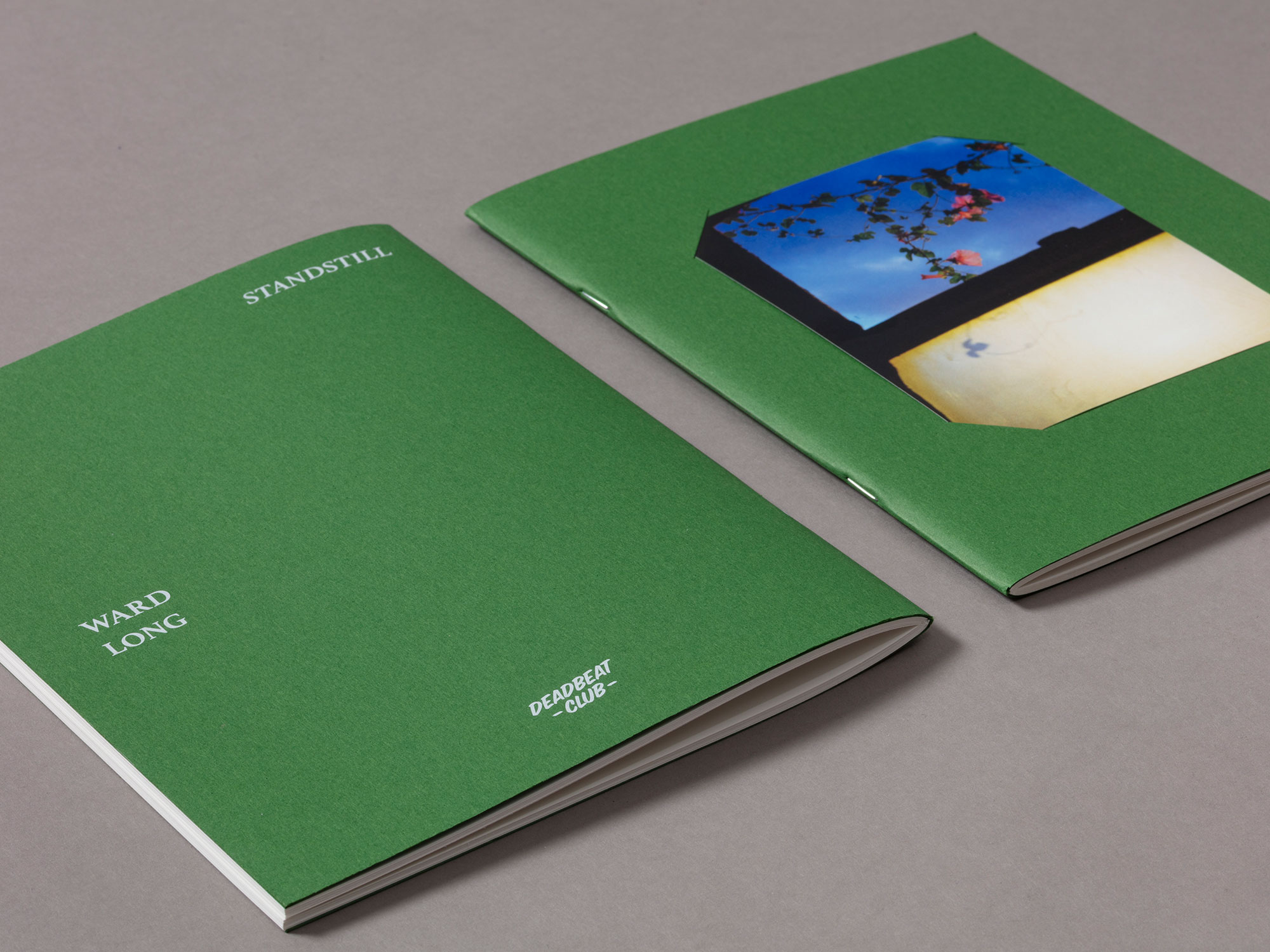

Ward Long: Standstill

How do we acknowledge a time of transition? Or perhaps a more pertinent question is, how do we cope with the loss of what was and the uncertainty of what is to come? For Ward Long, the answer is to photograph your way through. Standstill, his latest publication from Deadbeat Club, is a collection of quiet moments, pictures made in-and-around his home in Oakland, California before he moved south to start a new life in Los Angeles. A follow-up to his previous book, Summer Sublet, this new iteration presents a familiar setting, previously teeming with life, that has now come to rest, the golden glow of California illuminating the tiniest of details of this life pause. Assembled into a thoughtful sequence, Standstill invites us into Long’s meditation, an unhurried place that I am more than happy to visit and stay for a while. I caught up with Ward to delve deeper into the ever-changing thing we call life and the process of photographing through it all.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Tracy L Chandler and Ward Long.

