Kim Llerena: American Scrapbook

This week we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Kim Llerena and I discuss American Scrapbook.

Kim Llerena is a photographic artist currently based in Miami, Florida. She holds an MFA in Photographic & Electronic Media from the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and a BA in Journalism from New York University (NYU). She exhibits nationally in addition to serving as full-time faculty at the University of Miami. Her work investigates our constructed relationship to place, particularly our methods of delineating terrain, territory, and private/public space. She is also interested in the various dualities that characterize the photographic medium, including memory & aspiration, translation & description, and art & snapshot.

Llerena is included in the permanent collection of The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. She was a 2022 Miami-Dade Artist Access grantee in 2022, a D.C. Commission on the Arts & Humanities Fellowship Program grantee in 2020, a Flash Forward Competition top 100 winner selected by The Magenta Foundation in 2019, and a CENTER Review Santa Fe 100 photographer in 2019. She has been featured in LensCulture, Fraction Magazine, The Washington Post, and numerous other publications. Recent exhibitions include the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, Louisiana; Photographic Center Northwest, Seattle, Washington; The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; Candela Gallery, Richmond, Virginia; Academy Art Museum, Easton, Maryland; Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington, Arlington, Virginia; 621 Gallery, Tallahassee, Florida; and Photographic Resource Center, Boston, Massachusetts.

