Golnar Adili: a long journey of elimination

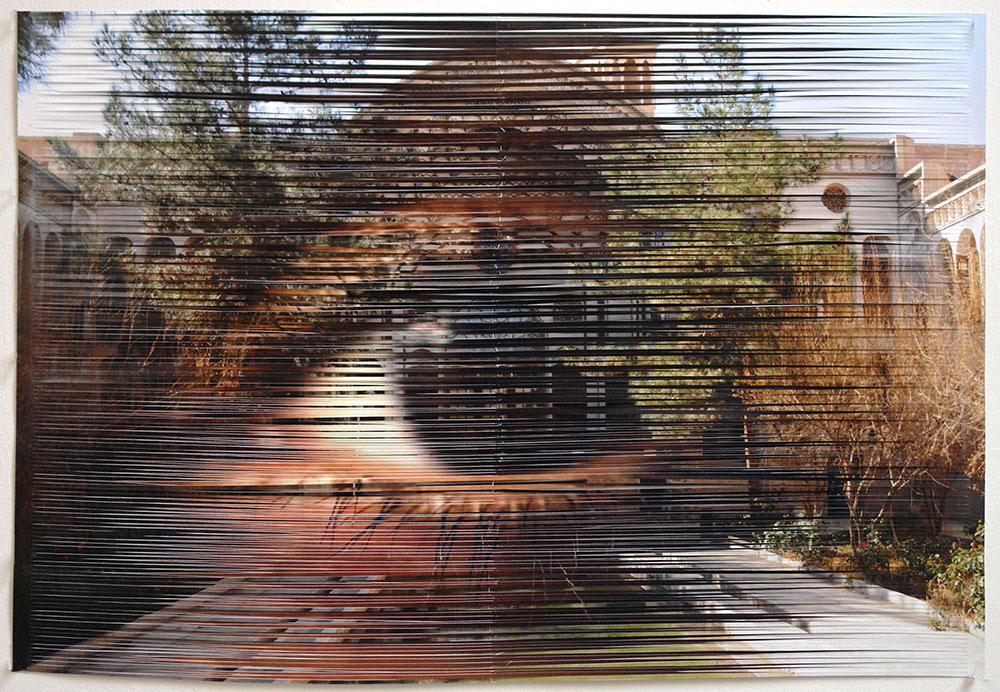

©Golnar Adili, The King-seat Of My Eye Is The Place Of Repose For The Thought of You, 2010, Two photographs cut in 1/8 inch strips and interwoven with a thread 20 x 30 inches

Sometimes I search for new artists on Instagram to find work to show in my classes; that is how I discovered the work of Golnar Adili. I found her story riveting and was intrigued by her way of making art. Her art is layered with meaning, from diasporic identity, to language and place, to family. The American born artist with Iranian parents uses her father’s archive of family photos, documents and letters to construct and deconstruct her own memories, family history and cultural identity. For example, Adili’s Family History Woodblock book looks like a child’s cube puzzle; the blocks, with images on six sides, must be pieced back together for the memories or language to gradually become clear.

