Monumental Ruins, Foundational Reforms: Santiago Porter In Conversation with Vicente Isaías

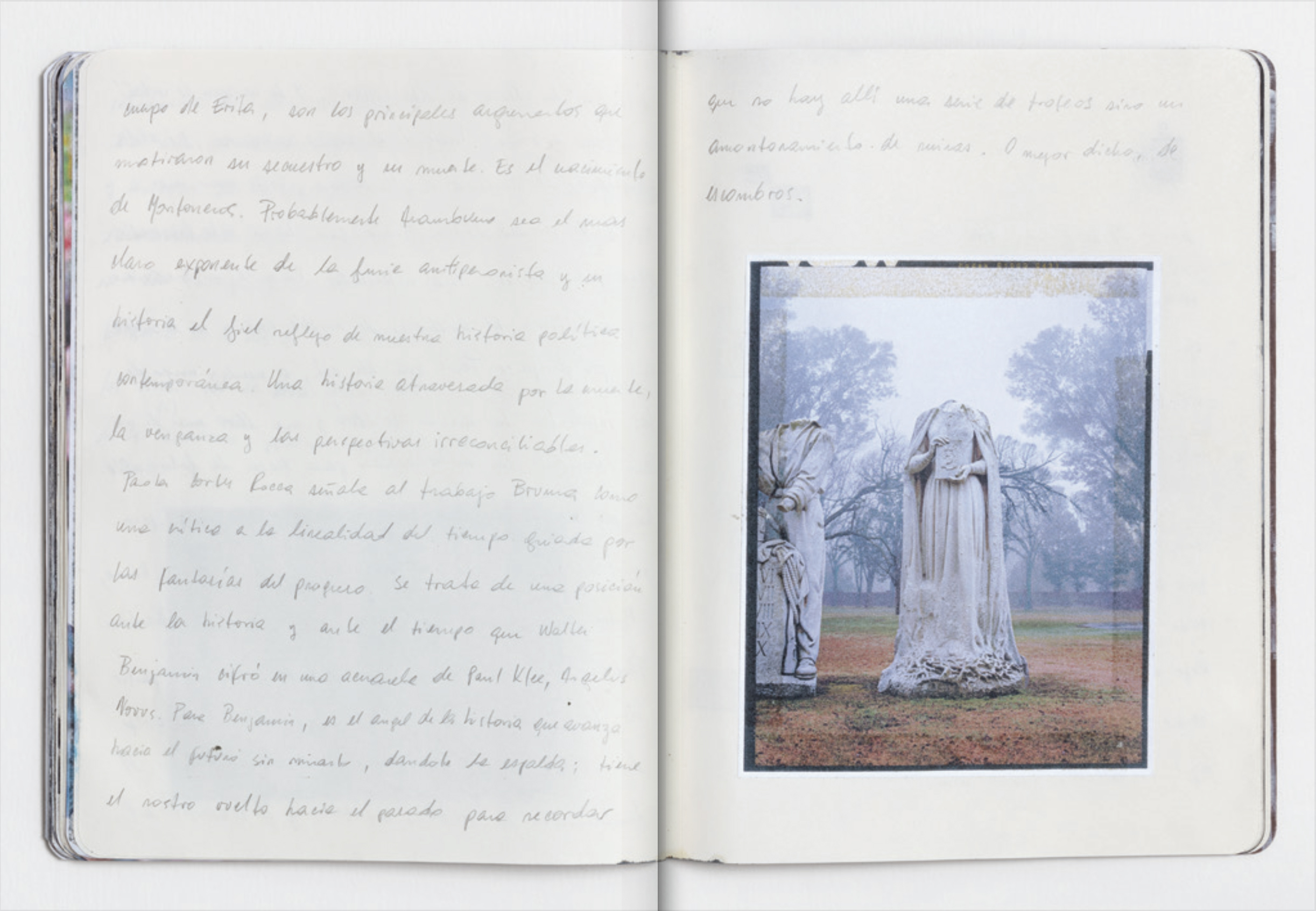

In the photograph ‘Evita,’ one can see the decapitated sculpture of Eva Perón and to her left… President Juan Perón, headless and handless. After Evita’s death in 1952, Perón commissioned the sculptor Leonne Tomassi to create a set of sculptures to be placed on the façade of what was to be the mausoleum where the embalmed remains of his wife Eva Duarte would rest. During the military coup of 1955 [they] were immediately seized and thrown into the Riachuelo in the City of Buenos Aires. The sculptures were rescued 40 years later and placed in the Quinta 17 de Octubre. Today, Perón’s remains also rest there. © Santiago Porter, “Evita,” from “Bruma,” 2008. Courtesy the artist.

