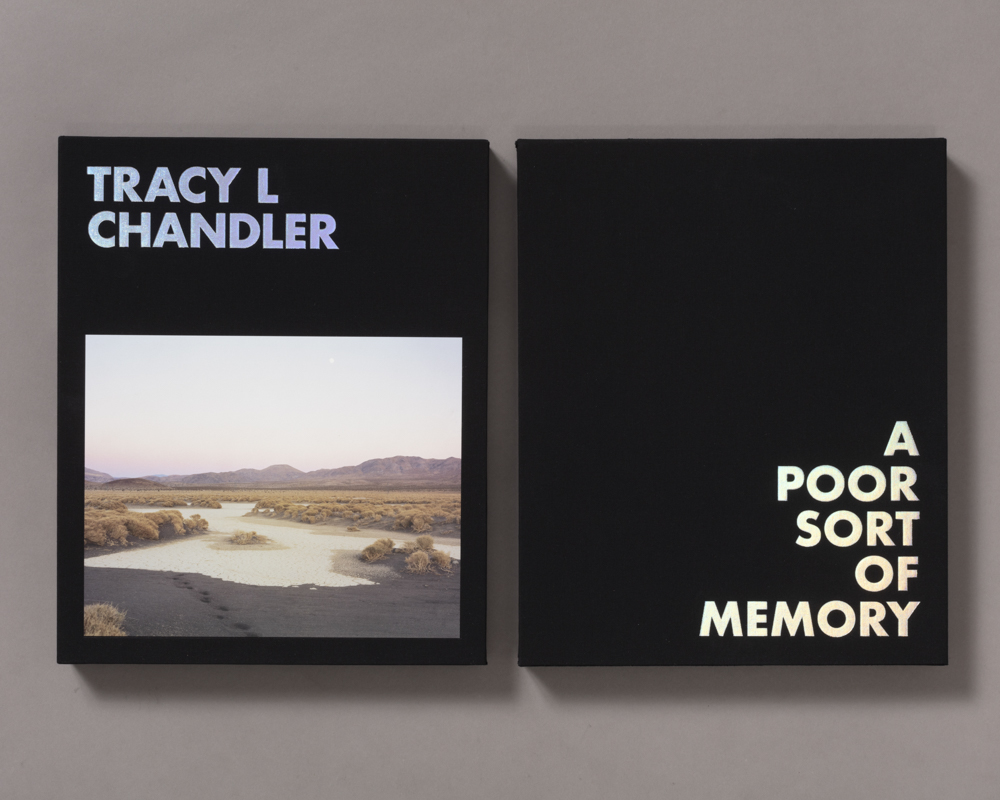

Matthew Genitempo & Tracy L Chandler In Conversation

Matthew Genitempo is someone I consider a friend. A friend whose work has long been an inspiration for me. When he and I started talking about doing something for Lenscratch, it was his suggestion that we put our work in conversation. Our books—Dogbreath and A Poor Sort of Memory—were made in different deserts, but explore similar territory. Both are portraits of coming of age through a tangle of grief, nostalgia, and the psychic residue of place. What started as a conversation about our individual processes turned into something deeper: a dialogue between two bodies of work that seem to be speaking the same language, just with different accents. I am happy to share this space with Matt and our conversation with all of you.

The following is a conversation between Matthew Genitempo and Tracy L Chandler.

