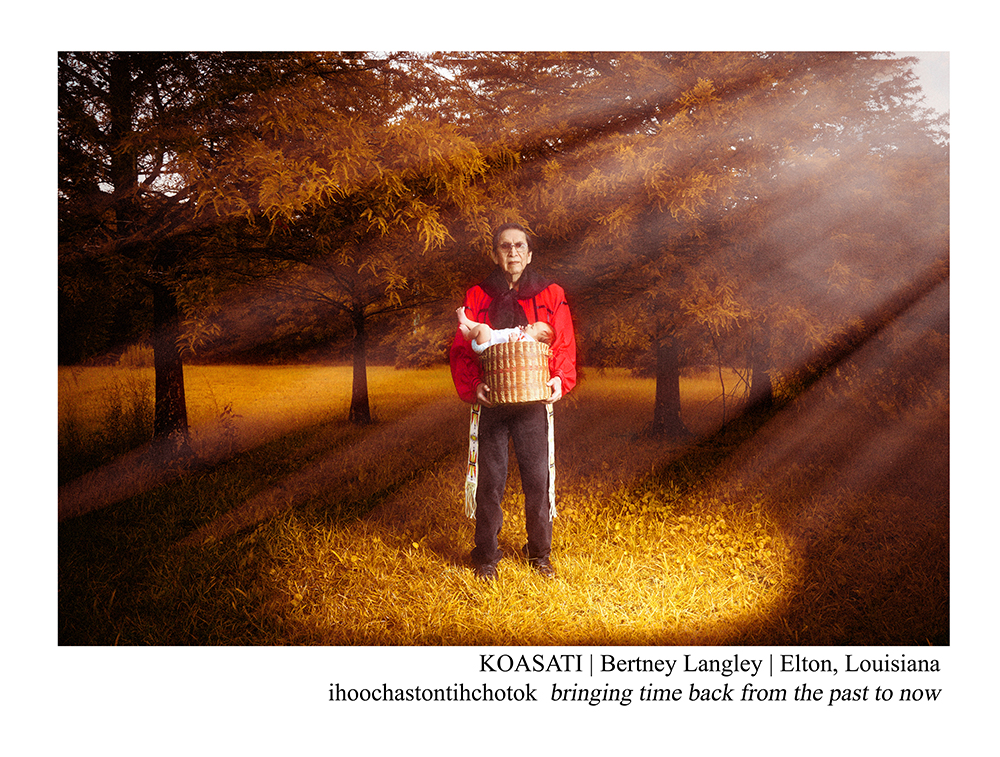

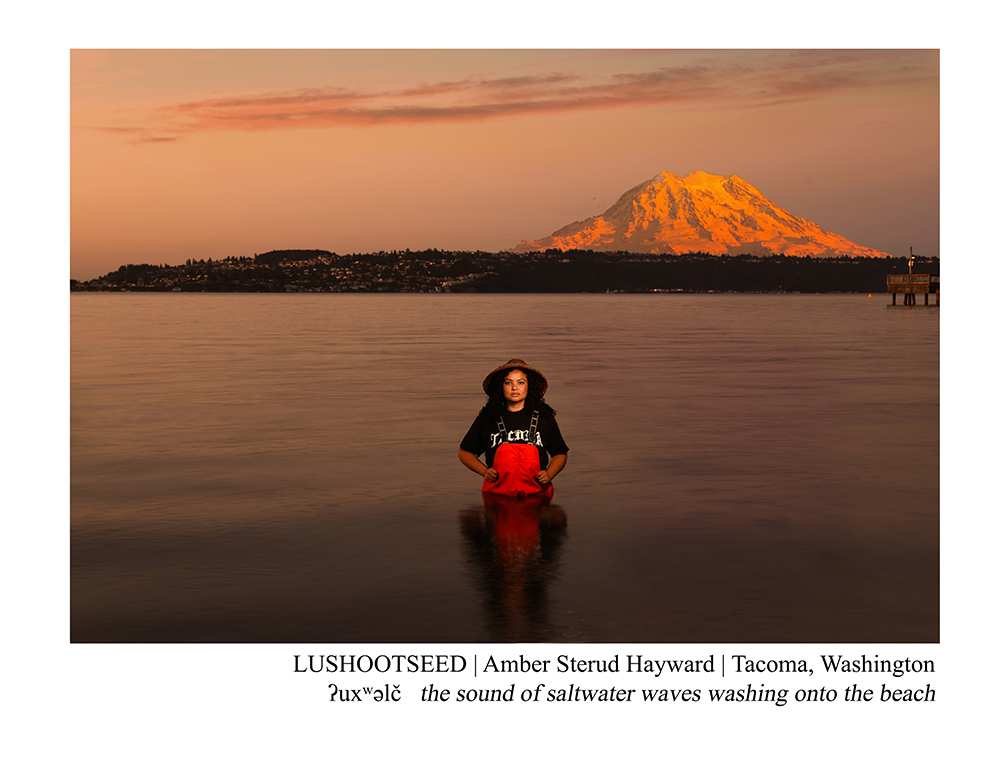

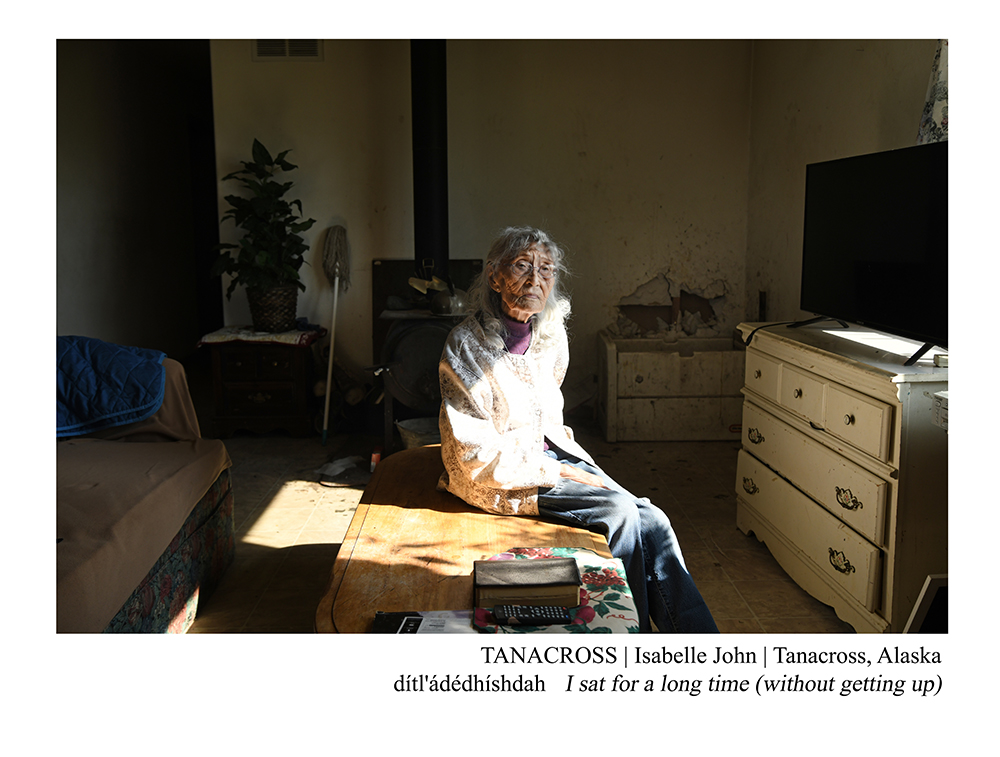

