Andrés Pérez: Dead Family / Dead Homeland

This week on Lenscratch we present an eclectic survey of photo-based artists exploring issues of Queer identity and representation. These exceptional artists expand our appreciation for diverse photographic techniques, directing our attention to critical issues of bodily autonomy, reclamation, and belonging.

Today, our focus is on Venezuelan photographer Andrés Pérez.

An interview with the artist follows.

Dead Family

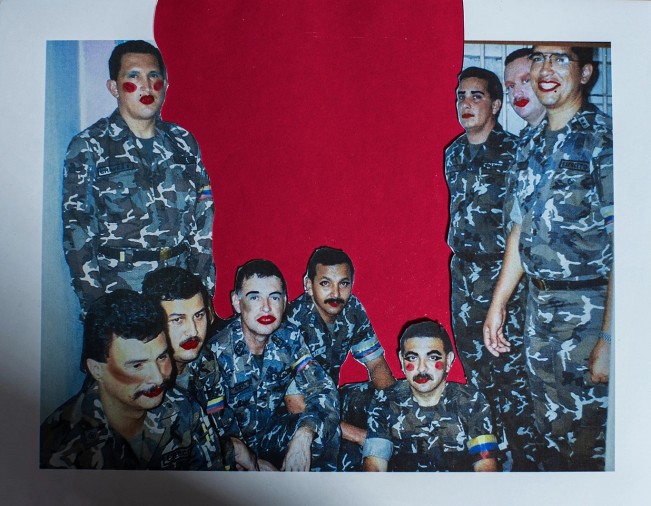

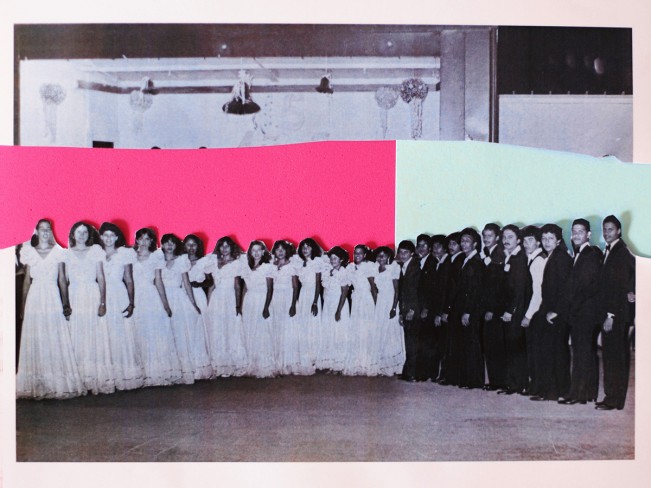

Dead Family is an investigation that views the family archive as a binary historical document that upholds heteronormative narratives imposed by patriarchal structures. These impositions perpetuate a sexist order that separates the masculine from the feminine and marginalizes identities outside of this political-biological mechanism. Diverse identities lack visibility in the act of “family portraiture.” Dead Family is a project that intervenes in the family archive. It is a photographic intervention, but also a political one. It is a naturally collaborative project that relies on the voices and perspectives of our community. This collaborative nature allows each individual to intervene in their own archives based on the premise: What would a more diverse visual memory look like for the future?

Dead Homeland

How many stories are unfolding

while ours is happening?

1992. A failed coup d’état.

1993. I was born, kicking in my mother’s womb.

1995. We made history with the fourth crown and

Venezuela became a universe.

1999. The arrival of a future dictatorship

and a new century.

