BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-Kilroy

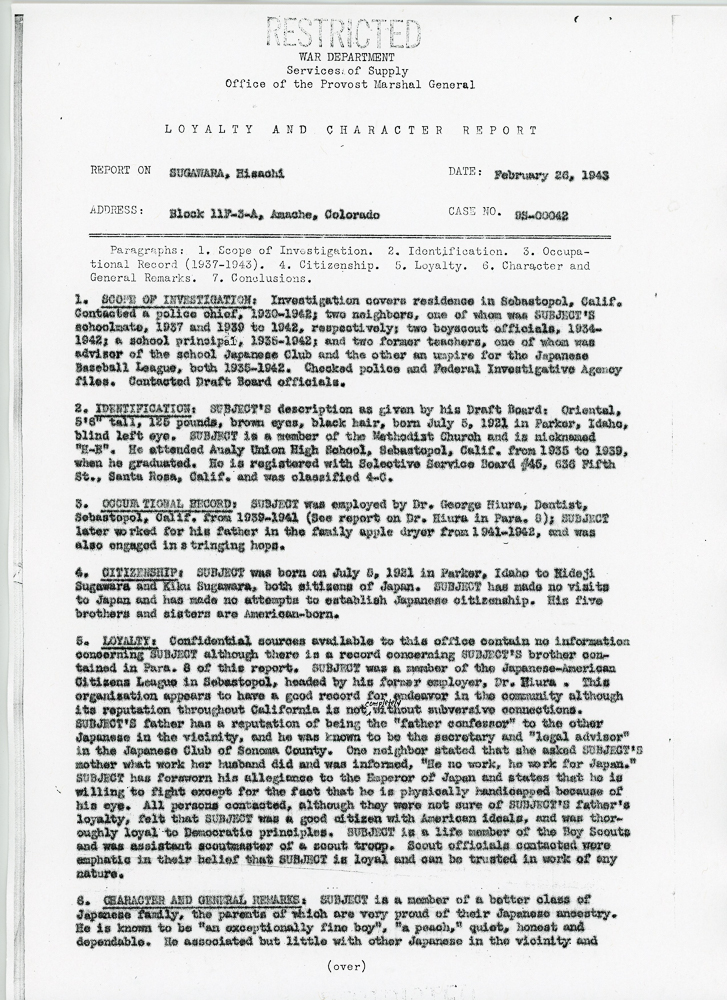

© Sandy Sugawara and United States National Archives, “Loyalty and Character Report” of Sandy Sugawara’s father, Hisashi Sugawara, dated February 26, 1943

Beyond the Photograph is a Lenscratch monthly series dedicated to helping photographers grow their artistic practices beyond the camera. Capturing images is just one small part of a photographer’s journey. In this series, we’ll explore the tools, strategies, and best practices that support the broader aspects of a contemporary art career.

Occasionally, we will check in with photographers who have undertaken projects involving extensive research. By exploring their projects and research materials, including primary sources, we can use their approach to research methodology as a guide. This will help compile a list of potential references for future or ongoing projects. These resources could range from government agencies and parks to networking with local officials, community leaders, teachers, professors, and students. It might also involve traditional methods like picking up the phone, or reaching out to non-profits and individuals who have experienced similar situations. By connecting these various resources, we can develop a comprehensive behind-the-scenes framework for creating impactful long-term photographic essays.

