Rich-Joseph Facun: Little Cities and Black Diamonds

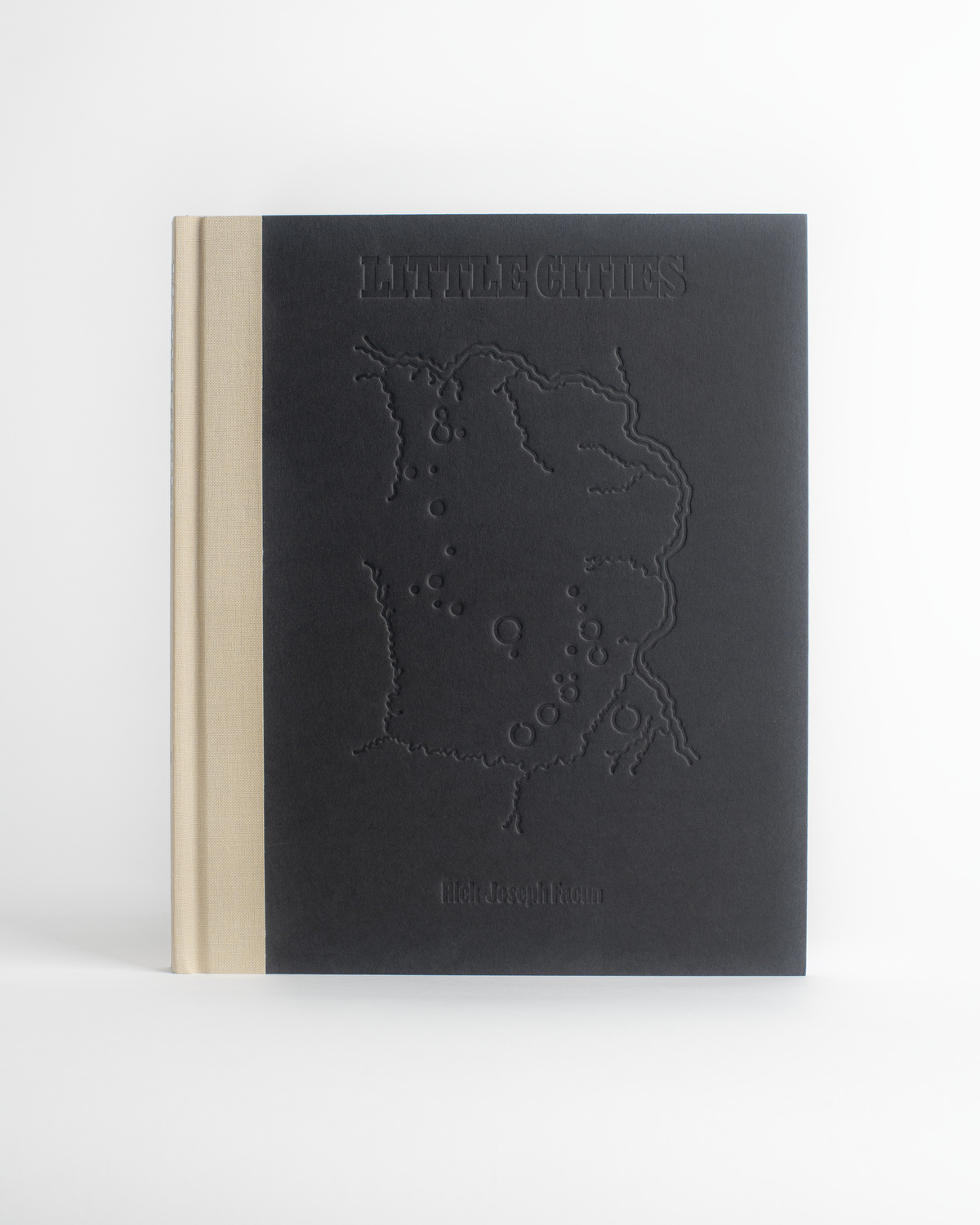

Rich-Joseph Facun’s beautifully designed and constructed second monograph, Little Cities (Little Oak.PRESS, 2022) opens with the words of American nature poet, William Cullen Bryant. This verse evokes sensations of sight, touch, and sound as the author meditates on times past. Of whom and what was before. This excerpt reverently sets the tone for the pensive nature of the photographs that follow—seemingly delineating both Facun’s experience in making this work, and an invitation to the viewer to participate by increasing their awareness to the subtlety of details to come. This series, Facun writes, is “a visual meditation on the ways cultural forces shape our relationship to the landscape. It examines how both Indigenous peoples and descendants of settler colonialists inhabited and utilized the land around them.” For me, Facun’s intent is succinctly represented early on in the book’s image sequence. Eight photographs in, and immediately following the title page, we are introduced to a scene of an earthen mound encircled by manicured suburbia. Having grown up in the American Midwest myself, I feel like this image somehow contains all the stereotypical identifiers that I associate with a middle(ish)-class residential area in that part of the country—brick and siding homes, flagpoles, precast plastic mailboxes, chain-link fences, and neatly maintained yards and roads. And the ubiquitous, understated beige car. By means of contrast in value, that car stands as a distinct focal point for my attention. I am intrigued by its mimicry of the shape of the mound behind it, yet how it is dwarfed in scale. I wonder about the individual inside and how they experience navigating the massive volume of space that the mound occupies. Do they even notice it? Or, has it become as ordinary and overlooked as the rest of their surroundings (including their car)? Are they aware of the mound and its historical and cultural significance? Whatever the case may be, at a certain point in their commute, as they approach the corner to turn left or right, they must acknowledge its presence. For me, this car-mound relationship illustrates the significance and function of Little Cities as a whole. The knowledge and awareness that the book extends symbolizes the earth mound in the neighborhood of the American cultural psyche—regarding the land and its uses, from indigenous inhabitants to the progeny of colonizers. Its existence is unavoidable and must, at some point, be addressed and reconciled.