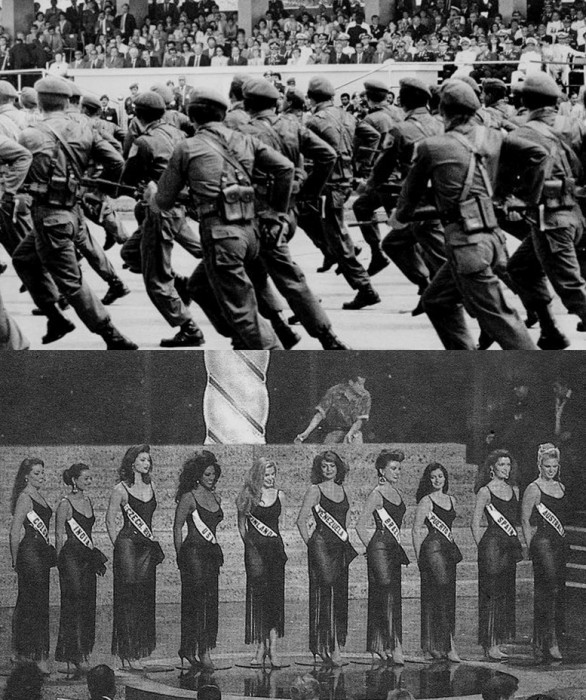

Gunshots. Crowns. Soldiers. Misses.

The weight of a woman cannot be equal to the weight of a man. What weighs more?

A family watching on TV political violence and simultaneously the opening of Miss Venezuela.

A militarized society, sometimes with guns, sometimes with heels.

Growing up amid these military stereotypes reinforced the binary regime and the culture of violence.

Dead Homeland revisits history to understand militarization and its dominant power.

Venezuela is the second country with the most Miss Universe crowns and currently leads among the 32 countries in the world living under a dictatorial regime.

Andrés Pérez (Guarenas, Miranda, Venezuela, 1993) is a non-binary photographer, visual artist and teacher. His studies in art and cinema, at the Universidad Central de Venezuela, gave him a sensibility for the image. In 2019 they migrated to Bogota-Colombia and this trip coincided with the decision to start their photographic career. As a diverse and migrant person, their work focuses on gender, identity, memory, binary violence and queer bodies, especially in Latin American territory. They address other themes related to the anti-patriarchal narrative and the deconstruction of the heteronormative with the interest of preserving a more diverse memory. As storytellers, they not only have the need to narrate about others, they are also interested in speaking from an intimate and autobiographical place. His photographic languages are portraiture, documentary narratives, fashion and expanded photography. This visual hybrid is the result of the union between his creativity and political interests. In 2023 the project Dead Family was the winning story of Pride Photo and was recognized in Picture Of the Year Latam in the category “re-signifying archives”. They won a Prince Claus Seed Awards in 2023. Exhibited in Paris, Amsterdam, Germany, Norway, Slovenia, Malaysia, Argentina, Colombia and Venezuela. Published in: Der Greif, Vist Projects, Lenscratch, Foto Femme United, Canon Latam, DW Español, Organización Nelson Garrido, Cinco 8 y El Universal.

Follow Andrés Pérez on Instagram: @le_veneque

Vicente Isaías: In your work, you explore the invisibilization of queer identities in the family archive, understanding “the archive” as a construction that reflects political and cultural beliefs entrenched in society. More recently, your project Dead Homeland generates a symbolic-aesthetic nexus between the culture of beauty pageants and the history of militarization in Latin America. Where does this idea come from, and how did growing up in such a turbulent decade as the ’90s in Venezuela influence your art?

Andres Pérez: The ’90s were a very important decade in Venezuela, as it marked the country’s paradigmatic and political change. Dead Homeland focuses on addressing binary violence through two archetypes that feed into the heteronormative vision and legitimize that binary filter that regulates bodies in Venezuela, but also regulates normativity in Latin America: the military archetype and the beauty queen.

I was born in ’93. A year before I was born, there was a coup d’état against then-president Carlos Andrés Pérez, led by the revolutionary Bolivarian commander, Hugo Chávez.

Years later, almost at the end of the decade, Chávez managed to enter the government, this time through presidential elections, and the left was installed in ’99. That promise of sovereignty installed the left and at the same time strengthened the military power more forcefully.

