Ernesto Cabral de Luna: Mining for Some Sort of Continuity

For the past few days, we have looked at the work of artists who submitted projects to our most recent call-for-submission. More to come in the future! Today, we have Mining for Some Sort of Continuity by Ernesto Cabral de Luna.

Ernesto Cabral de Luna is a Mexican lens-based artist working in Toronto. Utilizing both analog and digital processes, he pushes the boundaries of experimental photography by merging experimental techniques with sculpture and installation. Ernesto’s practice is deeply influenced by his material exploration, often printing onto unconventional and manipulated surfaces to emphasize the multi-dimensionality and materiality of the image. His work centers around altering perception through image manipulation – providing new ways to experience recognizable imagery in unconventional manners and outside of their intended purpose. Ernesto is interested in the fragmentary nature of memory, both individual and collective – and constantly seeks new ways to manipulate these alternative histories he is creating. Drawing from his immigrant experience, Ernesto explores themes of identity and representation, creating artwork that is relatable to people who feel like they are from two worlds in one sense, and from neither in another.

Follow Ernesto on Instagram: @abrokeniris

Mining for Some Sort of Continuity

This series focuses on the fragmentation that occurs within the personal, social and cultural identity of those living in exile. Central to this exploration is the fleeting nature of memories, whether stored in objects like photographs or in the mind, and how they construct a mobile, personal, and ephemeral archive that is fundamental to the construction of diasporic identities.

