Catching up with Karen Navarro: On the Politics of Visibility, Motherhood, and Public Art

Karen Navarro, currently based in Houston, is an Argentinian artist of Mapuche, Guaraní and European descent who works across the mediums of photography, collage, and sculpture. Her work investigates the intersections of identity, representation, race, and belonging in reference to her migrant experience, her Indigenous identity and the history of colonization and its influence. Navarro is interested in the nuances of identity, the constant hybridization of cultures, communication technologies and the concept of beauty—aiming to create, through her work, space for acceptance and existence. Navarro has won the Artadia Fellowship, the Top Ten Lensculture Critics’ Choice Award, and the Houston Center for Photography Beth Block Honoraria among others. And, in 2024 she was artist-in-residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, New Smyrna Beach, FL. Her work has been exhibited in the US and abroad. Selected shows include Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH); Artpace, San Antonio; Galerija Upuluh, Zagreb, Croatia; George Washington Carver Museum, Austin, TX; FAR Center for Contemporary Arts, Bloomington, IN; Holocaust Museum Houston; and Melkweg Expo, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Additionally, Navarro’s work has been featured in numerous publications, including ARTnews, The Guardian, Observer, and Rolling Stone Italia.

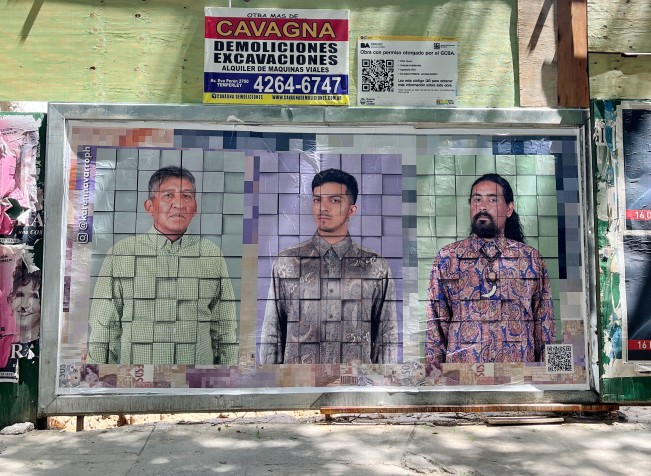

VI: Karen, it’s a pleasure to have you here. After some time, you return to Buenos Aires to exhibit El Lado Oculto de la Luna (The Hidden Side of the Moon) in a public art format. What does this return to Argentina and the presentation of this work focused on visual identity and the visibility of Indigenous communities represent for you?

KN: For me, it was very emotional to return to Argentina to present a work of such personal and social importance. I consider the conversation about the visibility of Indigenous communities to be an ongoing one and a historic debt in Argentina. Being able to return and show these faces, celebrate them, and occupy public spaces … which are generally not inhabited … by Indigenous men or women was very exciting. I strategically chose to display the works in neighborhoods that belong to a specific economic sector typically occupied by the white Argentine population to make a statement about occupation and visibility, to occupy those spaces in which … even when I was in Argentina, I didn’t feel like I belonged to the city.

VI: I am surprised by the strategy behind the choice of those locations. It goes deeper into the intention of your work beyond just visibility. From your perspective as a diasporic artist, could you expand on the duality of exhibiting your work both in Houston and in Argentina?

KN: Before bringing the work to Argentina, it was presented in Houston through over 100 digital screens across the city, and starting tomorrow, the same project will be presented as an installation coinciding with FotoFest. For me, it was crucial to show those Latino faces in the United States, where interpretations of identity can significantly diverge. It was important for me to bring those faces to the United States because they are faces from Latin America that, although they are… “determined” or “marked,” many nuances of these identities are interpreted differently here in the United States, how can I say it…

VI: Generalized?