Santiago Porter’s work highlights the nexus of violence, politics, symbols, and public memory in a way that is extremely critical today. His large format, dystopian photographs of decaying state buildings and desecrated monuments reflect on the aftermath of the last decades of political turmoil in Argentina and the scars left by such events — both on the physical environment and the collective psyche. More profoundly, they beckon us to wonder how the ruins of our future are presently being orchestrated.

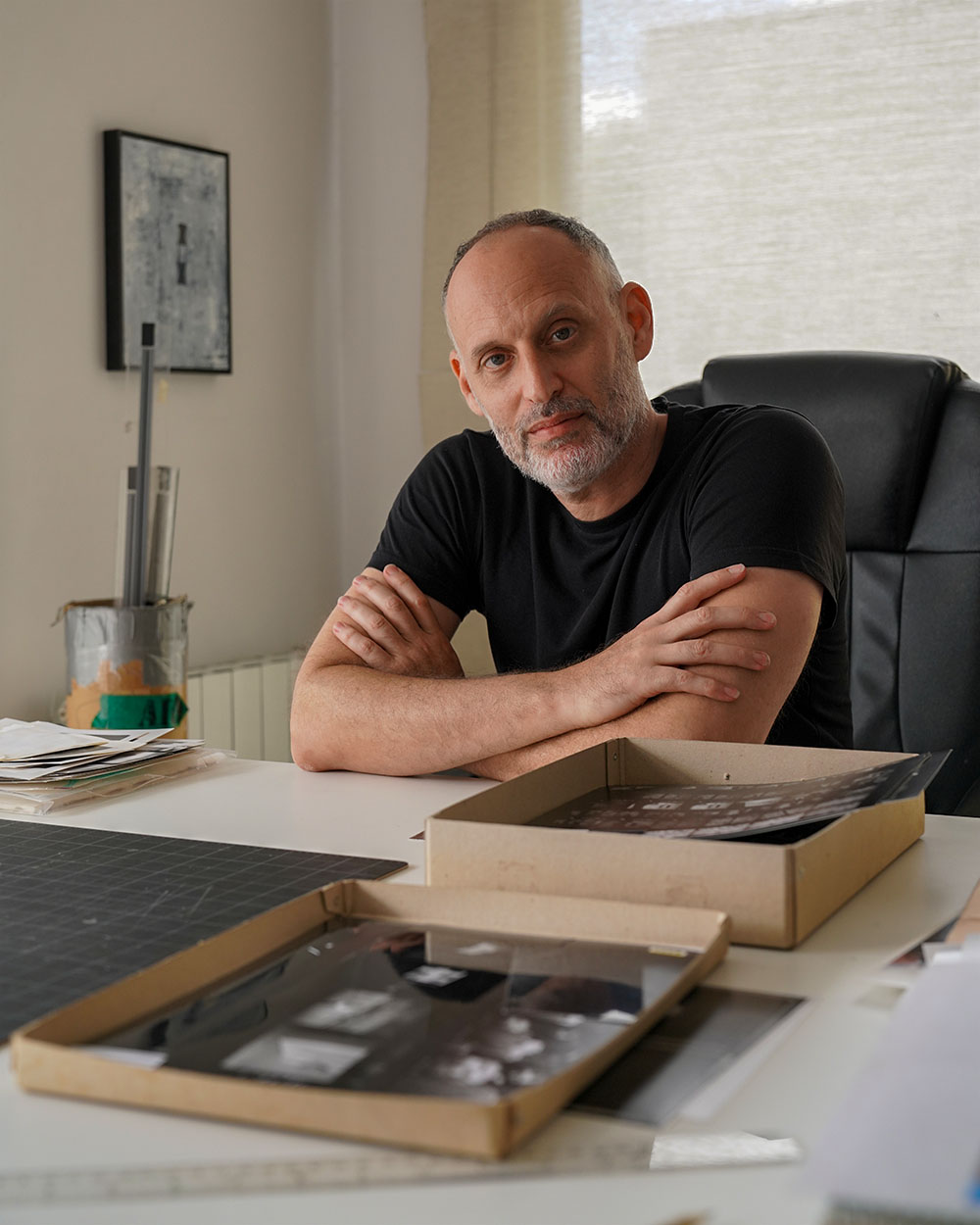

In this exclusive studio visit for Lenscratch, Porter and I met at the artist’s studio in Villa Crespo, Buenos Aires, to discuss over a glass of orange juice the political edge of his internationally acclaimed art trajectory, its relevance today, his early days as a photojournalist, and his departure from — and possible reconciliation with — photography.

