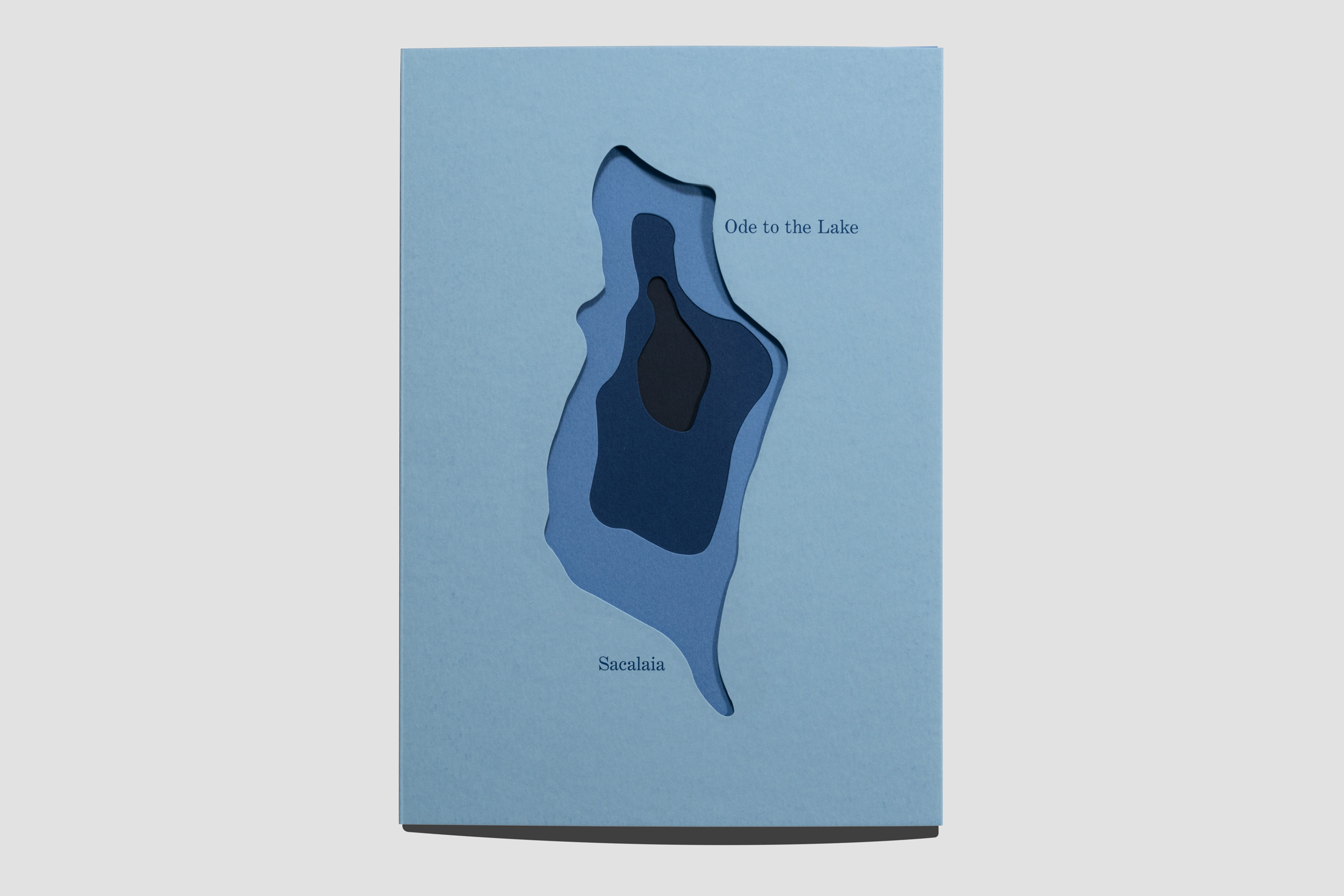

C Fodoreanu: Ode to the Lake Sacalaia

When one imagines a lake, we often think of a calm, still body of water. Perhaps the sun is just beginning to rise over the treetops and a lone crane stands at the waters edge. This lake represents peace, a feeling of comfort. This lake is quite different from Lake Sacalaia. Ode to the Lake Sacalaia, shows us a lake of uncertainty. A lake full of all the unknowns there are in our world. There is a sense of discovery yet one must be careful not to dive to deep.