KN: Yes, and not only that, but racism exists in a subtle way in Argentina as well, but it exists. My intention was also to highlight that, despite perceptions of colorism and subtle racism… these differences and cultural particularities are crucial. Bringing this conversation to the United States to show identity and to show that these small differences, details, and particularities exist was also a way for me to bring visibility to the reality of other places. As someone said to me, “we are café con leche (coffee and milk), racism doesn’t exist.” I think it’s a very important conversation because it’s not as simple as “it’s settled, it’s black or white.”

© Karen Navarro, from El Lado Oculto de la Luna, public intervention, Oak & San Felipe, IKE, Houston, Texas

VI: Absolutely, considering the current media discourse in Argentina… I was reading some articles from Mapuche social leaders in Argentina who consider that Milei represents the return of a discourse of white hegemony in politics that poses a danger to Indigenous realities. What do you think about this transition?

KN: [When] the elections were won by Milei, it was a very delicate moment. It was a moment where I didn’t know what was going to happen, many people were afraid. In the end, I ended up postponing my trip to Argentina. It had been a year since I took the photos in September, and I finally decided to go in January and just then the election happened. That’s another thing that seemed almost coincidental to me. At that moment, I also questioned what is the importance and my role in this. What authority do I have to come from outside to present a work at a moment when such gesture of kindness can be misinterpreted as naive, right? But then I thought and I said, in these moments it is more important than ever to visualize, it is more important than ever to generate dialogue and open up to conversation on these issues of visibility and the rights of Indigenous peoples.

VI: Absolutely. And going back a bit in time, to give more context to the people who will read this, you first returned to Argentina to photograph, specifically here for this series, and then you returned when it was going to be installed in public spaces.

KN: Yes, that’s exactly how it was. I opened an open call and with the help of Eugenia Anahí Figueroa, who is a Kolla Indigenous activist from Northern Argentina, living in Mendoza, she gave me a hand. I opened the call and many people applied. I went to take photos. Then I came back, I felt that I needed time to move with a lot of respect, to know what I wanted to express with these images. Another thing that I was thinking a lot about is regarding extractivism. I didn’t want to go, take more photos, turn them into an object, and then sell them. So that’s why a lot of digitization and presentation, as a temporary model. The same with the installation I’m doing here in Houston. It’s an installation, but there’s no actual work yet, there’s no material element because it didn’t seem right to me, it didn’t sit well with me. This idea is working on such a delicate issue, it’s fighting against it. It was a process of respect and deep reflection, especially on how to present these images without falling into cultural extractivism. The temporality and digitization of the works were conscious decisions to avoid insensitive commercialization of the work.

VI: Considering your previous sculptural works, I am struck by and pleased with this new ethical consideration. You financed your return to Argentina through a series of jobs. Could you delve into that?

KN: It was essential to communicate a message through my art, one that constantly reflects my heritage and perspective. The use of specific objects, such as textiles and Mapuche coins, aims to make direct connections with my culture and criticize colonial dynamics. The blending of cultures, hybridization. For this project, I was thinking of a work that was for me, for my home, to contemplate daily. For me, it’s like a mirror, you know? And also like a… How do you say it when… it’s not a mantra…

VI: An affirmation?

KN: Exactly.

VI: I’m pleased that you mention the word “mirror” as well because the last time we interviewed, we talked about obsidian and its reflective qualities, as well as its significance for Indigenous communities.

“The obsidian stones take on various meanings and have been vastly used by ancient peoples from the Americas to make weapons, implements, tools, ornaments, and mirrors. I was particularly inspired by its use as a mirror and its meaning. Aztecs believed that by gazing into an obsidian mirror, sorcerers traveled to the world of gods and ancestors. Metaphorically, the mirror catches my reflection and includes me among them. I’m no longer the “other,” I’m part of it all. Somos Millones (we are millions) makes reference to the population number of Indigenous peoples, specifically Mapuche, in Argentina and Chile.”

VI: It’s good to see how you’ve become even more specific, establishing these direct links that led you to choose this particular object. Additionally, you’re now exploring your Mapuche heritage further with the theme of textiles and coins.

