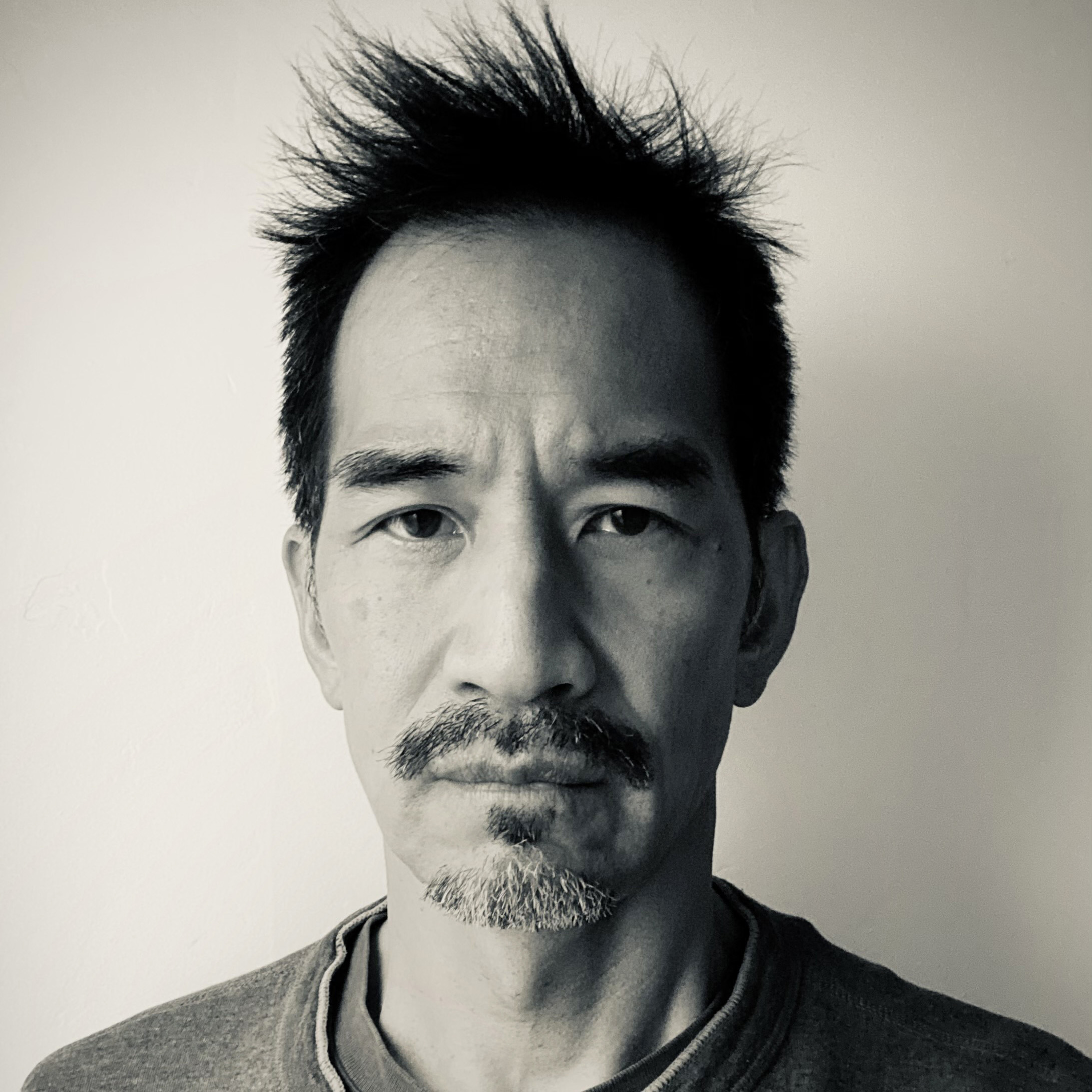

CENTER BLUE EARTH FISCAL SPONSORSHIP: MARK LEONG

© Mark Leong, A collective of graphic and performance artists mix traditional and modern creativity in this outsized version of bixian (ghost pen) where only one knows what word is to be written and physically struggles to make the others write it his way.

Congratulations to Mark Leong for being selected for Blue Earth Fiscal Sponsorship Award recognizing his project, Coming of Age: China’s Post-90s Generation . CENTER is pleased to add the Blue Earth Fiscal Sponsorship to their services for photographers and filmmakers. CENTER sponsors documentary projects that educate the public about critical environmental and social issues and is primarily interested in work that is educational in nature. They considered proposals of any geographic scope involving the photographic and motion picture mediums. As a non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status, CENTER is eligible to receive grants and tax-deductible contributions from private foundations, individuals, or other entities. This Fiscal Sponsorship does not include direct project funding or grants.