American Scrapbook

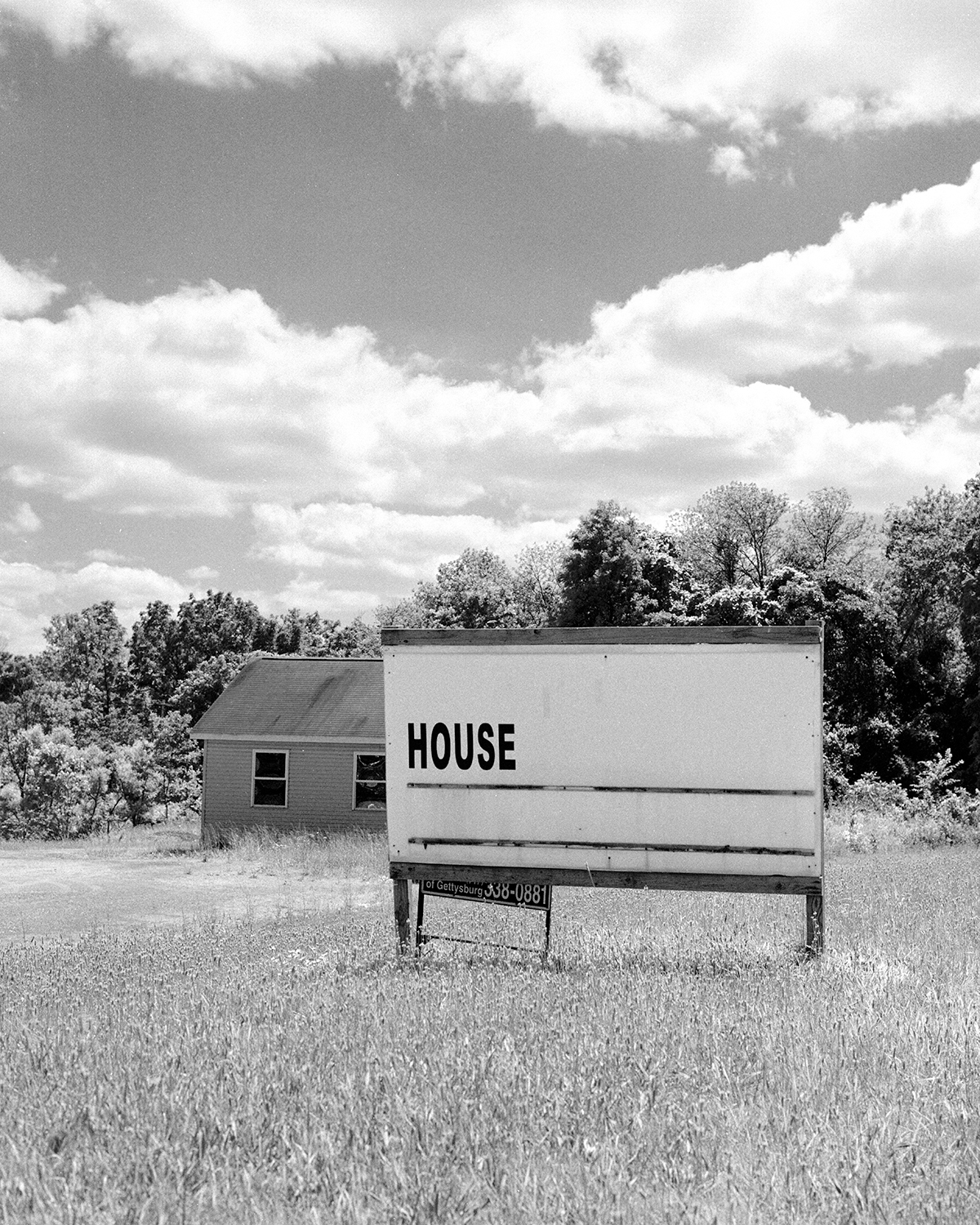

My recent work, “American Scrapbook”, depicts fragments of the American experience: private back yards, public roads, landmarks built or dismantled. Viewed together, relationships between disparate sites and structures emerge, highlighting various systems that direct our collective national consciousness: business, infrastructure, territory, history, politics, religion, entertainment, and more.

Dictated by these invisible forces, the indelible marks of past actions and diverse quests for an American Dream become potent symbols in our visual landscape. The photographs – of walls, gaps, signs, memorials, artifacts, debris – construct a shared language from the physical material of these systems, one that both reflects and forewarns.

In many images there is a sense that something is missing, whether physical or contextual, underscoring the incomplete narratives that photographs and history often tell. Absent also of human figures, it is as if the subjects of these images are waiting for something, suspended in time, suggesting a portrait of our past, present, and future all at once.

Daniel George: What brought about your interest in the “fragments of the American experience” that ultimately led to the formation of this series of images?

Kim Llerena: A central theme in my work for more than a decade has been our constructed relationship to place. I’m interested in the ways we build, mark, and delineate territories and structures to signify our existence somewhere. Some of these actions are mundane, like putting up fences and planting trees in our backyard. Others are unmistakably symbolic of infrastructural letdowns or of the more troubling aspects of American history. Individually, these fragments of the national experience are just that – fragments. When sequenced together, I noticed that they construct a common visual language, one in which the signs, gaps, artifacts, and structures that we leave behind speak volumes in our absence.

DG: I am intrigued by the persistence of, and allusions to the road in this body of work. Although not stated explicitly, I get a sense that this series was part of a road trip, of sorts. At least, it feels that way. What role (if any) did the car play in the creation of American Scrapbook, and in what ways would you say this mode of transportation affected your ways of seeing/experiencing these places?

KL: The car (two cars, really) played a huge role in the creation of this series. Most of the images were made on cross-country road trips that I took with my friend (also an artist). We traveled in her Mini Cooper Clubman and then in my arguably more practical but inherently less cool Toyota Corolla. The number of times I screamed at her to pull over so I could take pictures of something, or veered off course when we were minutes from our hotel…it’s a wonder we made it to any of our destinations.

The reason that’s not discussed explicitly when I write about the work is because, to me, the series is not about my experience on the road. Twentieth century photo history is chock-full of influential road stories motivated by the camera – Robert Frank’s “The Americans”, Lee Friedlander’s “The American Monument”, Stephen Shore’s “American Surfaces” and “Uncommon Places”, Joel Sternfeld’s “American Prospects”, more contemporary projects by Alec Soth, Justine Kurland, Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs…the list is long. (David Campany’s gorgeous photobook “The Open Road”, published by Aperture almost a decade ago, chronicles these projects and likely needs a second volume by now.) Much has been written about these artists’ personal experiences on the road, and looking at some of their work through that lens enhances the experience.