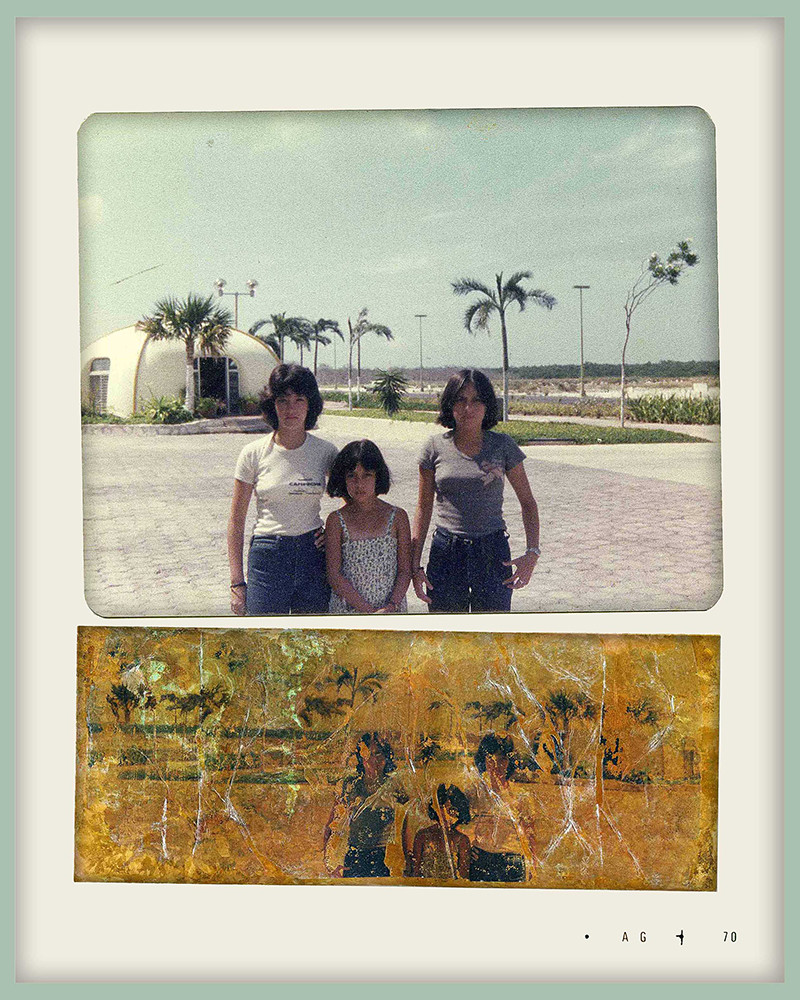

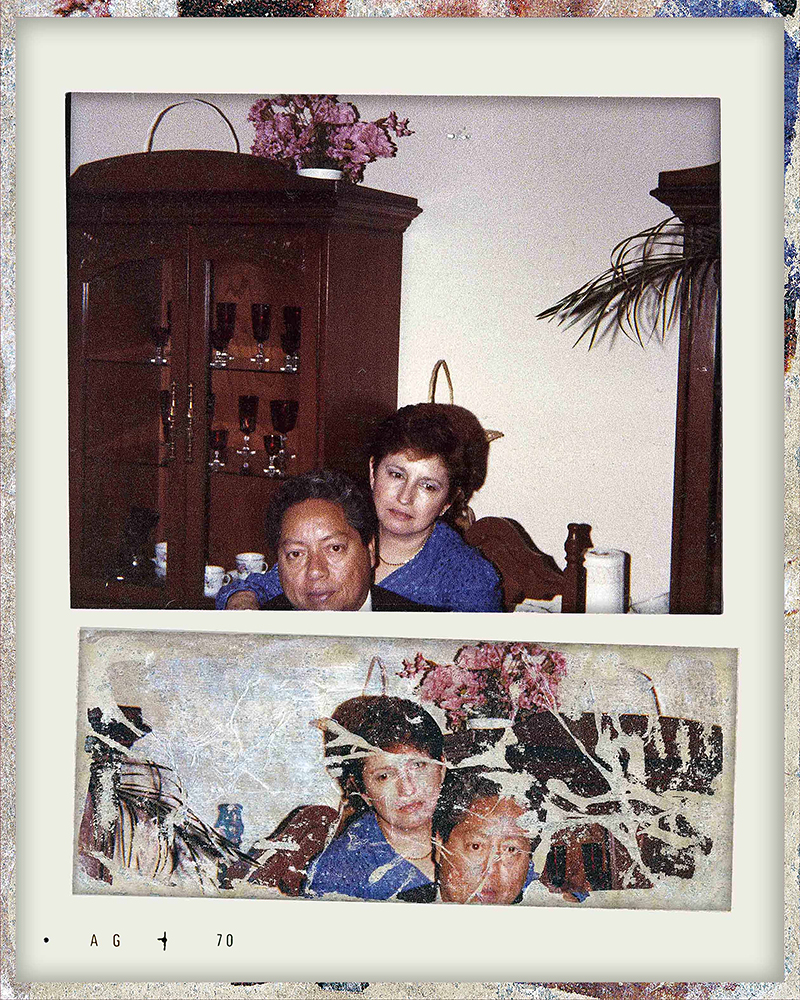

Appropriating archival family photographs becomes a poignant commentary on immigration and self-reinvention – challenging the notion of ownership over memories that are not one’s own. Through the process of an image transfer, an alternative reality is constructed in line with Alberto Manguel’s concept of the artist in exile, whose faithful memory betrays their country’s current reality such that “the exile sees the country as it never is… everything he does is colored by something half-remembered… it is a country drawn from memory, from things half-known or half-dreamt.”