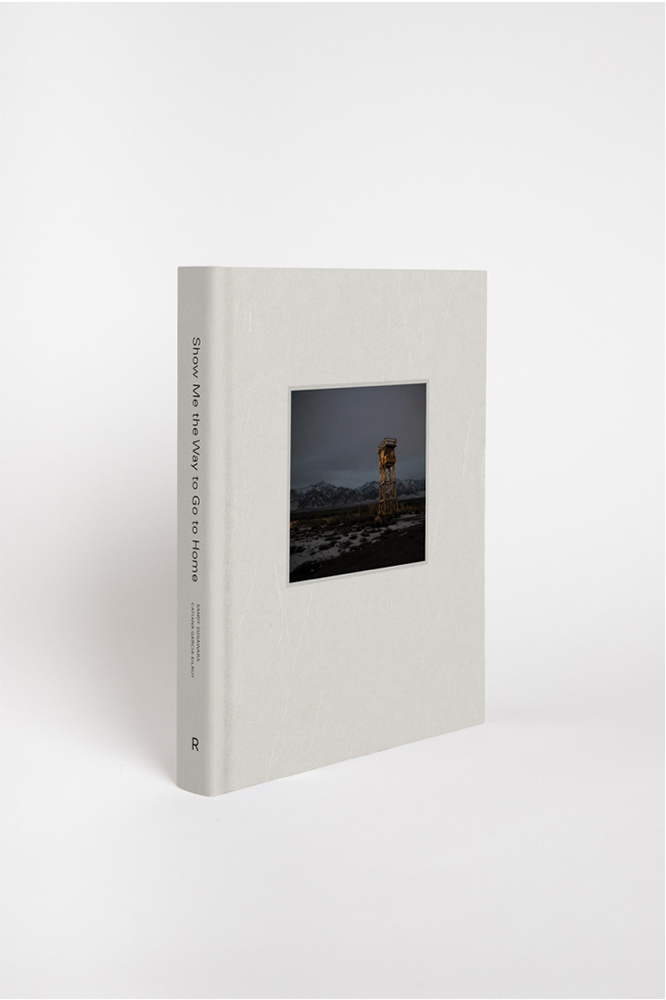

For this next installment of “Beyond the Photograph,” I asked Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-Kilroy to share their research process and sources for their collaborative project entitled “Show Me the Way to Go to Home” (Radius Books, 2022). The project is an immersive, visual journey through the incarceration camps that held 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. Photographers Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-Kilroy tell the story of each camp through original photographs, personal stories, and government documents. It’s a frightening tale of a society that failed to protect its vulnerable.

Information on Japanese American Incarcerated Families

My parents were among the 120,000 Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes and incarcerated during World War II. I first wanted to find out what their lives had been like in the camps. It turns out the War Relocation Authority (WRA) – the federal agency created to run the 10 mass incarceration camps for Japanese Americans – kept detailed records of everyone who was held in the camps, including what barracks they lived in, when they entered and left, their medical records, their answers to loyalty questionnaires, their religion, what publications they read, and if they were investigated. – Sandy Sugawara

The National Archives has created a web page called: “World War II Japanese American Incarceration: Researching an Individual or Family” to explain what is available.

On that page, the archive lays out the extensive information it has, how it is organized, and how to apply for specific case files.

