Jiatong Lu: Nowhere Land

For the next few days, we will been looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Jiatong Lu and I discuss Nowhere Land.

Jiatong Lu is a mixed media artist and photographer based in New York. Born in 1988, she grew up in Northwest China and graduated with an MFA in Photography, Video and Related Media from the School of Visual Arts. Her artistic practice centers around the exploration of physical and mental trauma, delving into the intricate connections between personal memory and collective cultural memory, as well as the interplay between individual experiences and social policies. Jiatong’s work has been exhibited at Candela Gallery, Richmond, VA; Filter Space, Chicago, Illinois; Woodstock Artists Association & Museum, NY; The Rockaway Artists Alliance, NY; The 3rd Beijing International Photography Biennial, China; Shangba Gallery, Beijing, China; The Charta Festival, Rome, Italy; LoosenArt Gallery, Rome, Italy and others. She has received awards, including an Honorable Mention from York Center for Photographic Art (2022), and a 2019 NYFA Artist Fellowship in Photography from The New York Foundation for the Arts.

Follow Jiatong Lu on Instagram: @jiatonglu_

Nowhere Land

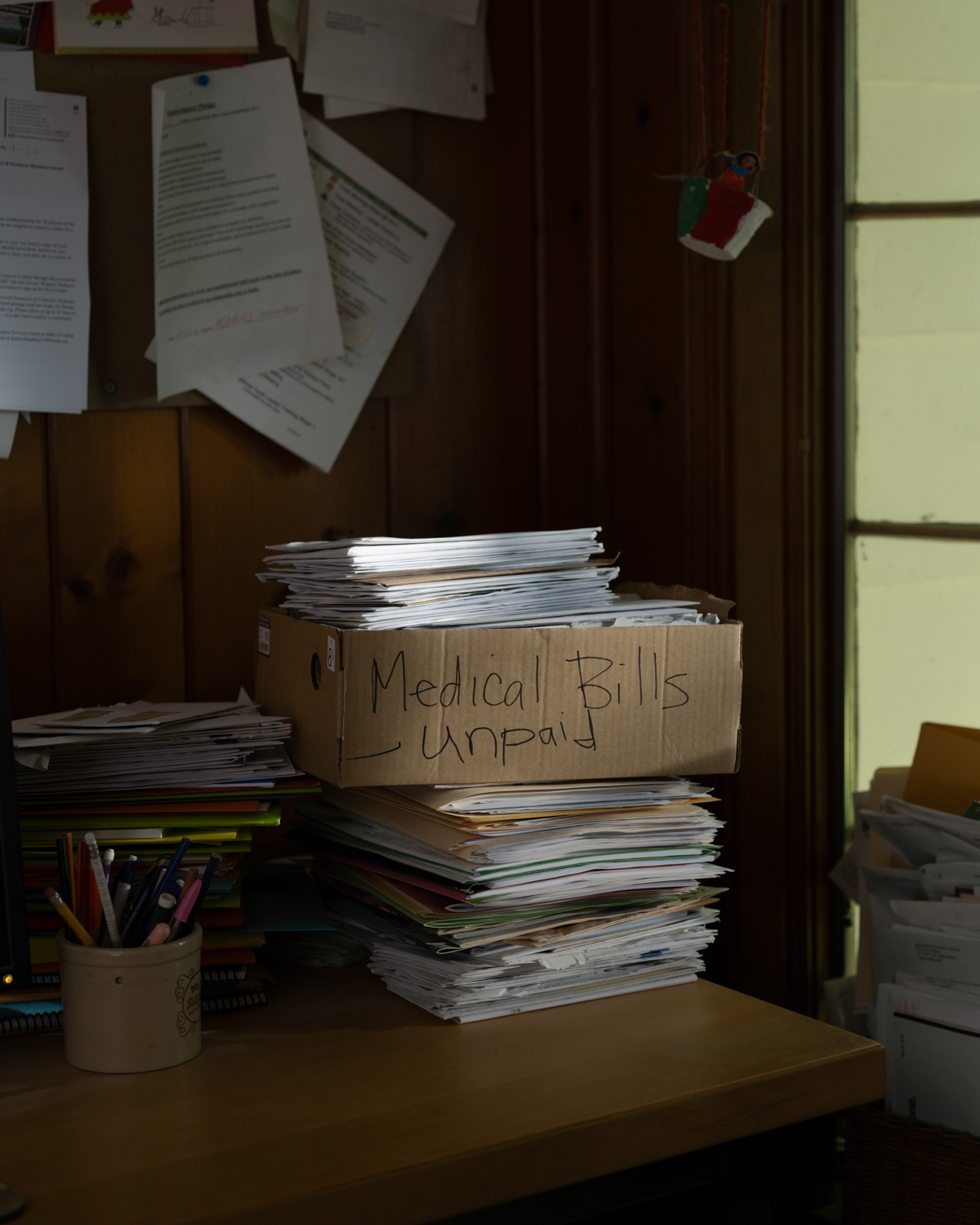

My current ongoing project is focused on the plight of people living with chronic Lyme disease and tick-borne illness. In 2021, I developed a series of terrifying symptoms. Based on my symptoms, I was diagnosed with Neurological Lyme disease and co-infections. Like most other chronic Lyme patients, I have undergone a lengthy treatment and gradually accepted the fact that I may never fully recover. For a period of time, I could not walk, think, read or sleep, and was suffering from severe headaches, brain fog, stiff neck, fatigue, joint pain, anxiety and depression. I completely lost the capability for even basic life tasks. Meanwhile, I also had to cope with huge financial stress, since the CDC and insurance companies do not recognize chronic Lyme disease. As a result, all expenses for my ongoing treatment are out of pocket. It’s difficult to imagine how those with chronic Lyme disease manage to endure this situation for years.

Each year approximately 476,000 people in the united states are diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease. An overwhelming number of Lyme patients were misdiagnosed by doctors in the early stages of the disease, because of inaccurate testing and misleading information provided by the CDC. Doctors who do not specialize in Lyme disease choose to follow the CDC’s outdated treatment guidelines and virtually ignore the patients’ suffering. Apart from the symptoms, many chronic Lyme patients have to deal with the inability to work or attend school, isolation from family and friends, trauma from medical abuse, and tremendous financial pressure. For decades, they have been waiting for an answer from the medical system. They are angry, they are afraid, they feel betrayed by their own bodies, isolated, unseen and unheard, as though trapped in the middle of nowhere.

