Photographers on Photographers: Zachary Kaufman in Conversation with Matt Eich

Matt Eich is a tenacious storyteller, whose work is largely defined by long-term projects that offer intimate depictions of the American condition. I first saw Matt’s photographs as a featured alumni on the Eddie Adams Workshop site in 2006. At that time, I was early in my newspaper career and looking for community-based stories with impact. I remember being struck by Matt’s ability to portray people with dignity and approach communities with reverence. His patient approach to storytelling produces narratives filled with quiet moments that can feel significant, yet simultaneously ordinary and relatable. As I searched for opportunities to produce meaningful work, Matt’s photographs depicting people’s pride, fear and hope, provided inspiration.

In support of my goals to pursue personal projects, I returned to graduate school mid-career. While preparing an edit for my thesis exhibition in Spring 2022, I was in need of an outside perspective. I reached out to Matt, introduced myself and asked for his assistance with an edit. He agreed to help me, a stranger, find visual threads and a cohesive narrative that would function in a gallery setting. His input made my exhibition stronger, and his gesture reminded me just how wonderfully supportive the photographic community can be. Thank you Matt.

Matt Eich is a photographic essayist working on long-form projects related to memory, family, community, and the American condition. He is the author of four monographs of photography and his work is widely exhibited and held in public collections including the Chrysler Museum of Art, Cleveland Museum of Art, Do Good Fund, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and others. Matt’s projects have received support from an Aaron Siskind Fellowship, two Getty Images Grants, a VMFA Professional Fellowship and an Aperture/Google Creators Lab Photo Fund Grant. He was an artist in residence at Light Work in 2013 and at a Robert Rauschenberg Residency in 2019. Eich teaches at Corcoran School of the Arts & Design at the George Washington University. He makes books under the imprint Little Oak.PRESS and lives in Virginia.

Follow Matt Eich on Instagram: @matteich

© Matt Eich, Clayton riling Shank and Money, From the series, Carry Me Ohio, Carbondale, Ohio. 2007.

Zachary Kaufman: It can be difficult to be present in the moment while you’re also making pictures. How do you allow yourself to experience the things that you photograph in a meaningful way?

Matt Eich: You are right that the photographer dance is a tricky one – how to be emotionally engaged and present while also removed enough to see things clearly and render a scene in a lasting way? I advocate for young photographers getting to know their tools the way a musician knows their instrument. When it comes time to make, you don’t want to be caught up in the technical, you want to be in a somewhat Zen state, so the camera is less of a barrier between you and what is unfolding and more of a conduit for channeling a shared experience. This is idealistic, but occasionally comes to fruition.

ZK: After forming close relationships with those you photograph, I imagine you feel protective to some degree. How do you depict people in an honest and revealing way while maintaining their trust? Some of the relationships that you cultivate through your work seem to be enduring, can you talk about the challenge and importance in maintaining relationships?

ME: My goal for making images is to depict strangers with the same degree of intimacy and respect as my own family. In making long-form projects trust is essential, so I need to engage in an open dialogue with the people I’m collaborating with about how I see them, how I intend for the images to function, and listen to their thoughts on how they want to be represented. We all change over time, projects evolve or “finish”, but relationships can endure. Photography is beautiful because a fleeting encounter can last forever, but I think that generally, intimacy is best formed organically, over a long span of time.

ZK: Author and editor Bill Shapiro wrote that one of your many gifts is a long attention span. How do you stay engaged and motivated with a single project over such a long period of time?

ME: That was a kind thing of Bill to say, though I’m not sure my wife would agree. I’m a bit ADD when it comes to daily life. OCD tendencies sharpen some organization, but I am constantly toggling between family, teaching, commissions, personal projects, grants, publications, editing work for other people, reading poetry, tinkering on the piano, or working in the yard. This is all to say that I’ve usually got a few projects in various stages happening at the same time. Right now, I’ve got two book edits in different stages, one or two other nearly book-ready things and a project that I’m still actively adding to for the next 2 years. While my projects span a long period of time, it’s not like I’m getting to work on them every day – I’m slowly chipping away at multiple things simultaneously. For much of my life I’ve been in a rush. These days I’m trying to embrace what friend and former assistant Sam Owens calls her “turtle energy.” The key to being able to sustain a body of work over an extended time span is the questions the work generates. Does making the work keep scratching the itch, allowing me to unspool question after question that has no answer?

ZK: With projects that span years, the editing process can be complex. Can you describe your approach to editing long-form essays? How do you balance the need to find focus while maintaining flexibility to allow the story to develop in an organic way?