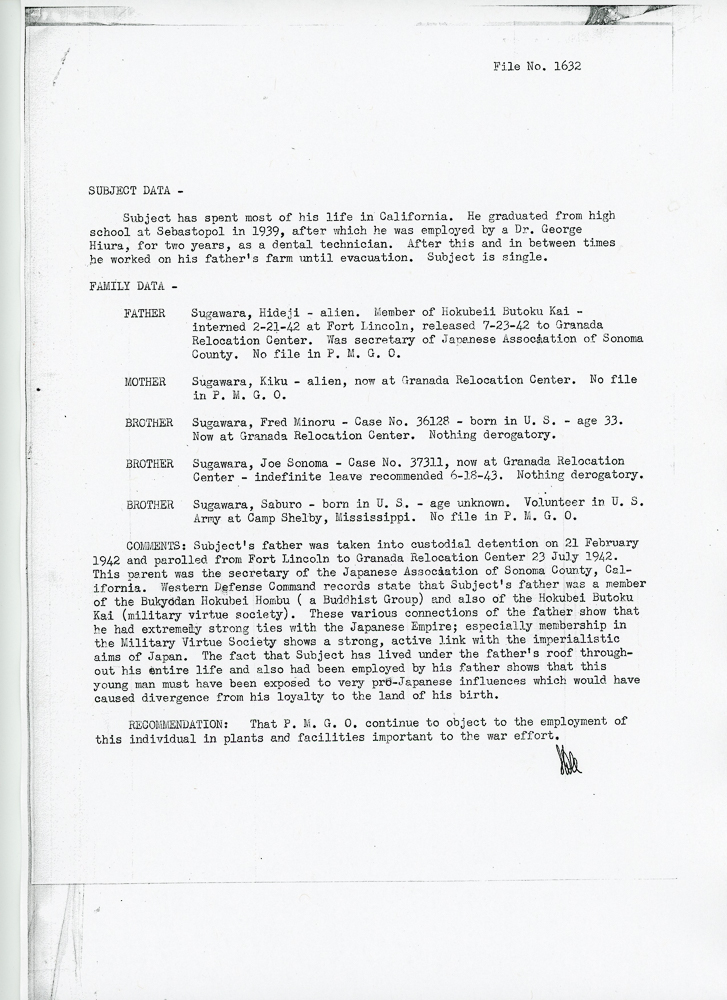

© Sandy Sugawara and United States National Archives, “File No. 1632, Subject Data, page from the loyalty investigation of Sandy Sugawara’s father, Hisashi Sugawara, 1943”

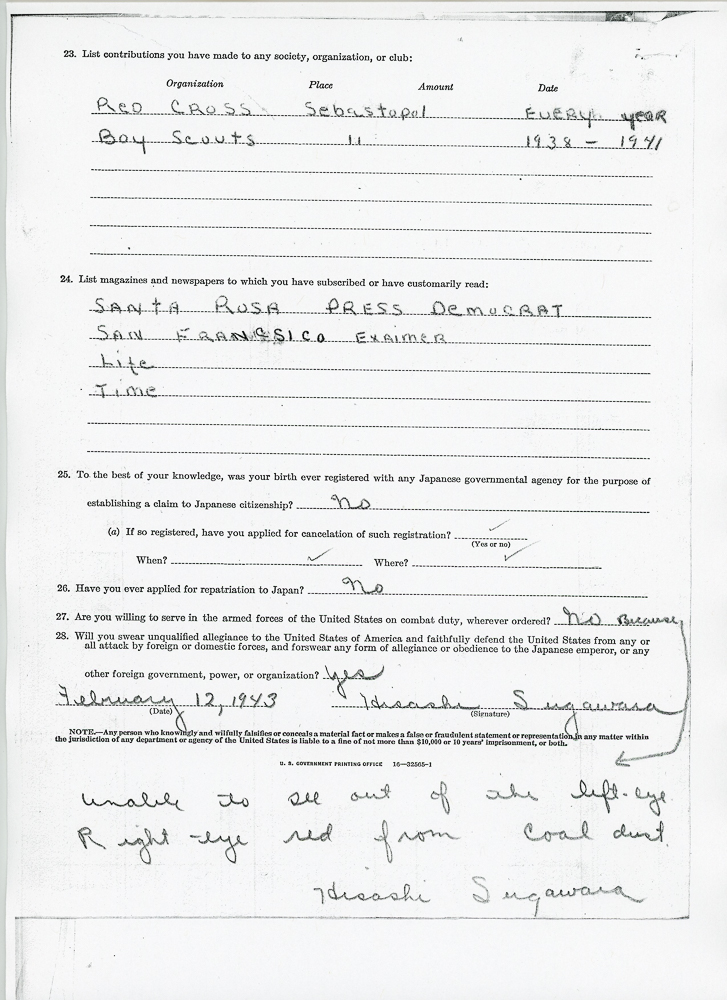

© Sandy Sugawara and United States National Archives, “Page from the loyalty questionnaire of Sandy Sugawara’s father, Hisashi Sugawara 1943”

I followed the instructions, and a few weeks later a thick case file arrived through the mail. Among other things, I found out about the poor medical care my grandfather received at the camp, which led to his painful death, and a loyalty investigation of my father, who was a teenager at the time. – Sandy Sugawara

After my dad died, my mom moved in with my family. For years she refused to talk about the Japanese American mass incarceration. But as she got older, she became upset about it. And on her deathbed, my soft-spoken mom angrily asked why Japanese Americans were singled out for mass incarceration and why nobody stood up for us.