Santiago Porter en su estudio en Villa Crespo, Buenos Aires, 3 de enero, 2024. Fotografía ©Vicente Isaías

Santiago Porter (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1971) has been awarded with distinctions and received many accolades, such as the Guggenheim Scholarship (2002), the Fundación Antorchas Scholarship of Buenos Aires (2002), the First Award of Photography by the Central Society of Architects of Buenos Aires (2007), the Petrobras – Buenos Aires Photo Award (2008), the National Scholarship by the National Fund for the Arts (2010) and was selected to take part in the Artist’s Program at the Universidad Di Tella in Buenos Aires (2011). In 2022 he received de Konex Award for the Visual Arts. He has published numerous books such as “Pieces” (2003), “The absence” (2007) and “Mist” (2017). He has been featured in important leading national and internationals publications. His work has been shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Colombia, Ecuador, Chile, United States, Spain, France, Germany, Switzerland and Egypt. Nowadays, his work is part of important national and international collections such as Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires – MALBA (Argentina), National Museum of Fine Arts – MNBA (Buenos Aires, Argentina), Museum of Modern Art of Buenos Aires – MAMBA (Argentina), Museum of Contemporary Art of Rosario – MACRO (Argentina), Provincial Museum of Fine Arts Emilio Caraffa, Córdoba (Argentina), Museum of Art and Memory of La Plata – MAM (Argentina), Museo en los Cerros, Jujuy (Argentina), Museo de Arquitectura de Buenos Aires – MARQ (Argentina), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (USA), JP Morgan Chase Collection, New York, (USA), Fondation Antoine de Galbert, Paris (France), Petrobras Collection (Argentina), Rabobank Collection (Argentina), among others. Santiago Porter is currently a Professor at the Department of Social Sciences at the University of San Andrés and in the Photography Degree at the National University of San Martín.

Argentine Week featured artists from top left to bottom right: Santiago Porter, Juan Cruz Olivieri, Javier Bertín, Valeria Sestua, Angela Copello, Karen Navarro, Julieta Christofilakis.

Vicente Isaías: Santiago, you haven’t been in your studio for a week. Thank you for having me. What’s the first thing you’d like to do now that you’re back?

Santiago Porter: To inaugurate my 2024 journal. I have it there, ready. My notebooks are where I jot down my things. I eventually draw, do some painting, [include] photos, and jot down the things that occur to me and on which I would like to work or am working on. This year it happened that just my journal from last year concluded with the end of the year, and that’s something that had never happened before. … Never, it had never been so precise.

VI: Everything synchronized!

SP: Clearly. So now there’s a journal there on the desk and I just wrote “January 20 and 24” on it.

VI: It must feel very good to start your journal and the year in unison.

SP: Of course. In general, I try to start it as soon as possible: to desacralize the blank notebook. The blank notebook invites you not to spoil it. I always try to spoil it as soon as possible.

Replica of the sculpture of Eva Perón and its photograph in Santiago Porter’s studio, on a shelf next to filing cabinets, January 3, 2024. © Vicente Isaías

VI: And creatively, do you already have any ideas brewing that you want to capture on the pages of your 2024 notebook?

SP: Several things are happening. First, there are the things I’ve been working on, writing personal things. [But] for some time, I’ve had the illusion of returning to photography in some way. There’s something that has been happening, especially towards the end of last year — and now that feeling continues, which has to do with the new political and social situation that Argentina is going through — that somehow makes me think about the possibility of returning to photography. I have no idea how, when, or what it should be, but just having the desire is a lot.

VI: Considering the political edge of your work, I have no doubt that you would want to return to photography considering the political shakeup with Milei. What concerns you the most about what’s happening?

SP: Everything. All of it.

VI: All of it.

SP: In concrete terms, the measures that are already being implemented and then, of course, everything to do with symbolic issues. I feel that this administration that has just taken office in some way thinks and considers it important to destroy everything that I find important… (pause) And that’s a new feeling for me. Knowing that issues that were non-negotiable for me, that have to do with the dignity of life, of people, and with our own history, I consider it catastrophic.

VI: I agree with you. I firmly believe that our duty as cultural workers is to show solidarity and denounce when power bodies assume these kinds of ideologies that directly threaten the existence of our work. From the start, this government has planned to cut funds and suppress support for the arts. What impact do you think this trend towards precarization will have on future generations of artists?

SP: I see it in two ways, first, from the catastrophic state. This is something of another level, it’s a step further. It’s a matter of ideology, of what is thought at the cultural and social level about artistic and heritage production. This is about what is prioritized — or not — also for the Government. It’s being said that the National Endowment for the Arts, for example, is going to be eliminated!

I only mention this as a concrete measure. This is not something that will eventually happen in a distant future… No, in the next few hours! That’s why I tell you, the will to exterminate — in some way — cultural production and heritage exists. It’s no longer even disinterest, which we have experienced. It was never a priority for any administration. That, that is very clear. Now it’s about defunding, precarity.