ME: Usually what I start out intending to make isn’t what comes out in the wash. The longer I give it to cook, the more nuanced it tends to be. Depending on the work, I’ll be drawing down from at least hundreds, if not thousands of frames made over many years. I’ll do a wide pull and often share that with an editor named Mike Davis or a trusted group of peers. Mike and peers will pull their selects from the larger set, and I’ll work with the publisher to narrow in on our selects and begin working on a sequence. There are always compromises – pictures included that I feel just OK about, or pictures cut that I am fond of. The sequence is a slow and organic process that involves making work prints, playing with them on the table / wall, going back and forth between InDesign and the wall, making maquettes, etc. before arriving at something that feels final and ready for press. I try not to be too rigid with my thinking because a final work should always be more complex than we initially envision.

ZK: Have you made an image that you were excited to share, but left out of your edit after people featured in the photograph or others in the community raised concerns regarding representation? If so, can you describe how you navigate such challenges?

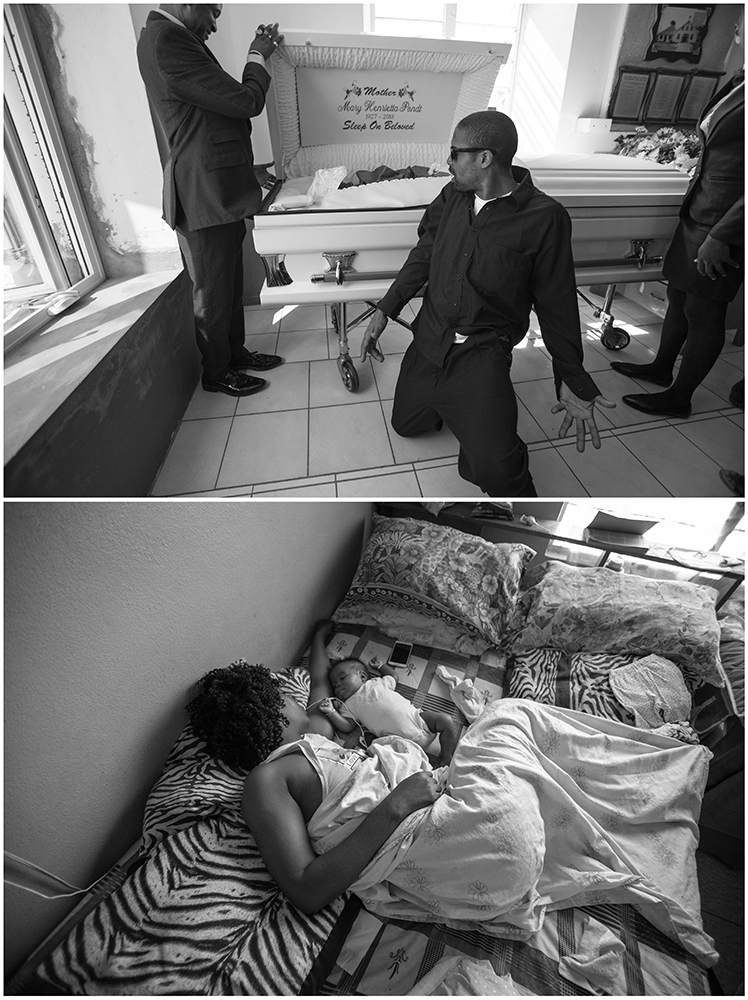

ME: Certainly – I am not always able to be in dialogue with people that appear in photographs, but when I am, their input is important. In the project, Sin & Salvation in Baptist Town I shared an early book maquette with one of the main characters, Winky. He took the maquette around the neighborhood and solicited feedback from community members. Most people seemed to think it was a fair and accurate depiction of the place, but some of the older community members thought that depictions of guns or drugs were not necessary to give a sense of their community. It’s subtext, not foreground. This input really helped shape the final book when it was coming together.

ZK: I feel that your earlier work has a vicarial and raw quality to it. In contrast, your more current work is filled with soft and quiet moments that seem almost meditative. Do you also see this shift in your work? If so, does it reflect a change in your personal point-of-view?