In his latest monograph, photographer C Fodoreanu explores the ideas of potential and the effects of ones soul in connection to the depths of water. Oscillating between black and white images, text, and full bleed color images, Fodoreanu examines the dichotomy between the properties of Lake Sacalaia and of the lost souls who have been left to the waves.

C Fodoreanu was born into a family with a long tradition of icon painting in Transylvania, Romania. He started painting before inherently transitioning to using lens-based modalities to create his art, from photography and collages, to installations and videos, and creative writing (poems). His work pursues a poetry of light, and explores the human body as a metaphor for how humans relate to the surrounding nature, intimacy, personal boundaries, play, fragility of life, fleetingness of time, faith and divine intervention.

C Fodoreanu holds a BA in Philosophy from UC San Diego, an MD from Harvard Medical School, and is pursuing a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) from School of Visual Arts in New York. As a physician who studied philosophy, he developed an intimate knowledge of the human anatomy and psyche, and a keen psycho-social acumen. This affords him a unique position as an artist to relate, transcend, and personalize his understandings of humans and human nature into layered visual works. He is the author of three poetry books (Romanian), and his visual work belongs to private collections throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia.

Follow C Fodoreanu on Instagram: @cfodoreanu

The book is inspired by an old folktale about a small Roman village flooded by water after the collapse of an underneath salt mine about two thousand years ago. Lake Sacalaia formed as the deepest freshwater natural lake in Transylvania. The story says that when the lake water is clear enough, one can see the tip of the basilica, the highest point of the flooded village. Many have tried to dive in to reach the old village, majority to never return. During his childhood, Fodoreanu took multiple trips in rowboats over the lake in the search for the old basilica, and often wondered about the lost underwater divers.

In his pediatric practice as a medical doctor Fodoreanu sees children beginning their life with great ideals and goals only to fail to achieve those due to a multitude of reasons (social, cultural, economic, and such.) As they grow older, children seem to lose themselves in becoming adults, seem to forget and dilute who they truly are or wish to be. Life starts happening fast, and most of the time they get caught in the circle and start running barefoot. They are forced to change into a shadow of what they once have dreamed of becoming. Hardly a handful of them make it to the finish line becoming who they really aspire to be, living their truth.

In the analogy with the lake, the divers who don’t come out are the lost souls, the unfulfilled potentials. They should be the ones reaching for the highest point – the basilica – only to drown instead. An alternative meaning for the divers is proposed in this book, in which their loss becomes the drops and grains adding to the lake they drown in, creating the foundation for the few able to sail over and achieve their goals.

To purchase Ode to the Lake Sacalaia, click here.

Kassandra Eller: How did your photographic journey start?

C Fodoreanu: I distinctly remember a bright eyed day holding in my hands a worn old Leica camera. Fragile and small, almost slipping away from my gloves. A fresh morning of winter in the Transylvanian mountains, large falling snowflakes and blistering cold. Unbeknownst to me, manually rolling the film to the next frame was not required, and no immediate visible results enforced that. Peaks were falling on each other, trees and birds beating with a same heartbeat, in my frames. Months later I learned how powerful this act was – how unavoidable, direct, and blind, the capturing of light and shadows, the vivid memory forming in my young mind. The end results, the prints later revealed, were not mine but instead part of me in a strange way. They were my story, splits fixed of time, but also themselves, unconstrained, free. And ever since then I kept looking for that feeling again, muddled in a childhood lost, lingering for the intensity of that simple click, a simple act creating that echo of time, with or without gloves.

KE: You also work as a physician in addition to being a photographer. How does your job as a physician play a part in your artistic practice?