After she died, I found this metal box under the foot of her bed. I had never seen it before. I opened it and was stunned to find many items my dad had kept from the time he was incarcerated in camp Amache — his autograph book, a photo of his dad’s funeral (his dad died in camp), and my grandfather’s health documents. – Sandy Sugawara

© Sandy Sugawara, photograph of Sandy Sugawara’s grandfather’s funeral from the project “Show Me the Way to Go to Home”

© Sandy Sugawara, photograph of Sandy Sugawara’s father’s wallet and contents from the project “Show Me the Way to Go to Home”

I also found my dad’s wallet– one he had used more recently. I was shocked to find, inside his wallet, meal tickets and other cards from Amache. He clearly had never gotten over his imprisonment there. I also found his Boy Scout card from back then. He was not active in the Boy Scouts after high school, but I think he held on to the card because he knew that when the government investigated him, the Boy Scouts vouched for him. I think it was important to him to know that someone had stood up for him. – Sandy Sugawara

Information on the Incarceration Camps

The National Archives also has an extensive collection of archival photos, documents and other original source material related to Japanese American Incarceration During World War II that live in the “Educator Resources” area. Links of primary sources go to DocsTeach, the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

National Archives and Records web page, “Japanese-American Incarceration During World War II: Primary Sources”

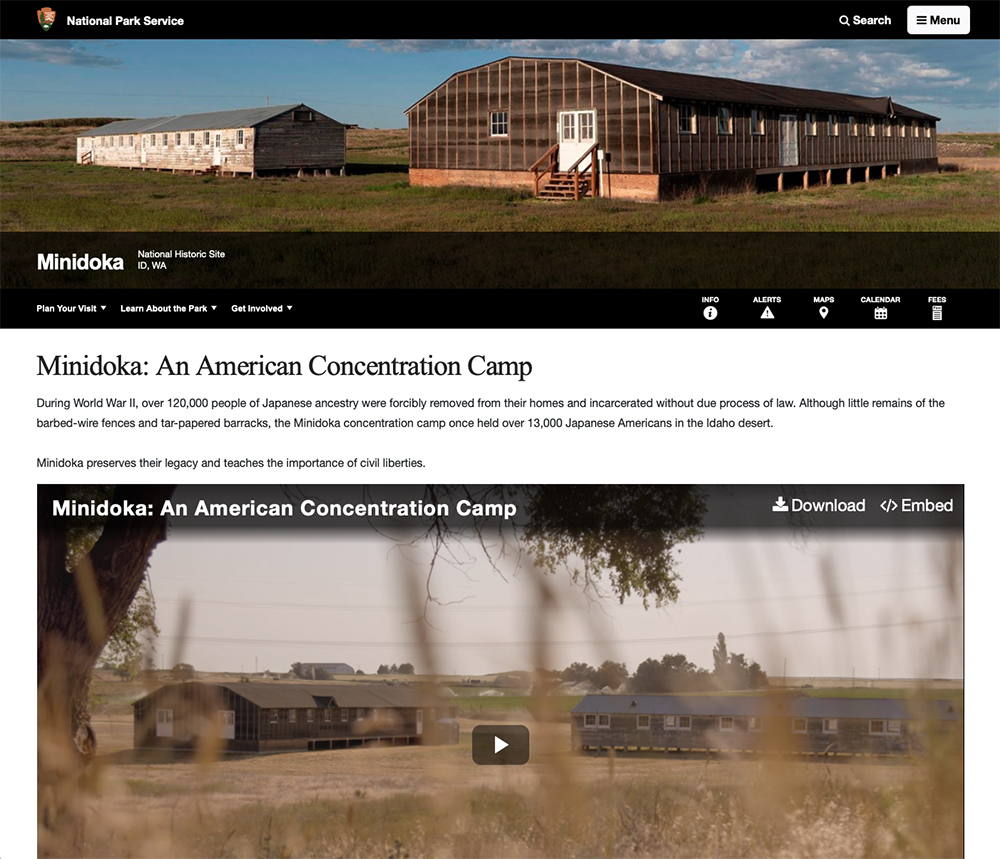

When Sandy and Catiana started the project about six years ago, three of the incarceration camps were part of the National Park Service (NPS): Manzanar, Minidoka and Tule Lake. Last year, a fourth site, Amache, was added. Park rangers at Manzanar, Minidoka and Tule Lake were contacted, and they were a wealth of information.