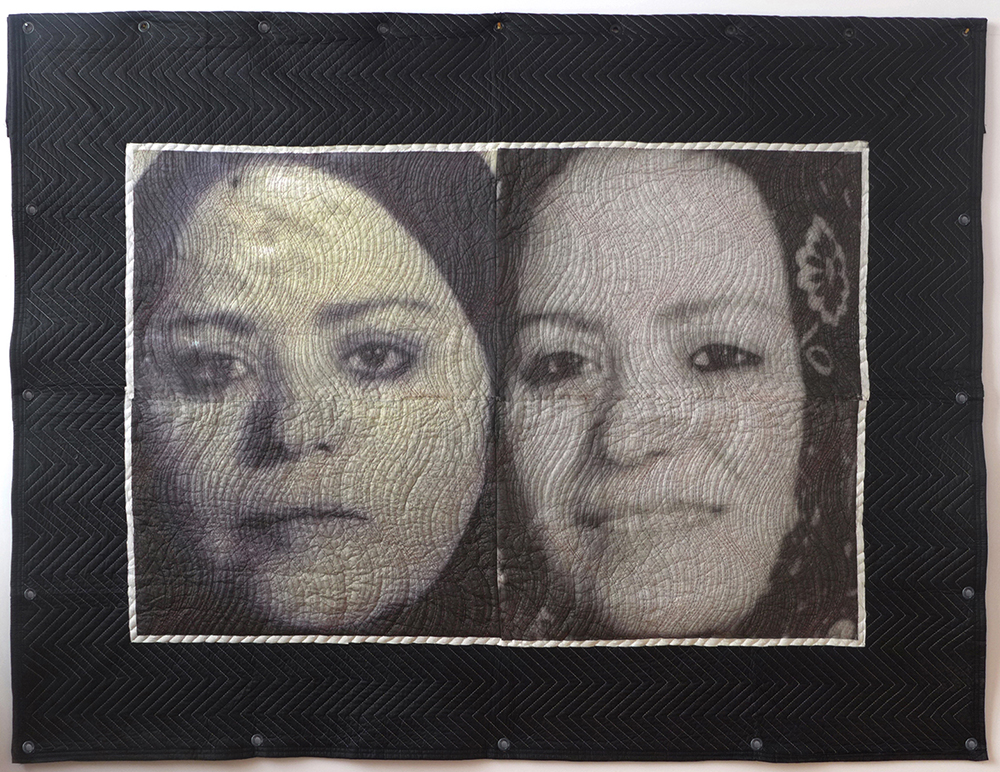

©Golnar Adili, The Organization for Documenting The Mood of The Country (Saazmaane Sabte Ahvaale Keshvar), 2013, Printed Japanese paper, hand-stitched thread, batting, canvas 42 x 60 x 1 inches, The title is a description of the government body responsible for my Iranian identification papers. Tow images of my mother are reproduced from passport photographs; one taken after her return to Iran, the other three years later. The juxtaposition of these photos is a study in contrast. The needlework replicates the security pattern of the interior sheets of the passport.

Golnar Adili is a mixed media artist, educator, and designer with a focus on diasporic identity. She holds a Master’s degree in architecture from the University of Michigan and has attended residencies at the Rockefeller Foundation for the Arts in Bellagio, Italy, The Center for Book Arts, NY, Smack Melton in Brooklyn, the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the MacDowell, Lower East Side Printshop, Women’s Studio Workshop, and Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Workspace among others.

Some of the venues Adili has shown her work include, The Victoria And Albert Museum in London, Cue Art Foundation, NY, and the international Print Center, NY.

Some of the grants she has received include the Pollack-Krasner Foundation grant, the NYFA Fellowship in Printmaking/Drawing/Artists Books. She is a Jameel Prize finalist and Library of Congress, New York Public Library, Rutgers University, Parsons School of Design, Yale University, Harvard University, are a few collections Adili’s Artist Books Live in.

Follow Golnar Adili on Instagram: @golnar.adili

©Golnar Adili, The Organization for Documenting The Mood of The Country (Saazmaane Sabte Ahvaale Keshvar)-Detail 2013

Art is my key to understanding the current underlying my identity and the world through a deconstruction and reconstruction of past traumas. In this ultimately healing process of revisiting and reshaping memory, I have infused my practice with play, inspired by how my child observes and archives the world. Forgetting and relearning both English and Persian multiple times has made language a fascinating reference in my work. Persian poetry, as well as biographical text investigating a landscape of longing, have provided a valuable context for examining language formally. In doing so, I use architecture, book arts, and installation to distort and blur the lines between design, craft, and fine art. -Golnar Adili

