Michael Borowski: Azurest

This week we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our last call-for-entries–way back in late-2022 (a new call will be going out sometime in the near future, so stay tuned for details…). Today we are viewing and hearing more about Azurest by Michael Borowski.

Michael Borowski is an artist and educator based in Blacksburg, Virginia. He received an MFA from the University of Michigan and a BFA from the University of New Mexico. He works with an expanded photographic practice to examine queer space and belonging. By combining aspects of fact and fabrication, documentary and science fiction, Borowski constructs histories that were undocumented or actively repressed. His work has been exhibited in national and international venues including Candela Gallery, Virginia; Soho Photo Gallery, New York; Site:Brooklyn Gallery, New York; The Colorado Photographic Arts Center, Colorado; the Prairie Center for the Arts, Illinois; the Czong Institute of Contemporary Art, Korea; and Espace Projet, Canada. He was awarded a fellowship from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts for 2022-23, and a grant from The Graham Foundation in 2019. He is currently an Associate Professor at Virginia Tech.

Follow Michael on Instagram: @mdborowski

Azurest

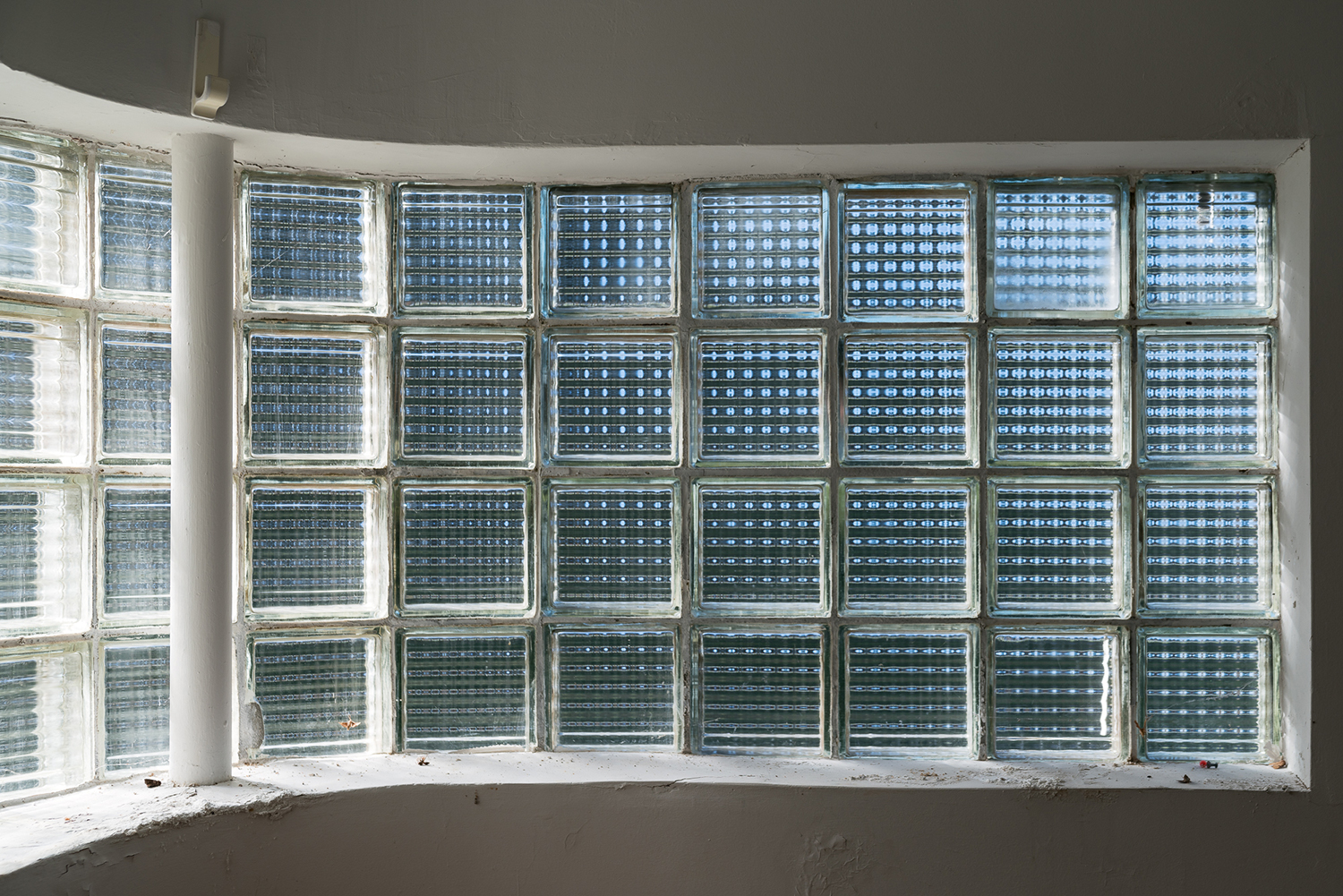

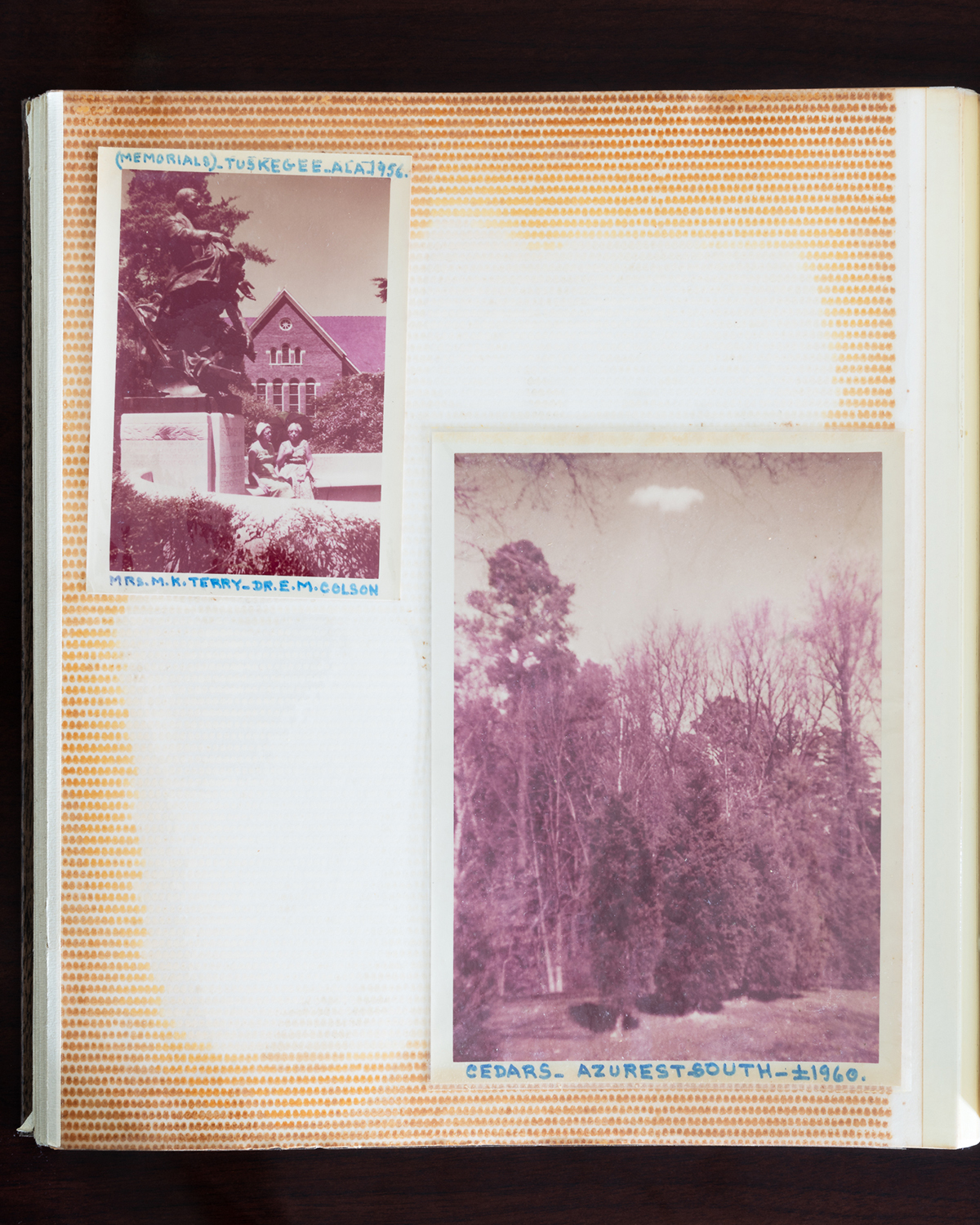

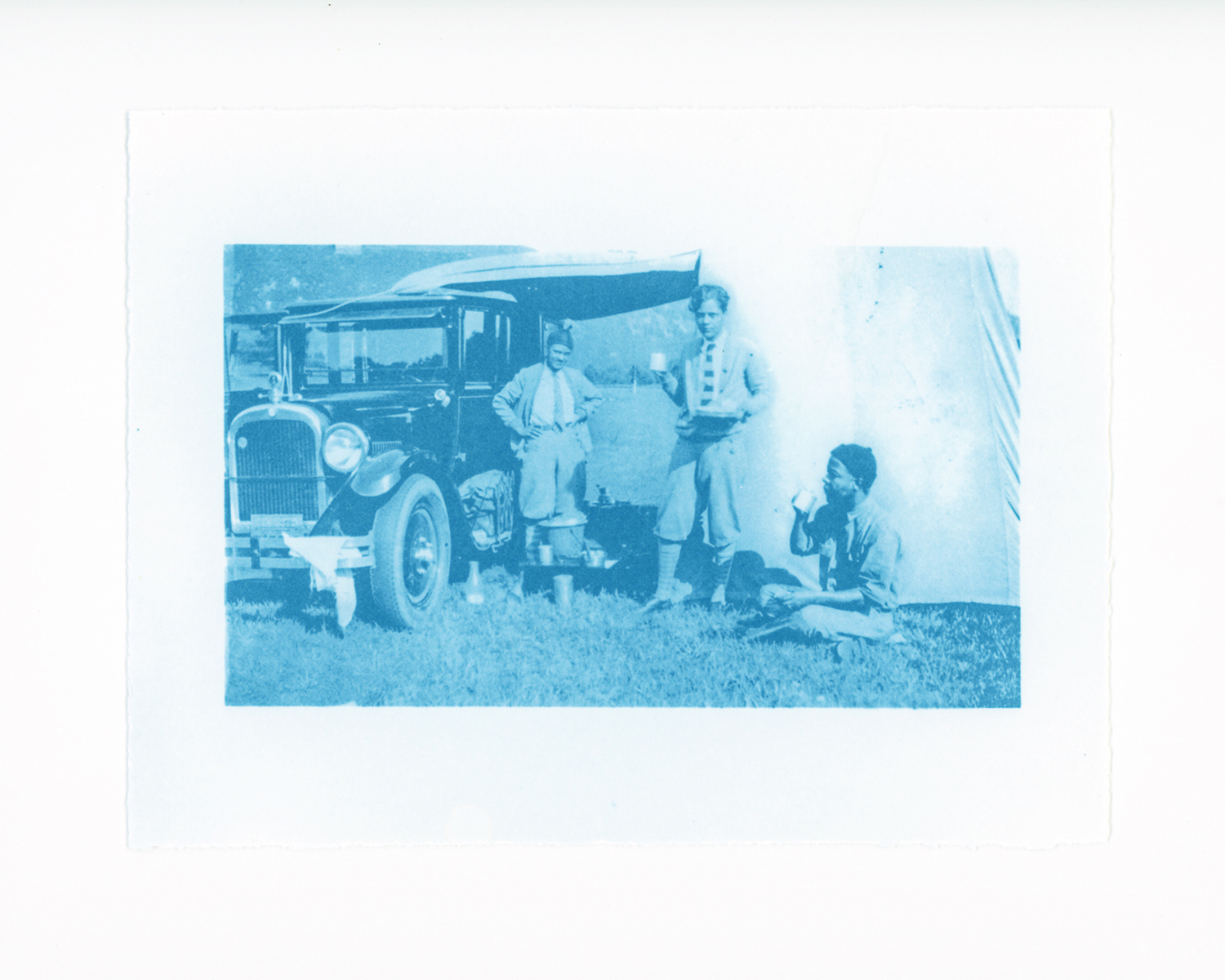

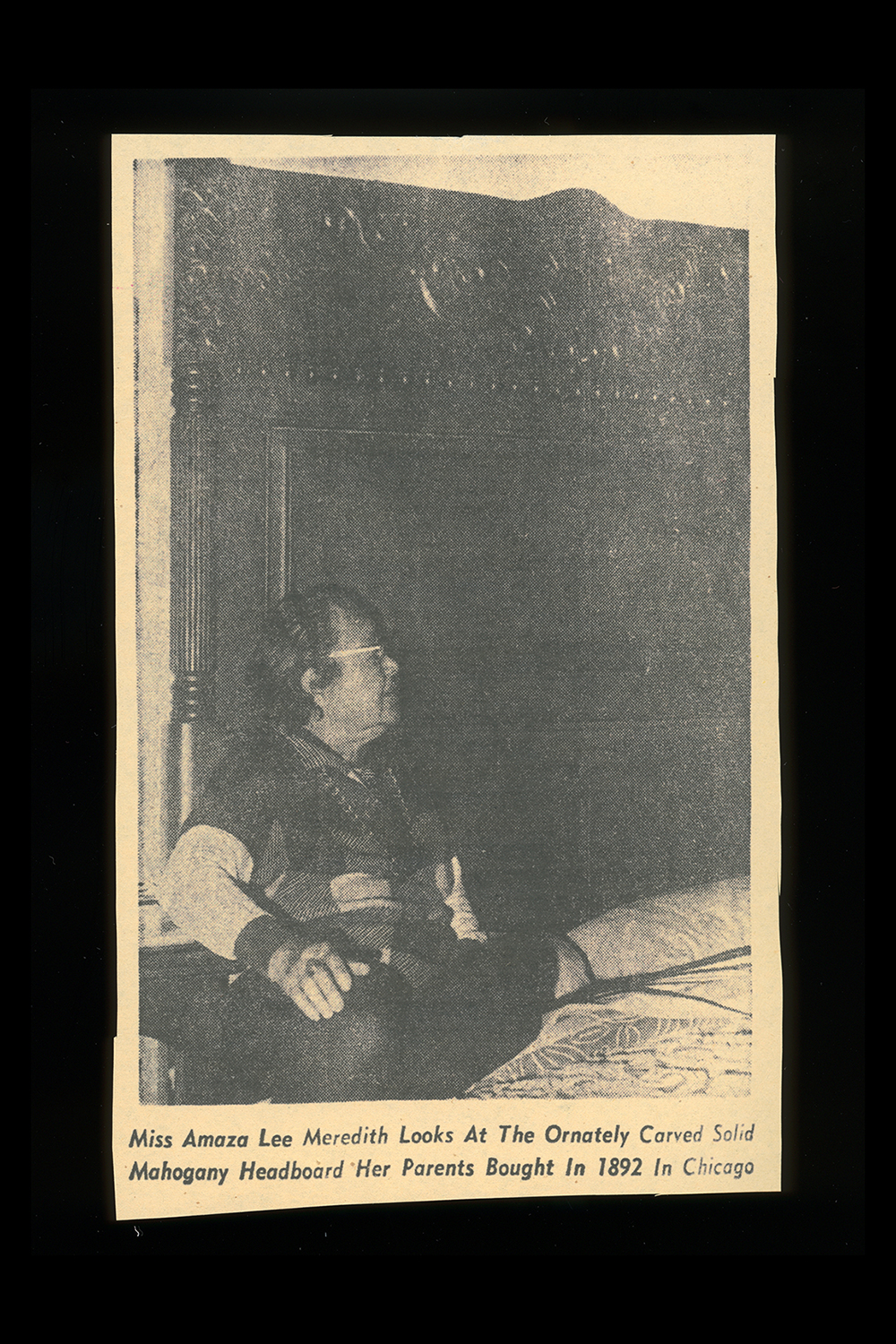

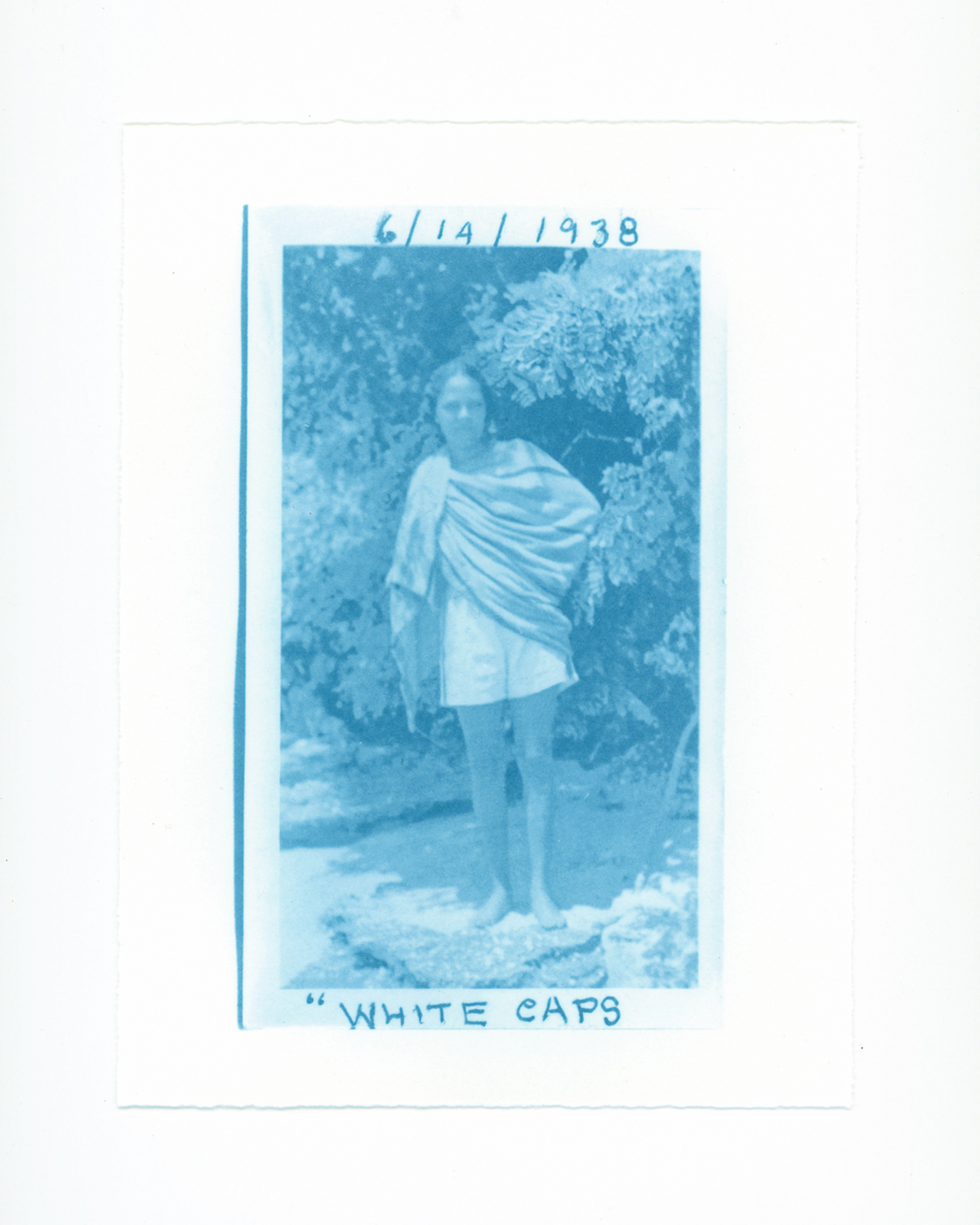

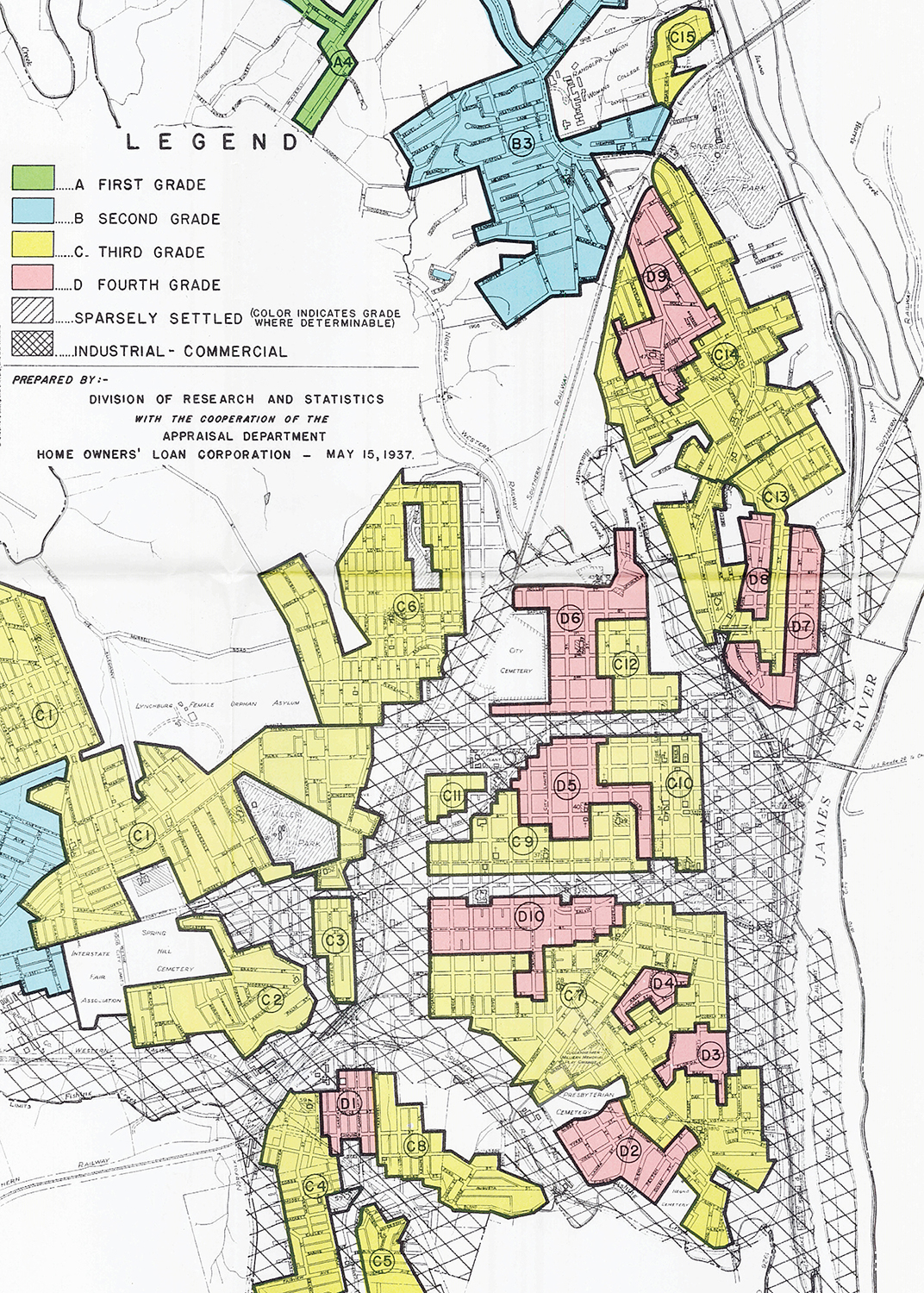