Daniel George: You write that this work began after your diagnosis with Lyme disease in 2021. Would you share more about the development of the project over time—and your intentions with focusing on your lived experience?

Jiatong Lu: My art practice consistently stems from my own experiences, often driven by emotions such as confusion, doubts, helplessness, and, at times, anger. For me, the process of creation serves as a profound exploration of the complex relationship between the self and the outside world, sometimes providing a sense of healing. In the context of my current work, Nowhere Land, living with chronic Lyme disease on a daily basis has given me a profound understanding of the frustrations that come with this debilitating condition. When I began this project, I was burdened with countless questions that seemed inscrutable. However, the progression of the project has brought clarity to the issues and problems I initially grappled with. This journey has not only deepened my understanding of my own struggles but has also allowed me to shed light on the invisible battles fought by countless others.

When I contracted Lyme disease, the standard treatment suggested by the CDC didn’t alleviate my symptoms. Desperate for relief, I embarked on an extensive search for alternative treatments, consulting various doctors as new symptoms emerged. During this process, I discovered a substantial Lyme community online—a community that had long remained invisible to the public eye and had endured mistreatment for decades. Motivated by the stories and experiences shared by individuals living with chronic Lyme disease, I have started my ongoing project: Nowhere Land. To date, I’ve had the privilege of engaging with over 20 individuals from diverse backgrounds. Among the participants are parents and children who all live with severe chronic Lyme disease and co-infections. I am currently still in the process of documenting their stories. In addition to capturing these personal narratives through photography, I’ve expanded the scope of Nowhere Land by collecting archival materials, texts and objects from chronic Lyme patients.

DG: In your statement, you outline many of the difficulties facing chronic Lyme patients, including some of the physical, social, and financial tolls. Could you talk more about the significance of bearing witness to these experiences?