B.A. Van Sise: On the National Language

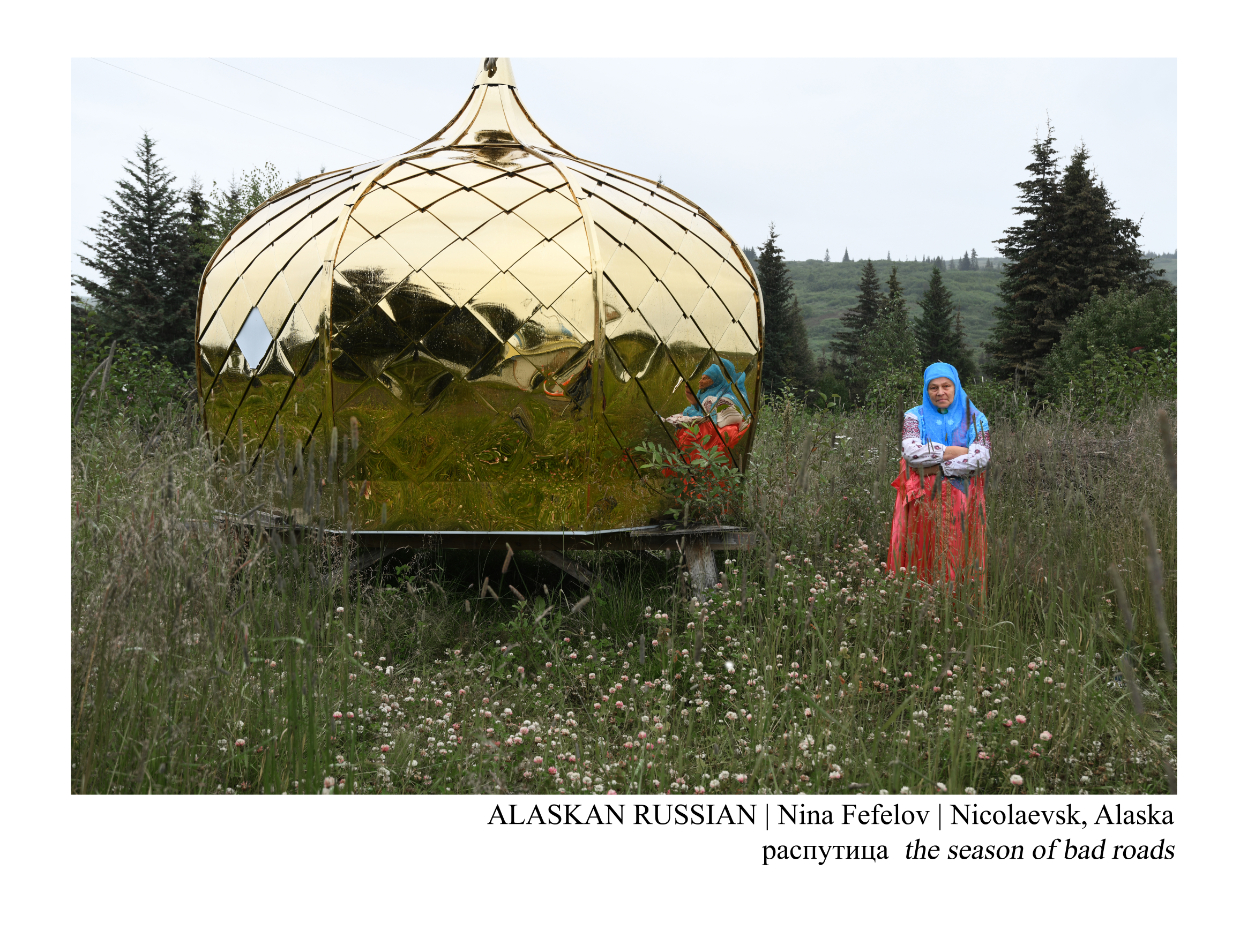

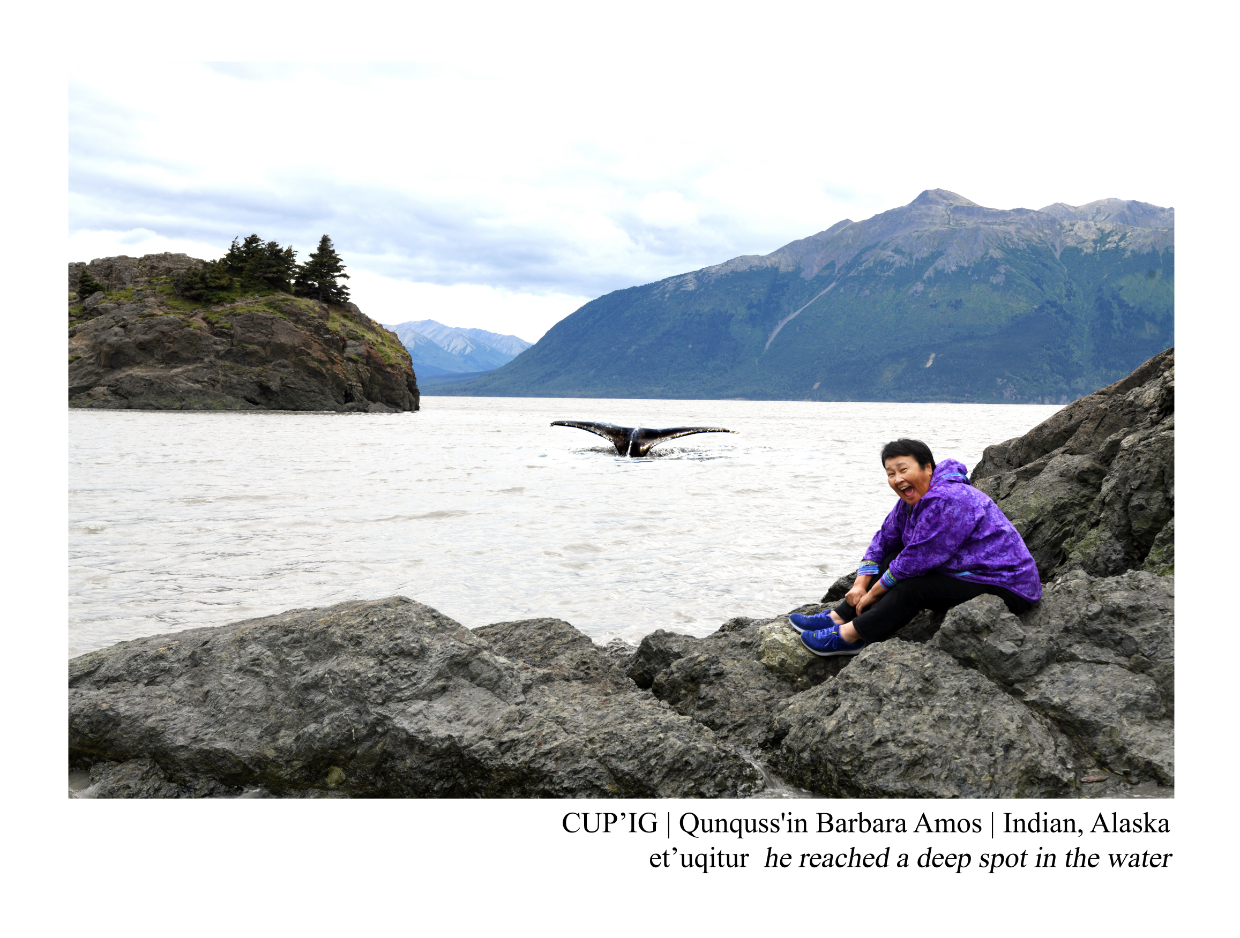