Ward Long is a photographer living in Pasadena, CA.

Follow Ward Long on Instagram: @wardlong

Standstill is a 48-page soft cover booklet available for purchase from Deadbeat Club. The book is also available as a special edition packaged with a signed print.

Deadbeat Club is an independent publishing group & coffee roaster located in Los Angeles, California. Rooted in contemporary photography, their ethos on small run, limited edition publications carries into their small batch signature blend coffees.

Follow Deadbeat Club on Instagram: @deadbeatclub

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram: @tracylchandler

TLC: Standstill is a follow up to your first book with Deadbeat Club, Summer Sublet, a slow observation of living in a house full of women. In the text of Standstill you write, “The time came. My roommates moved out and started having kids. I stayed.” It sounds very existential. I imagine you in this big house all alone asking yourself, “What comes next?” What came next for you? Did you photograph that too?

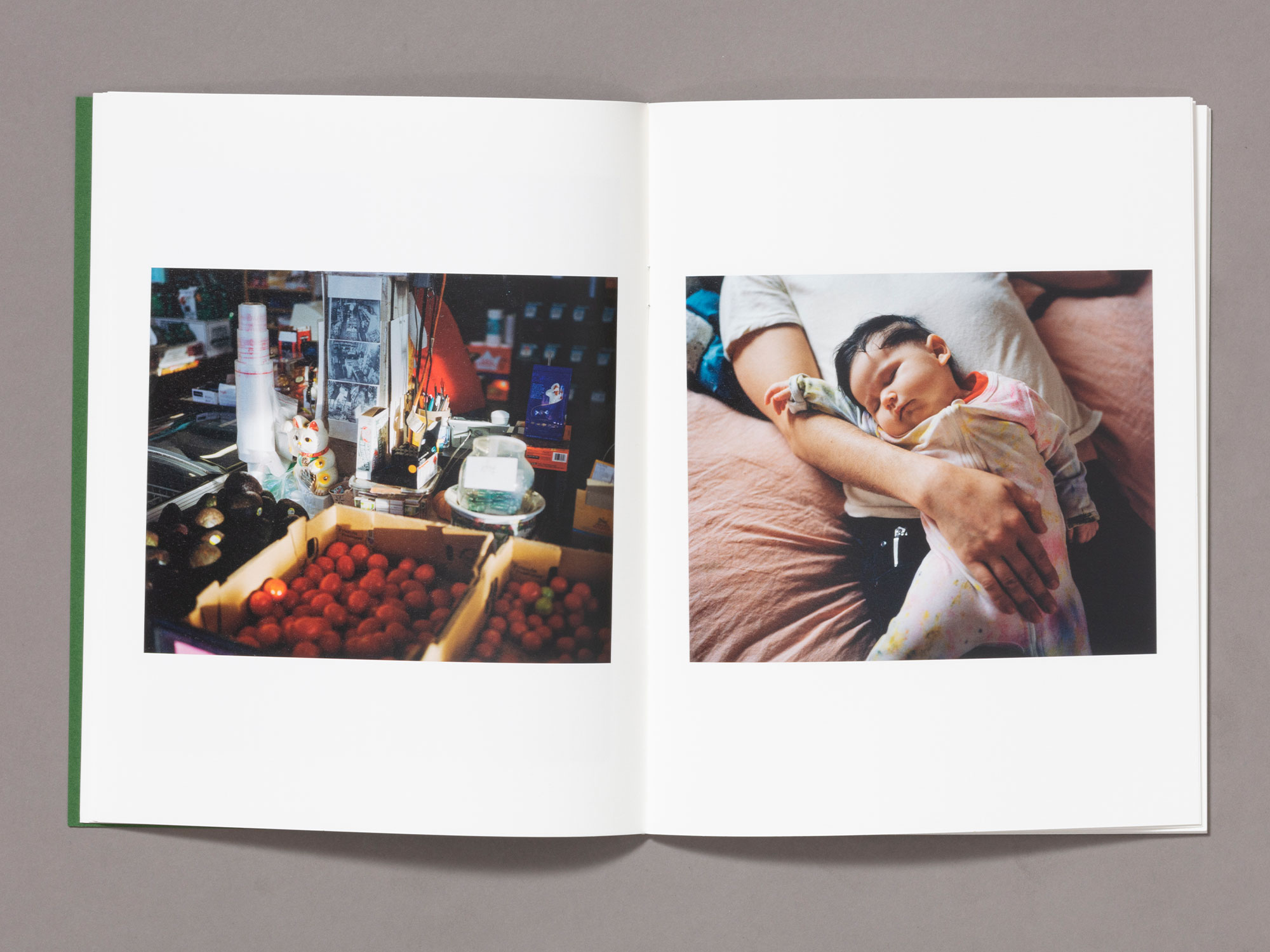

WL: It was existential! At some points there were nine people living in the house, all making noise, running up and down the stairs, and trying to cook on the same four-burner stove. Then there were just three of us left. It felt like everyone else was growing up and changing.

Before Oakland, I always moved to another city as soon as my friends started stroller-shopping. I had a steady job and community here, but my partner Annie was finishing her dissertation. She wanted to teach, and I wanted to keep taking pictures. We might have to move wherever the tenure-track winds blew us. So I was feeling stuck in this in-between state, getting older but no wiser. Then the pandemic hit, and every future seemed more uncertain.