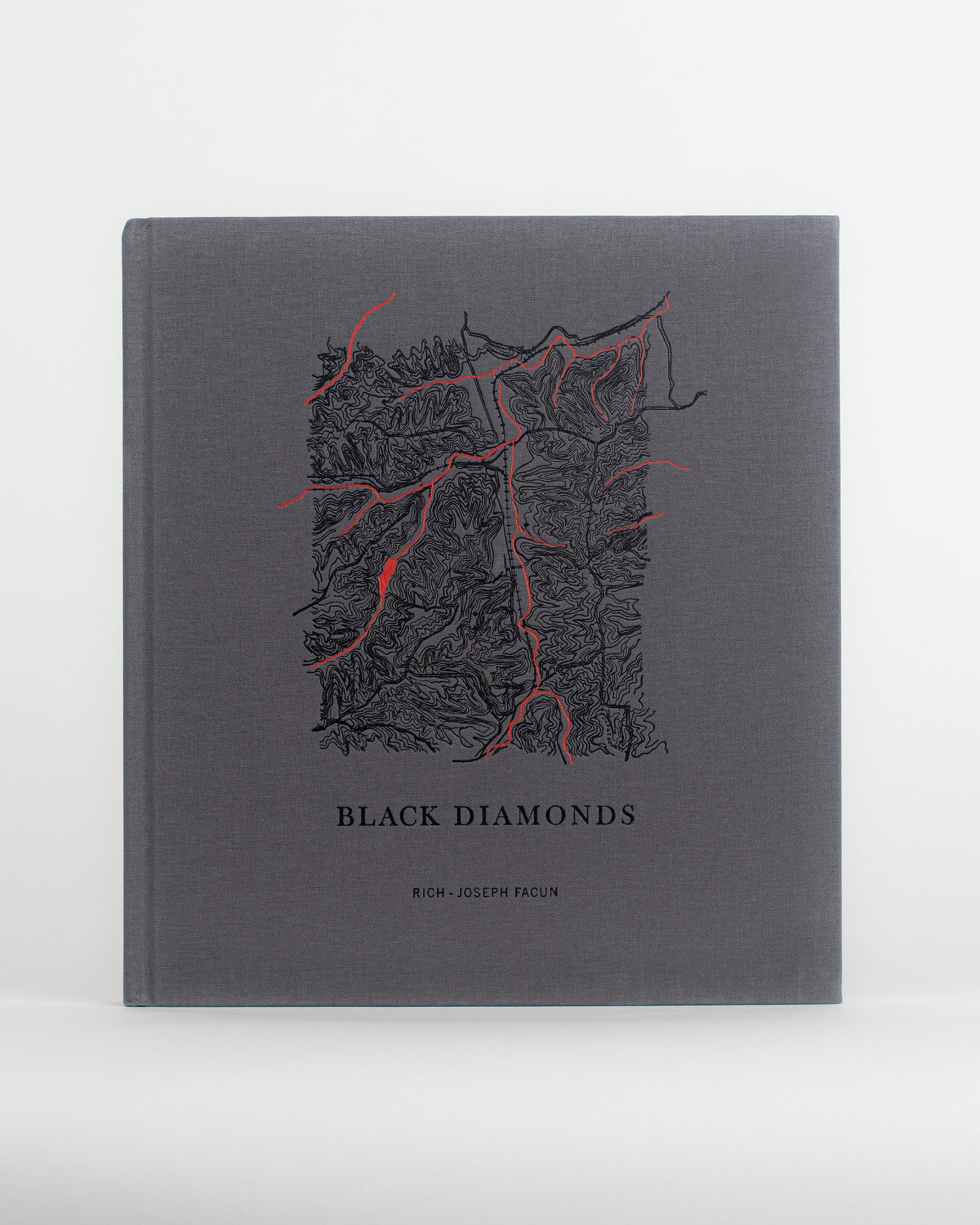

Little Cities is a continued investigation of the broader area that Facun now calls home—a personal exploration initiated with his project Black Diamonds (Fall Line Press, 2021). Both series borrow their names from the Little Cities of Black Diamonds region, or the small towns in the Appalachian foothills of Ohio. Where Little Cities centers our attention on land and place as it relates to history, Black Diamonds delves intimately into the contemporary culture of locals in these same places. Together, they thoughtfully describe the complex experience of life in these once prosperous coal towns—that boomed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Little Cities

Little Cities is a visual meditation on the ways cultural forces shape our relationship to the landscape. It examines how both Indigenous peoples and descendants of settler colonialists inhabited and utilized the land around them.

The images depict the man-altered landscape within the rural Appalachian communities of Southeast Ohio, a microcosm of unsettled issues that transcend the region and permeate the nation’s psyche. This study observes the correlation between the physical landscape and collective memory.

The infrastructure has its own vernacular, and the images depict the heavy hand over the land, alluding to the fading American Dream and the ongoing “Native Nightmare.” In my Appalachian home, the region is engulfed in poverty. Amid the deteriorating architecture of the coal boom, despite colonial efforts of erasure, evidence of ancient Indigenous existence dots the landscape like fading fossils–unseen and unheralded.

Sacred Indian burial mounds sit between suburban tract homes, webbed powerlines, scrawled graffiti, acid mine drainage, banal Midwestern commerce, parking lots and one-room post offices, closing the gap between past hopes and present regrets. Within these spaces, the physical and psychological merge.

Centuries have elapsed since the last Indigenous tribe was relocated from this region, and decades have passed since the valuable resources deep in the earth were extracted. Today we reflect, reconcile, and strive to repair wounds to both the land and its people. These observations are born from the desire to understand who we were, who we are, and who we may become.

Daniel George: We’ll start off by getting personal. Regarding your photographic interests, what compels you to focus on authentically depicting aspects of place, community, and cultural identity?

Rich-Joseph Facun: I don’t see my photographic interests as a separate entity from my own self-interest. When I reflect on topics I have pursued as a photographer they have more often than not been nurtured by basic existential thoughts. This notion has motivated me to visually dissect/interpret place, community, and cultural identity. Moreover, I find solace and wisdom in how these elements shape and influence myself, the individual, and society.

I attribute these feelings from my transient childhood and personal cultural experiences. My father was an immigrant who served in the US military for over two decades requiring us to move to a new port every three to four years. Additionally, being of mixed heritage – my mother is Otomi, and my father is Pinoy – often left me seeking to define my own identity, craving a sense of belonginess and clarity.

DG: You have been all over the world in your work as a photojournalist, but what brought you to southeast Ohio?

