Smith Galtney in Conversation with Douglas Breault

Smith Galtney was first a writer, and then a photographer. Words and images are often at odds with each other, leaving a moment in between where ambiguity fizzles into its own daydreaming world. The tired saying that “a picture says a thousand words” raises the question: how important are those thousand words in conveying an image’s meaning? Galtney flexes the skills that all good writers and photographers share—paying close attention. His photographs embody the presence of the spaces he explores without being tied to a specific idea as his muse. Galtney observes peculiar patterns of aging, human interactions, and subtle humor, using them to explore the mystery of what we’re all actually doing here on Earth. He doesn’t offer answers, but I sense he has a few ideas. If photographs are evidence, then what are they evidence of? Galtney revels in this question by photographing anything and everything, returning to his desk like a writer to consider: why take a photograph?

Galtney does not over explain his photographs. He is a storyteller, but his photographic series do not follow a typical linear structure. His portraits position the subjects with a misty confidence as if they might even see you looking back at them. His photographs exude an ease and admirable simplicity that is untainted by the influence of social media. The photographs have a tangible substance that defies a fleeting Instagram persona. There is enduring weight to his timeless portraits, as opposed to the hollow, redundant world of the internet and its mirror. The portraits serve as a means of connection, resembling an affectionate conversation where a camera is casually left out on the table.

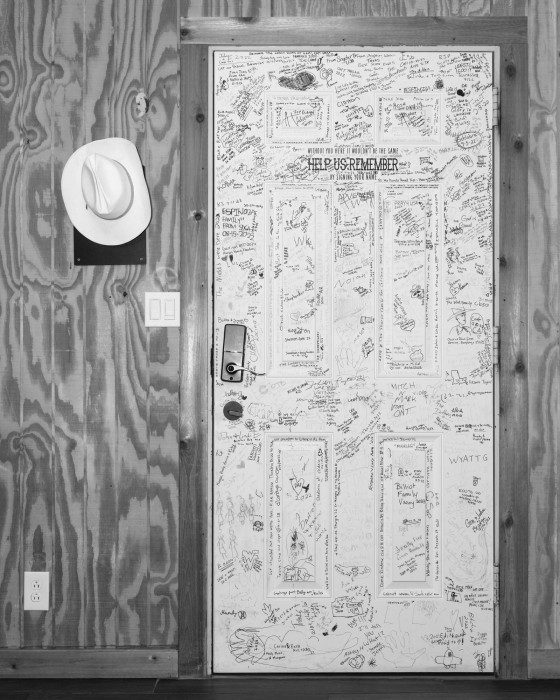

The photographs in his various bodies of work come together fantastically to illustrate the precariousness of the human subject as time unfolds slowly. A movie buff, Galtney draws on the vanity of filmmaking to create tension through composition and lighting. A fragment of a scene before the other shoe drops. His body of work titled Greenville contains nods to film noir drama and voyeuristic allusions to sex and absurdity that bring tension to the plot. While photography has always had an element of performance, Galtney guides the camera’s frame around the scene to echo the curiosity of existence in its many iterations of humor, history, and quiet musings.

There seems to be no subject off-limits in your photographs. What do you look for when you’re out in the world with your camera?

Anything and everything. Great light and color. Cool settings and details. People who have a distinct look and give off a unique energy. I’m pretty omnivorous, really. Maybe a little less so nowadays, just because I’ve taken so many pictures at this point and I’m trying to sort through and work with all I have instead of acquiring even more. But I always have a camera with me and feel anxious when I don’t. I can’t stand missing an opportunity! Often when I’m driving, I will pass something that looks interesting or beautiful – like a sign or a patch of light or a field of dead sunflowers – and I’ll keep going and try to convince myself that it’s not special. Then about a mile or two on, I’ll realize that I can’t live with the potential regret, so I’ll finally circle back and take the damn picture. Those shots rarely end up on any short lists – even when I take them, it’s like “yup, I knew this wasn’t worth it” – but at least I can move on with some peace of mind, knowing I at least made the effort. And of course, there’s always that one time when it actually is special and totally worth it.

It’s funny how the pictures I just happen upon, the shots that feel kind of knocked-off and throwaway in the moment, take on a greater resonance than the ones I run after. Back in January 2020, I took our car through the wash late one night and the suds jets splashed this perfect, day-glo flag across the window. I snapped several pictures and that was that. I didn’t like it much at first. I wasn’t used to working with colors that garish and it was a couple years before I made a print I was happy with. Now people love that picture. It was in a group show at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art. That’s why I hate not having a camera with me. You never know when a little mundane observation might lead to something bigger, something wonderful.

I’d say the only thing that’s off-limits is if a person looks compromised or feels looked down upon in some way. Which is not to say I’m opposed to anything unflattering. (My family can vouch for this, believe me.) But if there’s a detectable or unavoidable lack of dignity or self-possession, that’s no good for me. And I won’t bother anyone if they’re working. And sometimes I’ll get shy and wait too long and they’re gone. I used to take pictures of people more surreptitiously – go for a more journalistic “shoot first, ask later” approach. I guess I thought that was more authentic or something. But after some uncomfortable encounters that made me question everything, I started asking first and that felt so much better. You can still get something honest and I enjoy the sense of connection. People are genuinely touched by the request and the whole exchange feels generous, even when they say no.

What inspires you outside of photography that impacts your work—like books, music, or people?

