Photographers on Photographers: Alayna N. Pernell in Conversation with Allison Grant

This month we feature our annual Photographers on Photographers interview series. For this effort, we asked the 2021 Top 25 to Watch to share an interview with a hero, mentor, or an artist who has inspired them. Thank you to all who participated. – Aline Smithson

As of this past May, it has officially been 3 years since I graduated from my alma mater, The University of Alabama. Since then, my journey as a photographer, and subsequently, as a person has had a myriad of highs and lows. Yet to this very day, whenever I reflect on where I’m at now in my career and where I came from, I still find it hard to believe that I would be the photographer and educator that I am today had it not been for the genuine belief in me and the guidance of one of my photography professors, Allison Grant.

Allison Grant is an artist, writer, curator, and Assistant Professor of Photography at The University of Alabama. Her work has been widely exhibited at venues across the United States including the DePaul Art Museum, the Weston Art Gallery, the High Museum of Art, and many more. She has also curated exhibitions at venues both domestically and internationally such as the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Photoforum Pasquart Biel, and more.

Thankfully, we have kept in touch over the years, and I was thrilled at the opportunity to interview Allison for Lenscratch’s Photographers on Photographers interview series. Over the last several weeks, I have had the great honor of learning more about Allison both as a photographer and as a human being. I also had the great pleasure of learning more about her current ongoing body of work, Within the Bittersweet.

I couldn’t be more excited to finally share our conversation with you.

Allison Grant is an artist, writer, curator, and Assistant Professor of Photography at the University of Alabama. Her artworks have been widely exhibited at venues including the High Museum of Art (Atlanta); DePaul Art Museum(Chicago); Patti & Rusty Rueff Galleries at Purdue University (West Lafayette, IN); Edelman Gallery (Chicago); and the Weston Art Gallery (Cincinnati), among others. She was named on the Silver Eye Center for Photography’s 2022 Silver List. Grant received the 2020 Portfolio Purchase Award from the Atlanta Photography Group, the 2019 Developed Work Fellowship from the Midwest Center for Photography and was shortlisted for the 2019 FotoFilmic Mesh Prize. Works by Grant are held in collections at the High Museum of Art (Atlanta), DePaul Art Museum (Chicago), Columbia College Chicago, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation art collection, Cisco Systems Corporate Art Collection (Durham, NC), and the King County Portable Works Collection (Seattle).

Grant has curated exhibitions at venues including the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; Photoforum Pasquart, Biel, Switzerland; Filter Space, Chicago; and Atlanta Contemporary. Essays by Grant have appeared in Minding Nature Journal and INCITE: Journal of Experimental Media, Volume 7, as well as numerous artist publications and exhibition catalogs. Grant holds an MFA from Columbia College Chicago (2011) and BFA from the Columbus College of Art and Design (2004).