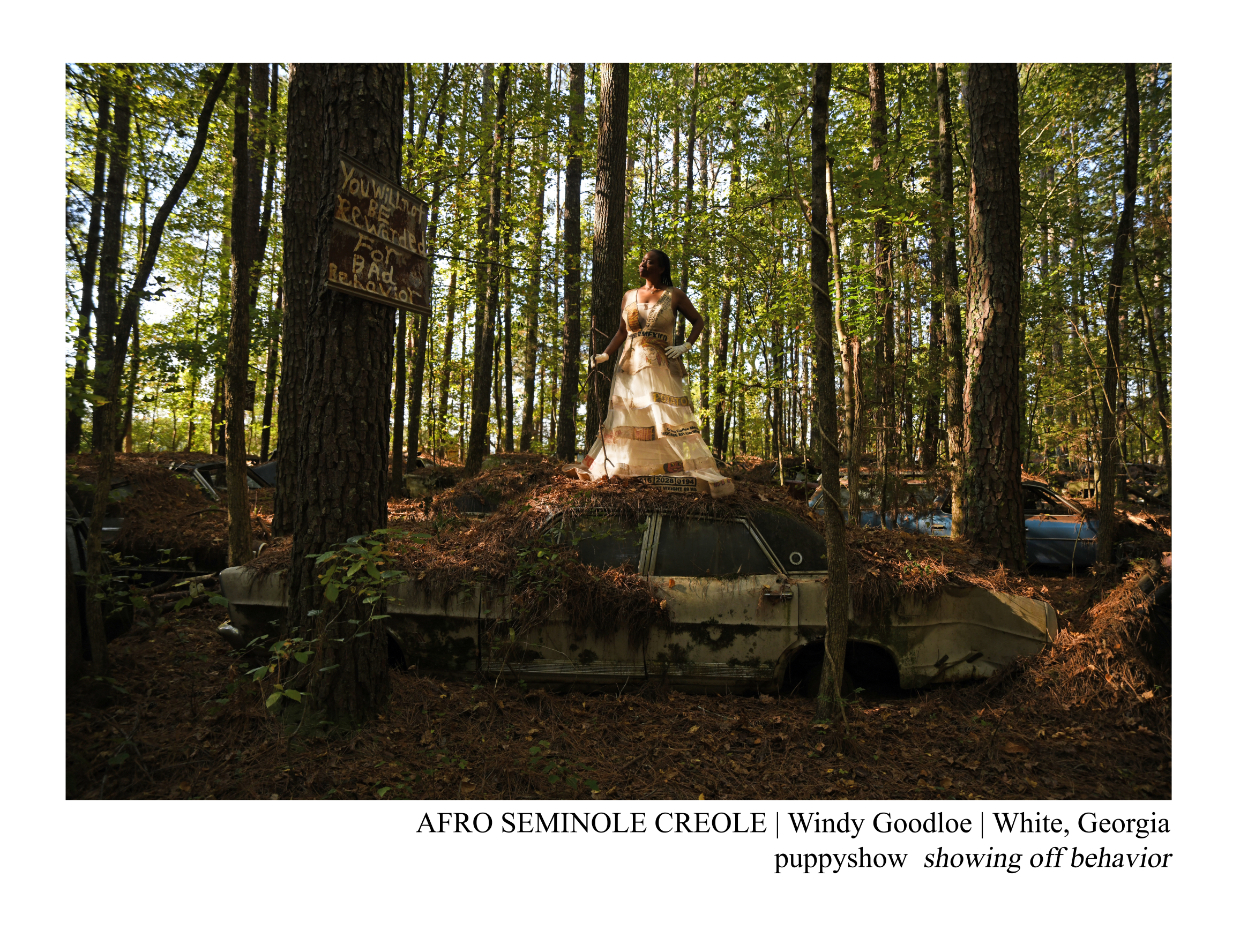

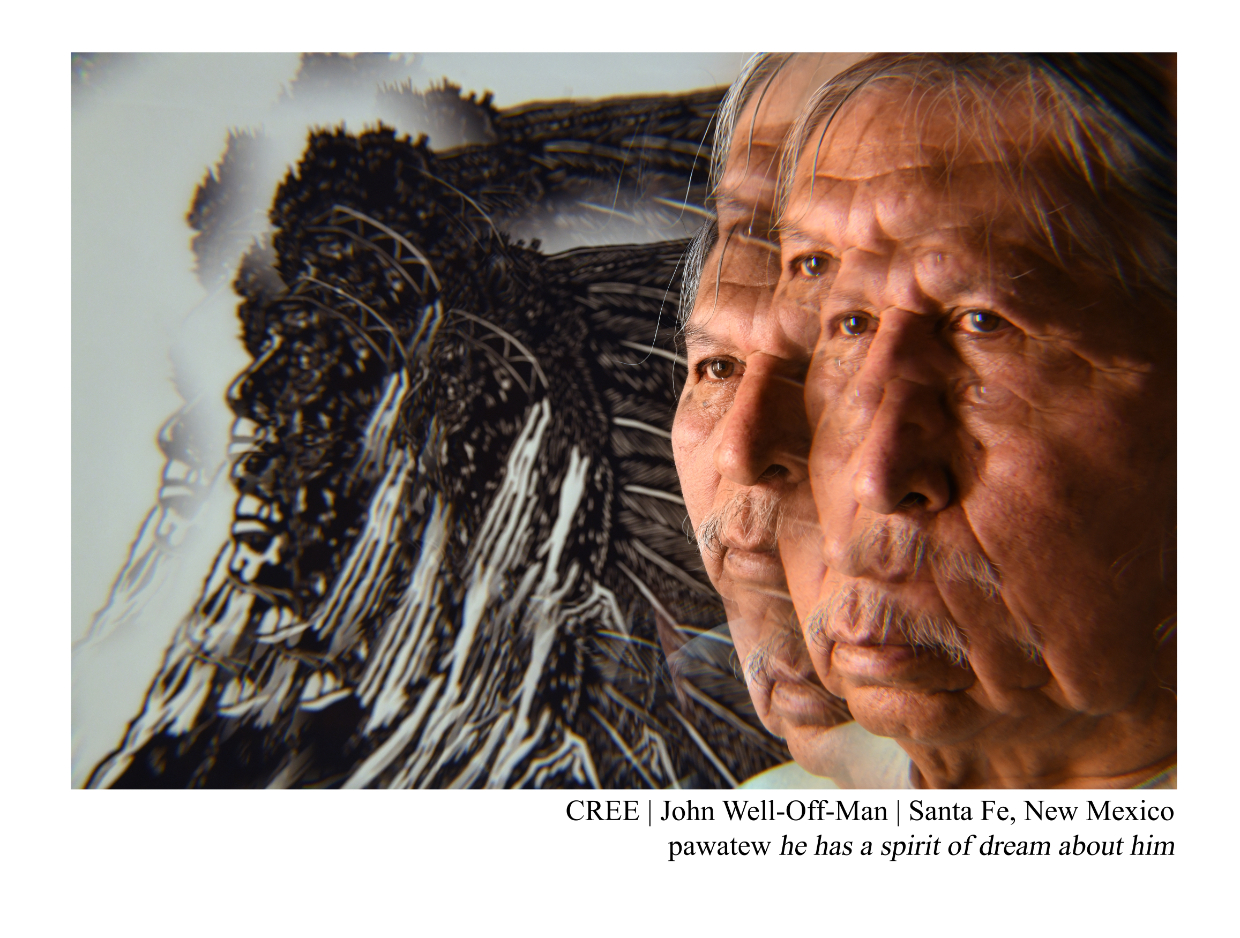

B.A. Van Sise is an author and photographic artist focused primarily on the intersection of language and the visual image, especially as it relates to American experience, creating books and exhibitions that largely feature images with textual pairings.