I considered many arrangements of my images when sequencing the final project. When I arranged them chronologically or according to my own travels, the meaning got totally muddled, and that’s because the work wasn’t about me or my route – it was about the visual language of our national landscape and the invisible systems that contribute to it.

DG: And piggybacking on that last question–what do all these symbols of the “visual landscape” imply about the American cultural experience along the road?

KL: Hopefully, in the sequencing, state lines disappear and there is a sense of universality, or at least a collective familiarity. Of course, there’s no singular, definitive American experience. The historical systems that inform these images – systems of business, politics, religion, territory, tourism, etc. – manifest themselves in starkly different ways regionally, but ultimately the connective threads are the most interesting to me. There are representations of Jesus and the Virgin Mary in Connecticut and Texas and Iowa; references to wildfires in New Mexico and droughts in California; visual reminders of a marginalized Native American experience and a long-romanticized era of “cowboys and Indians” across the Southwest. The photographs in this series depict relics of these influences and histories, and they suggest common themes between distant places, but they intentionally stop short of offering a complete narrative.

DG: I appreciate your use of “scrapbook” in the title—suggesting that this is effectively an assemblage of memories/marks/materials that preserve a “national consciousness.” And there is a high degree of nostalgia present, which I think aligns well with your word choice. Would you mind sharing the thought process behind your selection of subject matter and how you feel it relates to memory of place?

KL: The title of this series almost wrote itself. During the editing and sequencing process, it became clear that these images jumped around – from state to state, from theme to theme – much like a personal photo album would. Many of them also recall memories of past events, as you point out. These moments range from positive to mundane to extremely painful. In yards outside people’s homes, for example – very personal yet publicly observable places – I recorded children’s toys, junked furniture, a stone memorial to Michael Jackson, and remnants of a Confederate flag. Nostalgia for a bygone era, as we know, is not always a positive thing.

The memory of place is also present in a shuttered Blockbuster in a small Texas town; a levee near the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans; a section of the border wall that only partially obstructs the view of Mexicali in Mexico from Calexico in the U.S.; and a popular, then defunct, now revitalized hillside theme park called Holy Land U.S.A. that showcases replicas of significant locations from the Bible.

On a lighter note, a very particular kind of national memory is preserved above a First State Bank in the middle of Norton, Kansas; the unassuming “They Also Ran” Gallery is an archive of all the “presidential candidates who were defeated…but not forgotten”. To me, it’s so appropriate and bi-partisan that this gallery exists just 75 miles from the geographic center of the contiguous 48 states.

Some of our memory is individual or domestic, some of it is regional or national. Our collective national consciousness of the present era is informed by the confluence of these past events, all of which are in some way inextricably linked to where they took place.

DG: In your artist statement, you write that these images are a “portrait of our past, present, and future all at once.” How do your photographs function as such?

KL: I’ve been told that many of the images are grim, that they are about futility, failure, or crushed ambitions. Of course, some are. Our country is complicated. Many aspects that define and describe the United States’ past, present, and future – our colonial history, our fraught political divide, our ever-growing wealth gap – are grim. Many of the images in this work are ambivalent about the future. The act of dismantling a Confederate monument or cutting out a Confederate flag – positive. But that huge pedestal is still there, and that flag’s outer edges still cling to its wooden frame; the structures are still in place. The advertising of solar power in California or the massive reconstruction of a floodwall system after Katrina – positive. But California is still ravaged by droughts and wildfires and floods, and the earthen levees that support the new floodwalls in New Orleans are sinking as sea levels rise. In these ways, this work both reflects and predicts, records and forewarns. It hints at moments of hope for the future, but only if we actually reckon with the past.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026