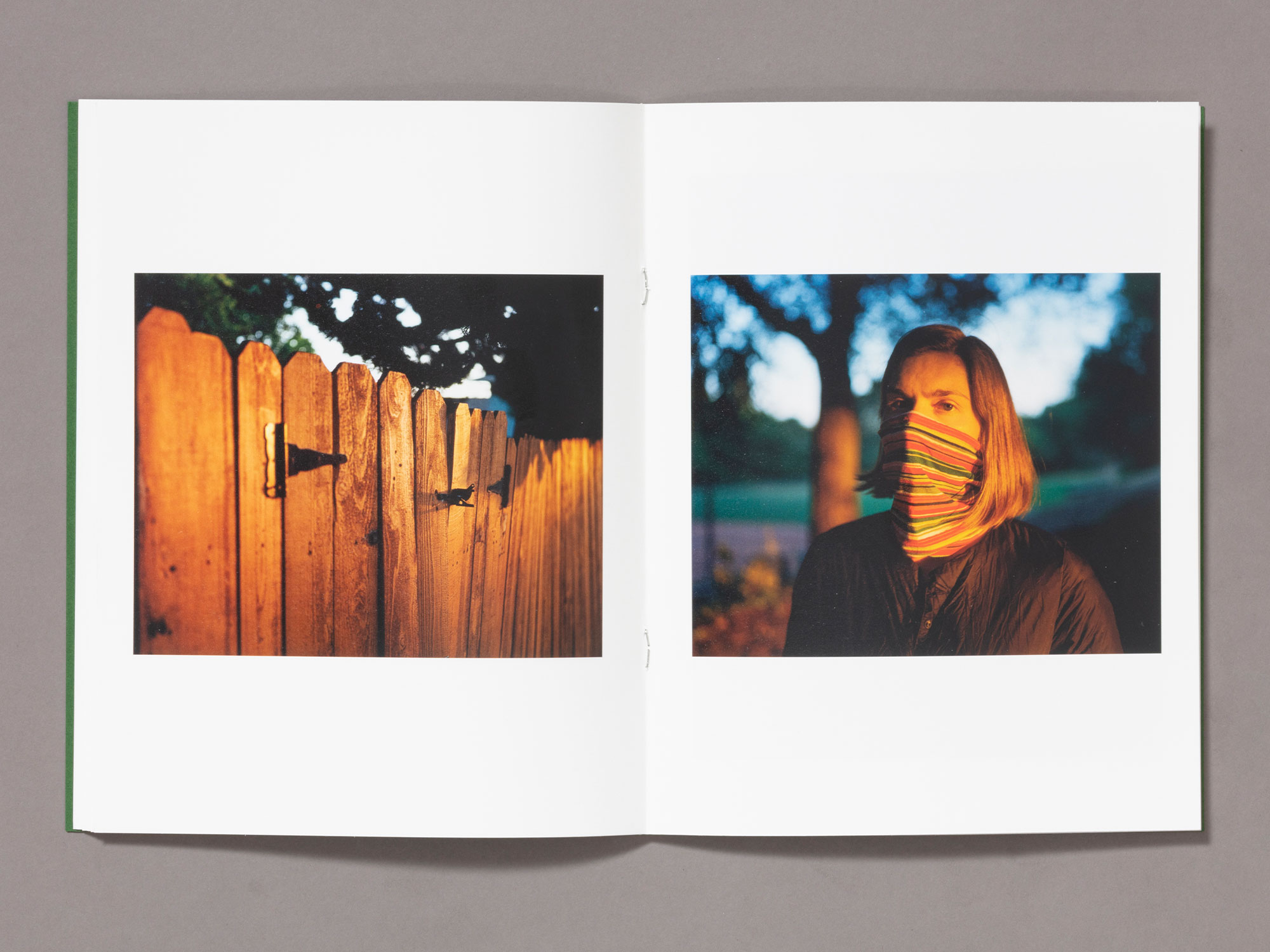

After making so many interior domestic portraits for Summer Sublet, I needed to get out of the house. I started making pictures in the neighborhood graveyard, a place where time and stillness collected. It quickly got crowded with joggers and picnics, so they closed it. I kept walking in parks and gardens, and I made a few pilgrimages to Dorothea Lange’s house on Euclid Ave. I tried to stay with all the uncertainties as I carried my camera. I shot color film and let the rolls pile up, hoping some unconscious meaning might come out later.

TLC: The opening sequence tells the story. The ivy in the opening image seems to gaze forlornly out the window and then the next few images take us outside into the world, then back in again, and so it goes. We see how you see, appreciating the quieter moments, the synchronicities. How long did you wait before revisiting those piled-up rolls? Were there any surprises? Did that unconscious meaning reveal itself to you?

WL: I shot for more than a year before taking stock. I scanned the binder full of negatives all at once in a month-long marathon. A few stood out right away. There was a burned out fast-food restaurant that said “McFuck You” on the side, a skeleton horse wearing a blue surgical mask and a red cape, and three men whitewashing woke graffiti off of a giant cross. These pictures were topical and loud, but they didn’t have that much to say. I knew what they meant at first glance, and that didn’t feel like enough.

Since I couldn’t make sense of the whole body of work, I moved through the pictures one-by-one. I color corrected and toned every frame like it was someone else’s prizewinner, ready for a big frame.