CF: My medical practice informs my art practice, and in return, my art practice informs my medical practice. It is a two fold balancing process, revealing and self healing. My work is inspired by the human feelings, play, beliefs, experiences and perceptions, with their avalanche of ripples, deciphering for beauty or not, entropy or not, confessing insights granted to me in the pursuit of what is human – mortal, fragile, loving. Both practices involve human bodies from their entirety to their compulsory organs, from macro to micro perspectives and universes, aligning towards detangling the mysteries of the organic body and intangible mind, as entrenched in the surrounding nature of our world. And so this defines my visual pursuit – ethereal but classical, withdrawn but tender, deliberate but mysterious, soft but caring, abstract but figurative.

KE: How did the idea for this monograph come about? You state that as a child you used to take a rowboat out onto Lake Sacalaia. Is that where this project really began for you?

CF: This monograph took shape during the pandemic. The initial images created during childhood were done with no pre-thoughts, no plans. The capturings were part of a play, a wonder over the mystery of the lake, rowboating over, fearfully hoping to get a peak of the unknown, maybe capturing a shape or form easily missed by our children’s eyes. Something to stain in time for later, calculated and intense exploring. The negatives were then lost in a dusty old paper box, victims of shape shifting times, until the pandemic, with its plenty of hours to spare in the vicinity of self, gave change to re-discovering, reconnecting to what holds me true to myself. As I relived the emotions of those boat trips, the tales of the lost divers searching for the depths of the lake, and the innocence of looking ahead, a connection appeared in my mind with the stories I witnessed daily at work. Learning of children blissfully looking ahead to a future of unknown, planning adventures and explorations, in the search of self, and the search for their place in the world, only to slowly fade away, beared down by the heaviness of an unforgiven life. Additional images created in the years of the pandemic to complete a circle of meaning were added to the pile. Exploring the tension of self-discovery and identity, queer or not, and the in-between states of one’s self-awareness took center stage. Paying homage to younger selves searching for faith and ideals, towards making sense of the loss of potential that I witness in my pediatrics practice, generated into this monograph.

