Lisa Beard: Because It’s There

This week, we will be exploring projects inspired by memory, place, and/or intimacy. Today, we’ll be looking at Lisa Beard’s series Because It’s There.

I was astonished when I first came across Lisa Beard’s work this summer. Lisa submitted work to a summer open call hosted by Midwest Nice Art, a collective I run with my husband, Tim Rickett, and we were happy to feature her work in our annual juried exhibition, nice;02. Once I saw one work, I immediately viewed her website to see what I had been missing out on. Lisa shows the essence of appropriation in Because It’s There by transforming found photographs into completely new images. The relation to memory and the way we always alter our memories each time we think about them is essential to understanding the way we function within our experiences. Lisa is incredible at creating new stories through her transformation of images.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Lisa Beard: It came about as a sort of natural continuation of my MFA work, which I finished in the Fall of 2022, and my projects build off of one another, so this work is a result of what came before it and expands upon it.

To offer some context, I have always been interested in the human experience, but especially how the constant collection of individual experience collides with and relates things on the outside, the external. Shortly into my studies for my MFA studio work, while I started to dig away at my interests in memory, time, and perception, I came upon and became more interested in artists such as Proust, Duchamp, Johns, Cezanne, Rousseau, and Paz. Before I knew it, I also developed a strong interest in Gertrude Stein, who experimented with and used language via her creation of poetry, plays, and novels to explore what she called continuous present and insistence, and these became important ideas in my own thinking and work, too. Continuous present asserts that experience is always taking place and it always will, both inside of us individually and outside of us. So, to me, this means that literally, the only time that can be is now, right now, and thinking about what happens when memory is taken into account along with the idea of continuous present is pretty complex and fascinating. Insistence is related to the essence of a thing, a vital quality that has staying power through space and time. These two ideas caused me to become very curious about and to begin questioning the nature of reality and of truth, and also made me realize that these things parallel and relate to the medium of photography. Around this time, I was also aware that I was thinking a lot about what I make in relation to impermanence and wondering what the point of anything was, especially if reality and truth are in question. This framing of my work seemed bleak, pessimistic and not quite right for me and my worldview. Insistence seemed more fitting. I was more interested in what stuck around, especially across time. Plus, it seemed much more hopeful.