The Award includes a 1-Year Sponsorship, Professional Development Seminars, a Review Santa Fe Admission and Project Presentation, a Project Publication with Lenscratch and Inclusion in the CENTER Image Library & Archive.

The selection committee were Blue Earth Council Members, Staff & Board Members from CENTER & Blue Earth Alliance Teams.

Mark Leong is a fifth-generation Chinese American documentary photographer from Sunnyvale, California. After graduating from Harvard in 1988 with a degree in Visual and Environmental Studies, he received a Gardner Fellowship to photograph the following year in China. In 1992, he was in residency at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing, sponsored by the Lila Wallace Foundation. Beijing became his long-term base in 1997, from which he photographed throughout Asia. In 2003, he joined Redux Pictures. His book China Obscura was published in 2004. After more than two decades in China, he returned to the San Francisco Bay Area where he now lives.

He is a contributing photographer for National Geographic, and his stories have appeared in Time, Fortune, the New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker and Smithsonian. Honors include the National Endowment for the Arts, Fifty Crows, the Overseas Press Club, and the Open Society Foundation. In 2010, he was named the Wildlife Photojournalist of the Year for his coverage of the Asian wildlife trade. Shows include Carpenter Visual Arts Center, San Francisco Arts Commission, Leica Gallery Frankfurt, China National Museum, Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture Shenzhen and Photoville.

Follow Mark Leong on Instargram: @markleongphotography

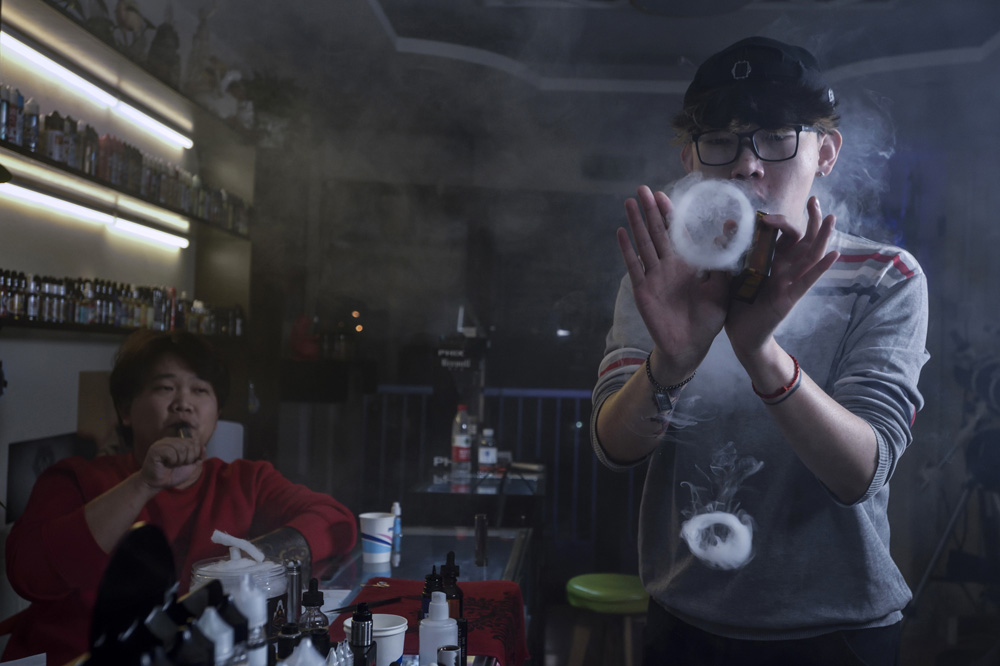

© Mark Leong, Shenzhen is known as China’s most youthful city, with young migrants coming from all over the country to try to make it in this industrial, hi tech city. The average age is under 30.

© Mark Leong, A pottery master, 28, worked in Suzhou at a factory making iPhone and iPad cases before returning close to home in Jingdezhen to do traditional ceramics. 95% of the people he grew up with became migrants but few have returned from the cities.

Coming of Age: China’s Post-90s Generation

In 1980, fearing the effects of overpopulation in what was already the world’s largest country, China implemented law limiting couples to a single child. This was arguably history’s biggest social experiment. What happens in a society built on four thousand years of traditional clan connections, where brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins abruptly go missing? The full effects of these gaps are still unclear and will continue to emerge for decades.

In 2018, I started a long-term project photographing “post-90s” young urban Chinese adults under 30 — just after the government ended the one-child policy. Called “little emperors” for their heliocentric importance in their families, this cohort of single children were born after 1990, just as China was lifting itself out of centuries of turmoil and poverty to become a superpower. Lacking siblings but fortified with money, technology and political stability, it was as if they had grown up on a different planet than their parents.