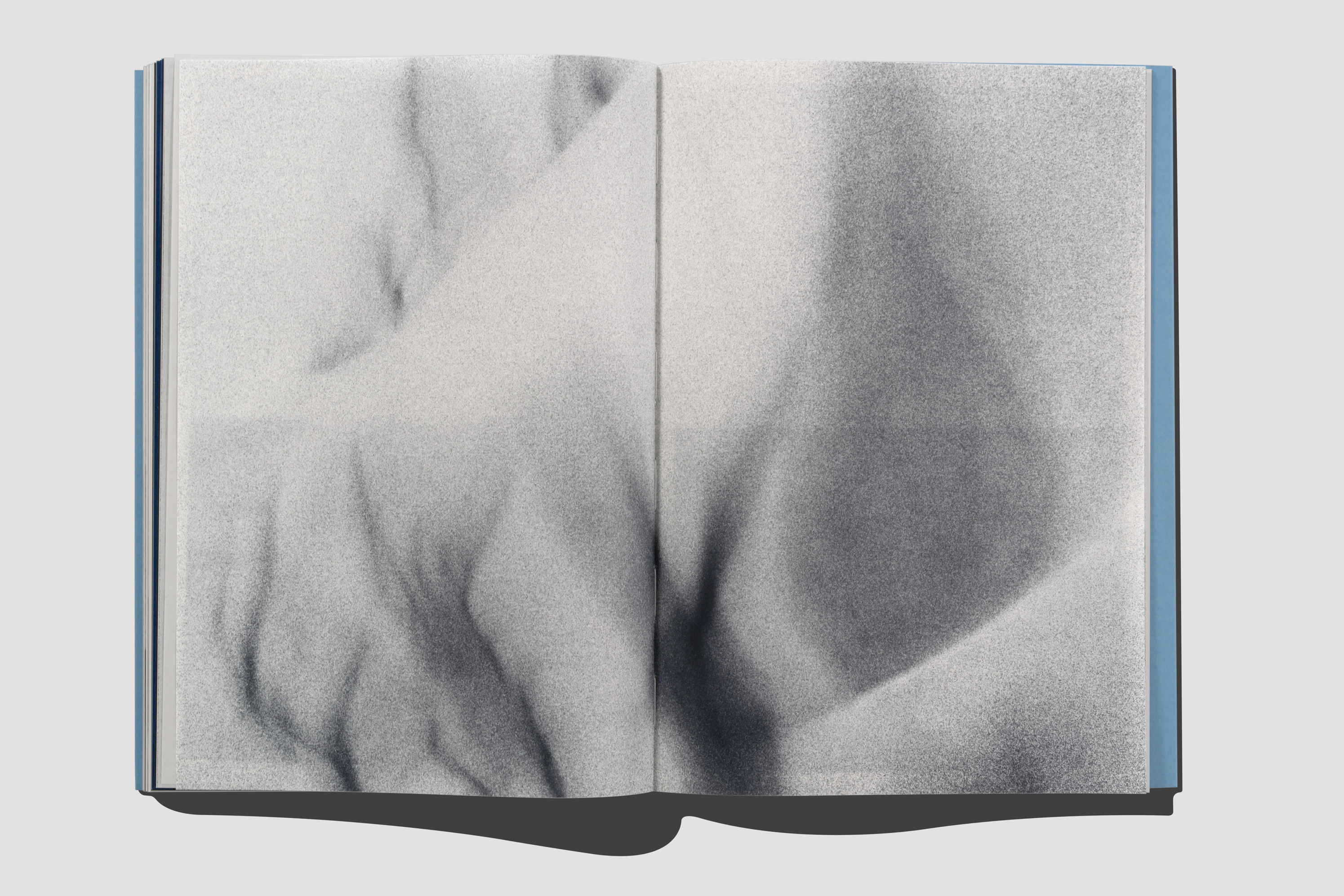

KE: As I began looking through this book I noticed that the pages began to thin. Towards the beginning, a thick cardstock was used but at the end, you used an almost tissue-like paper. I imagine the use of paper in this way is meant to represent the lake. As you flip farther through the book it is as if you are swimming toward the surface. Would you like to elaborate on this choice and the importance it plays in this monograph?

CF: I am so glad you have picked up on this tactile information. That has indeed been the intention. The book uses a haptic approach to represent the changing depths and pressure of water and self-examination, progressively moving toward thinner papers for each of the three sections of the book. The deepest fresh-water lake in Transylvania, Lake Sacalaia formed, legend has it, when a salt mine under a small Roman village caved in about 2000 years ago, leading to the flooding of the village. When the water is clear, it is said, one can still see the spires of the basilica, the highest point of the submerged village. Over the years, many divers have tried to reach the basilica, some of them never to return. The thinning of the paper intends to recreate an experience for the reader, similar to the experience of the submerged people and divers trapped into the depths of the water, transgressing into layered dimensions, strayed in a place with unclear and dissolving coordinates. Additionally, the cover has three die cuts which trace the depth of the water from the lake’s topographic lines, hopefully submerging the reader into a place of childhood wonder as it was for me in exploring this lake.

KE: You have made very deliberate choices both in how you place the image on the page and in the use of both black and white and color imagery. It is intriguing how the only color photos are sectioned together as full-page spreads. Why did you choose to sequence and compose the images on the page in this way?