RJF: In 2014 I was a full-time staffer for a metro newspaper in Virginia. I had put 15 years or so into the industry and no matter how positive I tried to be; the writing was on the wall – print journalism was on the decline and in dire straits. I knew I needed to diversify and find a new source of generating revenue to care for my wife and children. Not to mention, I had been uprooting my family every two years for 15 years – always moving onto the next job prospect. I could see it was taking a toll on my two youngest kids. My wife and I wanted a lifestyle change for all of us. This meant, rural living, small town life, and a community that embraced diversity and inclusion. Long story short, I pivoted and took a job in communications and marketing for the medical college at OHIO University in Athens. We moved here in 2015, settled in, bought some land, built a network of friends, and haven’t looked back.

DG: What effect has your journalistic work had on your approach to photographing this region in this way?

RJF: Having been trained and educated as a photographer and documentarian under the theory and ethics of journalism influences me to make work that is an honest representation of what I see. This ethos applies to any region I am documenting.

However, philosophically I’ve always questioned one’s ability to make work that is objective or absolute. The concept that objectivity exists and can be applied to the way in which one sees, processes, and captures the world within in a frame seems optimistic at best, yet delusional.

Those points aside, one of the more valuable assets I’ve carried with me from my time as a journalist is the ability to weave concepts and abstract thoughts into a coherent visual narrative.

DG: I’m curious about your research and creative process. With these series specifically, did you begin by delving into the history of the Little Cities of Black Diamonds before setting out to make photographs? Or did you start with visual exploration—eventually being led to the stories that you’re sharing?

RJF: My initial awareness of the Appalachian region referred to by the locals as the Little Cites of Black Diamonds was casually introduced to me by a friend. I took a mental note and stored it away. At the time, I was on a hiatus from photography but thought it might make for an interesting story.

Two years later I began seeing images again. I forced myself to pick up my camera and made the first image for what would eventually become Black Diamonds. At the initial start I had no defined intent of where that would take me. I simply needed to satisfy a craving to make new work and quench my curiosity of the unknown. As the series developed, I began to research local history, seek out anthropological and sociological based writings about Appalachia as a whole, and dig into the archives at the historical center here in Ohio. At this point, both image making and research began to run parallel to each other.

While working on Black Diamonds the man-altered landscape within the rural Appalachian communities began to pique my interest. Making images of these observations, I experienced a new connectivity to my Indigenous heritage. The ancient Indian burial mounds that share spaces with the postindustrial decay of the former coal mining boomtowns where I now live seem to speak to me.

Although I found these visual notations did not fit into the narrative of Black Diamonds, I continued making them. I had an inclination that they may lead to something more than a passing thought.

A year or so later I took a deeper dive into exploring the earthworks and sacred burial mounds of the ancient Indigenous Adena and Hopewell cultures present in my community. Part of this endeavor led me to researching the history and plight of the Indigenous tribes of the region.

Eventually, the work led to the publication of Little Cities which is a visual exploration of how both Indigenous peoples and descendants of settler colonialists inhabited and utilized the land around them.

Through both bodies of work, I submitted to the creative process, allowing the images to lead the way and show me where the story was going. It was very much an intuitive and liberating practice.

DG: In Black Diamond’s Unspoken Psalm, you write that Appalachia “is fraught with mystery and mischaracterization…” and that your images “strive for understanding…”. What sort of new or more accurate comprehension do you feel these photographs provide?

RJF: In an effort to not beat a dead horse, I think CNN writer Jacqui Palumbo articulated this point best when she wrote:

“Black Diamonds” is also a unique series in the photo world. Countless White photographers have documented communities of color for major publications, photo books, photo awards and personal projects, but a BIPOC (Black, indigenous and people of color) photographer setting out with his camera to explore a predominantly White area is much rarer.”

Some might question how the images would be any different if they were made by a white male or someone not of the BIPOC community? To that I ask, “How would the history of the US differ if it had been written and documented by a person of Indigenous lineage or a descendant of a slave?”

DG: You also ask (regarding the broader concept of community as it relates to your image-making) “Am I accepted in this community? Am I safe here?” I get a sense that these questions were on your mind while working on Black Diamonds, and as you were interacting and photographing locals. Despite this seeming unsureness, your portraits feel extremely sympathetic—toward those with whom your acceptance was unknown. Would you share the significance of your embracing this sort of compassionate way of seeing?