Giving every frame that kind of attention let me listen for the quiet ones, to hear what I only had the courage to mumble to myself. Once I had gotten through most of them, I tried to edit the work to be about something great and clever and external, like the seasons or the country. But if I was being honest with myself, they were about grief and fear, heavy feelings that would still fit in the palm of your hand.

I was afraid of moving on in life. I worried about everything I hadn’t yet done, and I couldn’t let go of painful doubts about the future. It was easier to watch life than to live it. Taking pictures was a way to stop time, to hold the world right here with me, a place where we could be safe and nothing had to change. But of course that’s an illusion, even in a photograph.

TLC: This really is a transition story, a suspension (dare I say a “liminal”) state between stages of life, clarity, and action. It is hard to not see the yearning in some of these photos..for what was. The mood is strong. It’s amazing what light can do. The same content at any other time would be a different story. I imagine you walking these familiar routes, seeing the same old objects perched around your home, how do you know when the time is right to make the picture?

WL: Clouds and fog love the Bay Area. It probably has something to do with the layout of the mountains and the ocean. It’s why everyone always carries a sweater, just in case. But then the clouds part or the sun sets and these gorgeous rays beam through the air and everything feels alive and specific. It comes in through the kitchen window and suddenly you can see all the little veins in a flower petal. In this group of photos, I was thinking about light as an everyday revelation.