Parallel to the political changes, during the 2000-2010 decade, Venezuela continued to position itself as the country with the most beautiful women in the world. An example of this was the famous back-to-back of Miss Universe in 2009, where a Venezuelan was crowned by her predecessor and compatriot. Four years later, something similar to that back-to-back occurred but with the presidency of Venezuela and as an excuse to continue the left’s legacy.

I grew up amidst these visual heritages and cultural, social, and political processes; that heritage, that interest comes from there. I am exploring these archetypes and relate them for their performative and symbolic coincidences. Investigating this topic allows me to dismantle a system of violence that operates on bodies in the service of the homeland, as well as on the binary visions of Latin America.

VI: This vision that you had of your country and its political-aesthetic history, did you also understand it more deeply when you emigrated to Colombia and managed to distance yourself from your country, or did it perhaps expand in some way through the migratory process?

AP: I think I always felt and thought about it, only in a more innocent way because I was a child. All of this becomes more complex when my identity and body are victims of corrective gender violence resulting from those binary archetypes. In a way, within Venezuelan families, everyone expects you to become a beautiful woman or a strong man. My family context and its ideological contradictions were very interesting. I grew up in a leftist family that was also fans of beauty pageants, nothing more capitalist than that.

Everything was very contradictory because sometimes they were broadcasting a presidential speech on television and after it ended, the Miss Venezuela pageant would start. Two forms of binary militarization in the media.

VI: (laughs)

AP: Those kinds of situations happened, very real ones! (laughs) But undoubtedly, emigrating changed how I assumed the identity of my country. The focus of the research I am currently working on is something that happens after migration and being a bit distant from my life in Venezuela.

When I emigrated to Colombia in 2019, I began to think about binary violence from my family archive, and from those inquiries came my project Dead Family, and also Dead Homeland, which is an expansion of the previous work. In the first, I revisit family memory, and in the second, national memory from the idea of militarization.

VI: Of course, and although this “mix” of the military and beauty pageants may be unexpected, I feel there is also an aspect of “militarization” when we think about the standards promoted in society. This is also linked to the fact that our contemporary existence is simultaneously governed by the hyper-visibility of images of violence and the saturation of entertainment content in the media.

AP: Absolutely. The body is constantly subjected to militarization directed by the dictatorship of gender (one of the longest dictatorships in history). In fact, I am interested in developing, in Dead Homeland, a visual language linked to entertainment culture and media. That’s why I use satirical and hyper-fragmented interventions or those slightly “pop” landscapes. Connecting this culture of mass media with the figure of the Military and the Miss is a mix that helps me highlight the inherently popular or pop nature of those stereotypes. Although the coincidences may not be so obvious, there are many common symbols that I weave into this project.

VI: Like what?

AP: For example, when the president is honored, they put a sash on him, just like the beauty queens. There are those nods that are ultimately symbols or social performances that turn these bodies into aspirational archetypes.

In Venezuela, and I dare say in Latin America, there are dynamics that force children to be part of these binary filters. School beauty pageants to choose the school queen are another example of that. I remember my elementary school classmates dreaming of being Miss Venezuela, and most of the boys wanted to join the military or become police officers. These pieces of evidence speak of a body indoctrination that is installed from childhood.

So, there’s something there that I also find very pop and aspirational because these archetypes represent figures of power in Venezuela.

VI: Of course. This about possibilities is largely linked to the possibilities of existence given to us as sexually dissident people, not only in society but also in the family nucleus during our childhoods. Could you talk about how the aesthetics of the work act as a form of identity validation?