ME: That’s an apt reading of a shift that has been occurring in my work over the years. I think as a young photographer trying to support a family, I felt it was necessary to make work of a certain volume and that influenced my technical decisions at the time (35mm, color, digital). As I’ve grown older, I’ve drifted towards a quieter, slower, more intentional way of working (6×7/4×5 B&W), which in turn shapes the resulting images. Over the years I’ve opened myself up to a wider range of influences outside of photography (music, poetry, painting), which weaves its way into my subconscious, and into the work. I’m fortunate to teach full-time, which has afforded me (at least in recent years) some additional support to make my work in analog, as it is slow and costly. Without the support of my job, I would have to impose other limitations on my work. Those components aside, I think as a young man and young father looking at America, the experiences I had felt raw, and as I’ve grown older, I’ve tried to become softer and more tender, and the pictures follow.

© Matt Eich, Maddie’s braids, Charlottesville, From the series, I Love You, I’m Leaving, Virginia. 2016.

ZK: I understand that you have to be creative while funding long-term projects. Can you talk about how you financially support that type of work?

ME: Creativity is required for every facet of making long-form projects, including funding, and disseminating the work. It’s a saturated market, so it can be difficult to push ideas through and find support. In my experience, it is important to have the foundation of a project (a few strong images, and some articulation of the point and purpose of the work) before you start the process of seeking out support. Think of editorial outlets who might want to assign you to tackle a small piece of a large project, look for local, regional, national, and international opportunities that you’re eligible for. Think about your work through different avenues of interest and consider who might wish to support what you are doing? Over the years I’ve been fortunate to occasionally receive grants to support my projects, but the few that I receive are out of dozens of applications that are rejected. The process of application and rejection is standard – the goal should be to improve your application each time. Several grants I’ve received I applied 5+ times before being selected. It’s important to be persistent. Always get outside eyes on your application and edit if you can. Pay attention to the details. Apply, apply, apply. The more lines you have in the water, the more likely you are to get a bite.

© Matt Eich, Quan waking up, From the series, Sin & Salvation in Baptist Town, Greenwood, Mississippi. 2011.

ZK: You own a small independent publishing house, Little Oak Press. How do you utilize this space currently and what is your vision for it moving forward? At a time where everything exists electronically, where do tangible forms of photographic storytelling fit in?

ME: Little Oak.PRESS started as an experimental space for me to play with printed matter and different edits / sequences of ongoing projects. It was never meant to be overly serious if I’m honest. It has started to expand a little bit, delicately stepping into releasing work by other artists. We started with a book by an old friend of mine named Rich-Joseph Facun, called Little Cities, the second volume of Pictures & Poems, featuring Al J. Thompson and Tanio M. MacCallum and Field Guide to A Crisis by Justin Maxon (less photo-driven, more social practice piece). Right now, I’m comfortable occasionally collaborating with a friend who I trust, but every publication is a gamble – if I don’t break even, I can’t keep making them. Currently I don’t have any Little Oak.PRESS projects in the que because I need to push through a few books of my own from different publishers over the next couple of years (We, the Free via Sturm & Drang and Say Hello to Everybody, OK? via GOST).

© Matt Eich, R.I.P. Jack Jr., Charlottesville, From the series, I Love You, I’m Leaving, Virginia. 2016.

ZK: As an Assistant Professor of Photojournalism, what is your approach to mentorship? Is there someone specific who has played a role in your development as an artist, that you attempt to emulate while serving as a mentor to your students?

ME: I’m fortunate to have had some wonderful mentors over the years. Rich-Joseph Facun is someone I met early on who has encouraged, challenged, and supported my work in many ways over the years. During my time in undergrad at Ohio University I had some wonderful professors, including Bruce Strong, Stan Alost, Marcy Nighswander, Terry Eiler, Chad Stevens and others. Those interactions really shaped the way I view mentorship and interacting with students. I love looking at work by photographers who are hungry to grow and learn. That energy and curiosity generally feeds back into my own practice. Now that I’ve been teaching for 6+ years, I’m starting to realize how the academic year empties my creative tank. Right now, I’m coming off two days of dedicated project work, which feels exhilarating. The school year is around the corner, so I feel the need to make while the making’s good.

ZK: During a previous conversation, you mentioned that your students take an unorthodox approach to documentary photography and photojournalism. Can you describe how they approach photojournalism? How do they envision the future of documentary photography?

ME: In that conversation we were talking about some differences between my undergraduate experience and what I try to facilitate as Program Advisor for the BFA in Photojournalism students at Corcoran School of the Arts & Design at the George Washington University. My undergraduate experience felt like we were jammed into a mold for making photographs that was already outdated. The program where I teach is situated in a Studio Arts program, so I find it a much more open-ended atmosphere that encourages experimentation. At least in the few years I’ve taught here full-time students have consistently pursued non-traditional documentary projects for their senior thesis, often with a deep personal connection to the work that would’ve been frowned upon when I was in school. You’d have to ask my students how they envision the future of documentary photography, but it’s generally more personal, vulnerable and self-aware than what I was making at their age.