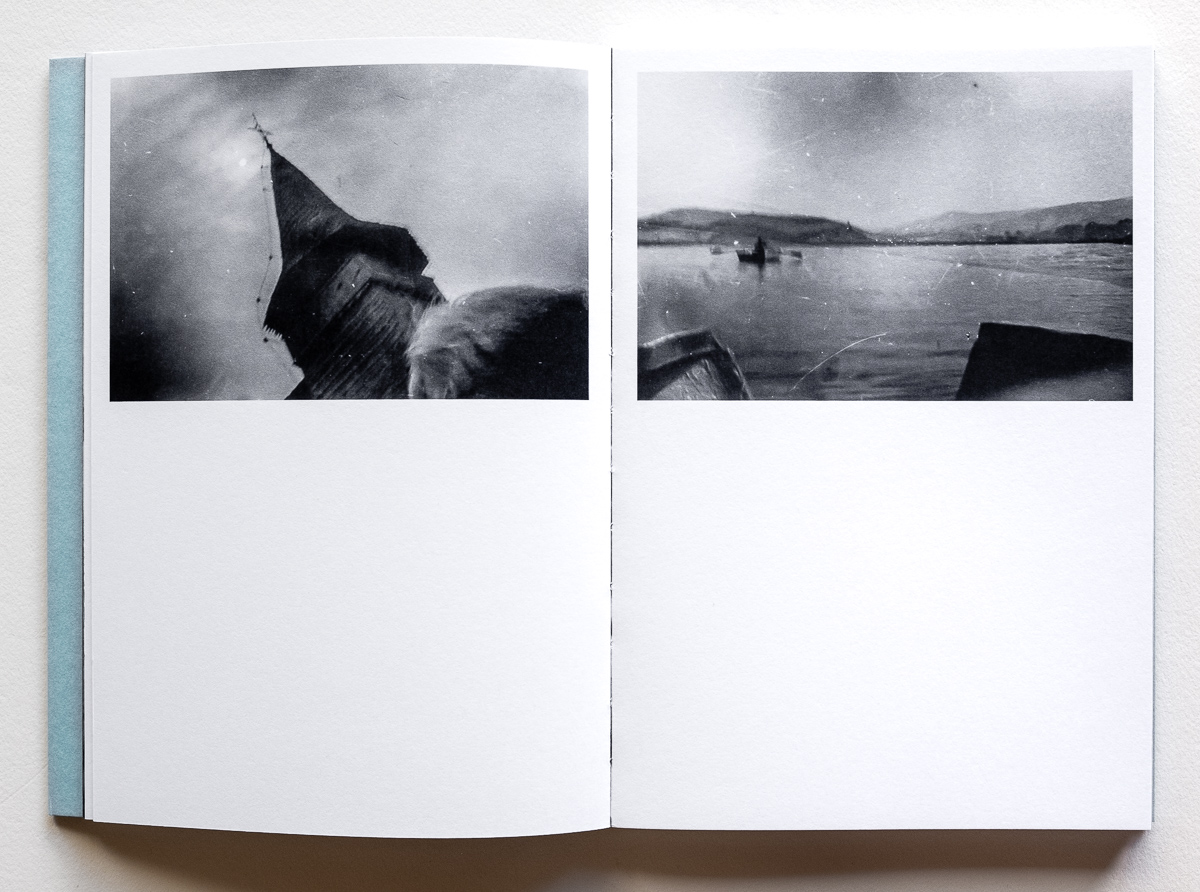

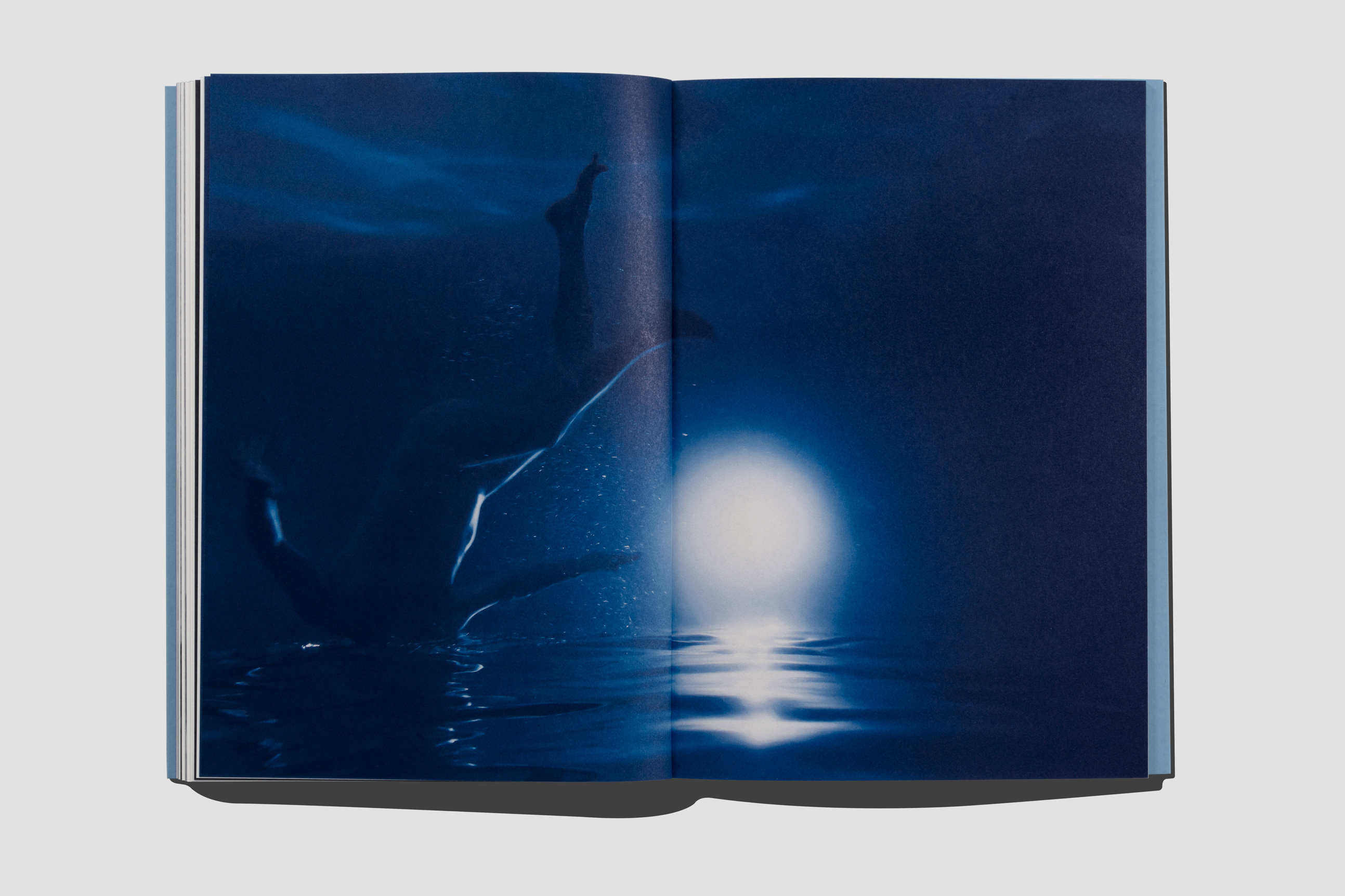

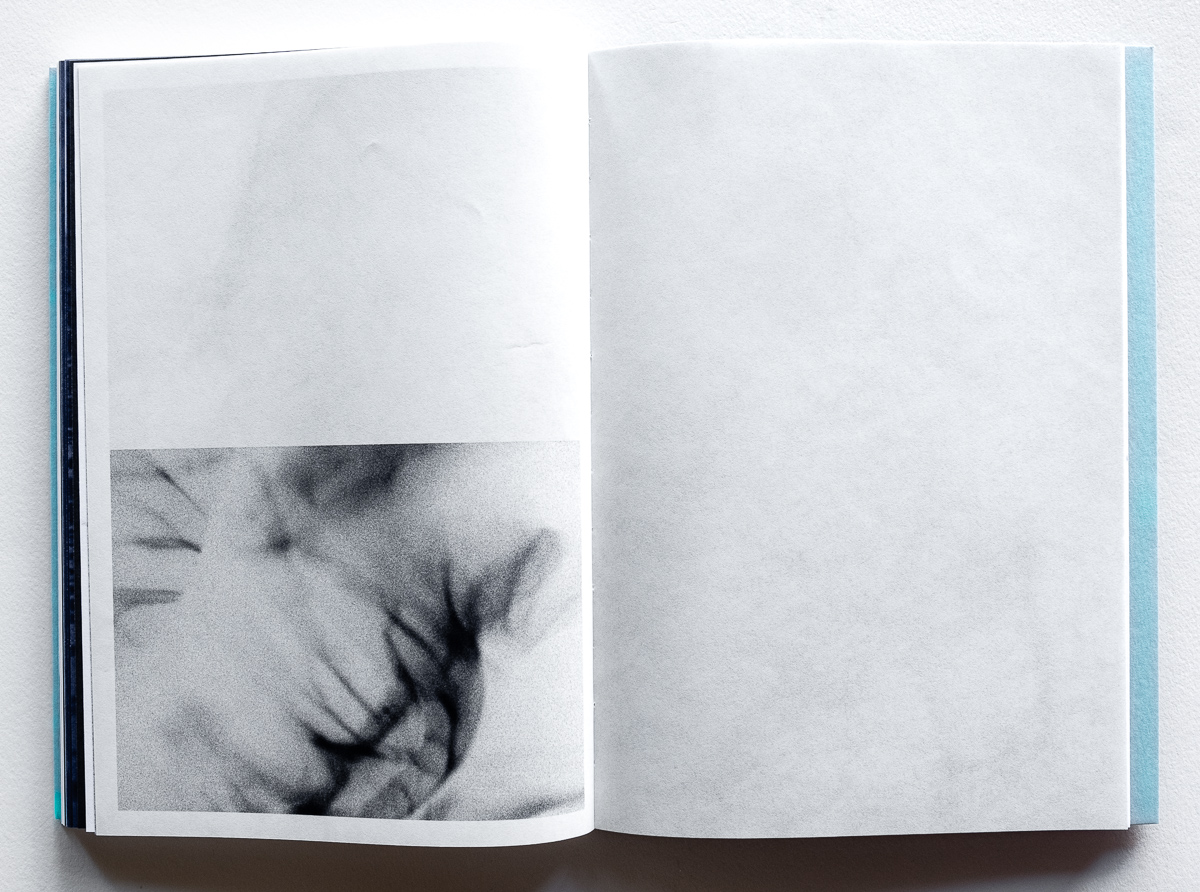

CF: That is a good question indeed. The beginning black and white images are reflecting people and places above and around the water, recollected and placed together from fragmented memories, none of them alone completing a full picture. They aim to rebuild a feeling, deep down buried, formed from innocent fears, beginnings, expectations, hopes, all appearing on clean white pages here and there, corners, ups and middles, building a somewhat frame of reference. Then the colored images are the submerging pictures. Full blown, acts completely assumed – absolutely aware, in plain view. Diving, swimming into the unknown to reach a higher ground. They are volitional, directed, with a purpose – full-page spreads.

KE: In this book, you utilize text in a unique way. Each story acts as a way to section the images, yet provides insight into Lake Sacalaia and its histories. In your opinion why was including this text imperative to this book?

CF: The wonderful essays written by Seph and Shana anchor sections of the book. They give insight into the history of the lake and its legend, and the significance of water in the cultural psyche. These texts are not mandatory readings, but they are present in case