But it seems to me that there is an additional step here, which lies in concretely eliminating the representation and support of cultural production in our country. Eliminating the National Endowment for the Arts, for example, is something very serious, and in symbolic terms, a statement of what is considered essential for a society.

VI: And what a statement, right? It’s very important to question under what context we are given the possibilities to create or not, and what a government considers essential for a fair society. And second?

SP: Right. Now, secondly — and this is something we discuss at the university, at least with my closest students —, it’s good to ask ourselves: Should we, even in precarity, produce as a way to resist, right? Resistance has always been there, from the perspective of art. [Creating as resistance] for me is a function, not a responsibility, but it is a possibility, and especially in personal terms. And that always summons… a way to account, from subjectivity, one’s own experience about our relationship with what happens. In working, that possibility appears, the possibility of going through these situations by working, expressing, from personal experience, seems to me a deeper, more sensitive, and more meaningful way to go through these experiences, like the ones we are going through today. I’m not saying that [art] is going to change the state of things at this very moment, but at least from there it provokes, it produces heritage and legacy that will eventually allow understanding this in the future. And that seems super important to me.

VI: This last thing you mentioned makes a lot of sense, especially considering that your work has somehow always been linked to heritage, legacy, civic imagination, and more broadly, loss and memory. I’m interested in knowing more about why you abandoned, so to speak, photography.

SP: I believe we mutually left each other.

VI: You took a break!

SP: We took a break. (laughs) Sometimes it’s a natural process… I’ll try to summarize it for you. I started photographing when I was very young. I was still in high school and I embraced photography passionately, as a tool and as the language itself. I had a very long relationship with photography, and when one is so passionately dedicated to something from such a young age, on the one hand, there is something very good about the intensity and devotion, but also one denies oneself the possibility of experimenting or exploring other possibilities. … In some way, I neglected [things] that I would have liked to do and didn’t do. Much later [I gave myself that opportunity] to explore with other languages.

“The initial stages of “Bruma” focused specifically on the appearance of certain public buildings in the city of Buenos Aires. There are nine buildings constructed in the city between the late 1930s and early 1950s, each representing a different aspect of Argentina’s social and political life. … I decided to focus on the facades specifically and work on them as if they were portraits. Using this hyper-visibility as a resource with the intention of highlighting the different layers of history accumulated in that deteriorated architecture. Photographs of large dimensions like obsolete monuments.” © Santiago Porter, “Ministerio I,” from “Bruma,” Ministerio I, 2007, 127 x 158,6 cm. Courtesy the artist.

© Santiago Porter, “Edificio Militar I,” from “Bruma,” Ministerio I, 2007, diptych, 100 x 127 cm. Courtesy the artist.

VI: When one ends these long relationships, one changes a lot, how has your relationship with photography changed?

SP: I worked as a photojournalist for a long time and from a very young age, and that somehow also forced me to photograph a lot, very intensely and for a long time. When I was a reporter, I was told that I had to photograph. That’s the job every day. I started to feel a certain dissatisfaction in that way of working, and on the other hand, I started to develop personal work in opposition to that work I did in the newspaper every day.

I understand that during that period, I exhausted the desire to photograph and also changed my relationship with photography — from a very intuitive and impetuous relationship at the beginning, to a much more reflective and paused relationship that followed. That also somehow explains my way of working on each of the projects that I developed over the years in a more contemplative way, like Bruma, for example.

I had been working on this project for a long time. Bruma somehow implements that radical change in the way of photographing. That’s where I started to change radically, precisely from that reflexive photographing, to transition to a photography that demanded a much deeper reflection, a consciousness about what the image implies completely different. I dedicated a lot of time to it and worked with Bruma in a very meticulous, very dogmatic, very exhaustive way and a little bit towards the end of that project, I felt that what I had to give regarding my photographs was somehow settled.

VI: It’s remarkable the contrast between your more paused and meditative works and the spontaneity and immediacy of photojournalism. When you talk about feeling something that calls you back to photography today, do you feel any responsibility to actively make visible what is happening? How do you imagine this reunion?

SP: When I returned to photography after having left the profession [of photojournalism], I did it in an antagonistic way, different from how I usually photographed. I changed the tools, I changed my way of observing. I began to work on the residue and not on what was happening, on what we can recognize as the indelible marks of what happened where we live, [and here] the theme of memory is also linked. Today, I don’t feel that I would do that again because the situation demands me to work in real-time. I am not clear if I will really return to photograph in this context. I start to feel that there is something about all this that calls me to do it again. Eventually, if I decide to return to photographing, then I would not return to the plate camera and the reflective times of that format and medium limitations.