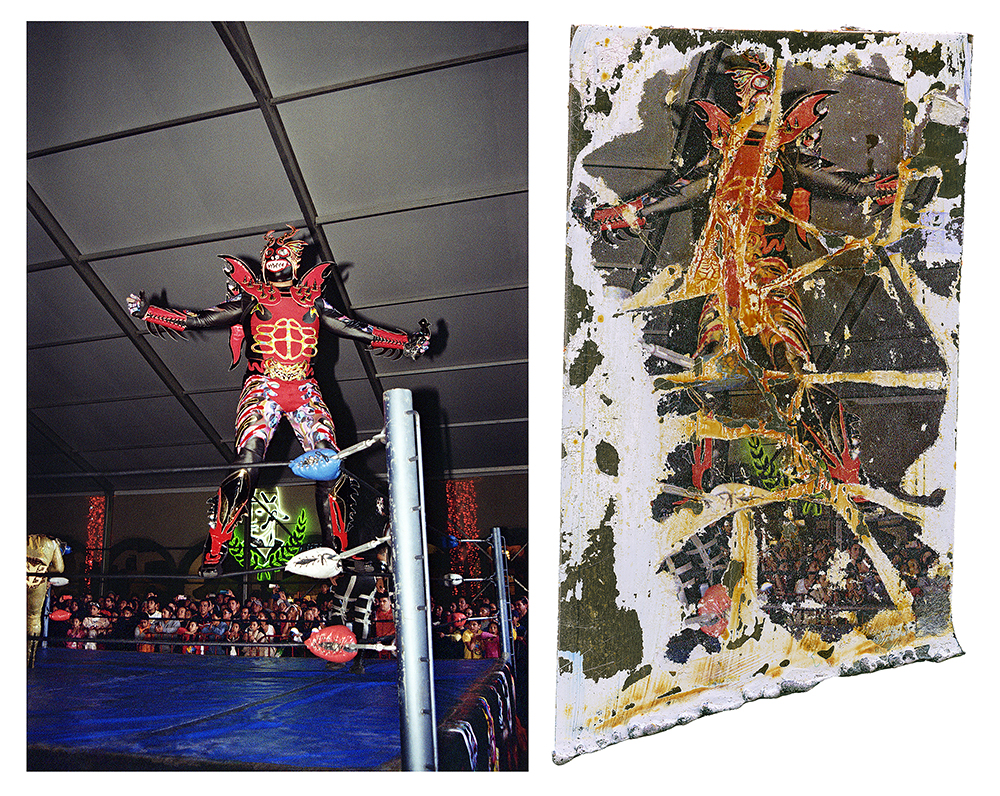

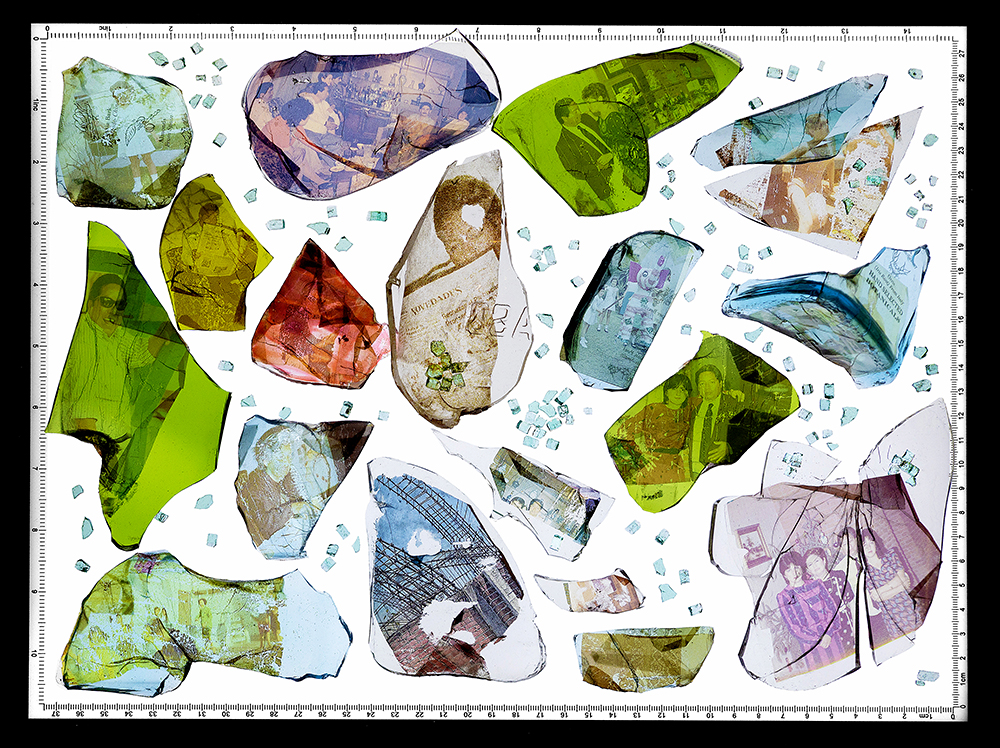

Fragmentation is a recurring visual motif throughout the series – evoking the puzzle-like way a diasporic identity is constructed. So too within the series, a single memory is literally split across several corrugated steel panels, or various copper plates, just as a lone glass shard recalls the moment it splintered from a larger whole.

