this?

BB: Having written about conservation and environmental issues for so many years, I feel like I have this burden of knowing more than the average person about how much damage we’ve done to the earth and nature – and how close we are to the tipping point of everything starting to collapse. Compared to even just 300 years ago, the world is just a shadow of its former self – which is one reason I wanted to create a vision of the natural world using only shadows of plants. And I use paper templates that break up and distort the shadows to reference how we’ve chopped up and constrained nature. On the other hand, I want my images to be beautiful because there’s still plenty of beauty in the world, and we should appreciate it and take comfort and solace in it while we can.

DG: You describe the meditative process, or experience of being in nature, as a framework of your visual explorations. How does your creative process correlate with this idea, and how is it manifest in your photographs?

BB: Being lucky enough to live in Colorado in a small town surrounded by open space, I’m in nature literally every day, hiking with my dogs, working on my laptop out on my deck, even driving to the grocery store and seeing the Garden of the Gods in the distance. And when I’m working inside, I’m usually next to a window that looks out at Pikes Peak and the foothills – so nature is in my field of vision for a huge part of my day. Which means I’m noticing things in nature constantly: how the color of clouds change, how the leaves catch the light at sunset, how the red rock formations contrast with the deep blue sky. But as beautiful as my surroundings are, I don’t want to present my audience with a postcard picture of it – I want to give a sense of the beauty in a more ephemeral way, without showing a particular tree or a particular mountain or a particular cloud. By not showing something literal, that beauty can be more universal to the viewer.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026