Now come of age, these two hundred million young adults are poised to impact the world. But they also an untidy array of increasingly fluid personalities dealing with previously unknown choices and pressures in a much more globalized China with a greatly diminished social safety net. Over two years, I sought out and photographed many varied experiences — hi-tech migrants, hockey players, grad students, gig workers, transgender activists, organic farmers and online influencers. Then came Covid-19 and I had to leave without completing my project. The attached photo samples are from this 2018-2019 work.

China has now reopened. Support from CENTER and others would help me return and update my subjects’ stories as a next step in what is shaping up as a longitudinal project. Five years is a significant amount of time in any young person’s life. Over this period, I have kept in touch with many of my subjects via WeChat and other social media. Some have graduated, started/ended relationships, switched jobs, progressed gender reassignment or gone overseas. Some are over 30 now and have their own children. But these expected changes have been additionally stress tested by the pandemic, which in turn has exacerbated economic stagnancy and ideological repression.

My hope is to make two more trips to China, primarily working in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. New photographs will update my subject’s lives, following their individual paths but also looking for current tensions: overwork versus unemployment; family/societal expectations against personal choices; patriotism against the desire to leave China; and creative expression under political surveillance. Their words and stories will detail their experiences, attitudes and emotions through Covid and beyond. In a time when popular internet memes about just giving up — “lying flat” and “letting it rot” — show the dramatic drop in youth confidence since I was last in China, this project will also look at new sources of resilience: spiritual practice, reverse migration to rural hometowns, wellness support and underground artistic collectives.

Since 1989, photographing Chinese young people has been a constant thread in my career, covering rock bands, internet hackers, entrepreneurs, factory workers and self-labeled “hooligans.” While I am ethnically Chinese, I am still an outsider who came with a preconceived notion of Chinese people as a monolithic bloc of conformity. One of my goals, then, has been to share the realities of diverse, nuanced lives in this most massive of mass societies — especially crucial in this divisive time of geo-political unease.

In addition to visually documenting this generation’s stories for public exhibition and national media publication, I am interested in using my process with this project as teaching material to parallel what my students are doing. Since last year I have been leading photo workshops at the UC Irvine Humanities Center about identity, community maintenance and repair; we are hoping to expand this to include an travel exchange program between college students in China and the United States. – Mark Leong

© Mark Leong, University students dress up in traditional Chinese hanfu costume. To promote China culture above imported Japanese cosplay or K-pop, the hanfu club is the only student-run organization to receive funding from the university.

© Mark Leong, An agriculturist trims organic tomato plants at a communal farm. She came from a farming family and went to technical college to study horticulture. She found that 80% of the graduates in their field went in to the pesticide industry, but, sickened by the smell of the chemicals, chose to pursue organic farming instead.

© Mark Leong, The activist on the left was born a boy, and is now in the process of becoming a woman; she works on a trans support hotline. The activist on the right was born a girl, and is now in the process of becoming a woman; he travels and gives public talks about transgender issues.

© Mark Leong, Graduating college seniors spend 18 hours a day in their final semester cramming for graduate school entrance exams. There is even more pressure than the famous “gaokao” tests to go to university, as there are far fewer available spots.

© Mark Leong, Young couple in their Shanghai apartment. They met in university, where they were classmates in the digital media department. This relationship ended when she left for London to study for her MFA.

© Mark Leong, Anybody can be a star in this traditionally self-effacing society. At 18, this wanghong (internet star), posts livestreams and TikTok videos of himself singing, chatting, and putting on makeup. He claims 120,000 fans, including many older men who send him “gifts.” Re: media criticism of “sissy boys” he says: “They judge masculinity by appearances rather than character and responsibility.”

© Mark Leong, At a music festival, fans who have met each other via WeChat and Weibo online gather together to see their favorite hard rock band, Reflector.

© Mark Leong, To escape urban pressure, friends who used to skateboard and listen to reggae in northeastern industrial Shenyang spend much of the year on the Inner Mongolia grasslands.

© Mark Leong, Industrial designer, 24, was the first person in her Hunan village to go to college. These days, other migrants like her with bachelors and masters degrees flock to Shenzhen, where she works at a furniture company. The photo shows her moving her boyfriend’s stuff as he changes apartments in the “urban village” where they live. They got married in 2022.

© Mark Leong, Love In the Time of Facial Recognition Software. Young couple spends part of the weekend visiting Tiananmen Square. Like all visitors, their every move is recorded from multiple angles by the surveillance cameras that festoon many of the lampposts.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026