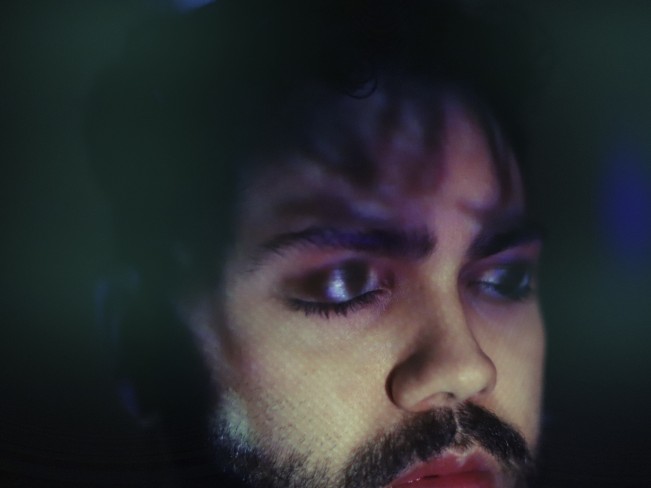

AP: All my projects have a saturated and expressive aesthetic to intervene in binary history and fill it with queer symbols. Memory, for me, is the main input in all my projects, but particularly dissident memories that are invisibilized from Official History. In Dead Family, for example, I work on resistance and queer representation within the hetero-family tradition.

But in Dead Homeland, that invisibility of queerness focuses on national memory. And it’s because national memory or archiving is linked to gender conflicts. The figure of the historian is usually masculine, but in family history or domestic archives, the figure is feminine. That is, those who are responsible for organizing family history are almost always women because it is a domestic activity. But history with a capital “H” is more directed by men. So there is a gender power relationship here, which also opened my eyes when approaching the archive.

VI: ¿How did your approach to the archive originate and what is the process of finding these images like?

AP: Dead Family, a project I’ve been working on since 2022 and is still ongoing, started as a very personal chapter intersected by migration. This migratory journey confronted me with personal memories, and I discovered that I wasn’t truly represented in my family history; I didn’t appear there. Rather, it was a performance of me, right? A performance of masculine obligations that I had to execute because of this body born male and expected to fit within the cis-heteronormative biopolitics of the State.

When I realized that I wasn’t represented in my childhood memories, I opened a dialogue with my friends from the LGBTIQ+ community (my chosen family), and we started to discover that none of us were there. Those memories don’t represent us in any way. And it’s very tough because that’s where the work begins of reexamining family history and reclaiming it. One of the ways to do that is through intervention. That’s why my work leans towards intervention, both aesthetically and politically. Intervening allows us to reclaim without erasing. That gesture of recovery without extermination allows us to highlight structural violence.

As for the process with my personal archive, there was very little preservation of memory in my family, although they were deeply interested in remembering and had small altars with photos from the past. Preserving memory is a privilege not all families have. For families with less access to memory technologies, there’s the possibility of remembering through oral tradition. When I migrated, I had very little access to my memory. My sister has been my archival guide in this, obtaining all these files and sending them to me. There are other sources, friends who travel and find photos that resonate with my searches, and then they send them to me.

That’s the formal part, but there’s also the internet. I really like working with public domain archives because they’re accessible to everyone. It’s like an apparent democratization of historical memory. That accessibility interests me. In fact, in this project, I work a lot with footage from national television broadcasts or certain newspaper clippings. I work a lot with what I call “residual archives”. I’m interested in that marginalized and pixelated archive because resolution is also a symptom of visual stratification violence. Pixelated images are synonymous with low status.

This is something that runs through all my work as an image creator.

VI: You touched on many interesting topics. I’m particularly struck by the collective work, indeed, realizing that this isn’t just about Andrés Pérez but is a shared experience, which also led you to expand this project beyond your own family archive, to work with other people who share the same experience. Could you talk a bit more about this collective work?

AP: First of all, as an artist or photographer, I’m interested in erasing the image of the author. That’s why all my projects are collective. That’s the first thing, right? And then, I believe we all have a responsibility to build memory. I know it sounds a bit dictatorial, but we have a responsibility, especially the queer community. We’ve been erased and continue to be erased as a strategy to maintain the conservative discourse of classic capitalist and heteroreproductive politics.