the reader is looking for more subcontext, giving additional layers in experiencing the book. I also have a personal poem to accompany and anchor the images in a way between the visual and a state of mind. I probably recommend looking at the images in the book without looking at the texts initially, and then go back and look at the images as anchored by the essays. I found that each reader experiences the book differently, and the poem and essays could function as gateways to the next section of the book. But again, these are only there to substantiate the message of the book for someone inclined to look for that.

KE: Ode to the Lake Sacalaia seems to be a very personal project for you. The way you capture these images creates an intimate bond between the image and the viewer. How did you decide what to photograph? Did you compose these images or capture these moments as they happened?

CF: It is a personal project indeed, and the culmination of about two years of imagining, planning, developing, and fusing together four stages of work. As already mentioned, the initial images of the book were done intuitively, as part of the discovery of self and the lake during childhood. The double, triple exposures, the cut angles, perspectives and frames were all included in this innocent play of the time. The next images, the one suggesting the movement of the swimmers, in the second section of the book, were created in a dark room studio using two light projections showing fragmented bodies under water on a white screen while capturing video of a body in motion in front of them, such creating shadows over shadows and intermingled fragmented body shots. Even though assumed, these images were planned to be randomly created. They are in fact stills of this video, the most successful angles and compositions noticed later on purview. The randomness, the play assumed of the past, the no-need of carefully framing the photos has been kept throughout this process. Same goes for the blue images that were done on location at the lake during my last return just before the pandemic. These were left to the chance of a timer, and the diver jumping in the lake without planning. Additionally, the last images of the book, the ones printed on tissue-like papers, are the fragmented images of underwater swimmers used in the double projections mentioned earlier. Working on all these projects, so intertwined during the years, with previously created images playing a part in the newly exposed ones, and the newly discovered negatives giving voice to lost feelings and wondering of the present, assumed the randomness and the accidental beauty of the past.