Studio lighting is all about figuring out which strobes and reflectors are going to reveal a particular set of surfaces. Here it’s the opposite: given the sun and the clouds and the air right here right now, what can I see? Or to put it more spiritually, what is being shown to me? Pema Chodron has a saying that “This moment is the perfect teacher.” I think I was after something similar.

So when is the right time to make a picture? Probably when I’ve walked a mile or so and burned off a little anxiety. I’ve taken my earbuds out, taken a few other photos to warm up, and I’m not thinking too hard. It’s when I’m listening.

TLC: That golden state glow! It does choose its timing and I love that you are listening for it. Many of the objects caught in those sun rays, the rocking horse, the roller skates, the sidewalk chalk… they all nod to youth, innocence, and play. Were these themes you were consciously exploring?

WL: Early in the pandemic, my closest friends started having children. At that point I was still staying close to home and avoiding crowds, but there were little babies in my immediate orbit. I cared about these children so much, and they were so vulnerable. I would walk by playgrounds choked with caution tape, and imagine all of the kids that weren’t there. I was also wondering and worrying if I would have children myself, and if so, when?

So there’s a direct connection there, but I think so of the images of play are about finding ways to feel free. I was waiting for my life to change, and the news was always so heavy, and so there’s images of blood red suns, bridges to and from nowhere, cardboard gravestones, and explosions over empty parking lots. I think the images of play represent the opposite, a longing for lightness.

TLC: At the end of the book there is a short passage. One line speaks to that limbo state, “One day the sun didn’t rise. It sank in the wildfire smoke and stayed there. I drove into the city and sat behind a desk anyway. I didn’t know what else to do with myself.” Ugh, I can feel the longing for clarity and action. But I would argue that you did know what to do with yourself and you did act. You showed up for whatever was there at that moment and you photographed it. The passage ends with, “How do you move forward in life? Did my aunt still have my grandmother’s ring? There were many lives across the mirror. One of them was mine.” Where did you go from here?

WL: Well, I eventually did find my grandmother’s wedding ring. It was in a file folder labeled “Rings” in a box in my mom’s basement. I proposed, Annie said yes, she got that teaching job, and we left Oakland. We got married, and started a new life. It was beautiful.

Everything seems very clear looking back, but the rearview mirror doesn’t reflect all the painful doubt and uncertainty. It’s easy to forget. As my friend Bianca says, “Hindsight is 50/50.” But you’re right, I really did take a leap.

I saw the new Hayao Miyazaki movie. I take the meaning of his films to be an imperative: You must live. Whether it comes from his conflicted characters or the meandering plots I’m not sure, but those films make it seem heroic and vital just to continue on. I guess that’s why he can’t retire. But yeah … you must live!

TLC: This is your second collaboration with Deadbeat Club. I am curious if there was a shorthand from working together in the past or is every book a brand new start?

WL: Since Summer Sublet, I’ve worked with Deadbeat Club on a number of projects, mostly helping other photographers get their files ready for publication. But more than that excellent working relationship, Clint and Alex are some of my closest friends. I had made more than ten book dummies before they saw Summer Sublet, but this time they started helping me when it was still a pile of prints. I felt so exposed putting this work out there, and they really helped me shape the edit, the sequence, and how I talked about the pictures.

TLC: I love that. They really are the best. For your signed copies, I have seen that you accompany your signature with small drawings in golden pen.. Are they personalized for each person?

WL: I keep a notebook, and I try to write and draw a little bit everyday. I love the immediacy and the intimacy of it. A sketch or a scrawl can be so tender—hasty lines let you know that this was urgently seen and directly felt.

I wanted to cultivate that same kind of personal connection with Standstill. Adding a drawing or a few lines to each one is my way of saying “This one was just for you.” I want it to be like drawing a tarot card, suggesting that there’s some intuitive reason why a drawing of leaves showed up on your copy.

TLC: Yes! Or like reading tea leaves. You will have to sign/draw my copy next time I see you. I can’t wait.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

Curran Hatleberg: Blood GreenMarch 9th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026