Aurora Rojas Briceño: Amalia Irma

This week is dedicated to Chilean photographers working across a variety of media. Today’s feature is dedicated to Aurora Rojas Briceño and her photobook project Amalia Irma, which documents the everyday life of her grandmother.

Aurora Rojas Briceño. Professional photographer, graduated from the Foto Arte School of Chile and a member of the Photographers Cooperative. From 2015 to date, she has participated in various workshops taught by renowned photographers at festivals, such as Lourdes Grobet, Marcos Lopez, Cristina de Middel, Gisela Volá, Yumi Goto, Musuk Nolte. In 2018, she participated in the Wabi Sabi Residency in Delta-Tigre (Buenos Aires, Argentina) under the curatorship of Romina Resuche. She has been a resident artist in two projects of the Red Cultura Program (MINCAP) in the Atacama and O’Higgins regions. She has conducted photography workshops for the Subdirectorate of Culture of the Municipality of Santiago, and at the Aiep Professional Institute. In 2022, she published her first photobook titled “Amalia Irma” (Fondart Nacional), presented at the StgoFoto Fair. Her work has been published in different virtual platforms and national and international print publications, such as WOPHA Foundation, Letargo Revista, Revista BEX Latinoamérica, and Femgrafía.

Follow Aurora on Instagram: @austral.aurora

Vicente Isaías: Your project delves into the everyday life of your grandmother, Amalia Irma, and her relationship with the house where she lived her whole life. What led you to approach this project from such an intimate level?

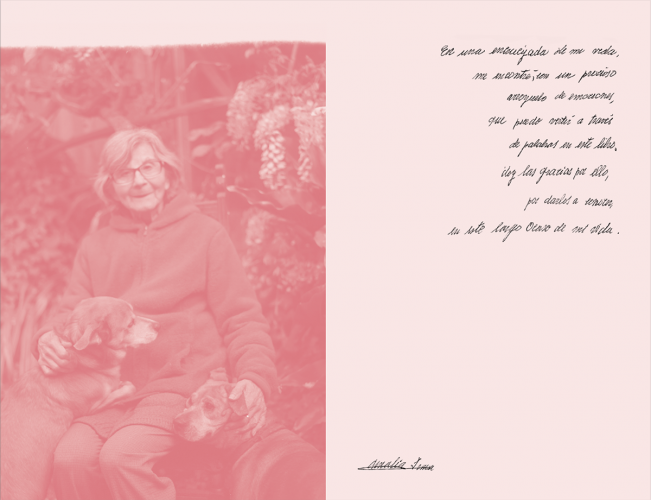

Aurora Rojas Briceño: Honestly, I wasn’t aware of the level of intimacy that this project entailed until we were working on the book editing with Andrea. In this sense, her perspective was crucial. In fact, it was one of the first topics we discussed when we started editing the photobook. So, we decided to involve Amalia in the process, and she herself reviewed and approved all the mock-ups we edited before reaching the final work.

Personally, it was a slow process that took me about a year to distill. And it ultimately resulted in the text I wrote for the photobook. There, I found myself compelled to articulate in words what I couldn’t convey through images. I acknowledge that it was quite a challenge to find the right order and words to explain the nature and the very intimate feeling of this work without feeling entirely exposed.

I suppose that the history and our particular relationship with Amalia led the project down this path. And if I think about it, I can’t imagine it any other way.

VI: Can you tell us more about your relationship with your grandmother? What is one of the memories you cherish the most of her?