Follow Allison Grant on Instagram: @allie__grant

Bittersweet

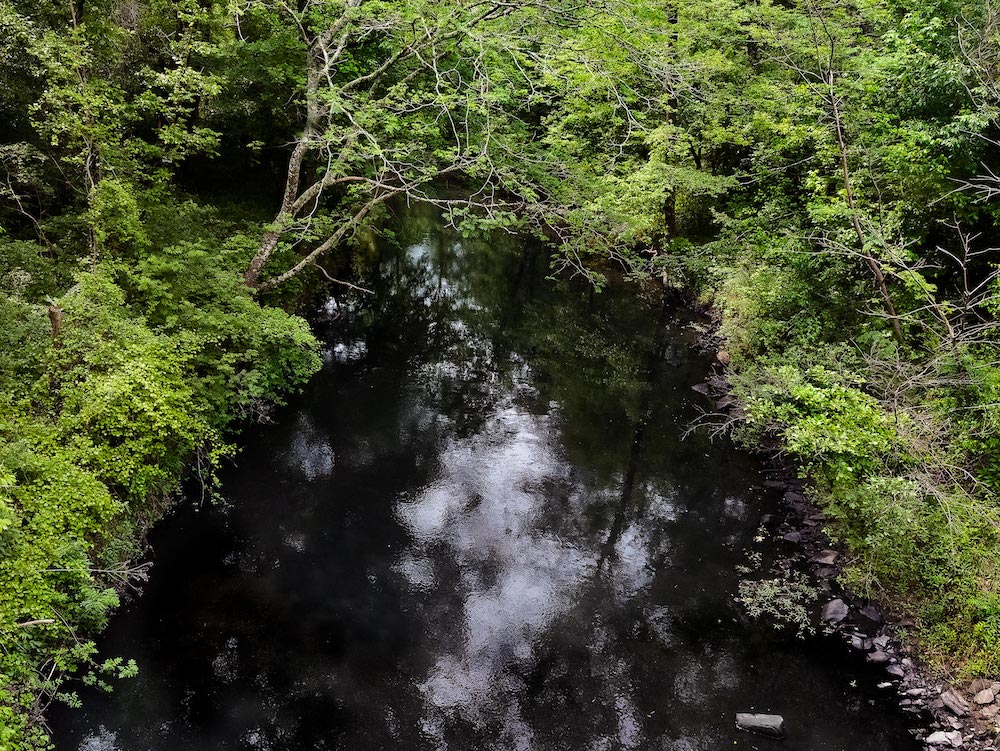

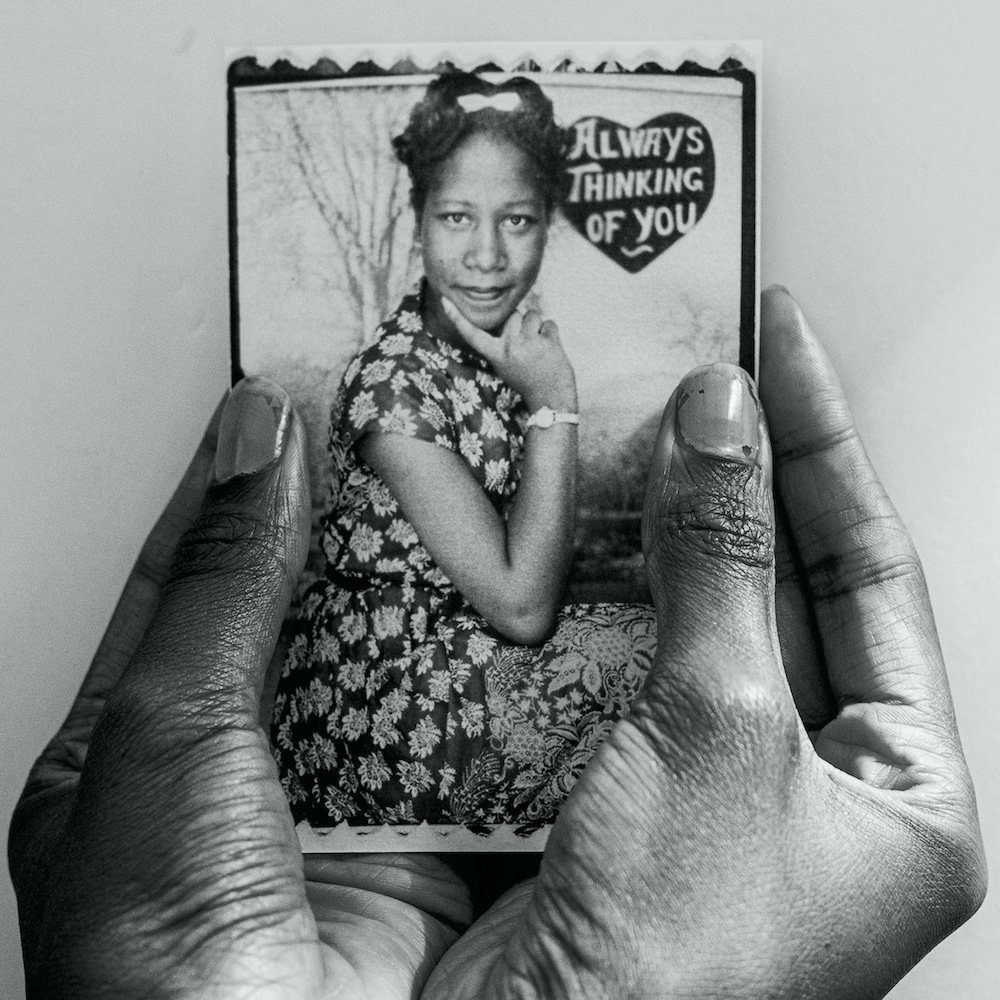

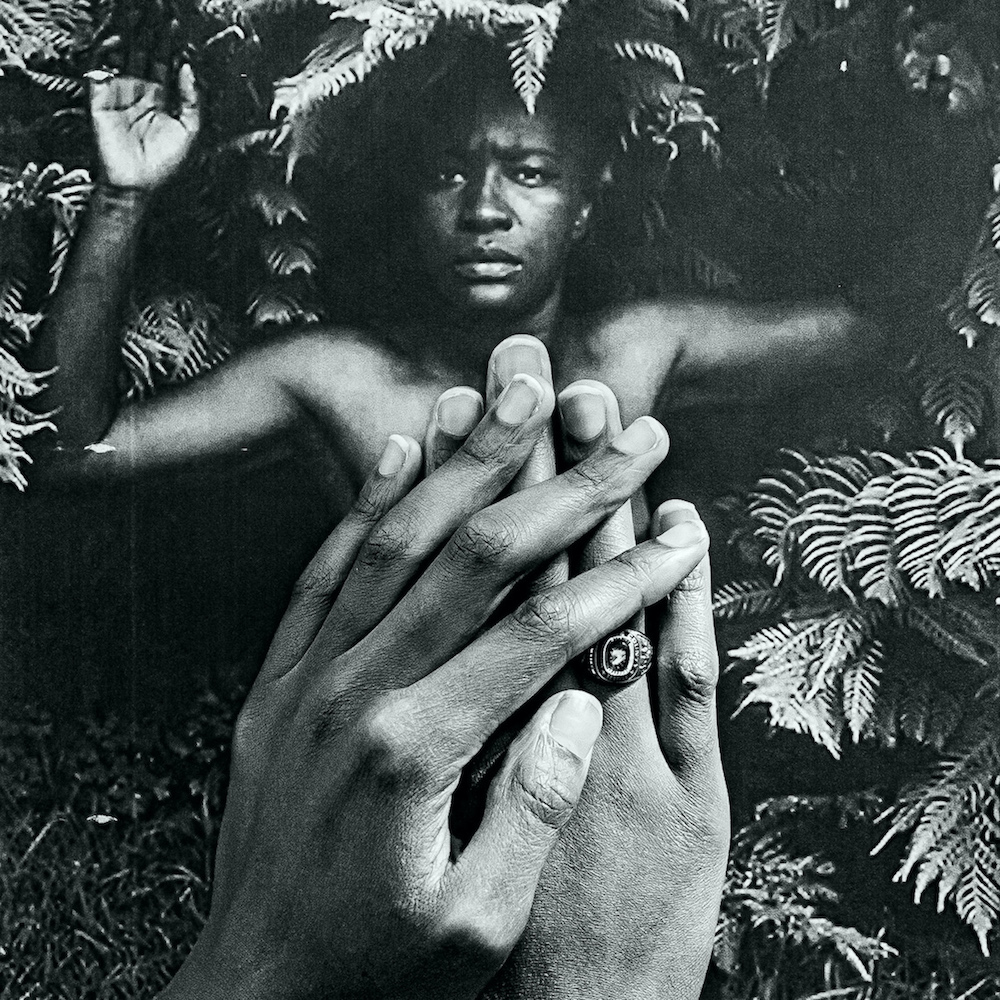

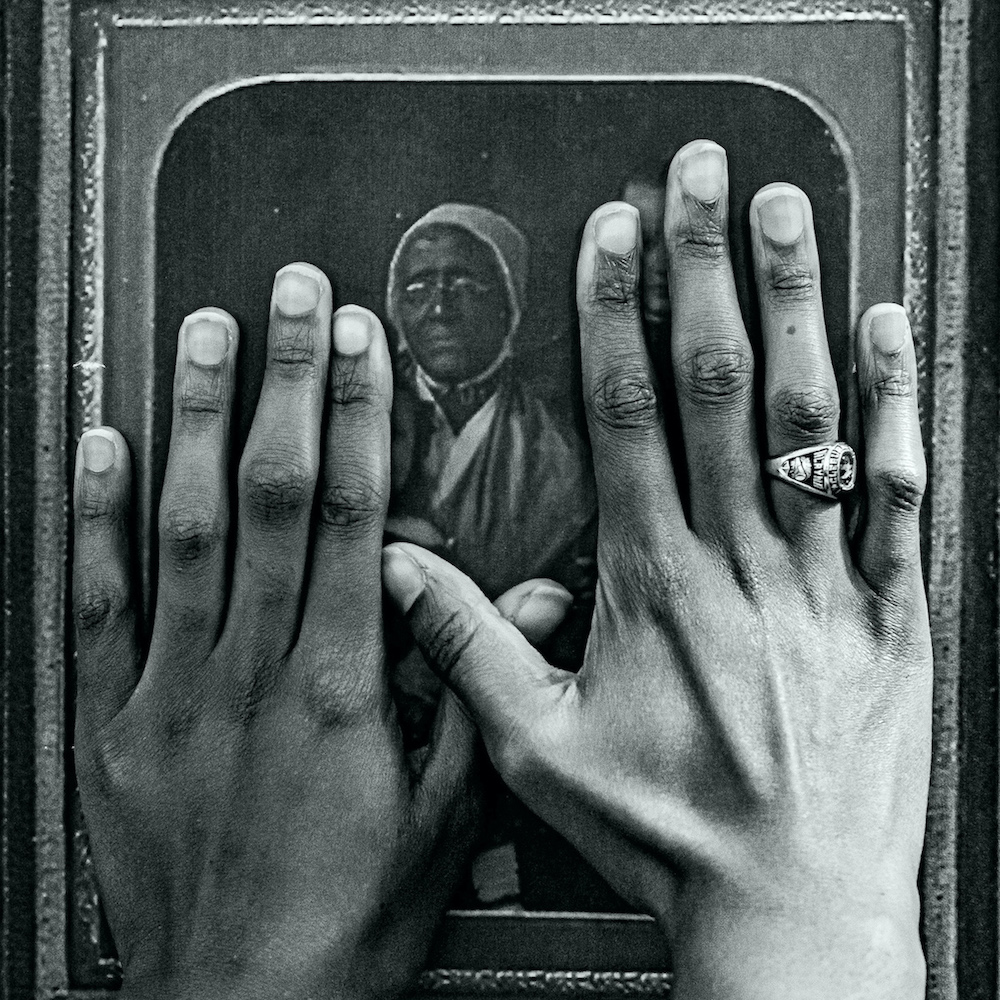

Within the Bittersweet is a dark, pastoral narrative about raising my children amid concerns about the impacts of climate change and environmental contamination. The photographs in the project were taken in and around my home in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, where dense vegetation and natural beauty intersect with industrial and fossil-fuel facilities that dot the region. These industries spread noxious particulates and hazardous toxins across the terrain and into the air, water, and our bodies.