The other incarceration sites they researched and documented are not currently part of the National Park Service. However, each has an online presence that helped identify potential contacts. Through these connections, they were able to meet a variety of local officials and community leaders, including a retired mayor, high school teachers, university professors, librarians, researchers, and officials from private foundations—many of whom were experts on the camps.

Before the Amache site became part of the NPS, the primary experts on the Colorado camp included a local high school teacher and a Colorado professor. The high school teacher and his students were responsible for maintaining the site, offering tours, and helping to collect artifacts. He had volunteered for 30 years until the NPS assumed control last year. For each of the 10 camps they visited, they found dedicated supporters and historians.

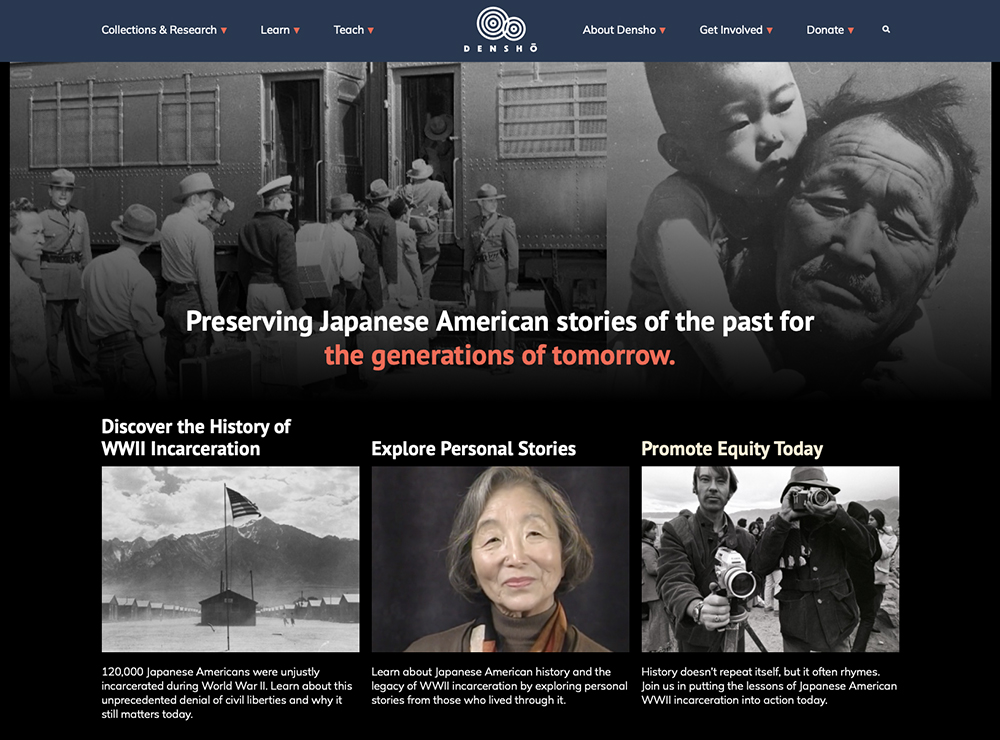

Non-profit organizations focused on various causes are also invaluable sources of information and contacts. During their online research, Sandy and Catiana discovered Densho, a website run by a non-profit organization. It features a vast collection of oral histories, archival photos, and an online encyclopedia that offers detailed information about each camp, notable Japanese Americans, national politicians, community leaders, and others who played a role in these events.

Densho is a non-profit organization whose mission is to preserve and share history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans to promote equity and justice today.

At many of the former incarceration sites, detainees or their descendants make pilgrimages to these locations. The groups that organize these pilgrimages for families and friends have proven to be essential sources of information. Many of these family groups also maintain websites.