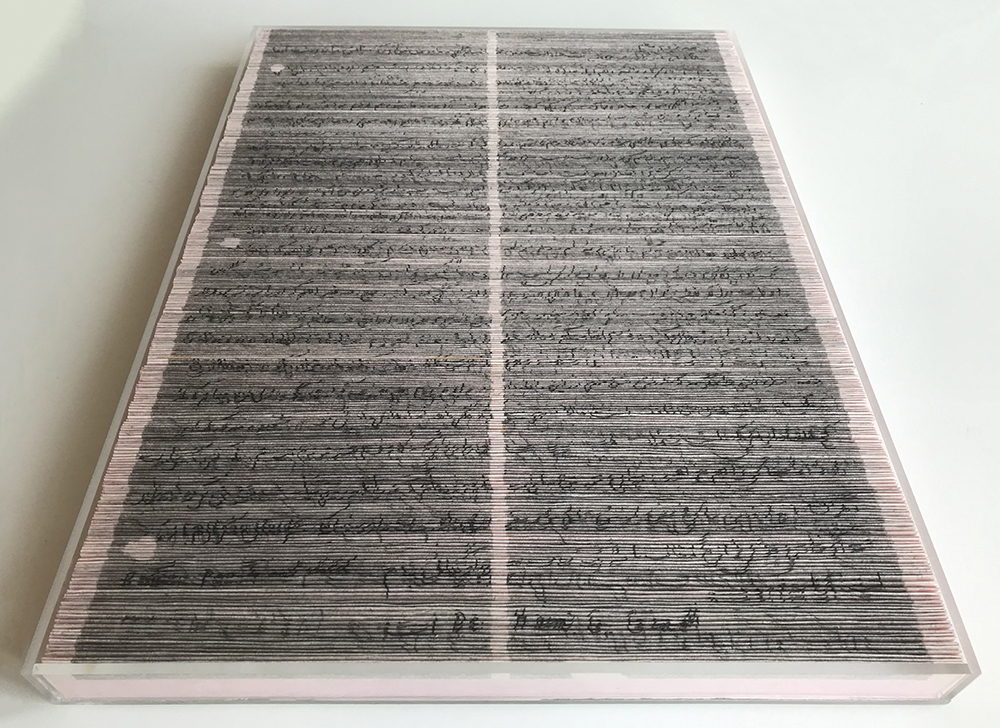

©Golnar Adili, Pink Letter, 2010, 23 enlarge and transferred reproductions of a letter on paper, medical tape, museum board, acrylic case 24 x 18 x 1-1/2 inches

Greg Banks: Tell us about your childhood and moving from Virginia to Iran and then returning again to the United States?

Golnar Adili: When the shah finally left in January 1979, my father left the US and traveled around Iran hoping to build the socialist utopia he had worked so hard toward for so many years as part of student opposition against the Shah in the US- Iranian Student Association Confederation National Union (ISCNU). A few months later, my mother and I moved to Iran to be with my father. I was born in Northern Virginia and I was three years and nine months old in March of 1979 when we moved. I went from the suburban stability of grass-covered lawns, McDonald’s, and our comfortable car taking me from the large supermarket back to our townhouse apartment, into a colorful and chaotic post-revolutionary society where we crashed at different grandparents’ houses with lots of cousins who looked at me like I was clearly not one of them.

As we now know, the revolution quickly radicalized in the direction of a religious dictatorship, forcing my father into hiding. His life was spared the mass executions that destroyed a generation of leftists by his eventual escape on horseback through Kurdistan and then across the Turkish border while pretending to be a woman in labor in the back of a car. My father made it back to the US and a long saga of separation began for my family.