In my artwork, the dark realities of the landscape we live in are interlaced with representations of my deep love for my children and the physical world around them—a living tapestry of incredible complexity that my daughters are just coming to know. The climate crisis will undoubtedly reshape the world they inherit, and through these photographs I negotiate the beauty and heartbreak of raising them on a wondrous planet in the midst of such rapid and impactful change. -Allison Grant

Alayna N. Pernell: To begin, tell me about yourself outside of the scope of being a photographer.

Allison Grant: It’s funny, so much of who I am as a person ends up woven into my photographs, so there’s a lot of overlap.

Being out in parks and wild spaces has always been an important part of my spirituality and mental health. Maybe it’s because I grew up in a house on several acres of forest and spent my formative years playing and dreaming in the woods. Now that I’m a parent, I get to take my seven- and four-year-old daughters along on many of my adventures in Alabama, where we live, taking pictures as they, too, discover their identities out in wild spaces. I also love to garden and find healing and rejuvenation in the process of caring for plants.

I love thrifting and I’m always on the hunt for cool old stuff. Most of my clothes and furniture are second hand. Thrifting is a process of searching, remaking, and reimagining, and there’s a thrill involved that is similar to what draws me to photography. I love taking aspects of the world around me and reimagining or reworking their meaning or status to see what’s possible.

ANP: I love this. Apart from being a parent, I can relate so much. What was your journey like to becoming a photographer?

AG: I took a photography class in high school. I had this witty, wicked smart teacher, Dr. Miller, who could pull art magic straight out of weird kids like me. He made us feel like our idiosyncrasies were a superpower. He introduced me to Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, and Sally Mann, and I was hooked. Before I left high school, I knew I’d be making pictures for the rest of my life.

I went on to study photography at the Columbus College of Art and Design and then attended graduate school at Columbia College Chicago. During grad school, I interned at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, and was thrilled when they offered me a job in museum education and curatorial work when I graduated. I spent ten years at MoCP, while also teaching photography and art history part-time at Columbia College and exhibiting my own artwork. In those years, I worked in many different capacities with diverse and brilliant colleagues. I grew immensely, but at some point, I began to feel that something was missing. I was doing too many things and wasn’t able to make and exhibit photographs at the level I wanted to, so I left and took a job as an Assistant Professor of Photography at the University of Alabama, which is where I met you, Alayna.

I’ve been in Tuscaloosa for five years now, working on a project titled Within the Bittersweet about my experiences of parenting amid concerns about the impacts of the climate crisis and environmental contamination. I’ve recently started a new project about this region. Before moving, I couldn’t have imagined how significant this place would become to my photographic work, but it’s exciting because the Deep South is full of complex stories and I’m learning constantly.

ANP: That’s amazing. I’m so glad that your journey led to us crossing paths! Who are your influences?

AG: Sally Mann is an important one. Her family work evokes a type of discovery of self that I experienced growing up in the woods and creeks of Ohio, when one foot was still in childhood and the other was leaning towards adolescence. In motherhood, Mann’s pictures speak to me in even more intricate and layered ways. Justine Kurland has also done important work on the complex ways girlhood and womanhood relate to the landscape, adventure, and discovery out in wild places. I find LaToya Ruby Frazier’s moving use of personal and intimate storytelling alongside accounts of toxic exposure to her family and community to have meaningful resonance with some of the issues in my work.

Landscape photographers dealing with toxic contamination, climate change, and the passage of time have influenced me too. Richard Misrach’s uneasy use of beauty and his special way of describing the invisibility of toxicity is especially influential. Terry Evans, Victoria Sambunaris, and one of my mentors in grad school, Judy Natal, have been significant in this area as well. Curators Natasha Egan and Karen Irvine, whom I worked alongside for many years at MoCP, have curated exhibitions on personal narrative and landscape photography that have shaped my thinking immensely.