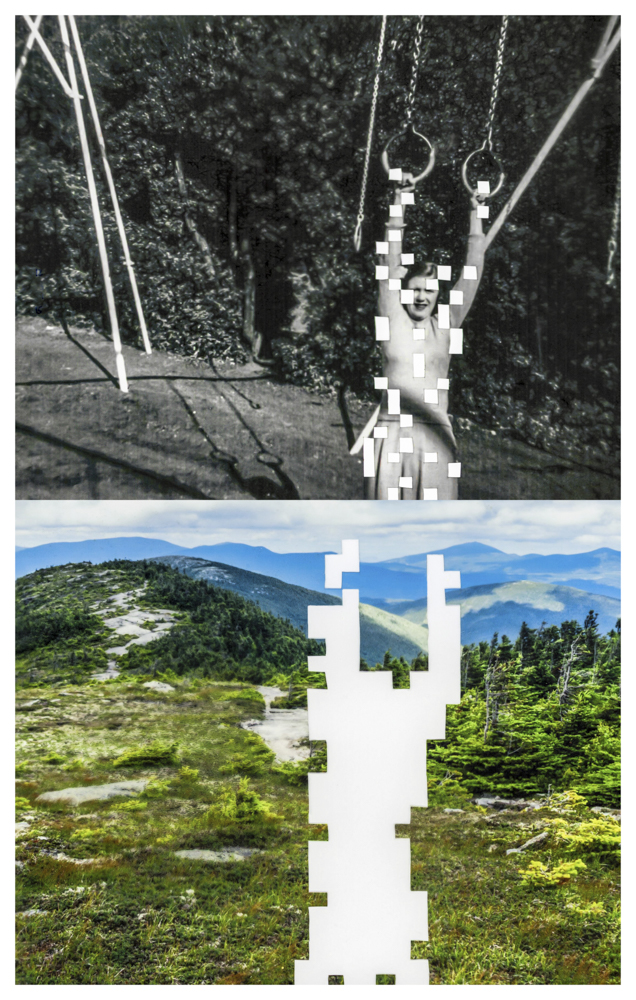

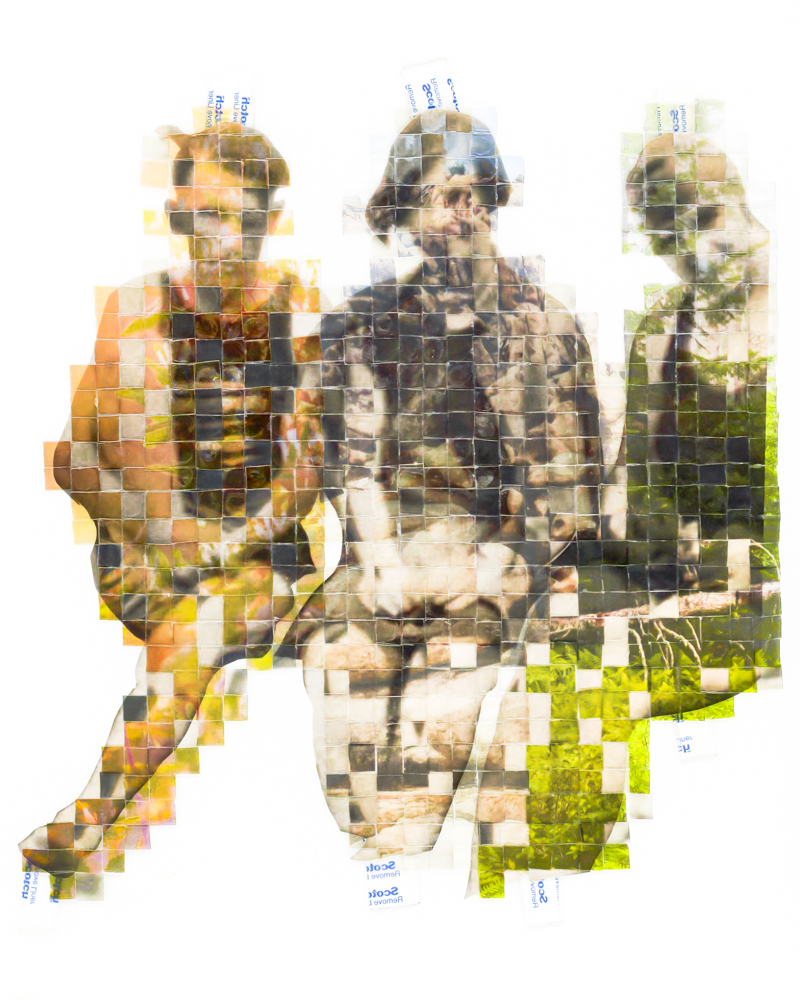

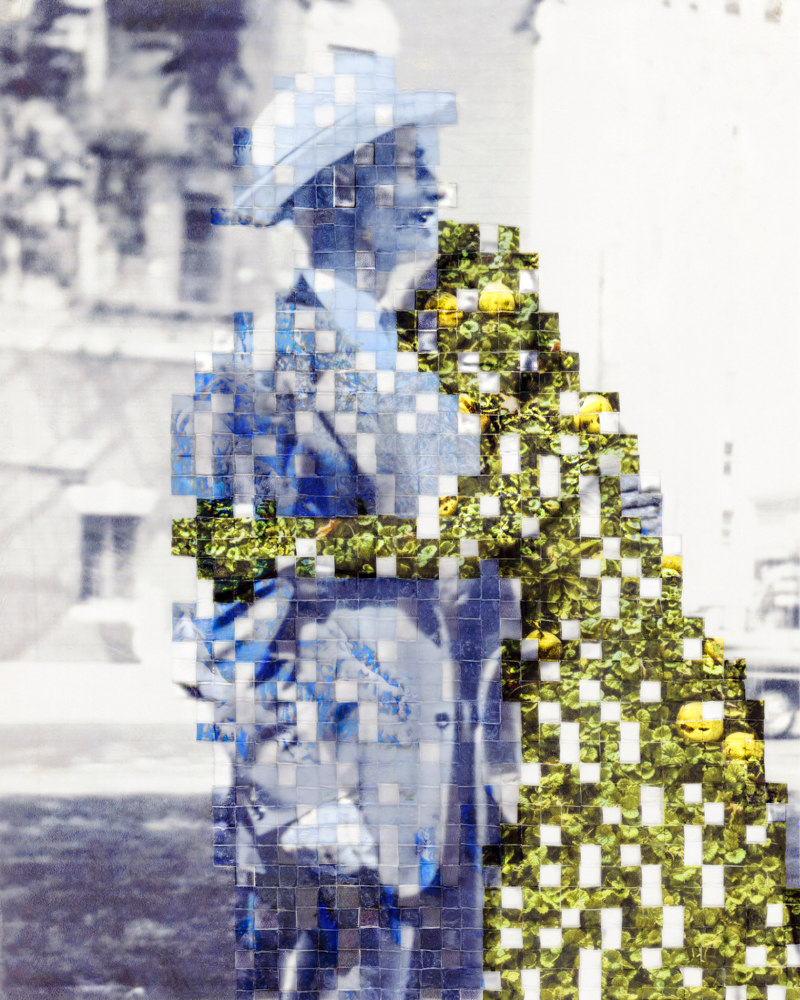

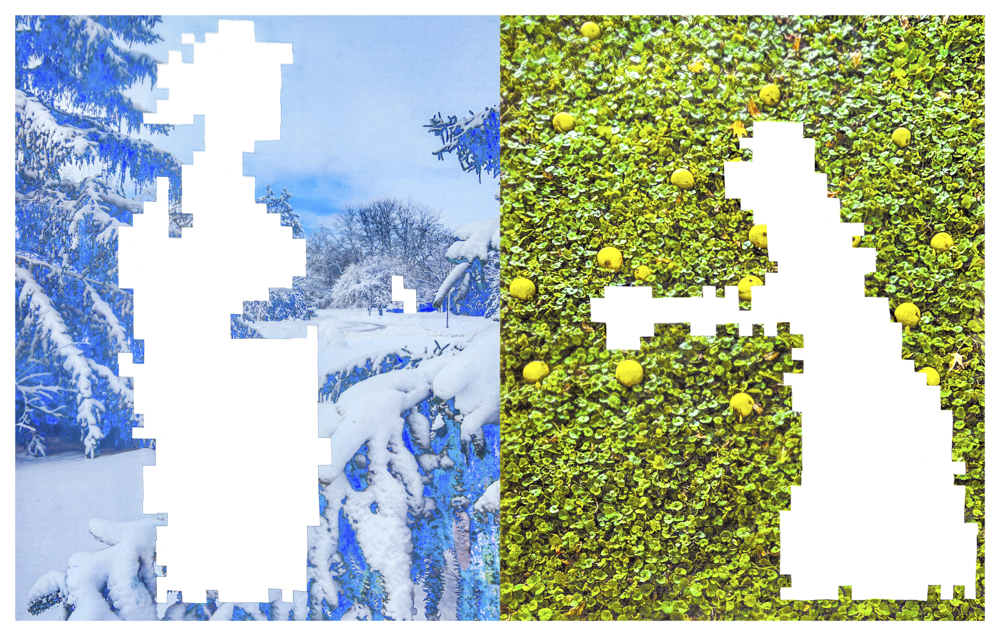

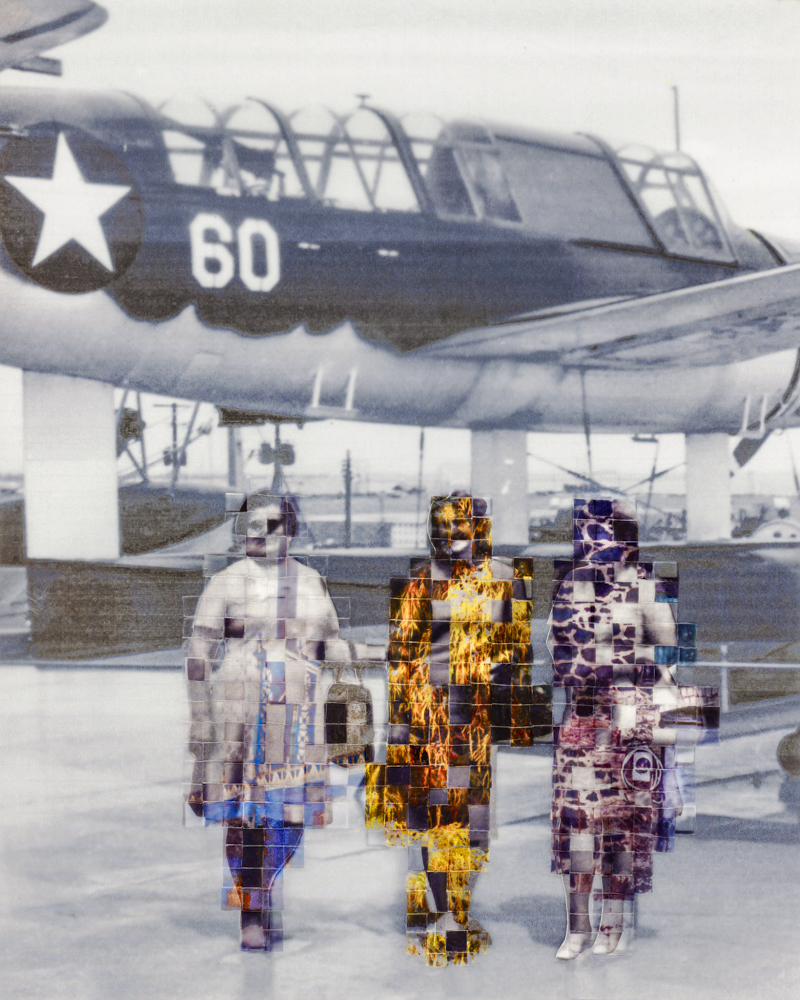

Ironically, Because It’s There started because of an idea that stuck around for me; it insisted, starting with Stein and her famous line “there is no there there.” She used it when recalling the occasion of trying to visit her childhood home and realized that physically, it was gone, and along with its absence, her childhood seemed to go missing too. I made it a point to be more aware of what I was picking up on around me, and another thing was Tommy Orange’s novel There There, also set in and around Oakland. It explores the urbanization of native lands and how that affects peoples’ identities and sense of belonging (or not). Then Radiohead’s song “There, There” came up, and that song relates the same phrase to individual felt experience and its “thereness”, but it also uses the phrase as the sort of tired idiom we might hear when upset. From there, I continued to push forward; and once, when reading, saw a quote from the French film director, screenwriter and photographer Agnes Varda: “If we opened people up, we’d find landscapes.” That also stuck, and near that time, I also heard, for the first time, a song by Public Service Broadcasting: “Everest.” It contains samples from the 1953 documentary, The Conquest of Everest. In it, a man asks: “Why should a man climb Everest?” Another answers: “Because it is there.” It was then that I knew I needed to work with that and started to experiment with my ideas. I ended up gridding, coding the grid (to the Morse Code to “because it is there”), and hand-cutting small squares of combinations of photographs, using all of the “keeps” and “discards” to make new photographs that both visually and conceptually parallel how we make and use memory to create our constantly fluctuating truths and realities while keeping in mind the idea of a “thereness” that insists through time.

EK: What relationship does memory play within your practice?