A particular challenging, but rewarding process was to get permission to visit and photograph in Poston and Gila River camps, both on Native American reservation land. We were first introduced to them by Japanese Americans involved in the annual pilgrimages to these sites. We had to follow a well-structured process to obtain permission from the Tribal Councils. The whole process took over a year because it was in the middle of Covid-19. Once the lockdown was lifted and permission to visit granted, leaders of both camps went out of their way to guide us through the sites, showing us the most interesting landmarks and sharing moving stories about the relationships between both communities – Native Americans and Japanese Americans – at the time of the camps and how it evolved to present day.

Individual artists and activists are also great sources of information. Engaging with activists, authors, artists, poets, musicians, politicians, and non-profit leaders who have been advocating for years on these issues has been invaluable. These individuals, found through social media, reading, and attending gatherings about the camps, provided a wealth of information.

Developing personal relationships was particularly important as well as an enriching part of the experience. Catiana recalls meeting Hiroshi Shimizu who spent his childhood in several camps, including the high security camp at Tule Lake. He recounted details of his father imprisonment within that camp and having both his parents renounce U.S. citizenship under misguided advice. Spending time with Hiroshi helped her better understand the impact the camps had on Japanese American families, and he was helpful connecting her to other survivors and descendants. Those personal relationships helped Catiana understand how important it was to have someone outside the Japanese American community working hard to spread knowledge of this tragic event.

Catiana wrote in the Afterword of their book, “Show Me the Way to Go to Home:” The incarceration of Japanese Americans, like many other episodes of racism and oppression of minorities, was a human and civil rights problem. The story of the camps proves the importance of individual action. If those in the majority could have seen that an attack on their neighbors was an attack on the whole community, then many shameful events in history could have been avoided. This message is just as valid today as in the 1940s.

Sandy Sugawara, a Sansei or third generation Japanese American, is a journalist and photographer. She was an editor, reporter and foreign correspondent for The Washington Post and held a senior management position in a global broadcasting organization.

Her parents lived on farms in California, until they were imprisoned in Amache incarceration camp (Granada, CO.) during World War II. After being released from Amache, they resettled in Cleveland and Cincinnati.

Sandy was born in Cincinnati, graduated from Wellesley College, worked as a staff assistant to Norman Y. Mineta when he was a member of Congress, and then as a journalist in Washington DC and Tokyo. She currently lives in Maryland.

Her photographs are held in public and private collections, and her work has appeared in a number of juried exhibitions around the country.

Catiana García-Kilroy is a photographer and development economist. She studied History of Art at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid, where she was born, and Economics at Catholic University of Louvain la Neuve in Belgium. She worked as a stockbroker in Madrid and London and on development issues in Costa Rica, before moving to Washington D.C.

Catiana has developed a parallel career as a photographer, influenced and inspired by her interaction with numerous communities around the globe. She has worked on both personal and educational projects. In Costa Rica she was one of the founding members of the Foundation for the Social Link (Fundavinculo) dedicated to promoting art for development, and led two photography projects teaching photography to two groups of underserved youth that resulted in two photobooks with their photographs: “Southern Views” and “Transits.”

Her work has appeared in several juried exhibitions, including the “Global Images for Global Crisis” at the International Center of Photography in New York. Catiana is also working with Sandy on a project about Peruvian residents of Japanese ancestry who were kidnapped by the U.S. Government and incarcerated in Texas during World War II.

Jeanine Michna-Bales

After a successful 20-year career as a creative in advertising, Jeanine Michna-Bales transitioned to become a full-time artist. A visual storyteller working primarily in photography, Michna-Bales (American, b. 1971) explores the profound impact of cornerstone relationships on contemporary society—the connections between individuals, communities, and the land we inhabit. Her work sits at the crossroads of curiosity and knowledge, blending documentary and fine art, past and present, and disciplines like anthropology, sociology, environmentalism, and activism.

Michna-Bales’ artistic practice is rooted in thorough, often primary-source research, which allows her to explore multiple perspectives, grasp the complexities of cause and effect, and understand the socio-political context surrounding the subjects she examines.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025