Literary works also inspire me. Everything I read by Rebecca Solnit feeds my mind and often my work, and poet Catharine Piece’s writing, especially a poem called “Anthropocene Pastoral,” has been very impactful. I return to Wendell Barry’s The Unsettling of America for the moving ways it talks about the importance of being connected to the land. There are many others. I’m always searching, growing, and learning from the wisdom of others.

ANP: Wow, so many wonderful influences. I’ll have to check out those literary works sometime myself. When did you get, what you self-consider, your first “break” as a photographer?

AG: Curator Laura Fatemi put three of my photographs in the group exhibition Climate of Uncertainty at the DePaul Art Museum in 2013. It was my first museum show, and my work was in the same gallery as photos by Edward Burtynsky, Toshio Shibata, and Chris Jordan. Being included in such a smart and insightful exhibition gave me a lot of confidence that I had a role to play as a fine art photographer engaging with the environmental issues of our time.

ANP: I would like to shift the conversation to fixating on your current body of work, Within the Bittersweet. I have spent a lot of time with your work, and each time I view your images, I feel a sense of awe and wonder at the beauty of the photographs and their allure. This body of work has several overlapping layers– the impacts of climate change, motherhood, in some ways sisterhood, and childhood innocence– all covered with a thick blanket of your care. Though at the same time, I also feel a sense of grief because that “beauty” is fading. In a way, it’s almost as if I’m viewing what’s remaining of a climate that is rapidly changing in a way that is unfortunate.

On to my question, I have been thinking about the shifts in your ideas that you may have encountered over time as you’ve continued to examine and address the impacts of climate change in your practice. Have your thoughts and ideas shifted with you now being in the Deep South versus being in the Midwest?

AG: Absolutely, my thinking has shifted a lot. Climate change is a much more acute problem now than it was fifteen years ago when I started thinking about it. In the South, the intense heat and humidity makes the specter of further warming especially unsettling. Climate migration from the coast is going to have a big impact here. On top of that, I live four miles from an oil refinery and Tuscaloosa is bisected by a river where barges carry coal and petrochemicals straight through the heart of the city. The Midwest, of course, has some of the same environmental problems, but everything feels a little more heightened and uneasy to me here.

ANP: In the 4 years that I lived in Tuscaloosa, I had no idea about the fossil-fuel facilities that were there, which is shockingly frightening. It’s frightening because I’m sure that there are a vast number of people beyond myself who were and still are unaware of these facilities and how harmful the pollutants they’re releasing are to the environment and peoples’ lives. How did you come to know about these facilities? What was that journey like?

AG: I think your experience is common. Most industrial activity is tucked out of view here, and at first I was unaware of it too. Then one day I was on my way to pick up my daughters from school and a big cloud of black smoke filled the air. A chemical plant that handles a carcinogen caught fire right behind the school playground. I didn’t even know the facility was there. Mostly out of instinct, I snapped the photograph A Chemical Fire 800 Feet from the School through my car windshield at a stop light.

After that, I started researching and photographing other industrial sites, guided by google satellite imagery, the EPA’s toxic release inventory, and information from environmental NGOs in Alabama. All of the photographs in Within the Bittersweet are taken within a 100-mile radius of my home—most sites are in Tuscaloosa County. Many images, like Petroleum Coke Storage Near the School, show toxic sites partially obscured by foliage to visually communicate how contamination is sometimes hidden in the Alabama landscape.

ANP: The moments in your photographs where your daughters are playing feel like a breath of fresh air. What feelings do you experience whilst photographing your daughters? Do these feelings differ when you’re photographing the environment itself?

AG: I’m glad you picked up on that. Pictures like Isa and the Creek Boys and Watching were taken spontaneously in moments when my family was enjoying time away from the stress of daily life. After I take pictures, though, I go through a process of digesting them on an emotional level. Parenting is, for me, this sacred act of carefully doing what you can to carry a developing human into the future. Some days my girls’ optimism and innocence is uplifting, and on other days it crushes me. It’s so difficult to reconcile the wondrous experience of watching a child find their path into adulthood with the knowledge of what they may be up against when they get there, especially if limited action is taken on climate change. For me, the playing pictures carry a little bit of that melancholy.