Akin to immigration, to transfer an image is to displace it from its original source. A transfer is an almost identical version of the original, yet it cannot hide the fundamental changes it endured. The transfer is an eidetic image – remembered with accuracy and clarity, but subject to distortions. It is a mirrored reflection that has traded vibrancy and detail for textures and uniqueness. Traces of its journey are left visible through the scratches, rips and distortions produced through its translation and displacement.

Daniel George: What prompted you to create Mining for Some Sort of Continuity? Tell us how it all began.

Ernesto Cabral de Luna: This series originated as my culminating thesis project for my BFA in Photography at OCAD University. The catalyst was my interest in 20th-century Mexican Exvotos—devotional paintings on metal sheets used by an illiterate population to express gratitude for divine intervention. Growing up with Exvotos in my household, I was drawn to the way materiality shaped their narratives: rust bleeding through paint, flaking surfaces revealing metal, and bent corners marking the passage of time. Initially, I experimented with printing family photographs onto corroded metal, fascinated by the rich patinas of oxidized copper. Over time, I expanded my material exploration to include corrugated metal and shards of colored glass—elements inspired by childhood memories of makeshift security barriers in Mexico, where broken glass from bottles was embedded into walls as an ad-hoc form of barbed wire.

DG: In your artist statement, you speak of the “fleeting nature of memories” and share Alberto Manguel’s notions of things “half-remembered.” This makes me wonder more about your experience creating these images and working with the family archive. Has this project helped illustrate anything regarding your personal or familial identity? Would you mind sharing?

ECL: The materials themselves led me to use family photographs, making the project deeply rooted in my cultural identity. Copper, rust, concrete, and broken glass evoke the textures of home, and since I hadn’t visited Mexico in ten years, I turned to my family’s archives. Instead of focusing on my own childhood, I gravitated toward my parents’ past, appropriating their early memories and experiences. This sparked a beautiful chain reaction—images I selected would trigger recollections in my parents, leading them to share them in group chats with friends and family in Mexico, who would, in turn, recount their own memories. It was really special being able to hear an alternate perspective of the stories I grew up hearing, seeing the way moments can be altered in translation depending on how or who it is remembered by. I traveled back home the summer before my final year of university, determined to create my own memories as an adult, photographing places and traditions I remembered from childhood, as well as culturally significant events I had only heard about—cockfights, lucha libre, bull riding. Unexpectedly, I discovered new celebrations and locations my parents had never known, and it was my turn to explain to them about aspects of their home, revealing a dynamic between inherited and personal memory. While the work within this series thus far predominantly features archival family photographs, the image transfers onto corrugated metal primarily stem from my own photography. I found it necessary for my own perspective to be included in this conversation, and so I was drawn to imagery that conveyed memory not just through content, but through color, blur, and movement.

DG: I am intrigued by the ideas that you share related to the image-transfer process—particularly regarding those attributes of the distortions/scratches/etc. They have some semblance of the original yet they are distinctly their own. What led you to consider these visual attributes as a representation of immigration?

ECL: I think that for me, my family, and for many immigrants overall, home and family exist first and foremost as photographs. My connection to my culture has always been mediated by images, accompanied by my parents’ anecdotes. Over time, I assigned my own meanings to these photos, sometimes incorrectly—misidentifying people, places, and events. Not only was I living in Mexico vicariously through these images, but I was also fabricating my own histories to them. So if my parents aren’t around to tell me that the image I’m looking at isn’t of my great grandma—as I so certainly believe—but of her sister… who’s to say that my reality isn’t true? This reminds me of Gabriel García Márquez’s notion that “life is not what one lived, but what One remembers and how One remembers it in order to recount it.” Similarly, I believe images seek the materials they belong to. My process involves transferring images across multiple surfaces—paper, metal, glass, digital—until they find their final form. An image forced to migrate onto various materials will let you know which it prefers and when its found its home. Each scratch, distortion, and imperfection mirrors the way immigration alters identity. When I return to Mexico, I am “the Canadian,” marked by an accent, mannerisms, and clothing choices amongst other subtle cultural differences. No matter how much I retain of my heritage, traces of transformation remain, just as an image is forever changed by the surface it adheres to.