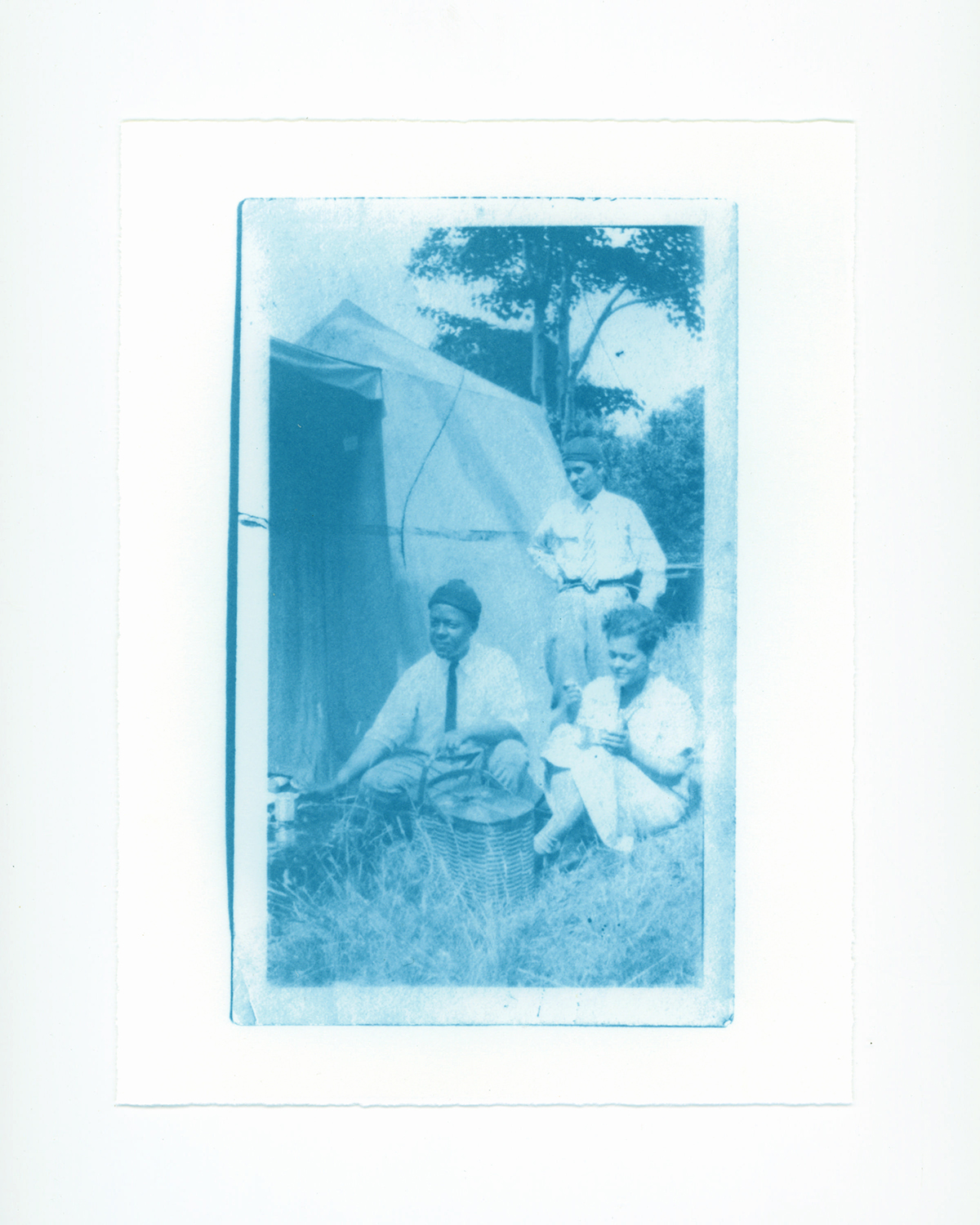

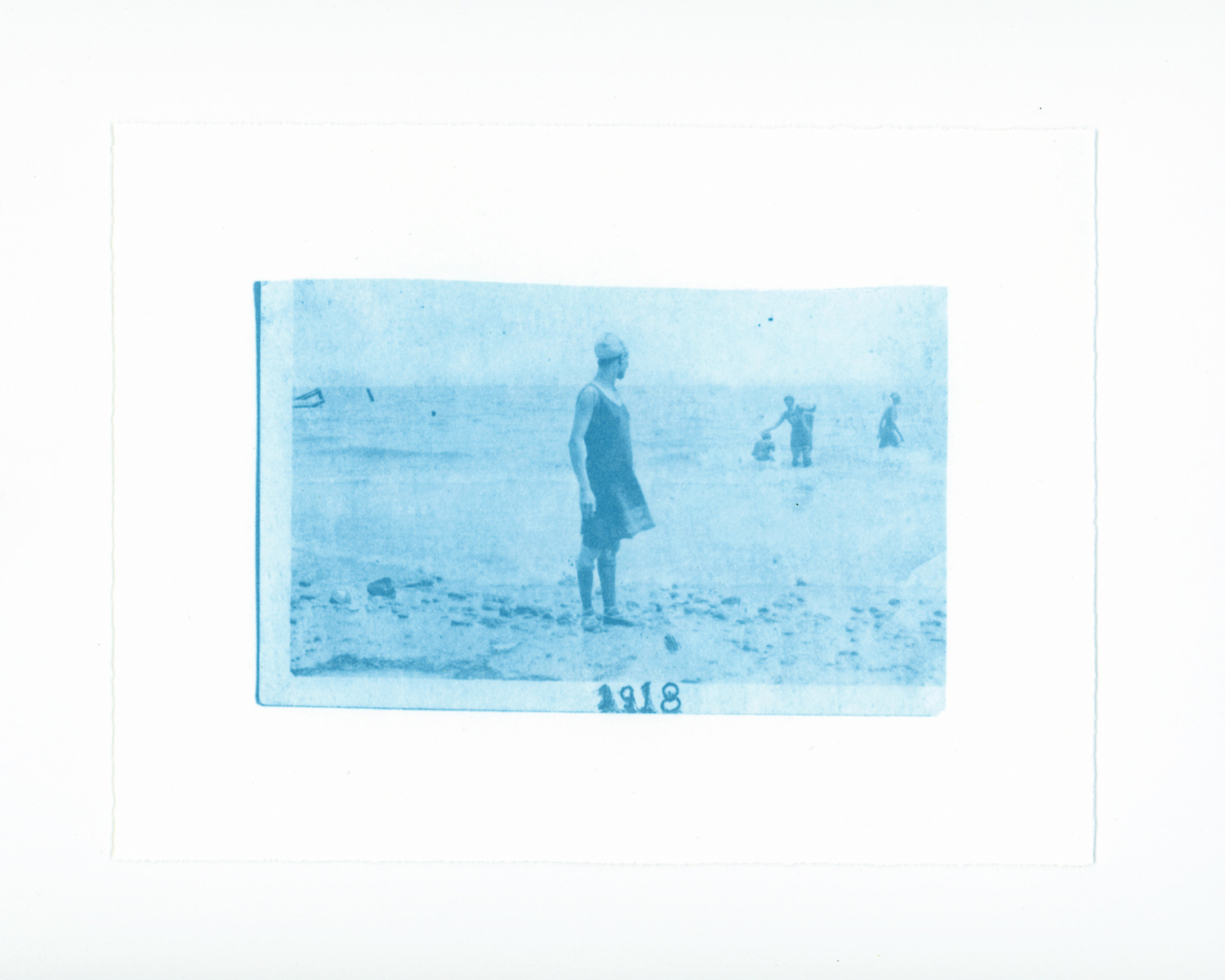

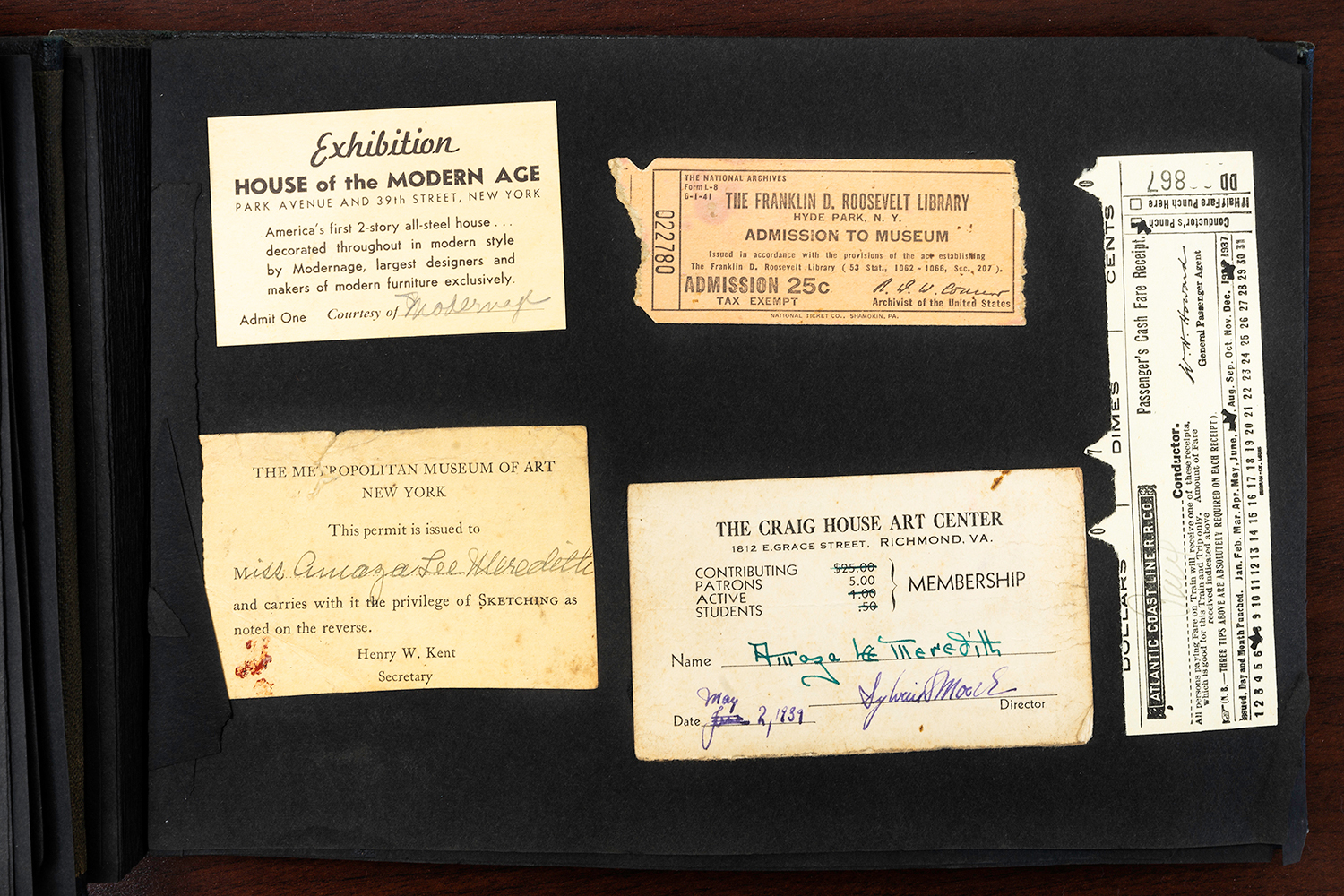

Azurest is a series of photographs exploring race, gender, queer desire, and design in Jim Crow era Virginia. It is part documentary and part speculation. The subject of the series is Azurest South, a 1938 International Style home designed by the underrecognized African American architect Amaza Lee Meredith. Even though she was barred from the architecture profession at the time due to her race and gender, Meredith designed and built this home for herself and her partner Dr. Edna Colson. This series combines photographs of the historic home with documented ephemera from Meredith’s archive. The color blue is prominent in the building and echoed in cyanotypes