When I’m alone in the landscape, I can go to different locations and there’s a lot more discovery and unfamiliarity. There are places I’ve photographed where the scale and intensity of fossil fuel extraction is surreal. So much of modern life is built on dirty energy that people never see first-hand. To go to the source and see it for myself has been reality altering. It takes my breath away every time.

ANP: There are many things that I find astounding in this work. Though one thing that I find incredibly powerful is the way that you encapsulate the beauty that’s essentially left of your environment and the growth of your daughters while also continuously finding a way to literally point back to the complicated reality that the environment surrounding you is slowly succumbing to climate change. With that said, I’m curious about your process. Specifically, I’m curious about what you find as vital to have in your photographs and/or a part of your photographic process? Perhaps, in other words, do you have any parameters for yourself while image-making? If so, has that evolved over time?

AG: It’s a great question. I keep parameters, of course, to give the project form and make it cohesive. Beyond that, it’s moments when the photographs feel haunted by the passage of time, or the beauty and sorrow of being alive, that feel most powerful to me. I guess I’d call it a type of poetry—that’s the vital ingredient in my work that’s so hard to come by, but so deeply poignant when it’s there.

ANP: I can’t reiterate enough how I have truly learned so much through sitting and spending time with your work. Out of my own curiosity, what has your work taught you thus far?

AG: So many things, but one that has surprised me is the power of collaboration. I work with my kids and they bring surprises into my photographs that I never could have dreamed up. When I’ve collaborated with curators, scholars, and other artists, it often takes my work to the next level. And right now, we’re working together on this interview, and we’re learning about art and life from one another. Different minds and instincts can build really special things when they come together. It’s a lesson I hold onto as an antidote to my darkest thoughts about climate change. Togetherness is a space where we sometimes discover possibilities beyond what we can imagine alone.

ANP: As a side note to the previous question, how has your work influenced the way that you teach your students at The University of Alabama?

AG: We’re in a period of profound social disruption, and my students often want to use their artwork to talk about complexities found in the world today, sometimes at the intersection of their lived experiences. To make work like that and put it out in the world takes a lot of endurance and bravery. Allowing space for healing and renewal is so important to my working process, and I know it’s the same for my students, especially those working with difficult topics. I strive to see them as whole humans and remind them that it’s ok to address immediate needs or restabilize emotionally. In my early years of teaching, I think I was too punitive when students missed deadlines or didn’t perform short-term. My artwork has taught me that a portfolio is something larger than a due date or missed class, and I respect my students enough to teach with the grace that knowledge offers.

ANP: I have thoroughly enjoyed being in conversation with you and learning more about Within the Bittersweet. I know I say it ad nauseam when talking about my own work and even when I’m in conversation with my family and friends, but I truly have learned so much from you and I look forward to learning more over time. In many ways, you have impacted my life both as an artist and a person. So, thank you! Is there any news you would like to share with the reader or anything you have coming up soon that you would like to share, as a final note?

AG: I have so many exciting things lined up over the next year. I’m particularly eager to see two collaborative projects realized:

In November 2022, I’ll be mounting an outdoor video and sound installation titled Our Air in downtown Tuscaloosa in collaboration with artists Karen Brummund and Holland Hopson. The elements of the installation will respond to local air quality data by pulsing rhythmically, like breathing.