ZK: You’ve effectively used geographic threads to help shape cohesive narratives, yet your work transcends typical “place’ stories. Instead, it seems that place functions to illustrate shared experience, collective memory and a sense of inescapable destiny. Now that you are living, making work and raising children near your own childhood home, have those themes taken on new meaning?

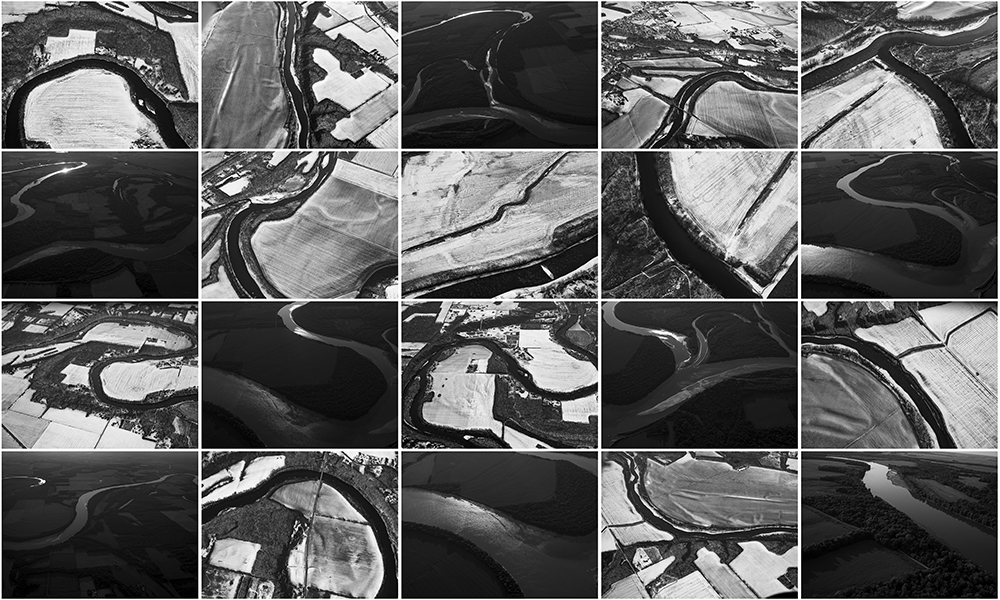

ME: In these projects about place, I’m viewing the geography as a stage for a variety of natural and human happenings to unfold. I’m considering how history has shaped the present in these places. What geographic, political, socioeconomic forces have played a role? What does community look like or feel like in this place? The work that is closest to my childhood home is the third volume in The Invisible Yoke series: The Seven Cities. That work was made while I was raising my kids in the same region where I grew up. We’ve moved away from that area to central Virginia nearly 8 years ago. My latest project, Bird Song Over Black Water looks at the state as a whole and certainly still grapples with questions of history, collective memory, family, and destiny that pervade the earlier work. The voice I’m using is different now – quieter, maybe less certain of anything. The series feels like a step towards owning my natural voice.

© Matt Eich, Wrestling with Jesse in the backyard, From the series, I Love You, I’m Leaving, Columbus, Ohio. 2015.

Zachary Ramón Kaufman is a visual storyteller whose work explores the generational inheritance of land, values and socioeconomic status. Zach is also interested in collaborative projects that benefit vulnerable populations. He graduated with a BA in Journalism from San Francisco State University and during that time, served as photo editor for the Bay Area Multicultural Media Academy. Zach is an alumni of the The Associated Press Diverse Visions, Eddie Adams and Mountain Workshops and worked as a staff photojournalist on the West Coast for 10 years.

In 2022 he earned his MFA in Photography from Indiana University Bloomington and, most recently, served as the Communications and Media Consultant to the IU Prison Arts Initiative. Currently, Zach is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Photography and Visual Communication at Webster University in St. Louis, Missouri.

Follow Zackary Kaufman on Instagram: @instakauf

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Mehrdad Mirzaie in Conversation with Liz CohenSeptember 4th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Elizabeth Hopkins in Conversation with Nicholas MuellnerAugust 21st, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Cléo Sương Mai Richez in Conversation with Shala MillerAugust 20th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Emma Ressel in Conversation with Tanya MarcuseAugust 19th, 2025