LB: Memory has a huge relationship to my practice. I think that although my work can certainly be identified as mine by people who have become used to seeing it, it does not always look the same from project to project. It does all circle the same concern(s), and one of those, if not the strongest and most important, is memory. I surround it in different ways through what I make. And really, it is the construction, fluctuation, and subjectivity of memory that I seem to be most curious about and wanting to make work about right now. Currently, I am reading Tim Carpenter’s To Photograph is to Learn How to Die, and it hits on many of the things that I have been thinking about, plus more. There is a thought he includes from Paul Valéry that struck a chord right away: “Memory is the substance of all thought. Anticipation and its gropings, desire, planning, the projection of our hopes, our fears, are the main interior activity of our being” (21). I find this fascinating, and it is something that I think about a lot in relation to making work and in general. Sensory intake and perception, cross temporality, and the continual building of individual experience combined with all things on the outside and how they collide and affect what we call memory is a major driver in why and how I make my work.

EK: Is there a specific image that is your favorite or particularly meaningful to this series?

LB: I don’t really have a favorite, but if I had to choose one that is particularly meaningful to the series, I guess it would be Swimmers because it is the first image that I made for this project that worked in all of the ways that I had hoped. This project started to come together more after I made it, and from it, I was able to tweak things more effectively, develop a consistent process, and move forward with making new images.

EK: Can you tell us about your artistic practice?

LB: Sure. My practice involves many things; a lot of it I call “cross-training”. These things might seem unrelated to what I make to some, but they all play into what I am making. I have a background in literature, language, and psychology and have always had a heavy interest in music, and all of those disciplines are a part of my cross-training, especially reading and listening to music. I am also curious by nature; I am one of those people who asks the whys, hows, whats; it can sometimes drive my friends nuts, but this curiosity also drives my practice. I use photography itself in a number of different ways, and one thing I practice is to photograph what is around me daily, with whatever camera I have handy. I collect the images, and this collection results in a sort of visual brainstorming and language. These images sometimes end up in future work, sometimes not. Other times, I will plan, seek out, and make photographs to use later.

Most always though, I end up experimenting to develop processes that attempt to bring subject-matter, form, and process into relation with one another. I tend to call this “matching.” It means that when I have an idea, I will begin by brainstorming, researching, and then use trial and error until I make photographs or photographic objects that visually match what I am thinking about and am hoping to relay in a final image or object. Along with that, the process that I use often relates to its subject-matter as well. It seems complicated, but it is how it always seems to go without me thinking too much about it. I will often reuse photographs from other projects for new work but in different and sometimes subtle ways; I see it as relating to those concepts that I am most curious about: memory, truth, and ultimately, insistence.

EK: What’s next for you?

LB: I am trying to focus on a few things. Right now, I am gathering ideas and thinking of some ways to start working on a new body of work, but at the same time I am starting to organize images and other related items for zine/book ideas. I continue to add to some of my already-in-progress projects as well and am in collaboration with another artist on some new projects. And, I am hopeful that a workshop Making Photographs from Photographs: Creative Methods to Enhance Your Visual Voice will run next summer at Maine Media Workshops + College, but dates and details haven’t been determined for that yet. Recently I was named a Photolucida Critical Mass Top 200 finalist and am now waiting to hear about who is selected for the Top 50 (fingers crossed, knock on wood). Earlier this year I was lucky enough to curate an exhibition, Distant Dialogues, for Float Photo Magazine with Micah McCoy and Vann Thomas Powell, two good photographer friends who are making lots of interesting work, and we are now looking forward to a couple of other curating opportunities. We have also been throwing around some ideas that are a sort of extension of that which is exciting and something to look for!

Epiphany Knedler is an interdisciplinary artist + educator exploring the ways we engage with history. She graduated from the University of South Dakota with a BFA in Studio Art and a BA in Political Science and completed her MFA in Studio Art at East Carolina University. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota, serving as a Lecturer of Art and the co-curator for the art collective Midwest Nice Art. Her work has been exhibited in the New York Times, Vermont Center for Photography, Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, and awarded through the Lucie Foundation, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass.

Follow Epiphany on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The PorchApril 28th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025