RJF: Being at peace within has been a challenge for me throughout my life and is a trait I have strived to improve upon into my adulthood. As I’ve aged, I’ve thankfully become less confrontational and short-tempered. With this personal progression and development my compassion for others has grown.

Additionally, growing up brown in Mississippi and Virginia while being exposed to racism and prejudice or hearing stories from my parents of times when inequality ruled and justice was not a commodity afforded to them, how can I not be sympathetic to others? Having personally experienced the pain of exclusion, how can I not be inclusive? When I’m confronted with another’s suffering how can I not feel motivated to relieve that suffering? I’d like to think that any compassion you see in my images derive from the insight harvested from my own personal experiences.

Let’s end it with karma, also known as the law of cause and effect, stating that whatever thoughts or energy you put out, you get back—good or bad. I think this reasoning holds true when one is engaged in the act of photography, specifically when making portraits of someone on the streets. There is a collaboration happening there, an ebb and flow, a silent communion. Perhaps we’re witnessing the effects of karma in a photograph?

DG: While both books are about people and place, Black Diamonds seems to overtly concern itself with the region’s current inhabitants and their goings-on (through portraiture and photographs in their spaces). On the other hand, Little Cities implies more about human activity by taking a step back and considering locale (with few actual people found in the photos). Could you talk about this difference of approach?

RJF: I felt that the goal of communicating the effects of capitalism, diaspora of Indigenous people, and the presence of settler colonization might be best told from taking on a topographic aesthetic. With Little Cities, the nuances of the man-altered landscape are intended to carry this narrative. Even without people in the images, the hope is that one can sense they are looking at a portrait of humanity. Yes, the photographs were made in Appalachia, yet the visual messaging was intended to supersede the locale.

DG: In both books, you begin with a short poem. Tell us more about your choice to lyrically prime your photographs.

RJF: The poems at the start of Black Diamonds and Little Cities offer a prime for the viewer – serving as a navigational tool of the forthcoming pages without concisely defining the intent of the series. In a sense it functions as a movie trailer using poetry, verse, impressions, and notions to hint at the underlying intent of the work.

DG: I am interested in the way that your photographs in Little Cities allude those larger “cultural forces” that have shaped the landscape of this part of the country—from signs of indigenous erasure to dilapidated buildings. All related to the rise and fall of the coal industry. Would you further elaborate on your drawing parallels between the “fading American Dream and the ongoing ‘Native Nightmare’?”

RJF: The concept of the “American Dream,” is often highly heralded by patriots of this country. However, historically, under the guise of capitalism and religion, settler colonialists have enacted the cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples. Our lands have been stripped from us, our cultures misappropriated, our languages demolished, and our heritage denied. These cultural forces have attempted to erase us from their history. Systematic racism is at work here.

The “American Dream,” is not inclusive of Indigenous people, in fact it is quite the opposite – hence the “Native Nightmare.” The ideal that every citizen of the United States should have an equal opportunity to achieve success and prosperity through hard work, determination, and initiative does not apply to the Indigenous existential experience.

DG: The final image(s) in Little Cities depict a front/back view of a postcard of Famous Indian Mound, Mound Cemetery, Marietta, OH. There is so much to unpack here—from the American flag at the mound’s pinnacle and it being described “as perfect today as it was when discovered by General Rufus Putnam’s little band”, to Gertrude’s suggestion that Sara’s kids could “play Indian” there. What led you to include this at the end of the edit?

RJF: I’m deeply pleased to find that the inclusion of this postcard resonated with you and carried the intent/insight I was striving to achieve. One point being to create a philosophical and disruptive break among the sequence of the work. Within Little Cities, unlike Black Diamonds, I purposely excluded an index and minimalized any explanatory text. This decision was an effort to encourage readers to dive deeper into the messaging of the work, to discover and collect the clues peppered into the monograph through items such as the poem at the opening of the book and the postcard near the closure – the cyclical placement are points of navigation and interpretations. There are some images within Little Cities that are intended to function in a similar manner. Keep looking, you’ll find them eventually. The work is a very slow burn, a whisper; if you’re not listening closely, you might not hear what is being spoken.

DG: At the end of your artist statement you write, “These observations are born from the desire to understand who we were, who we are, and who we may become.” After having created this work, would you share your personal insights on the topic? What understanding do you have now that has developed from the outset?