DG: Would you further describe the ways in which your background/interest in sculpture informs your photographic work in general? What do you feel the use of these “scrap materials” offers your images?

ECL: While I have worked with found imagery before, this was my first foray into sculptural installation and incorporating found objects. Having left Mexico at a young age, my trips back home have become quasi-archaeological journeys to unearth a precious resource: memory. These research-driven expeditions manifest in various ways: scouring my aunt’s house for family albums we had to leave behind, documenting everyday life that now feels foreign, and seeking cultural artifacts at any and every “tianguis” (flea market). For my family, these flea markets serve as spaces of cultural reclamation, allowing us to bring fragments of home back to Canada. However, as these spaces increasingly cater to tourists, I’ve come to realize that I, too, am now a visitor in my own homeland. This duality—belonging and displacement—led me to work with scrap materials. This is the reason I was drawn to corrugated metal, a material ubiquitous in Mexico but rare in Canada outside of roofing for backyard sheds, and I sought out used, rusted, and discarded sheets rather than new and pristine ones. These materials bear their own histories—each dent, bend, and patina holds an unknown past that I wanted to intertwine with my family’s narratives. Scrap materials challenge conventional ideas of value—what is considered disposable, what has already served its purpose. In my practice, I use color and texture to explore memory, dislocation, and distortion. A clean sheet of steel or a polished piece of glass wouldn’t carry the same weight as something that has already lived another life. The imperfections embedded in these materials mirror the way history, identity, and migration shape us, leaving behind traces that make us who we are.

DG: Since I am based in the United States, I cannot help but analyze this work in the context of current dialogue and policy surrounding immigration. To put it simply, it’s a mess and so many people are being negatively affected. I wonder how I would have responded to this work 6 months ago, or how we might talk about it 5 years from now. I am always interested in how projects like this evolve over time. I am curious to hear your perspective. Has your relationship to this work and its meaning transformed since its completion? In what ways?

ECL: This project remains in flux, and I see it continuing to evolve. While I’m content with where it is now, I’ve already begun experimenting with new materials and presentation methods. Originally, I envisioned the glass works being installed atop a brick wall sculpture, referencing the very inspiration for these pieces, and that remains an idea I want to realize. I also want to integrate more of my own photography, but I believe that artwork cannot be forced into something it does not want to be—this iteration wanted to primarily speak through family archives and I listened to its intentions. Over the past year, I’ve adapted this series for various contexts, including exhibitions, journals, murals, and billboards, each iteration revealing new dimensions of the work, aesthetically as much as conceptually. Hearing public responses has been insightful—especially seeing how, in the absence of explicit cultural markers, many viewers project their own family histories onto the images; while staring at a family photo, people see themselves, their parents, their home. I’ve also found that immigrant communities from the Global South recognize shared histories in the materials I use, drawing connections between regions shaped by colonialism and displacement.

Regarding the current escalating militarization at the borders, expulsion of people from regions, and continuing vilification of migrants—particularly in the U.S. and Palestine—it’s crucial to acknowledge that my work exists on the privileged-end of immigration stories. My personal experience, and therefore my artwork, cannot compare to the immediate threats faced by many others. Immigration inherently involves loss, but the loss accompanying a successful migration is vastly different from the suffering and violence of those who are denied refuge, equal rights, safety, and a sense of belonging. As an artist, I recognize the privilege of reflecting on identity without the immediate fear of deportation and for survival. It’s important to acknowledge how our paths and opportunities are facilitated by luck and circumstance, privileged by time, and dictated by the world’s governing bodies. For those of us who have secured citizenship, there’s an ethical responsibility to remain engaged and not turn a blind eye to the struggles of others simply because our personal journeys have reached relative stability. There are sadly far too many people who are too content to help shut the door to a country they themselves have immigrated to. Art can be a powerful tool for reflection, but its important as an artist to have perspective about situations, learning when to listen and amplify the voices of those whose safety and survival are at stake today.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026