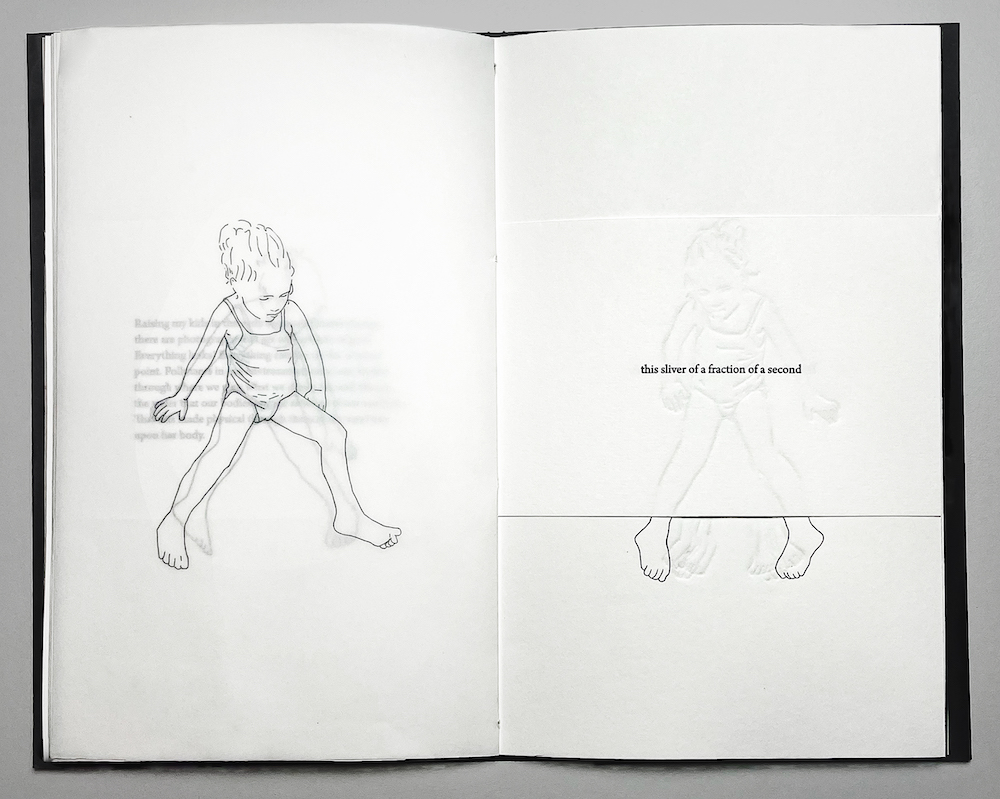

Sarah Bryant of Big Jump Press is collaborating with me on an artist book about my process called Acts of Translation: Allison Grant. It will be released in October of this year. It’s going to be stunning and I can’t wait to share it with the world.

I have a mailing list and I welcome all to join it for updates on my creative activities.

Alayna N. Pernell (b. 1996) is an interdisciplinary artist, researcher, and educator from Heflin, Alabama. In May 2019, she graduated from The University of Alabama where she received her Bachelor of Arts in Studio Art with a concentration in Photography and a minor in African American Studies. She received her MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in May 2021. Pernell’s practice considers the gravity of the mental wellbeing of Black people concerning the physical and metaphorical spaces they inhabit. Her work has been exhibited in various cities across the United States, including FLXST Contemporary (Chicago, IL), Refraction Gallery (Milwaukee, WI), JKC Gallery (Trenton, NJ), RUSCHWOMAN Gallery (Chicago, IL), Colorado Photographic Arts Center (Denver, CO), Griffin Museum of Photography (Winchester, MA) and more.

Pernell was named the 2020-2021 recipient of the James Weinstein Memorial Award by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago Department of Photography and the 2021 Snider Prize award recipient by the Museum of Contemporary Photography. She was also recognized on the Silver Eye Center of Photography 2022 Silver List, Photolucida’s 2021 Critical Mass Top 50, 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention, and more. She is currently the Associate Lecture of Photography and Imaging at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in Milwaukee, WI where she now resides.

Follow Alayna N. Pernell on Instagram: @alaynapernell

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Juliette Ludeker: Somewhere You Can Never GoFebruary 16th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026