RJF: Personally, it inspires me to continue to seek out knowledge about my own heritage. My mother is Otomi – an indigenous people of Mexico. Unfortunately, much of our family history and Native culture has been lost. Once my grandfather immigrated to the US he rarely spoke about our family lineage. His goal was to be “American.” It was a much different time in the States, assimilation was key to survival.

On another level, I’ve learned about the tribes who lived and prospered in the region I now call home. Southeastern Ohio was once a confluence of some 40 tribes that included the Mingo, Erie, Wyandot, Miami, and Lenape people. Eventually it became the traditional homelands of the Shawnee and Osage nations.

As a current proprietor of acreage and a modest home in rural Appalachia Ohio I now hold stewardship of the land where these tribes coexisted. There are sacred Indian Mounds less than a mile from my homestead. With that perspective I have continued to be mindful of how I tend to and nurture the environment in which I reside. To be clear, I do not prescribe to the concept that I “own,” the land, this idea that I “purchased,” it is quite an abstract concept. I often contemplate how anyone “owns,” part of the earth.

Today, I look within, I work to keep myself in check. I ask who I am, who I want to be, and how the smallest of my decisions and actions can influence or change who I become, who my children become.

Overall, my understanding of my responsibility to the land, to myself, to others, to my community, has developed and matured from the outset of the work. I hope this continues.