made from Meredith’s personal photographs showing travel and recreation. This constellation of imagery situates Merediths’ life and home within broader context of modern architecture and race, gender, sexuality, and housing in early 20th Century America. This project was made with the support of a 2019 grant from the Graham Foundation.

Daniel George: What brought about your interest in Azurest South, leading you to create this work?

Michael Borowski: Meredith was an architect, artist, and educator born in Lynchburg, VA in 1895. At that time there were no prospects for a Black woman to work as an architect, so she studied art at Virginia State University. She continued her studies at Colombia Teachers College in New York City, before returning to Virginia State to teach. In 1938 she designed and built a home on campus, where she lived with her partner Dr. Edna Mead Colson. The home is designed in the International Style, demonstrating Meredith’s knowledge of contemporary architectural discourse. At the time in Virginia, this style of modernist building was extremely rare.

I can’t recall exactly where I first heard about Azurest South. I think it was a podcast or YouTube video referencing Mario Gooden’s book Dark Space: Architecture, Representation, Black Identity. Gooden wrote a chapter about Meredith and Azurest South. It was around the time I moved to Virginia, maybe 2016 or 2017. Whenever I move to a new place I read about it. I am particularly interested in history and the built environment, so those stories jumped out for me. It was just one of those stories that caught my attention and every so often I would come back to it and try to learn more. I read Gooden’s book and dug up whatever I could find on the Internet. There were a handful of places that had written about Azurest South, but the same paragraph or two seemed to be repeated. Meredith’s life sounded like such a rich story, but there wasn’t a lot written about it.

VSU is about a three and a half hour drive from Blacksburg, so for the first few years I just read about the building without ever seeing it in person. Eventually I called to see if I could set up a visit to photograph the home. The home was left to VSU as part of Meredith and Colson’s estate, and is managed by the VSU Alumni Association. They were very relaxed about me visiting. A woman met me on campus and unlocked the house. I had as much time as I wanted to explore and photograph. Before that visit most of the images I had seen were of the exterior. Seeing some of the rooms inside was incredible. Especially her use of color. I think that sets Meredith’s home apart from other International Style buildings. The original bathroom has bright yellow and black tile. There was a mechanical room painted azure blue. I almost left the house without opening that door. It was a powerful experience. After that I felt committed to making work about Meredith and her home.

DG: Would you elaborate on the idea of this work being “part documentary and part speculation?” Why was it important that you explore these things that “were not, or could not be, recorded?”