That’s why my work is collective. I’m always connecting with profiles that are just as dissident and marginalized as me. Trans women, trans men, non-binary people, bodily, sexual, sensory, and cognitive diversities. Anything considered abnormal and not preserving the well-being of a State that instrumentalizes us. I think individuality is an interesting aspect to rethink right now, especially with algorithmic policies. That feeling that we’re unique individuals is dangerous and weakens collective struggles.

VI: Absolutely. Speaking of intervention, in your projects, there are these visual nods to childhood, which are linked to memory. For example, the use of crayons and glitter on the photos, like something a child would write trying to reclaim this childhood. Where do you get this inspiration? Does play have a role in your work?

AP: Without a doubt. You touched on very, very important things. First, this “crafty” or “childish” language has to do with my interest in visual literacy. I’m interested in democratizing the reading of images and dismantling this hyper-intellectual discourse linked to the visual. I don’t just take photos for the photography circle or adults. I take photos for teenagers and children. I’m interested in them being able to see themselves in my images. So I think that crafty language connects me a lot with childhood. I always think, what will a diverse 12-year-old child think if they see my work? Will they be able to feel somewhat connected to that language?

VI: And play?

AP: Play is everywhere. I actually think all my artistic and visual processes start from play, from the exploration of a childlike Andrés who is recognizing the world and approaching certain topics. I allow childlike Andrés to flourish and reclaim a part of his childhood. Play as a method activates all the senses and emotions. When you play, you have to be fully engaged, and as a photographer, I don’t like to work only with the eyes.

VI: In this case, besides being a visual literacy strategy, it’s also a process of political awareness about our identity position in the world. This is something you also do as an educator. Could you talk a bit more about this visual identity pedagogy?

AP: Yes, absolutely. My pedagogical component focuses on gender and diversity. I always invite people to think about history from a diverse perspective, not only in relation to the LGBTIQ+ community but in relation to humanity, to all of us who exist. For the people who take my workshops or are interested in my education and support spaces, I’m interested in activating a political role with a gender and class perspective. Another thing that I find extremely important, not only in my teaching methodology but in all my work, is not just discussing diversity. It’s also confronting “normative” people because many of these normative people, or those who seemingly have no conflict — because, in reality, all bodies are in conflict, it’s just more evident in some bodies than others — discover that there is a conflict, that something is happening. This is something that is central to my work. I do a lot of research around the LGBTIQ+ community, but really, the body that I’m putting into discussion is the normative body because historically, queerness has been pathologized, and we are the bodies under study; we are the anomaly.

In this case, in my work, the body under study is the normative one. This activates critical thinking in everyone.

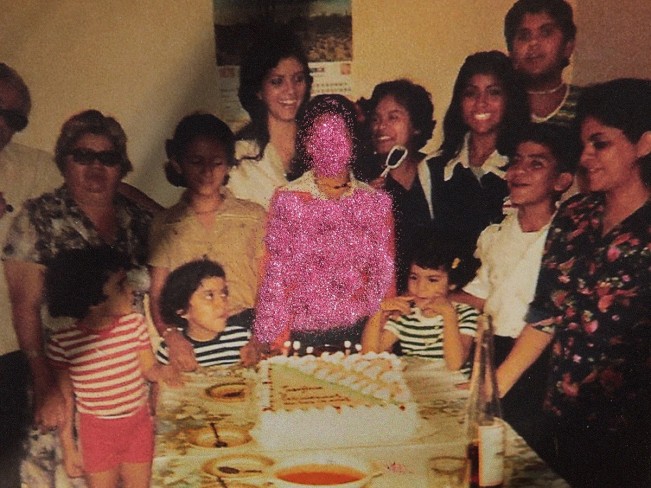

VI: Shall we talk about specific photos now? Let’s start with this one. Who is the person with glitter on their face?