B.A. Van Sise is an author and photographic artist with three monographs: the visual poetry anthology Children of Grass with Mary-Louise Parker, Invited to Life with Neil Gaiman, and On the National Language with DeLanna Studi. In photography he has been a finalist for the Meitar Award for Excellence in Photography, and is a Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation grant recipient, a two time Prix de la Photographie Paris award-winner, a New York State Council on the Arts/New York Foundation for the Arts Fellow in Photography, and a winner of the International Academy of Digital Arts and Sciences’ Anthem Award for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. For nonfiction he has been a finalist for the Travel Media Awards for feature writing and is a winner of the Lascaux Prize for Nonfiction, and for poetry he has been a finalist for the Rattle Poetry Prize and Kenyon Poetry Prize, and a winner of the Colonel Darron L. Wright Memorial Writing Awards and the Independent Book Publishers Awards gold medal, twice.

Instagram: @b.a.vansise

SARA BENNETT: Thanks for talking with me. Should I call you B.A.?

B.A. VAN SISE: Yes. It is in fact my name. Everybody calls me that—friends, family, curators and editors, assistants and subjects but for some reason nobody believes me, even though they’re just fine with J.K. Simmons, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, P.J. O’Rourke, etc. It’s not a secret, it’s just ethnic and not preferred.

SARA BENNETT: I first discovered your work because we both have images in The Lonka Project, a photographic tribute to the remaining living Holocaust survivors. There are more than 450 images in that book taken by over 300 photographers. You were one of the photographers I looked up and I learned of several of your projects. We can’t possibly cover them all today so I want to focus on two of them: Invited to Life: Finding Hope after the Holocaust and On the National Language: The Poetry of America’s Endangered Tongues. There are 90 gorgeous black and white portraits in Invited to Life, but dozens more stories as well. Can you tell me how the series came about, how you found your subjects, why you don’t have portraits of everyone, and what it was like to spend so much time with Holocaust survivors. I’ve only photographed three survivors this past year and my time with each was so incredibly moving and meaningful.

B.A. VAN SISE: I sat with 140 Holocaust survivors over six years, which is 128 more than the dozen or so I originally pitched when I was working at the Village Voice—which is how it all started: in 2015 I was working at the Village Voice, the now of-blessed-memory weekly alternative newspaper in New York. Donald Trump had just begun his campaign for president and was speaking a great deal about what he saw as the blight of immigrants in this country: how they’re not sending their best people, how the immigrant class is full of rapists and murderers and so on. I pitched my editor at the time on the idea of doing a short series on refugees who’d made their lives in America, looking back on the whole of that experience. My original instinct was to do a series on Cuban refugees who’d come over after the New Year’s revolution in 1959, but I realized they just weren’t quite old enough to look fully back on their lives. I then turned to a different cadre: Holocaust survivors, who came in great numbers after the second World War and in particularly dire circumstances, especially strange strangers in a strange land: they practiced a minority religion, rarely had work experience, rarely had a word of English, and almost never had true networks of family. They’d lost absolutely everything. They’d been razed to zero. And then they showed up on our shores, frail and foreign and penniless; what did those subsequent lives entail?

The Museum of Jewish Heritage in NYC kindly obliged me by introducing me to a bunch of survivors but with a warning: you’ll meet these people and fall in love.

Well, Sara: I met these people, and I fell in love.

The 12 picture spread for the Voice, which more or less shuttered while I was working on it, turned to sitting with 37 survivors in the first grouping and about a hundred more that I met with while working on a Getty News/NurPhoto contract during the pandemic. I was running around photographing protests and shuttered stores and political rallies and then also filling my heart with survivors, who are really to the very last remarkable people who have an extremely hopeful view on the world.

I met with about 140 in total but included 90 in the end, because I like all my projects to be in multiples of 18: Children of Grass and On the National Language are 72, Invited to Life is 90, I think Memory Palace will end up being 56; part of that is size. The book is massive, 8” x12”, four pounds, the publisher spared no expense in putting together this 225 page book and there couldn’t have been any more. But also part of that is logistical: I knew that I’d have to leave something on the cutting room floor because it was overwhelming, because there were images of mine that were weaker or stories I told more poorly, or in the case of four of the subjects, serious doubts about the veracity of their status as Holocaust survivors that would have prevented inclusion. So, in the end, about a third of the people I got to sit with ended up consigned to memory.