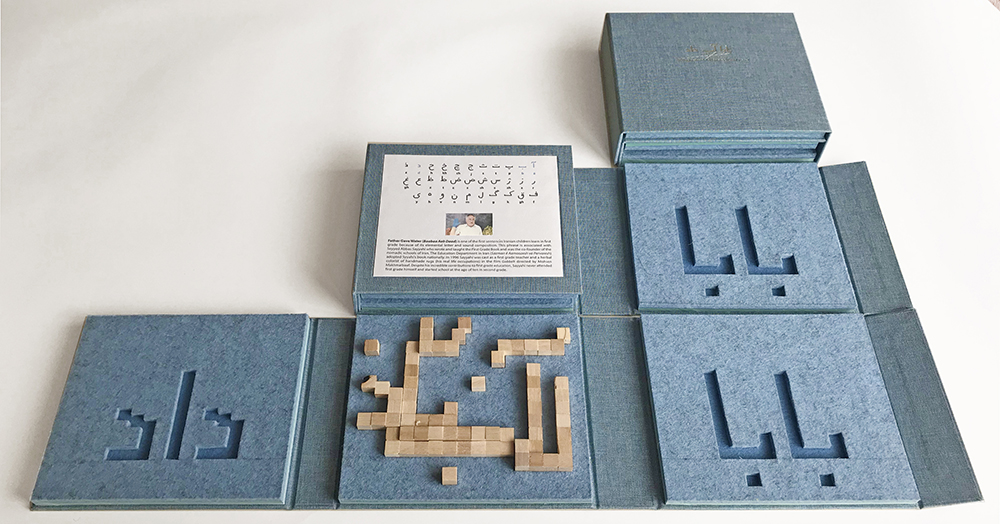

©Golnar Adili, She Feels Your Absence Deeply-Blocks, 2021, Transfer on 1 x 1 inch wooden cubes, book board and cloth 3.25″ x 4.25″ x 1.75” Edition of 50 This book utilizes materials from my archive of letters, photos and printed matter once owned by my father. The collection spans from 1979, when my family migrated back to Iran from the US, and continues through 1981, when my father escaped Iran for fear of persecution due to his activism. Inspired by children’s puzzle books, images are printed on six-sided cubes allowing the viewer to obscure, reveal, mix, and match the intimate artifacts from my collection. The blocks are housed inside a portfolio box that opens flat and carries the print of the airplane ticket used in the final leg of my father’s long journey from Iran. When the box is closed the airplane hugs the blocks, keeping the events inside until they unravel again to tell a visual story of how a family was affected by larger political shifts.

GB: What led to you becoming an artist?

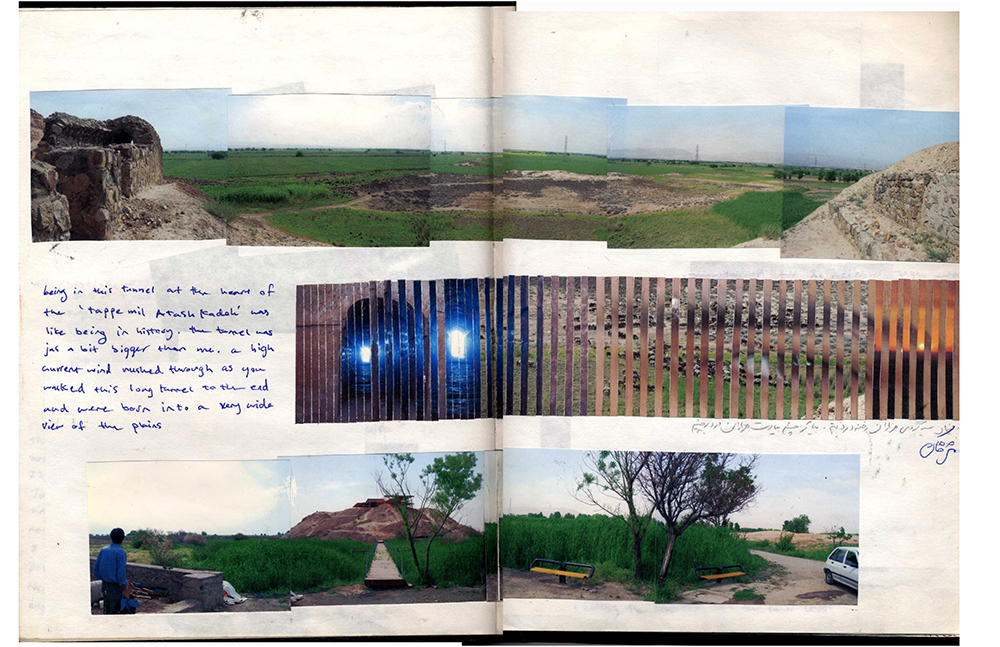

GA: My becoming and artist was a long journey of elimination. I never thought being an artist was an option for cultural and practical reasons-many immigrant children and families are familiar with this. I really wanted to lift the pain of others by becoming a doctor, which I almost pursued and even got into medical school and decided against it at the last minute. I decided that architecture was a good in-between, where art and science met. It didn’t help that I was good at many things and loved learning and challenging myself. I eventually settle on getting a master’s in architecture, which was an invaluable experience, however working in the field was miserable. At 30 I received a travel grant from my graduate school, University of Michigan. This grant was available to apply to for graduates 30 years old or younger and I received it the last year I qualified. I proposed to look at the contrast between inside and outside spaces of Tehran which led me to hang out with a group of photographers and taking a lot of photos from these spaces and fragmenting them to reconstruct them. These collages in my sketchbook were my first attempts in finding my artistic language. I developed my language through artist residencies and fellowships for over ten years instead of going back to school. This was my personal MFA. Some of the first feelings I wanted to convey and process through art was a heaviness I felt in my chest. This led me to look at my own biography and Persian poetry for the longing aspect which I resonated with so closely.