Black Diamonds

UNSPOKEN PSALM

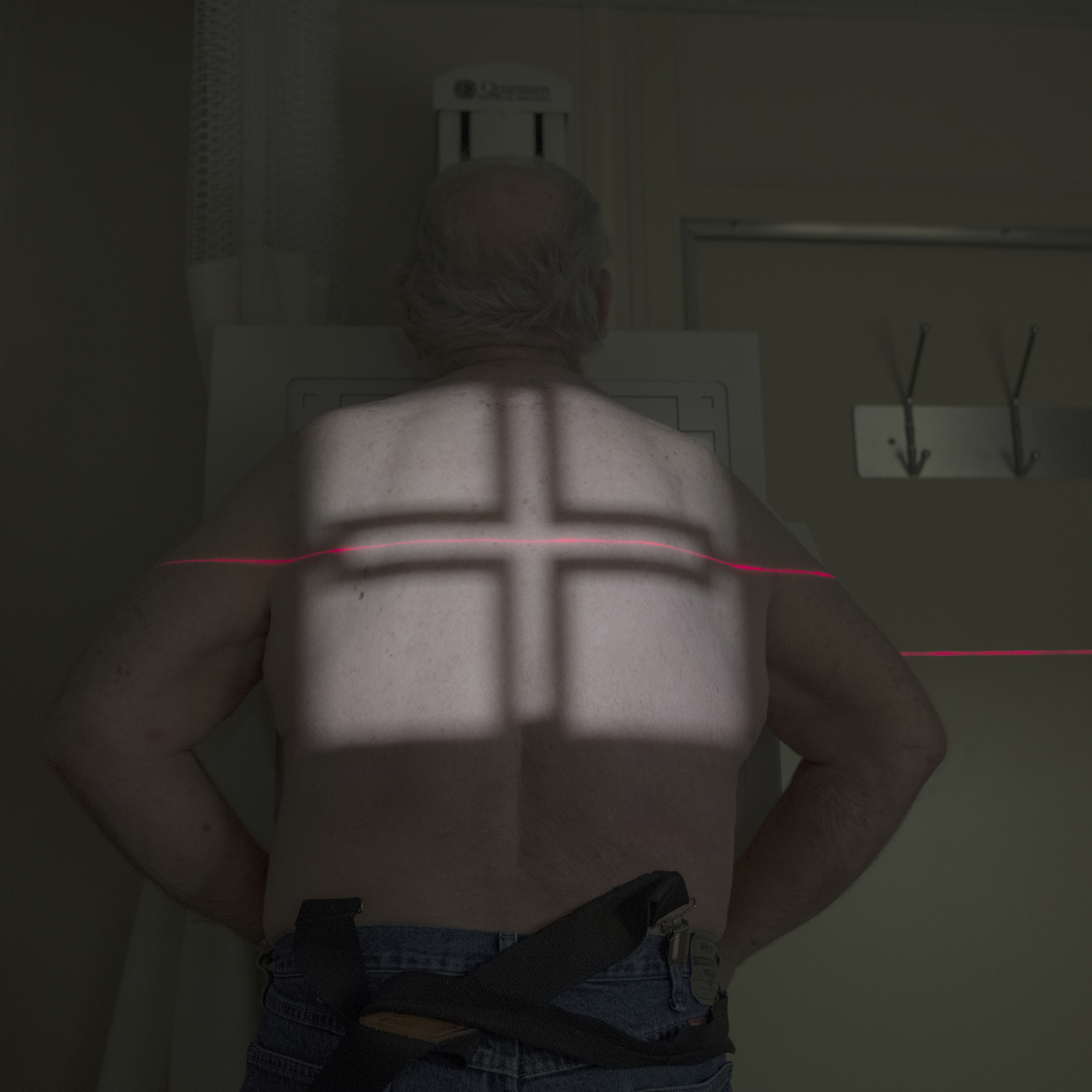

Black Diamonds is a personal endeavor, an effort to connect with and understand the region I now call home. As a person of color, I define my community based on personal experience, which diverges from the stereotypes of race, religion, gender, and politics that can be attached to the area by outsiders. When violence across the nation is aimed at specific groups of people, my images ask implicitly: Am I accepted in this community? Am I safe here?

It is also a visual narration hinting at life as it once was, sharing the hyper-realism of what it is today and the uncertainty of what it is to become in a post-coal era.

These communities, pieces of a whole, are the former coal mining boomtowns of bygone days. The era of coal-fired prosperity was short lived, lasting roughly 50 years from 1870‒1920. After draining the mountains of their bounty and the people of their power, the industry moved on— but the heritage remains.

Life in Appalachia is fraught with mystery and mis-characterization; it’s marginalized or otherwise stereotyped as little more than “Trump Country.” Yet, in all my interactions, that name has never once been involved—in this place, the simple needs of day-to-day survival loom larger than the abstract issues of politics.

My work is experiential and a visual exploration of place, community, and cultural identity in a polarized political climate and racially divided era in the United States. The images strive for an understanding of people and place through their daily goings-on.

In the rural isolated foothills, pocked with poverty, these facets of Appalachia coexist with one another. A heritage of hospitality, not hate, is an unspoken psalm.

Rich-Joseph Facun is a photographer of Indigenous Mexican and Filipino descent. His work aims to offer an authentic look into endangered, bygone, and fringe cultures—those transitions in time where places fade but people persist.