MB: I like to joke that I have a love/hate relationship with photography. When I started graduate school at the University of Michigan I was set on not making photographs at all. I was interested in sculpture and installation. I made these mobile, collapsible furniture pieces. But I wanted them to read as speculative design rather than sculpture, so I photographed them in situations in the real world. I was thinking of Robert Smithson’s “site/non-site” relationship to land art. The furniture pieces existed in the real world, but they could also be experienced in the gallery through photographs. And I have always been interested in the fact that, despite knowing that photographs are staged, manipulated, and constructed, we still understand them as representations of the “real world.” I don’t think it is a contradiction. We can understand both of those things being true. So my work in graduate school got me interested in the theme of fabrication, both in creating furniture and the constructed photograph.

When I started making work about queer history I realized that, especially pre-Stonewall, there were almost no official historical records. For long periods of time, homosexual acts were illegal, so the only official records would be criminal records. It was safer to remain invisible. When I first started to research Amaza Lee Meredith, there wasn’t much explicitly saying that she was queer. It was one of those “they were roommates for their entire lives” situations. It was clear that she never used the term “lesbian” or any explicit language about her relationship to the woman she lived with for the remained or her life at Azurest South.

I talked with historians writing about other women architects of that time, who lived alone or with another woman but never claimed to be gay. They were frustrated that they couldn’t say these were queer women because of limited evidence. Eventually I had to remind myself that I’m not a historian. I’m not a journalist. I’m an artist and I can make work based on feelings and imagination. That realization reminded me of my work in graduate school. I came back to those terms “fabrication” and “speculative” but now applied to queer history. I think Zoe Leonard got to the heart of this with The Fae Richards Photo Archive project. She created a series of photographs that document the life of a fictional black lesbian actress. It includes film stills, family photos, and other ephemera all staged and styled to look like they were from the Civil Rights era. Leonard gives clues that reveal the project’s artifice. Even though this story if fictional, it lets us imagine the existence of similar stories that went undocumented due to bigotry and racism.

DG: Tell us about your use of Amaza Lee Meredith’s cyanotypes, and the significance of interspersing these photographs within your own.

MB: I came up with using cyanotypes after my initial visit to Azurest South. The photographs of Azurest South were beautiful architectural photographs, but I was so inspired by her life and story. Every time I shared the work with people, I would have to explain all the biographical backstory. None of that came through in the photographs of her home. So about six months later I went back to VSU to visit the Special Collections Library, which holds Meredith’s archive. I spent a day looking through her personal photo albums and sketchbooks. I photographed a lot of material without knowing what I would do with them. Her personal snapshots seemed to convey her life, particularly her travels and community. I wanted to include these in the series but altered in some way. I guess I was thinking about the color azure, the mechanical room that I almost missed. There was also a painted blue trim around the roof of Azurest South. I thought cyanotypes could reference those particular shades of blue. Also, Meredith was an architect and cyanotypes were the first blueprints. I actually photographed a few blueprints in her archive, but I didn’t end up recreating those. I liked translating the photos into a slightly different medium. There were actually quite a few steps. I started with the photographs of the scrapbooks in the archive, then cropped the image down to just the individual photograph and removed the backgrounds. Then I made digital negatives from those and printed them as cyanotypes. They are printed to scale, so much smaller than the photographs I took. I wanted to make a clear contrast between images of the home currently and images of her life in early 20th Century. Printing them as cyanotypes made them feel more like a dream or a memory than an archival document.

DG: Speaking more broadly about your creative practice (and perhaps specifically to this project, as well), what prompts you to examine repressed histories through “architecture, technology, and the environment?”

MB: I think “place” has always been a core source of inspiration for me. Whenever I moved somewhere new, I have to recalibrate my work. I think of my art practice as my way of finding my place in the world, and often specifically the place where I live. I also believe that design is a reflection of culture. We can understand how society operates based on the built environment. I love things like Atlas Obscura and 99% Invisible. Learning about the history of a place often gives me ideas for new work.

My interest in repressed histories really picked up over the past 6 years or so. My move to Virginia landed me in the most remote, rural place I had ever lived. It was also the most verdant. Normally I would go on walks around town with my camera, but instead I was going on hikes. I had to learn how to make interesting compositions in a dense forest. I’m still working on that! This was also my first time living in the South. Any study of the built environment in Virginia leads back to the Confederacy, and before that colonization. So I was struggling with very different environments to photograph and a fraught history. My usual question of finding my own sense of belonging led to a broader question of how many marginalized people could find belonging here. Finding stories in history helped. When I learned how historically marginalized people had organized or challenged the status quo, I felt more at home in the present. Meredith’s story was one of the first that gave me that hope. I wanted to share her story and maybe a similar feeling with others.

DG: What do you feel your photographs contribute to Amaza Lee Meredith’s legacy?

MB: I am really excited to see that more people are becoming aware of Amaza Lee Meredith and her work. I think all of our fields of study are taking a closer look at biases and whose work has been ignored for far too long. I usually approach a body of work imagining it being ultimately framed and exhibited. This work has grown in a different direction. There have been more people writing books and designing websites rethinking the canon of architecture who have asked to include my photographs of Azurest South. The photos were included in the book The Women Who Changed Architecture (Princeton Architectural Press, 2022) and a website called Pioneering Women of American Architecture. Like a lot of artists, I am used to working alone in my studio or out taking photographs. I haven’t done a lot of collaborative projects. This wasn’t an intentional collaboration, but it feels like many people are working together to share Meredith’s story. And I can see how much more reach something can have when many people are working on it.

I think what my work contributes successfully to Meredith’s legacy is providing an updated look at her home, using the skills I have as a photographer. Hopefully they express the inspiration and hope I felt from learning about her work. On their own, the work is making small ripples. I have exhibited them and presented the work at conferences. But I think there is a bigger impact alongside the work of architects, historians, and writers who want Meredith to be recognized for her remarkable life and achievements.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026