KN: Thank you. Coins have always been objects of interest. This element is a kind of headband that women use to enhance their beauty. I like to explore the idea of the space I inhabit, not only as a woman, immigrant, and Indigenous descendant, but also as European. There’s a space where I’m not completely one thing or the other, where I don’t fully fit into any of those identities. In addition to coins, I was intrigued by the symbolism of the “guarda pampa,” and the floral motif inspired me from the aprons of Mapuche women. There’s irony in how these stories are reversed: the floral ornaments that Mapuche women use on their aprons are not original; they were adopted after European colonization. Europeans incorporated elements of Mapuche culture and made them part of their clothing. On the other hand, the “guarda pampa,” of Mapuche origin, was adopted by Argentine cowboys (gauchos).

VI: This is so fascinating!

KN: Mate is another interesting example.

VI: How so?

KN: Not everyone knows that mate is Guarani.

VI: Really?

KN: Yes, it is. And it’s also an aspect I want to investigate more in the future.

VI: I’m very interested in this convergence of cultures and how it represents this Latin American mix, as well as what it means to be Latino. It’s fascinating to observe how all these identities are constructed from cultural hybridizations over the centuries. It’s especially interesting to learn about the specific history of the objects you’ve selected and to contextualize them in this postcolonial environment.

KN: Absolutely. I’m also using textiles like the Aguayo.

VI: How beautiful. Andean, Aymara, right?

KN: Yes, Aymara from the North.

VI: Any other materials you are working with?

KN: I’m also working with other textiles, such as floral textiles and the belts of the gauchos that come from Mapuche culture. I’m preparing all of this for an installation, something similar to braids, although not as large, but I’m very excited about everything I’m working on. This idea started during a residency at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, which has me very excited.

VI: Now, on a different note, I’d like to finish our interview with the breaking news: you’re pregnant! Congratulations!

KN: Yes, thank you! (smiles)

VI: How far along are you?

KN: Five months. One week, five months.

VI: Especially now that you’re expecting a baby, has your way of viewing your own artistic work changed over the years? How has it impacted your artistic endeavors?

KN: In part, yes. For example, I’m now working on a series of images documenting the pregnancy. I’m exploring the relationship between these images and the European canon, referencing works by Albacete and Botticelli’s Venus, and others. Additionally, I’m delving into self-portraiture for the first time, reflecting on myself and my future daughter. I’m not only thinking in terms of acceptance but also the power she will feel coming from roots that make her strong. I want her to know that she has ancestors who have suffered and that because of that, today she carries in her veins part of that Indigenous blood that connects her to the land.

VI: What a crossroads, right? Last time, you spoke a bit about finding yourself, finding your identity and your sense of belonging by portraying other people who represented that liminal identity experience you had. Now I feel like all of that is converging towards looking inward, especially with the self-portrait.

KN: Art is a very, very interesting journey. It takes you in different directions that ultimately always end up this personal quest of what one desires so much in this life — to answer those questions that don’t have the answers to.

VI: I think it’s beautiful that you are handing her this system of security and affirmation so she has a strong sense of who she is.

KN: Absolutely. In thinking about this, I also consider my daughter as a legacy. I wonder what message I want to convey to her, a message that I didn’t have while growing up. I was always raised with the idea of the white beauty canon, which didn’t fit me and always left me on the sidelines. Now, I want my daughter to know that her identity is valid and powerful.

References:

1. Roberto Muñoz. 2022. “¿Qué Hacemos Con Los ‘Indios’?” en El Aromo, Vía Socialista, Nueva época. Año I, nº 2., Junio 2022, ISSN 1851-1813.

2. Roberto Muñoz, 2022. Ibid.

3. Carlos Alfredo Müller “La Agricultura De Los Nadies.” 2024. IADE. March 21, 2024. https://www.iade.org.ar/noticias/la-agricultura-de-los-nadies.

4. Carlos Alfredo Müller “La Agricultura De Los Nadies,” Ibid.

Editor’s note: This article has been translated from its original version in Spanish. This article was modified on March 29 to correct punctuation, capitalization, and reference errors.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026