The exploration of place, community and cultural identity present themselves as a common denominator in both his life and photographic endeavors.

Before finding “home” in the Appalachian Foothills of southeast Ohio, Facun roamed the globe for 15 years working as a photojournalist. During that time he was sent on assignment to over a dozen countries, and for three of those years he was based in the United Arab Emirates.

His photography has been commissioned by various publications, including NPR, The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, ProPublica, AARP, The Associated Press, Reuters, Vox, Adweek, Education Week, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The FADER, Frank 151, Topic, The Guardian (UK), The National (UAE), Telerama (France), The Globe and Mail (Canada) and Sueddeutsche Zeitung (Germany), among others.

Additionally, Facun’s work has been recognized by Photolucida’s Critical Mass, CNN, Juxtapoz, British Journal of Photography, The Washington Post, Feature Shoot, It’s Nice That, The Image Deconstructed, The Photo Brigade, Looking At Appalachia, and Pictures of the Year International.

In 2021 his first monograph Black Diamonds was released by Fall Line Press. The work is a visual exploration of the former coal mining boom towns of SE Ohio, Appalachia. Subsequently, it was highlighted by Charcoal Book Club as their “Book-Of-The-Month.” Black Diamonds is also part of the permanent collection at the Frederick and Kazuko Harris Fine Arts Library and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art’s Research Library.

Facun’s second monograph Little Cities, was released in Autumn 2022 by Little Oak Press. The work examines how both Indigenous peoples and descendants of settler colonialists inhabited and utilized the land around them.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Philip Toledano: Another EnglandFebruary 24th, 2026

-

Cheryle St. Onge: Calling the Birds HomeFebruary 23rd, 2026

-

Matthew Finley: An Impossibly Normal LifeFebruary 22nd, 2026

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026