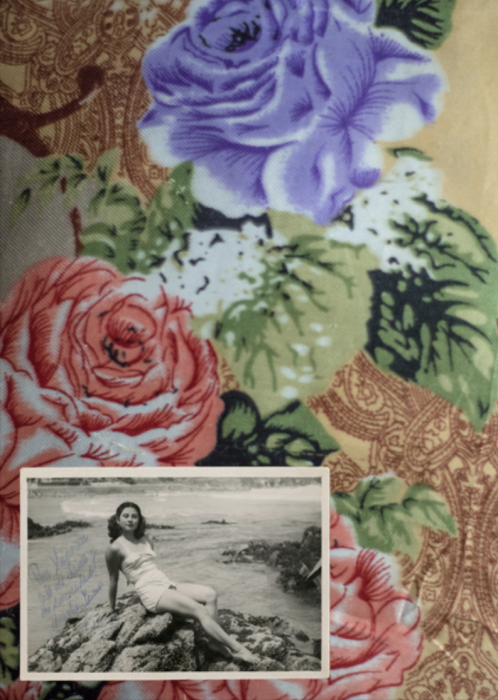

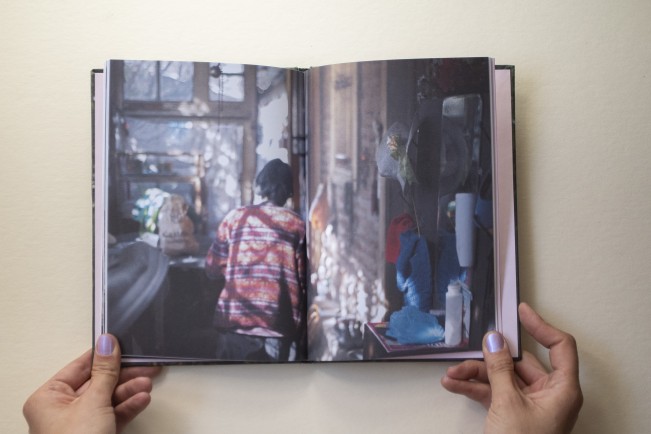

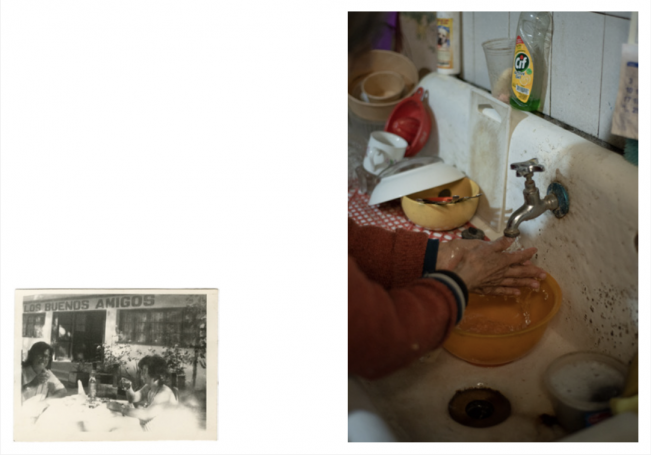

ARB: Our relationship began in her house, which is the same place where I grew up. My grandmother was a rather silent and elusive woman. She wasn’t the typical grandmother from stories who knits sweaters and bakes cakes for her grandchildren. And although we lived in the same shared space, we didn’t relate to each other deeply. Until, by the twists of fate, I mentioned to her the idea of doing a photographic project where her house would be the protagonist. From there, we started to connect and get to know each other more deeply. I began to delve into her family photo archive, and little by little, I understood her and discovered all the things we had in common: her love for animals, nature, trees, poetry, or even physical resemblances, like our hands or her little nose. And during that process, my project about the house took an unexpected turn and also turned towards her.

In August 2022, we were able to publish the photobook Amalia Irma, and we presented it at the STGOFOTO Photobook Fair. Amalia, my maternal grandmother, was able to attend the presentation that day (by then she had already experienced some health setbacks) and she was the special guest. I remember that, at the end of the photobook presentation, there was a loud applause from the whole family, friends, and people who attended the fair presentation. And there, in the front row, sat Amalita, with her bright, slanted eyes. That moment is my greatest treasure.

VI: What is the process like for capturing these photos? Is it a collaborative process, to what extent is there direction, or do you prefer to create more candid nature images?

ARB: Throughout my process and the experiences and learnings I’ve gained as a photographer, my approach to the moment of shooting has obviously changed. But personally, I believe this has had much more to do with my confidence than any other factor. Likewise, while working on editing the Amalia Irma project, I could see, upon reviewing the archive, part of this change.

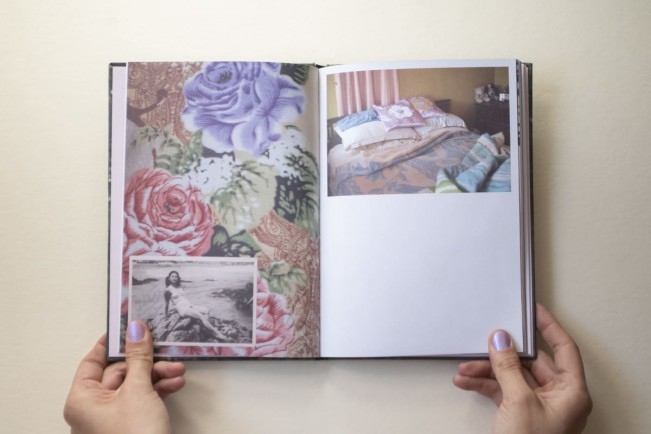

Regarding how I handle the relationship with the person being portrayed, I’ve learned that before picking up the camera, I need to converse, learn a bit more about their story, something that allows me to connect with them. For this reason, I believe my process is more collaborative, and as much as the person allows me, I enter their intimate space. With Amalia, it happened that, in a way, I tried to intentionally capture some photographs, especially some close-up details and the last portraits I took of her. But generally, I try to interfere as little as possible, both in direction and lighting, where I prefer to use natural light and do without flash or other accessories. Sometimes, if necessary, I “play” with the ISO to generate a certain grain in the image, which sometimes confuses people about the format of the photograph, and they can’t tell if it’s analog or digital. I like to experiment and play with that because there’s something about the hyper-definition of digital that I don’t entirely like.

VI: Is there any pattern or motif that repeats in the project, intentionally or arbitrarily?