KE: In many images we don’t see a full figure, rather we see hints and shadows. Why did you choose to use these figurative actions to represent the human form?

CF: There is something to say about personal space. When present in this space, one only sees bits and shadows of the other. The proximity to the other’s body narrows one’s field of view. The entire body dissolves. The full figure dissipates. At the same time, when situated so close to the other, one’s eyes are usually closed. The intimacy comes from a tactile sensation, from temperature and whispers, from shivers and glee. Closing the eyes also represents an abandonment of fears, unequivocal trust, a leap of faith of some sorts. The visuality of this space has not been explored. As such, I am tending into this dimension hoping to bring a visual intimacy instead. I am keeping my eyes open, still abandoning the fear, still trusting completely, still taking a leap of faith, but wide awake.

KE: In this monograph, you seem to make a comparison of the depths of the water in the lake to the depths of the self, how the deeper one goes, the more entwined one becomes. Would you elaborate on this dichotomy of the water vs. the self?

CF: Water has been so vital for my imagination. I grew up on a lake, spent beautiful presences there, found an inner quiet of self, and planned for the hereafter. And our bodies are made mostly of water. And the earth’s surface is mostly water. The fluidity, the positive reduction factor of all dissolving into liquid, a symbolic mesh of similarities around us, has been so inspiring to me. As the greatest illusion of all, the illusion of separation, dissolves, there seems to be a depthness to our soul searching, down spiraling towards a quarry, a so unachievable, feeble, fleeting, but always there and assured presence. Almost to the core, towards a vital impetus, a primordial drop in all of us.

KE: In the details section of this book, you describe the divers in the lake that don’t come out as lost souls, the unfulfilled potentials. I would love to hear your thoughts on the idea of lost souls and the interaction of these souls within Ode to the Lake Sacalaia.

CF: In my pediatric practice as a medical doctor I see children beginning their life with great ideals and goals only to fail to achieve those due to a multitude of reasons (social, cultural, economic, and such.) As they grow older, children seem to lose themselves in becoming adults, seem to forget and dilute who they truly are or wish to be. Life starts happening fast, and most of the time they get caught in the circle and start running unprepared. They are forced to change into a shadow of what they once have dreamed of becoming. Hardly a handful of them make it to the finish line becoming who they really aspire to be, living their truth, being true selves. In the analogy with the lake, the divers who don’t come out are the lost souls, the unfulfilled potentials. They should be the ones reaching for the highest point – the basilica – only to drown instead. An alternative meaning for the divers is proposed in this book, in which their loss becomes the drops and grains adding to the lake they drown in, creating the foundation for the few able to sail over and achieve their goals.

KE: To conclude I would like to ask what is next for you. Is there anything you are currently working on?

CF: I am currently preparing two upcoming shows for the summer. One in Los Angeles and one in New York. The one in Los Angeles will be at the Ronald Silverman Gallery from 7/24 to 8/30 and will take the images and the ideas from the book even further. The show will be an immersive experience in which the visitors could imagine themselves in and around the lake, with sounds and shadows, water presence all around, video projections, of course photographs, and also sculptural installations. There also will be discussion panels in which pediatricians, artists, scientists, book makers will discuss the themes developed by the book. The show in New York, at the Invisible Dog Gallery from 7/5 to 7/26, will also take on some ideas from the book, but a bit in a different direction. The show will explore the human body as a witness to the passing of time, as a pergament of experiences, a tabula rasa getting written all over it, with dents and the folds of nights and days modify the occupying soul, altering, changing the flesh, whispering, inspiring to an all standing tall resilient stance – as if the presence itself over time is testifying to a prowess despite its vulnerable porous form.

KE: Is there anything I didn’t mention that you would like to add?

CF: Thank you for the opportunity to answer your questions. Lenscratch is such a wonderful platform for photographer artists all over the world. I am so proud to bring my contribution to your readers. Please continue your amazing work!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

Curran Hatleberg: Blood GreenMarch 9th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026