JL: Back in 2021, when I was diagnosed with Lyme disease, my life turned into a daily battle against debilitating symptoms—severe headaches, brain fog, joint pain, nerve pain, anxiety, depression, and more. Basic tasks became impossible, leaving me unable to work for nearly one and a half years. After undergoing two years of Lyme disease treatment, most of the terrifying symptoms have either subsided or become more manageable. Yet, I am acutely aware that my body is gradually declining. The unpredictability of flare-ups, severe insomnia, and overwhelming anxiety make most days a challenge. The pain and fatigue are relentless, draining both physically and mentally.

Financial stress adds another layer of difficulty. Chronic Lyme treatments are lengthy and expensive, and insurance companies do not cover the treatments. However, compared to severely ill Lyme patients, I am comparatively more fortunate, having some support from my family and partner, which many chronic Lyme patients lack.

My neighbor, Barbara, was the first subject of the project. Witnessing her journey is a stark reminder of the heartbreaking realities within the Lyme community. Barbara has battled Lyme symptoms since high school, but her diagnosis came 35 years later, coinciding with her son’s similar symptoms. Tragically, her son was also diagnosed with congenital Lyme disease. Despite her obvious distress, Barbara faced a series of dismissive misdiagnoses, from menopause to fibromyalgia and more. To prove her condition wasn’t menopause, she had to demonstrate her son’s symptoms; he, too, walked like a very old man. Over time, her health deteriorated, leading to Lupus, Sjogren’s syndrome, scleroderma, and disruptions in thyroid function, liver enzymes, and balance. Financially, Barbara spent her life savings on Lyme treatments. Her debilitating symptoms forced her to quit her acting career, resorting to a part-time job to meet basic needs. Wrongful job loss left her unable to pay rent, resulting in eviction, leaving her at risk of homelessness. Moreover, her family and friends struggle to understand her invisible suffering, compounding her isolation.

Barbara’s story is unfortunately quite common within the Lyme community. Bearing witness to stories like Barbara’s emphasizes the urgency for understanding and recognition. Many Lyme patients are dismissed and blamed, their pain invalidated, their suffering are just in their head. It’s a deeply isolating experience when even family members and doctors fail to comprehend the invisible torment these patients endure daily.

DG: Your writing and photographs extend beyond the personal and seek to include others’ circumstances and experiences as well. Why did you feel it was important to incorporate these voices in your work?

JL: In my practice, I always ask myself how I can transform my personal experiences into something universal and what can art do for our society. While this project does stem from my personal journey with Lyme disease, its scope goes far beyond my individual experience. There is a vast number of people silently suffering from this disease, sharing a journey that remains invisible to the public eye. Through each person’s unique story, I aim to paint a comprehensive picture, showcasing not only their struggles but also shedding light on the systemic challenges within the US medical system.

DG: In your biography, you mention that your work “primarily focuses on the subjects of family, trauma, personal memory, historical memory, and explores the inter-relationships among them.” What about photography makes it particularly suited to address these broader interests of yours, as well as this project specifically?

JL: When I first encountered photography, I was deeply attracted to this medium. The way photography communicates, both personally and publicly, resonates deeply with me. The themes I focus on, such as family, trauma, personal memory, and historical memory, are all intertwined with my personal experiences and memories. Photography serves as a medium that allows me to explore my inner emotions and establish a connection between myself and the outside world.

Photography, in a specific sense, offers a unique form of realism. For me, it functions as a dialogue, enabling communication with both myself and others, providing more space for imagination and emotion compared to words or texts. It captures the essence of my experiences and emotions in ways that words often fail to express.

For the Nowhere Land project, I plan to incorporate various elements beyond photos, including texts, archival materials, and installations. Each medium has its unique function, allowing me to explore different facets related to this theme effectively. Through this multidimensional approach, I aim to create a comprehensive and immersive experience that conveys the complex issues that are related to Chronic Lyme disease.

DG: You mention that this project is ongoing. Would you mind sharing how you envision it continuing to evolve over time (and perhaps culminating at some point)?

JL: This project is undoubtedly a long-term endeavor. Currently, I am in the process of documenting Lyme patients on the East Coast. I am actively seeking funding to sustain this work, although the application process has proven to be more competitive and challenging than anticipated. My goal for the upcoming year is to extend the project to Central and Western America. Eventually, I am eager to transform this project into a photobook, a format that I believe will be highly suited for its presentation.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026