SARA BENNETT: I know exactly what you mean about falling in love. I’ve been photographing women over the age of 90 who live alone and I’ve stayed in touch with almost all of them. As a matter of fact, yesterday one of the women I photographed invited all of the others to her home for tea and eight women over the age of 90 showed up. It was amazing. We have so much to learn from the old old. Did you stay in touch with any of the people you photographed?

B.A. VAN SISE: Yes, lots of them. About half of the Holocaust survivors have become memory since I met them, but I keep in touch with lots of them—I still know and visit with a lot of the poets from Children of Grass, I do a lot of public talks with the Holocaust survivors and we actually, legitimately, hang out too. I think about a dozen of the people I photographed for On the National Language came to the opening at the Skirball, and I just got a text this very morning from another letting me know he’ll be in New York around the holidays and asking if I’ll join him for a Knicks game, which will probably happen because while I care about the New York Knicks about as much as they care about me, it’ll be a pleasure to see him.

SARA BENNETT: Both Invited to Life and On the National Language have very powerful written elements. Do you consider yourself more a writer or a photographer? I used to be a writer but the more I photograph the less I want to write. Does that ever happen to you?

B.A. VAN SISE: I’m a poet and a photographer, and I think they’re the same medium. They’re the only two artistic media that require presence: a fiction writer doesn’t need to be there, Stephen King doesn’t need to hang out with clowns in the sewer to write It. And a painter doesn’t need to be there: Michelangelo didn’t need to die and go to Heaven to imagine the Sistine Chapel. But the poet needs to be present in their life, the photographer needs to be present in their life: physically, emotionally, all of it. Yes, I can push a noun against a verb to suit my purposes, but I just don’t see them as being that different in application.

SARA BENNETT: Oh, interesting. I think of photographing as so interactive and social but writing as a solitary activity so I never thought of poetry in that way.

B.A. VAN SISE: Poets, in my experience, have a culture very similar to photographers—there’s an experiential tack that’s pretty universal to them. I think there’s a time when your assumption would have been true—Thoreau writing at his pond alone, staring at ducks while doing the hard work of waiting for his mother to make him a sandwich—but in the contemporary world it’s different, especially with the rise of younger, so-called “stage poets” where there’s a little element of show business to it, too.

SARA BENNETT: On the National Language is such a beautiful book, both the photographs and the writing. I imagine it took a lot of research and seeking out subjects. How did that project come about?

B.A. VAN SISE: It wasn’t my original project. I was working originally on a thing called Sooners Later, which was about the Oklahoma landscape and the way its grass and nostalgic Americana is permeated with neon. They were nighttime landscapes, essentially, and I was getting pretty far along with it—my regular publisher and I had discussed it, I’d convinced poor Ben Rector to write a foreword—and then I got sideswiped by something better: I was out in Tulsa working on the project and on a free day had decided to take my three year old godson to the Cherokee Heritage Center (I am horrifying avuncular; he’s an enrolled Cherokee and I’ve been trying to stitch the tapestry of him with more colorful threads.) He was asleep in the back, I was bored in the front. Popping through the radio dial I ended up on some drive-time radio program which that particular day was featuring the actor Dwayne Johnson, promoting some film—I assume Moana—and he had this absolutely enchanting moment talking about how in spite of all his success, his wealth, all the cool things he gets to do, he wasn’t as connected to his Samoan heritage or his Samoan language as he wished and it was a bit of a hole in him. I’m a visual artist and an endangered language speaker with a degree in linguistics and there’s an old saying in theater that if a coin hits the stage, the audience knows by the sound of it if it’s real. Driving in that car that morning, I heard the coin hit the stage.

In the beginning I tried doing things the “right way”, which was absolutely the worst way possible: in an effort at propriety, I was reaching out to cultural associations, tribes, nations (in the case of the Native American languages) and really without exception they’d send me their most executive/”chiefy” looking man—and it’s a man—somebody who likes getting their picture taken. And somebody who was also, time and time again, a liar—people who couldn’t speak the languages, weren’t trying to learn the languages, etc. About five or six images in, though, I got hooked up with a language revitalizer out in Oklahoma who was a younger guy and it really turned the project for me: I realized the project was about younger folks and the future, more than the colonialist ideas of the past. But more importantly than that: a lot of the folks working to save these languages from the brink of silence all know each other. So I built this out the way I did Children of Grass eight years ago—personal referrals. I’d photograph someone working with ABC language and they’d say “hey, you know, I know a cool person who does cool stuff who’s working with DEF language, would you be interested?” And then it got to be like threading beads onto a string, one after the other, of cool people all over the country.

SARA BENNETT: You said the images in the book “are as collaborative as I could make them.” What does that mean exactly?