ARB: The house and its corners, from the beginning of the project, were the main motivations. And by the time we started editing work with Andrea, we agreed and decided that these would be the fundamental elements in the narrative, both of the photobook and the exhibition of the project. Because, in each of these spaces and little corners of this green refuge, there was Amalia: in the red plastic roses she placed in the flowerpots, in the papers where she wrote down the schedules of her medications, in her thoughts in moments of solitude, or in the photos of unknown animals that she cut out and pasted around her house.

VI: To what extent does this work reflect social realities that go beyond the family biography and instead encompass the reality of the elderly in Chilean society?

ARB: While the project, from the intimacy and everyday life of Amalia, reflects certain issues that affect her politically and socially, simply because she’s a woman and elderly in Chile, a country where aging comes with meager pensions, where the concept of “the loneliness epidemic” has been accentuated, and where the suicide rate among the elderly is a reality that cannot be denied, it was never my intention to create a project with a political impact. However, as a photographer and artist, I believe that these types of works should always be approached from a standpoint. In my case, as a woman and a feminist, I not only created images that portray the relationship I established with my grandmother and what it has meant, transgenerationally, to be a woman in my family, but I also ended up making a documentary portrait of what it’s like to age, for a woman from a lower-middle-class background, in Chile. And in a way, it’s the intimacy and everydayness of the project that makes it political because it connects with the reality of many people, especially women, in our country. You see how granddaughters connect with their grandmothers, daughters with their mothers, and elderly women, like Amalia herself, manage to connect with their pasts and their personal stories, adding deep value to the meaning of my work. So, the project ends up being a universal portrait of what it means to age. And that, not only in our country, is a very deep social problem that, despite being addressed in different works, remains unresolved. In my case, my images tried to bring dignity to my grandmother’s aging process. And I believe that’s the most political aspect of my project. Because in our country, most women do not age with dignity.

VI: Recently, you had the opportunity to exhibit this work in the exhibition Amalia Irma, the green home where your heart remains at Estación Mapocho. Can you tell us about the process of setting up an exhibition and what have been the biggest challenges?

ARB: Amalia Irma, the green home where your heart remains, is my first solo exhibition. This project is about my maternal grandmother, Amalia Irma, her house, and the process of how we got to know each other. So, this whole experience was new and a tremendous learning curve for me, both in curating the exhibition with Andrea Aguad (the exhibition curator) and in its production.

The year we received funding for the exhibition, my grandmother suddenly passed away. And her departure delayed the start of the project. By the time we resumed it, I had landed a job in another region. Taking on this new job, with greater responsibilities and extremely long work hours, coupled with the distance and lack of time, were the biggest challenges in this entire production and exhibition setup process.

Before the exhibition, I had published the photobook “Amalia Irma,” where I also worked with Andrea Aguad as the editor of the publication. So, despite being a very different process, the trust and her connection to the project synergized and helped us to align when crafting the narrative. And we were able to carry out all the editing and museography work for the exhibition through virtual meetings.

We spent a week setting up the exhibition itself. First, we installed the stickers which, after several attempts, we managed to fix to the walls. For the assembly of the works, Daniel Jara, the installer at Estación Mapocho, collaborated with us, facilitating and expediting the work to meet the exhibition deadline. Despite encountering several technical challenges during the process, we always managed to find a solution. But to summarize, the distance and lack of time were the most difficult aspects to overcome.

VI: Tell us about the book publication. What has been the process of navigating the publication of this project like?

ARB: In my experience, publishing this book was a bit of a crazy journey. And based on other experiences I’ve heard, most people seem to agree with this. I suppose that’s the beauty of it. And while many things happened during the editing and publication process of this project, today I feel and believe that, in some way, they all contributed to making the book what it is now, especially the stumbles and difficulties that had to be overcome. I am grateful for the process because in nearly two years since publishing the photobook, I’ve had the fortune to present and share the project in different places and regions of the country, both in national festivals and cultural and educational spaces. And being able to participate in each of these encounters, where I’ve been received with affection and there has always been synergy or a word of support and admiration for my work, has undoubtedly been the best reward for me.

VI: I’m very interested in creators who live away from major creative centers. I feel it’s necessary to open conversations about opportunity and territory. You currently live in Ovalle, far from the bustling urban center of Santiago. How has this affected you in terms of opportunities or visibility of your work?

ARB: I think it’s important to say that I’ve only been living outside of Santiago for almost a year now. And during this time, my biggest obstacle has been the time and distance to be present in the activities where I’ve participated with my project.

Anyway, in terms of opportunities, it hasn’t always seemed easy to access them, even while residing in Santiago. And although my comment may seem unpopular, I believe there’s a false idea that there are more resources for artists in the capital. And in our particular field, I think the issue of competitiveness and state funding, where only 10 to 15% of applicants have access to resources, has deepened the precarious situation of photography in Chile. And I believe, and it’s relevant to mention, that the closure of the photography department of the Ministry of Culture, Arts, and Heritage underscores the current neglect of our guild.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026