AP: She’s an aunt named Josefina. In this photo, she was celebrating her 15th birthday. I grew up in a matriarchal family. All the women were in charge of the family, but in reality, they were subjected, despite the absence of masculinity. If you look closely, in the photo, there’s this man who is literally stepping out of the frame, and that’s how the original photo is. Despite the low presence of men, patriarchal structures were deeply ingrained within the family. It was very striking to see all these women in my family perpetuating machismo, for example.

On the other hand, in the photo, there are these two individuals who are also diverse figures in my family. There’s an uncle whose sexual orientation we’re not exactly sure about, but he was very diverse in the way he expressed his identity. And the other diverse figure is the first uncle to openly declare himself homosexual in the family. That was quite a process.

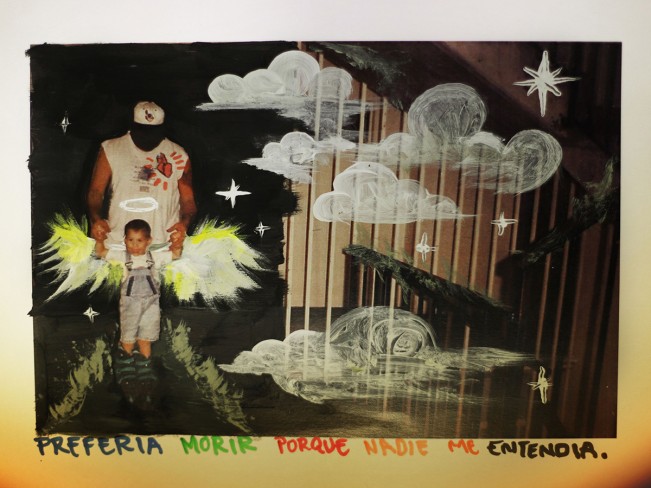

VI: What’s the story of the photos with the broken glass?

AP: Well, this is also very personal, like all my processes, actually. But this one particularly is very painful because in this image, we see cutouts of photos where I appear as a child, along with my sister and my cousin José, who from my generation was the first diverse identity to be revealed against the heteronormative family dictatorship. It was very difficult for José to live his diversity, so much so that he took his own life. In fact, that’s the reason why I started this project. In my family, they said that my cousin took his own life because he was homosexual. Diverse identities sometimes can’t survive within those normative family structures, so they prefer to simply make the decision to end their lives.

About eight months into working on my Dead Family project, I started working with a girl I’ll call M, who is 16 now. I remember she approached me and asked if I was going to Pride that year, which I think was 2022. It turns out one day she tells me she’s taking a makeup course and… she wanted to do drag makeup on someone and asked if I would accept, and I did.

In that process, she came to my house, did my makeup. That day she told me something very painful. She revealed to her mom that she was bisexual, and her mother’s immediate reaction was to try to intervene to correct her. Over time, amidst many personal processes, her mother threatened to send her to conversion therapy.

So that impacted me a lot because I had no idea that, even though it’s illegal, here in Colombia, for example, there are these spaces of conversion therapy. From that moment on, I took on a protective role with her.

I connect my cousin’s story a lot with hers. In fact, it was a moment where I said, “Stop thinking like a photographer, think like a human.” I had to become a protective figure for her so she wouldn’t be so alone, thinking that she wouldn’t experience the same fate as my cousin.

VI: Andrés, thank you very much for this interview. I’m interested in knowing what your plans for the future are. Where do you think these projects are headed?

AP: Well, to be honest, I never plan so much. Lately, I’ve been connecting with diverse identities from generations past to mine, so that these people also somehow take control of their memories. Familia Muerta is a project that works with very current dissident memories. So realizing that allowed me to expand the temporalities of my work. In fact, two days ago, I met with Karen, who is a 50-year-old trans woman from Colombia who had never had her photo taken on the street wearing a skirt, and I took a photo of her as an offering. So I think that’s where I’m headed, working with the intergenerational, not just my generation dialoguing with its past, but also starting to dialogue with those past generations that are important because thanks to their resistance, we are here today.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026