B.A. VAN SISE: In GENERAL the words are suggested by the subjects—they’d give me a few different poetic words they liked—and in GENERAL I’d try to come up with interesting visual concepts—but there’s definitely folks who came in with big ideas for both, and a couple where I came in with something and wanted to make it a reality. The two that come to mind for that are Yiddish, where I came in knowing Leo Rosten’s wonderful definition of schmutz from The Joys of Yiddish, and Nahuatl, where I was familiar with the Spanish missionaries who’d recorded these beautiful, epically long Aztec single-word poems and in both cases I approached the subjects basically saying “hey, here’s what I wanna do. Are you down?” But for the vast, vast majority of cases it’s the subjects doing the lifting on the language, and me coming up with visual images that I hoped would capture some of that poetry and maybe be compelling.

SARA BENNETT: Both the books we’ve been talking about have been published by Schiffer. I think almost all Lenscratch readers are interested in the entire process of getting a photo book published. I certainly am. Can you tell me about that process and anything in particular you think Lenscratch readers should know?

B.A. VAN SISE: Getting a photo book published is tough because it’s a money-losing proposition; if you pay a vanity press to do your book you’re going to lose money and tears on it, every single time. I have a remarkable relationship with the folks at Schiffer, who I jumped to at the absolute 11th hour while talking with a very, very big publisher about doing Invited to Life, which already had two exhibitions lined up. But they’d sent me a book to review for the New York Journal of Books called Backroads Buildings by Steve Gross and Susan Daley and I really admired their production values. There are absolutely challenges with going with a smaller publisher: both of my two books with them have sold out on Amazon on release day, it can be a challenge to get magazines and newspapers to look at it as seriously—but at the end of the day you want work that will last, and it’s absolutely impossible to overstate what a beautiful job I think the Schiffer team has done with both my books.

SARA BENNETT: You’re right that your books are really really beautifully done.

B.A. VAN SISE: It actually creates a really fantastic sales gap. Invited to Life had about a dozen articles about it in pretty mainstream media, and few of those articles really drove book sales. On the National Language has gotten a pretty phenomenal amount of attention, and I don’t know what the sales numbers look like but I bet it’s similar. A photo book just isn’t as attractive in the abstract. But when they have me do book events? Or when it’s in a brick and mortar shop? Forget about it. I doubt I’ve done a book event for either book where it didn’t sell out because people can hold this big, heavy, tangible thing in their hands, see what a great job the Schiffer folks—and it’s them, not I—did with it. I did a book talk yesterday and they had 75 copies of On the National Language for the about fifty people I spoke with, and they sold out. A photograph is the theft of time; put another way, a photograph is a form of magic. And magic is always better when it happens in your own hands. Same reason why I hold little stock in these “online exhibitions” that are popping up everywhere now; a photograph is a physical thing. A website is not a big, real print you can almost step into. A book is not a blog post.

SARA BENNETT: I’m sorry I didn’t ask you about your entire oeuvre. But is there anything you’d like to say a few words about?

B.A. VAN SISE: My usual advice to young photographers and young poets—and I teach a lot of workshops on both, separately and simultaneously—is usually the same they give to budding priests: if you can imagine yourself doing anything else, do that. Isn’t it interesting how these art forms, the art of looking, the art of observing, the practice of being as much in the world as you —isn’t it wonderful how it is, in its way, a religion?

SARA BENNETT: I wouldn’t call it a religion but I think your advice is spot on: try to find a way to follow your passions and if your passions don’t pay, then find a day job that frees you up to follow your passion.

B.A. VAN SISE: I worked—I feel like this is everybody’s favorite fact about me—as a corporate executive for a few years. Was very successful, too: working for a man I still admire, I built a company so big that it caused its sale to a larger rival (a multimillion dollar purchase from which I received nary a cent, alas), and then as the vice president of a private jet company that flew around billionaires and mega-celebrities, where I was absolutely miserable: everybody there acted like Gordon Gekko. An old girlfriend—also admired—talked me into quitting it and going back to photography. I took a 95 percent pay cut and have ever since enjoyed a 100,000 percent increase in happiness. That was 12 years ago. The private jet company, I just found out, puts all my books on the table in their lobby waiting room.

SARA BENNETT: I wish I were in L.A. so I could go see the exhibition of On The National Language at the Skirball Cultural Center. It’s up through March 2, so plenty of time for Lenscratch readers in that area to go see it. Congratulations on the exhibition, your newest book, and thank you so much for talking with me.

B.A. VAN SISE: The pleasure is decidedly all mine.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph YOU Took in 2025, Part 4January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 5January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025, Part 6January 1st, 2026