To answer the other part of your question, [I] don’t feel that I should do it, I don’t feel that I have a “responsibility.” But if there’s something that has always happened to me, it’s that when something challenges me, one way to deal with that is by working. … What work always provides me is … a space for reflection. Today, what is happening in Argentina challenges me. Maybe all this could call me back to another type of photography, to a type of photography that I did 20 or 30 years ago — to go back to the street to photograph. I am, of course, much older, I have much less energy, but I could do it, it could happen. To a large extent, it depends on how things evolve, and if I feel the desire or the urge to do it. The sense of urgency with what is happening weighs on me. That might demand me to go back to the street to photograph in a way, let’s say, I don’t know, more spontaneous, more intuitive, but the truth is that I don’t know.

VI: Returning to this transition to painting, why was it so abrupt?

SP: When I finished working on Bruma, I really had that feeling of being settled with photography… To think again about photographing… (exhales) What do I say, with what sense, what did I have again to pick up the camera?! It was exhausting, unthinkable, impossible. So when I turned 40, I decided to take a year off from photographing… and give myself that year to settle pending subjects, so to speak. I didn’t consider myself a painter, but I really liked painting, especially for some specific issues in relation to photography. In my particular case, in terms of practice, after many years of photographing uninterruptedly, when I turned 40 I simply decided to stop.

That year I did the Artists program at the Universidad Di Tella and had many painter colleagues in the context of the program… Many of my colleagues who saw… that I wanted to paint, somehow pushed me to do it. It worked very well at that specific time, because I don’t know if I would have done it alone. That is, if they hadn’t pushed me to do it, I don’t know if I would have done it. Especially because my colleagues were very loving and very talented, with a view of making completely different from mine, to this super dogmatic and structured view that I had at that time and with which I had been working for a long time.

VI: What were the frictions between photography and painting that caught your attention?

SP: The question that kept me awake at that time was: what do we ask of the image? Why do some images move us and keep us up at night while others leave us profoundly indifferent? I had this question very present when I was photographing… How? How to generate an image that lives up to what the image tries to represent in relation to what I wanted, what I wanted to work on with my photographs? Beyond the indexical nature of photography, what does it show you? What do you recognize? What is the connection we establish with what you see? And then there’s something else related to what the image proposes to you, what moves you or doesn’t move you. That’s where I thought about removing that initial condition that for me was always so important in photography and to work with the image from another place. In a way, that was what I was proposing to investigate or experiment with painting. Starting from zero and trying to generate an image that at the end of the journey, at the end of the process, convinced me.

Atril de Santiago Porter con una fotografía del oceano como una referencia pictórica. Fotografía por © Vicente Isaías

Estudio de Santiago Porter mostrando sus pinceles y materiales de pintura. Fotografía por © Vicente Isaías

VI: Did you manage at the beginning to create an image that convinced you?

SP: (laughs) Of course, the first thing that happened was that painting stopped me in my tracks, as we say here. It expelled me, it set limits. I feel that painting is very frustrating. My technical difficulties related to ignorance, let’s say, not mastering the craft, not mastering the possibilities, immediately made me fail miserably. It frustrated me deeply.

VI: Didn’t you feel at some point that the frustration made you think, “Okay, I’ll just stick to photography”?

SP: What happened to me was that I said, well, I have to learn. I mean, if I want to try it seriously, there are some things that I basically can’t not learn.

VI: And continuing to grow as an artist means that… Right?

SP: The truth is, I didn’t think about it in those terms. I mean, I didn’t imagine going back to photograph because I just didn’t have the desire to do it, right? I mean more like expanding on… perhaps what I had always wanted to do. I always worked very dogmatically within the possibilities that photography offered me and the certainties or exploration that I developed within photography in practical terms, but also intellectually. In some way, in painting, I proposed something completely different.

VI: I was reading on the plane on my way here a text about photography and abstraction, and the impossibility of representation itself. By transitioning to abstract painting, you opened up a whole Pandora’s box that allows you to explore this abstract, more ethereal language. It must be very interesting to have that possibility of representation just by changing the medium.

SP: Totally, it was everything to me. And it also happened that, as always happens when I started exploring a new medium, everything related to painting interested me and I no longer saw photography, I no longer read about photography, I no longer wrote about photography. At that time, painting was a whole new world.

VI: Having explored this profound transition, I want to ask you, Santiago, what makes an image moving for you?

SP: A moving image touches you almost spiritually.

VI: What are the conditions that you believe a photo achieves to do this? (pauses) Does it even have an answer?

SP: No. It doesn’t have one. It doesn’t have an answer because it’s deeply personal and has to do with each individual’s experience and processes. The absolute absence of the possibility of achieving that answer is, from my perspective, of course, what somehow compels us to stay, to keep doing, to keep trying in that tireless pursuit, like the carrot and the donkey.