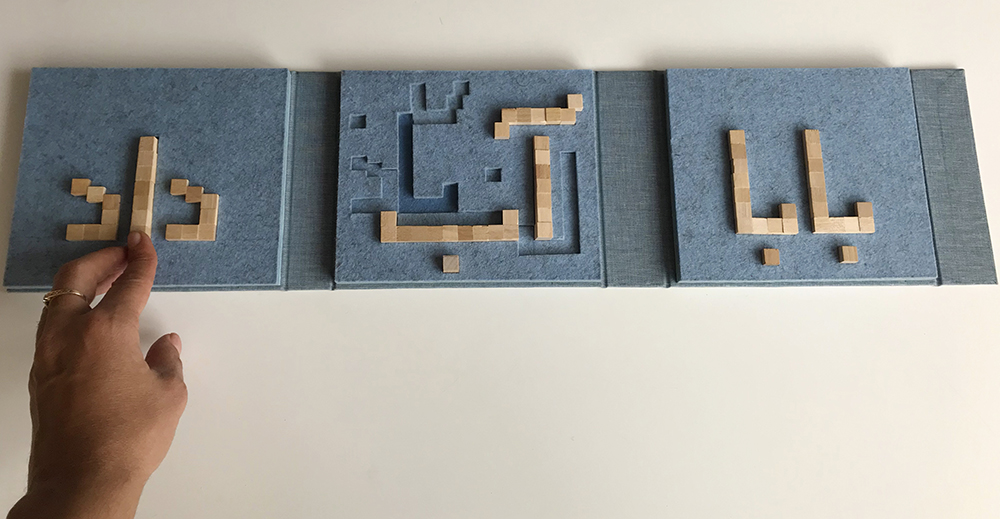

©Golnar Adili, Baabaa Aab Daad (Father Gave Water), 2020, Wood, felt, board and cloth 5 x 7 x 1-1/2 inches (closed)بابا آب داد (Baabaa Aaab Daad)- Father Gave Water is an homage to language and tactility inspired by my toddler’s wood blocks and my love for the Persian language. This phrase, Baabaa Aab Daad made of wood block modules is translated to “Father Gave Water” which is the first sentence first graders learn in Iran. The reason for this is that it has very basic sound and lettering using the A, B, and D (the first letters in the Persian alphabet is similar to the English ones, both being an Indo-European language). Additionally, I have embedded in this book a small history of a wonderful man who further developed the first-grade book and co-founded the nomadic schools in Iran. I decided to entangle him in the book since my research on the phrase “Baabaa Aaab Daad” brought him to the foreground.

GB: How do you think your parents activism effect how you make art?

GA: Their activism meant a life of battling different power structures, first was the Shah of Iran, then its violent aftermath, the Islamic Republic’s hijack of the revolution and a country-wide suppression and execution of the left or any other opposition, and ultimately US imperialism which supported the Shah as a dictator, and then later did not grant my mother a visa back to the US so our family could unite. This is the story of belonging to a third world Marxist family. My whole life was shaped because of this entanglement. It left a big longing and a darkness inside which I am still processing. It is a sort of a generator of art, however, it takes an emotional toll as well.

© Golnar Adili, Baabaa Aab Daad (Father Gave Water)-Detail, 2020 Wood, felt, board and cloth 5 x 24 x 1-1/2 inches (open)

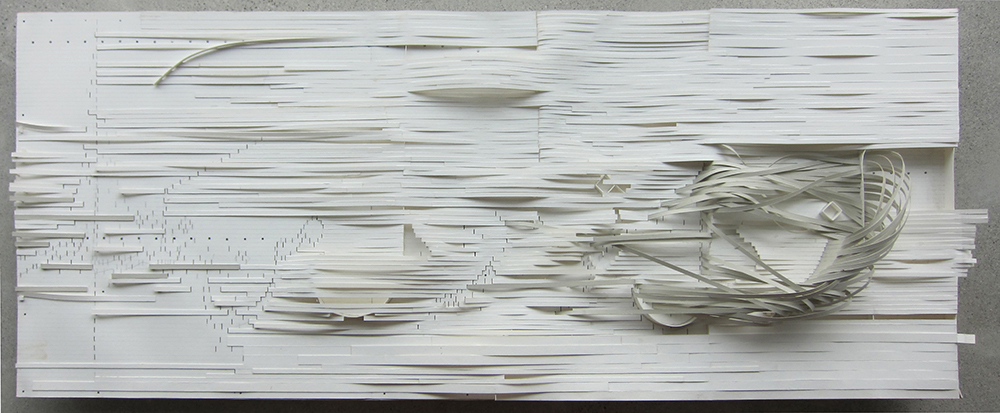

©Golnar Adili, From Your Heart to My Heart There Are References, 2008 1/4 inch museum board strips hand-cut and layered 23 x 53 x 11 inches, This work is an investigation of a Rumi stanza through treatment of the Farsi text as foundation. Here, the gray strips enter the word “heart”, from the word “from”, creating an eruptive moment around the word heart. The movement dissipates towards the word references, which is cropped at the end of the stanza on the left.