I’d say the majority of what inspires me is outside of photography. I listen to music and watch movies and read books much more than I look at photographs. Music is HUGE for me. Bowie, Bryan Ferry, Prince, Madonna, Pet Shop Boys – that’s my Mount Rushmore, the end-all/be-all reference for anything I do creatively. Recently I’ve been playing Brian Eno’s “Discreet Music” and Terry Riley’s “Descending Moonshine Dervishes” a ton. They’re both really long pieces, spacious and immersive, and anytime I get too sucked into Instagram or whatever, they bring an instant rush of calm and clarity. Another big influence this year is Jon Savage’s book The Secret Public. It’s this incredible history of how LGBTQ+ performers shaped pop culture from the late ‘50s through the late ‘70s. I was reluctant to start it, just because I’m such a pop-culture junkie and I assumed there’d be little in it that I didn’t already know, but I was immediately sucked in and learned all this new stuff and got lots of ideas for pictures. As for movies, I just watched Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. It’s a really dark psychological thriller from 1960, about a killer cameraman who films people as they’re bring murdered. The color and composition are ridiculously mesmerizing, and the story itself is about photography, with all these great melodramatic lines like “everything I photograph, I seem to lose” and “the lights dim too soon, they always do.” When it all comes together like that, I get super-excited and buzzed for weeks.

But obviously photography is a big inspiration, too! Peter Hujar & David Armstrong & Jack Pierson are my forever Gay Holy Trinity. Nadia Lee Cohen and Michael Bailey-Gates are currently blowing my mind. And I’m beyond blessed to have a rich network of friends and mentors who are not only generous with their time and insight but also a lot of fun to be with. One coffee date with any of them is often just as – if not more – galvanizing than any work of art.

What advice would you give someone interested in developing a sense of intimacy in their portrait photographs?

In short, just put the camera aside for a moment. That can be really tricky, though, because it feels so counter-intuitive to everything you’re trying to achieve. When someone comes to my studio, I’ll make a point of talking with them for a while before getting started. It breaks the ice, you get to know each other a little better, and I also get a chance to observe and note their default conversational postures, so then I’ll know how to suggest poses that’ll look natural. But once the shooting starts, things can get a little tense and clinical. You’re futzing with the tripod and obsessing about exposure and suddenly your subject is all twisted up like a pretzel, because you’ve told them to turn their head toward the window and move their shoulders toward the doorway. That’s when it’s a good to take another breather, just chill and talk a little more. Almost immediately, they’ll slump back into a unguarded state and you get exactly what you’re after. If you start chasing after something, you run the risk of overdirecting and that’ll suck the life out of anybody. A friend once looked at some selects from a shoot and said I should be mindful of everything “outside the frame.” Which sounds like a wanky “art school” thing to say, but it’s a handy mantra, a nice reminder to pause and be patient. And if that all fails, just hang out more. One of the best assignments I’ve ever been given was to spend an uninterrupted 24 hours with someone. With that degree of concentrated time together, intimacy is a given.

Where do you want to see your work go next?

Well, I’ve been writing about this every day lately. I just started grad school, so I’m very much in “disrupt the process” mode. I’ve long been a very impulsive shooter – out and about with my camera, taking in the world as I see it – and now I’m making constructed narrative-based images, shopping in thrift stores for props and clothing, playing around with character and gesture and background. I’m also doing some video, which has been a little alarming because it’s made it very clear how much Instagram has gotten us all in a vertical frame of mind and I’ve had to basically retrain my eye to see in a widescreen, horizontal format. All in all, I’m hoping to step away from the more traditional, representational aspects of my work, add more color and artifice and humor to the mix, make it gayer and more cinematic and over-the-top. A book is definitely on the horizon, but I’d also love to open up the still image by experimenting with sound and installation. Reading The Secret Public, especially the parts about gay life in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, made me wanna poke fun of masculinity, too. Back then, something as simple as a limp wrist was a disgusting affront to American manhood. And it still is in a lot of ways. So all I really want to do is make gorgeous, exquisite portraits of limp wrists.

Smith Galtney is a Maine-based multimedia artist and storyteller who uses photography, writing, video, and performance to create narrative-driven works that mix autobiography and fiction. A graduate of New York University, the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies, and the International Center of Photography, he’s taught classes and workshops at Maine College of Art and Maine Media Workshop + College, and is currently studying at Image Text Ithaca, an MFA program at Cornell that brings together creative writing, visual media, and book design.

His photography has shown at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Grant Wahlquist Gallery, and SPEEDWELL Contemporary, where he’s also worked as curator and documentarian. A former entertainment journalist, his writing has appeared in The New York Times, GQ, Rolling Stone, NPR, Time Out New York, and The Village Voice.

Follow Smith Galtney on Instagram: @smithgaltney

Douglas Breault is an interdisciplinary artist who overlaps elements of photography, painting, sculpture, and video to merge spaces both real and imagined. His work has been collected, published, and exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (South Korea), Space Place Gallery (Russia), the Bristol Art Museum, the Rochester Museum of Fine Arts, Amos Eno Gallery, and VSOP Projects. Breault has been an artist in residence at MassMoca and AS220 and was awarded the Montague Travel Grant to study in London and Paris in 2017. Douglas is a professor of art at Babson College and Bridgewater State University, and he has been a guest critic at MassArt, Wellesley College, Kansas City Art Institute, and the Slade College of Art, among others. Douglas is the Exhibitions Director at Gallery 263 in Cambridge, MA. He received his MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University and a BA in Studio Art from Bridgewater State University, and he currently divides his time between Boston, MA, and Providence, RI.

Follow Douglas Breault on Instagram: @dug_bro

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025

-

Erin Shirreff: Permanent DraftsAugust 24th, 2025