VI: (laughs) A tireless and unattainable pursuit, the sublime.

SP: I think by its very nature of the image, we fall short of that possibility of an answer. It’s unattainable… to understand the why of [an] image that satisfies us. But in that tireless pursuit, we have no choice but to keep doing. The day that question ceases to be important, at least for me, will probably be the day I somehow abandon making art.

VI: How about we take a walk through your studio? It’s very tidy, are you always so methodical?

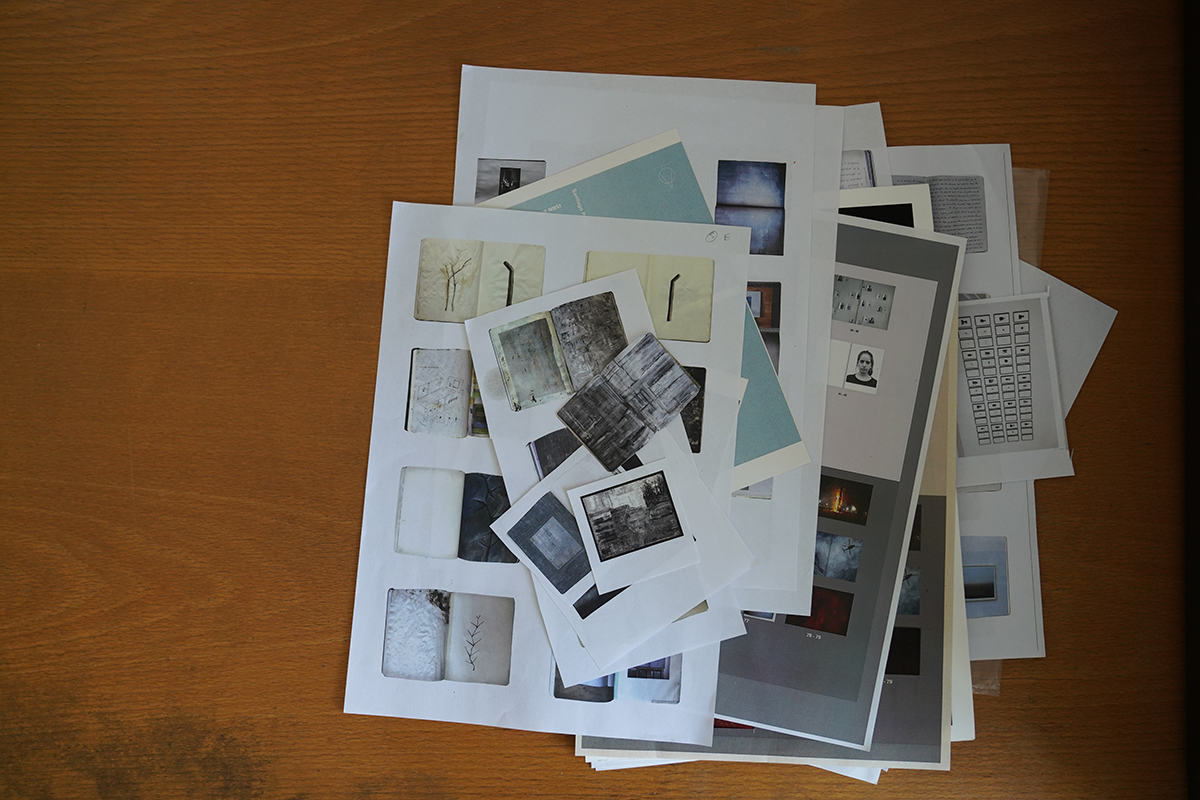

SP: I’ve been away for a few days. It’s been a few days since I painted, so it’s tidy. But generally, there are things on the walls that I’m working on, samples that come and go. There are many paintings, photos, all these things you see here are the works that are coming and going from the shows and ready to go out or have just returned. These are going to a show in Uruguay soon.

Santiago Porter’s office in his studio in Villa Crespo, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Photography by © Vicente Isaías

Santiago Porter’s working materials in his studio in Villa Crespo, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Photography by © Vicente Isaías

VI: I like the space because there are very distinct sections, right? Here is more about painting, here is more about archives…

SP: It’s because I know where things are, and I like them to be where I want them to be. Even so, things change according to what inspires me. Now, there’s a lot of text and personal photos. (points to the desk) The year ended, and it was a very particular year because I published a book of texts, Los Días Nublados, and at the same time that I worked on that book… It was the same time that I was accompanying my father’s illness process.