GB: Talk about your practice and deconstructing memories and reconstructing them with your father’s archive of letters and photographs?

GA: A decade after I lost my father to an abrupt onset of cancer at the age of 57, I was finally ready to begin reading the documents and letters I had boxed away at the time of his passing. I was only a few years into pursuing art seriously then. It was astounding what I found in my father’s small storage unit in Northern Virginia right after his death: stacks and stacks of meticulously archived letters I had sent to my father during our long years of separation, letters my mother had sent to him, letters he had sent to his comrades, pamphlets from the CISNU and other leftist groups, photos of his life, and even photocopies of what he had mailed. This was at once his personal archive and an archive of the leftist opposition to the shah, and I have been working with this material ever since. His archive is the impetus behind my art practice today, which is an extended effort to review and process our tumultuous revolutionary past through zooming into their emotions from passport photos, my parents’ handwriting and words. It was interesting how I literally woke up in the middle of the night after ten years had passed from my father’s death with a feeling of urgency and that it was time to start digging into these boxes, letters and photos to start piecing the past together. This journey was not easy. I would get overwhelmed so many times and had to stop going through the letters. I both wanted to read the details and didn’t want to read them because it hurt. I took everything to Smack Mellon for a year-long residency in order to go through them and all was flooded with Sandy, the storm in 2013. Thankfully I salvaged all of the letters and photos with tremendous help from friends and my community. The MacDowell Colony reached out to me to invite me for a residency to only focus on this archive. There I digitized everything. Unfortunately all of the books were destroyed which I was hoping to include in my own library.

For a long time I was not sure what to do with this material and after a lot of experimenting and agonizing I told myself that I would do with it what I do with everything else, to take it apart (deconstruct) and put it back together (reconstruct). In this process usually things are not added from outside or taken out of the original, but given depth and texture. The art pieces resulting from these investigations usually convey my relationship to the original document formally. I am very interested in emotionality.

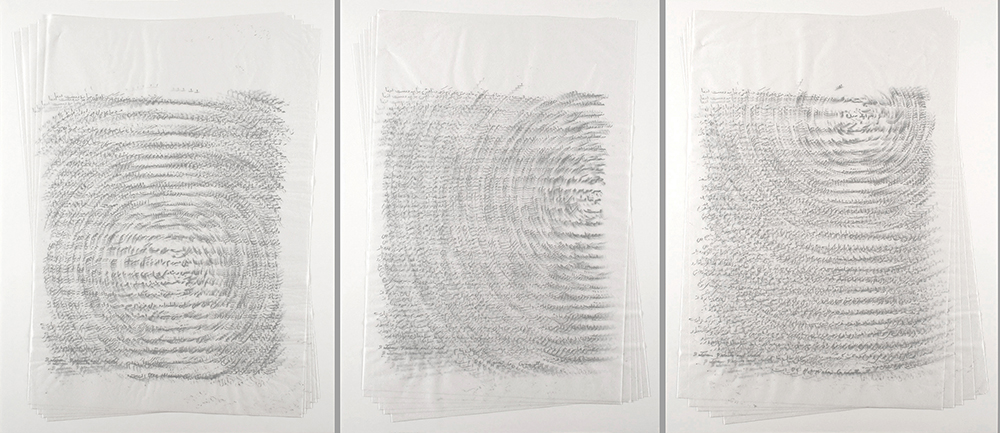

©Golnar Adili, The Letter Tryptich, 2012 Screen Print on six tissue papers rotated per set. Each set is composed of six identical letters rotated around a word or a cluster of words. The letters in each set are identical to one another replicated from a letter my mother wrote to my father while in their first year of separation forced by the tumultuous political climate of Iran. 24 x 36 inches per set

GB: There are a lot of people who are afraid to try something new. You seem very open to working with different materials. What inspires you to keep evolving in this way?

GA: I love material and different processes. It is fun to play, but also each material has its own language which is fascinating to me. I love the photographic, but only those photo-based processes which give materiality and depth to the image to combat the flat visual world of screen and digital prints we live in excited me.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026