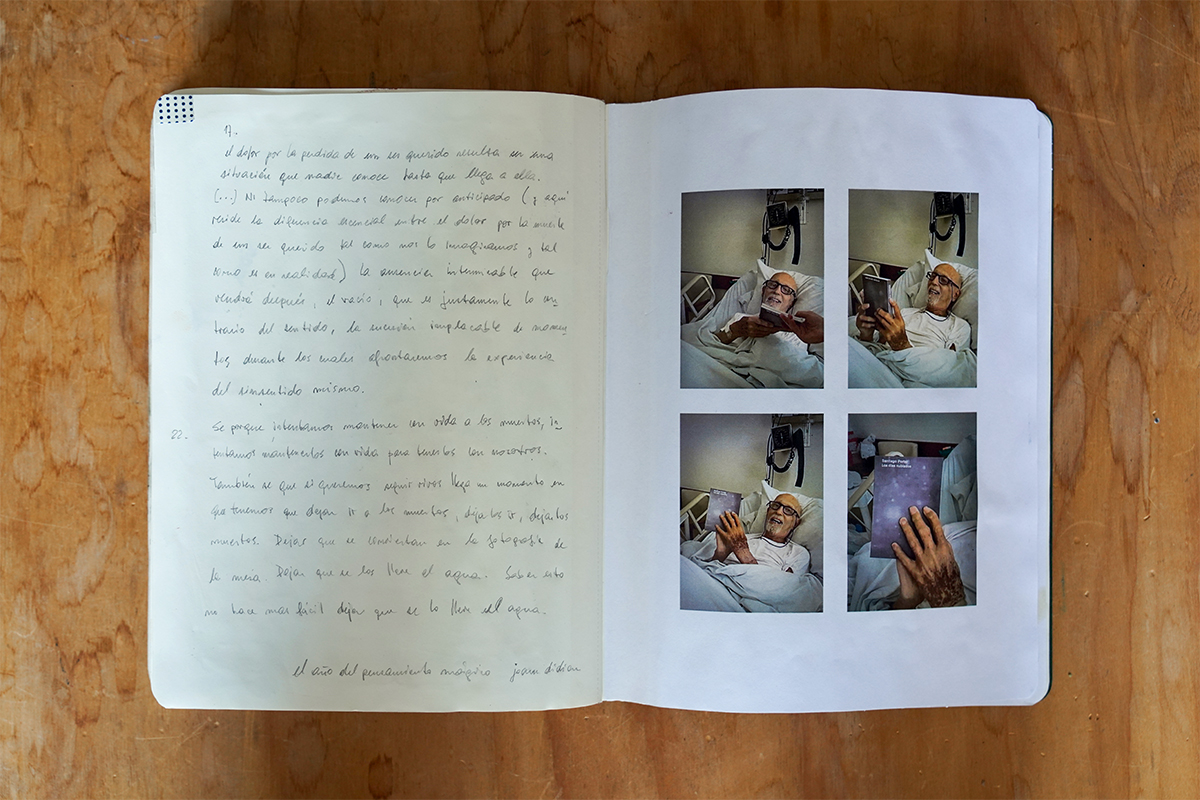

Final entries in Santiago Porter’s 2023 personal journal, dated December 2023, capture poignant moments of his father in the hospital, receiving Porter’s book “Los Días Nublados” in his final days. Photograph by © Vicente Isaías

VI: What happened?

SP: They diagnosed him with leukemia exactly a year ago. And the process, let’s say, also lasted exactly a whole year. The book Los Días Nublados also reproduces some pages from my work journals: things that I found and that went into the notebooks as a way to extend that bond that was somehow fading or coming to an end. He was a very close person, and towards the end, I slowly began to rescue archives and things related to my photography and my father. So, the last pages of last year’s journal are somewhat dedicated to the final stretch of my father’s illness’s compassion and accompanying him until saying goodbye.

VI: And these records that were left behind, do you plan to do anything with them?

SP: Yes, although everything concluded at the end of the year, there were still some shrapnel, that smoke left… Maybe something else will come out of it. Well, maybe… It’s impossible to truly know. What interests me, or what I like, or what serves me, is to keep working. It doesn’t matter what will happen with it, what it will become.

VI: That’s very good advice. We too often think we have to create with a purpose.

SP: You see, that was somehow given to me by my own experience, let’s say. To remain in the work, to inhabit the work. Sometimes that results in something that leaves the studio and deserves to be shared. Sometimes it’s the everyday work that leads you to a new project.

VI: I can’t wait to see what is born form the from the remnants of smoke left by your last project.

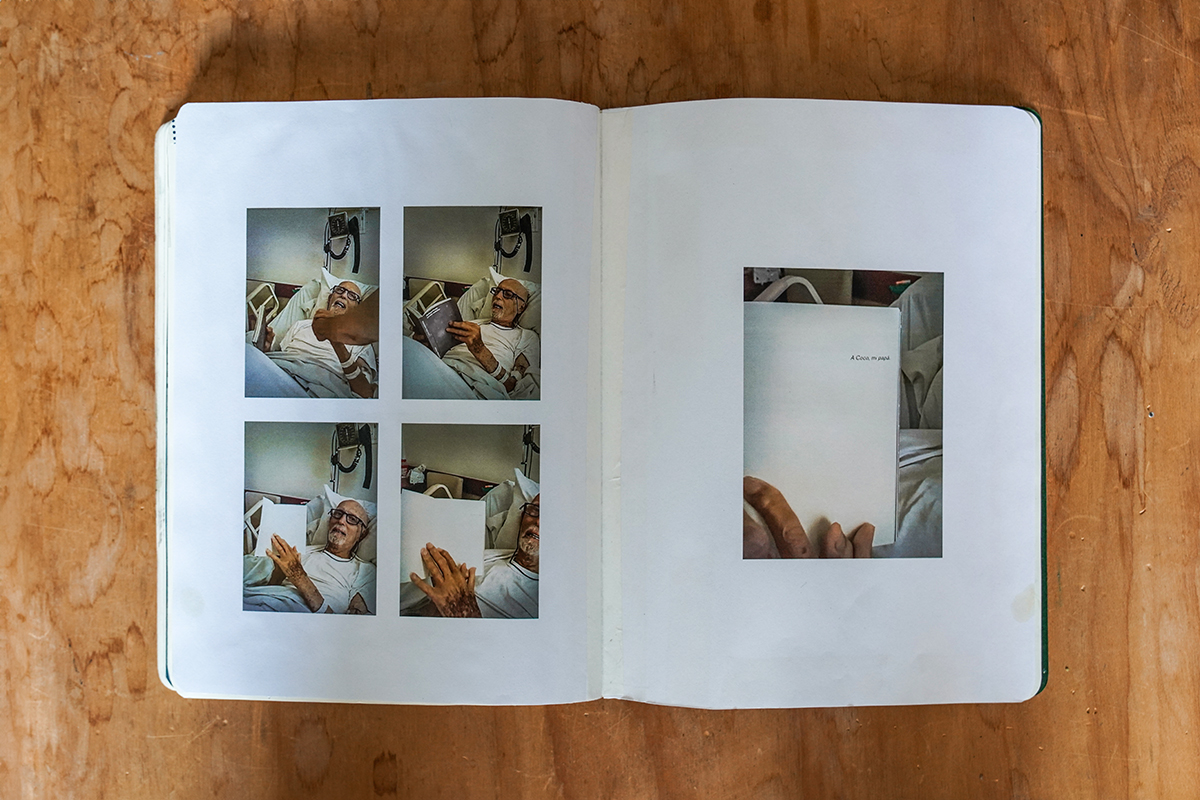

SP: I’ll show you now. To make this book, it was almost like a farewell, in some sort of way. This was the last push, the final moment we spoke. This is the last day of my father’s life and the last day we managed to get the book to him in time for him to see it. I showed it to him.

VI: He looks so happy and proud.

SP: Yes, totally. That’s my man. There he is pointing at his dedication on his book “To Coco, my father.” (pauses) He died the next day. And like we talked at the beginning today, that’s were the book ends, and my journal.

VI: Santiago, this is so touching. My father died of cancer, too. Thank you for opening up and sharing all of this.

Final entries in Santiago Porter’s 2023 personal journal, dated December 2023, capture poignant moments of his father in the hospital, receiving Porter’s book “Los Días Nublados” in his final days. Photograph by © Vicente Isaías

Vicente Isaías is a Chilean multimedia artist working primarily in research-based, staged photographic projects. Inspired by oral history, the aesthetics of picture riddle books, and political propaganda, his complex still lifes and tableaux arrangements seek to familiarize young audiences with his country’s history of political violence. His 2022 debut series “JUVENILIA” earned him an Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the Saint Botolph Club Foundation, a Lenscratch Student Prize, an Atlanta Celebrates Photography Equity Scholarship, and a photography jurying position at the 2023 Alliance for Young Artists & Writers’ Scholastic Art and Writing Awards in the Massachusetts region. His work has been exhibited most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally in print and digital publications. A cultural worker, he has interviewed renowned artists and curators and directed several multimedia projects across various museum platforms and art publications. He is currently a content editor at Lenscratch Photography Daily and Lead Content Creator at the Griffin Museum of Photography. He holds a BA in Studio Art from Brandeis University, where he received a Deborah Josepha Cohen Memorial Award in Fine Arts and a Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography.

Follow Vicente Cayuela on Instagram: @vicente.isaias.art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026