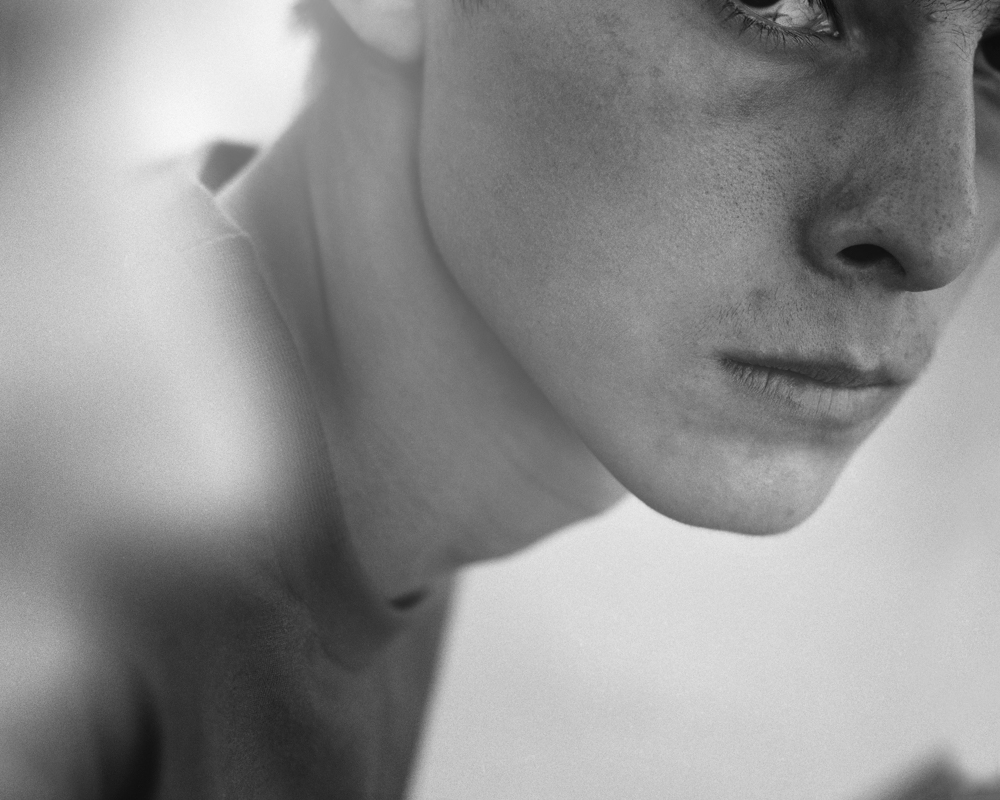

TLC: A few years ago you suggested I watch Lynn Ramsay’s Ratcatcher. (For those not familiar, in this raw late 90s film the child protagonist struggles with a harsh upbringing in a working-class neighborhood in Glasgow. It is sad and sweet and completely existential.) I watched it. I cried. Hard. Thank you for that. It completely resonated with my own upbringing and what I imagine to be a universal experience… the momentous and lonely challenge of coming of age. As I look at Dogbreath I see myself in your pictures. I’m wondering, do you see yourself? Did you go out looking with that in mind?

MG: Thanks for saying that—I’m really glad you enjoyed the movie. It’s been years since I last saw it, but I remember it leaving a similar impression on me.

These days, I never go out with any specific intention or idea in mind. Over the past few years, I’ve been fortunate to learn this about myself and my process. I just like to float through the world and let myself be drawn to whatever pulls me in. When I first started making pictures in Tucson, I didn’t have any real intentions either. I remember seeing younger people walking around in nearly 110-degree heat and being a little baffled. But it also made sense—I was the same way as a kid. Growing up in Texas, summers were brutal, but they never kept us inside. Maybe that memory was the jumping-off point, but I like to think that when I’m out working, I’m both uncovering a place through pictures and discovering pieces of myself along the way.

TLC: I totally get that. For me the process of self discovery is through reflection and interaction with the outside world. And I like the way you say “uncovering a place” like there are layers to get through to find the core essence…(of both the place and the self.)

Maybe I can see that process of discovery in your pictures…you are perforating boundaries. There are so many fences that we tentatively peer over and chain link that we timidly poke through, and then in some it feels more bold like we just hopped the wall and went right in.

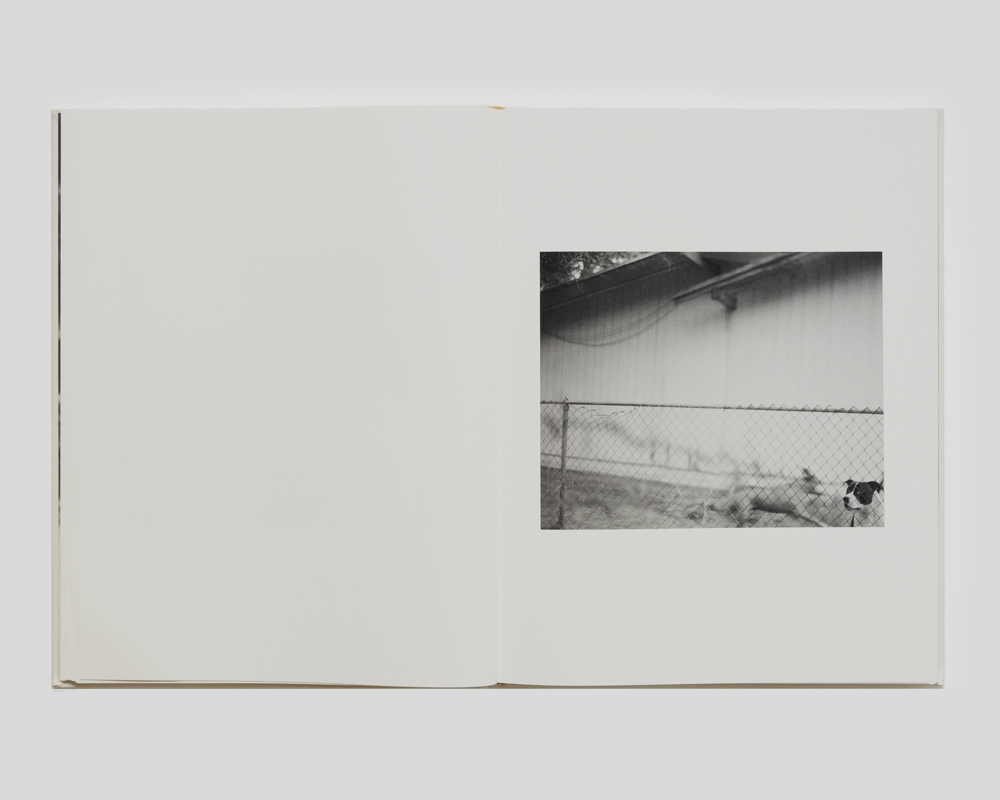

Did that feel bold at the time? Or more like you were invited in? Who/what did you find as you looked?…Do you feel you reached some sort of core? Can you talk about Dove and how he fits into this work?

MG: I’m not sure if anything ever felt bold. I remember feeling excited by the subject matter. I’m always drawn to movies that take place in suburbia, I think mostly because I grew up there and it’s easy to inhabit a familiar world. When the pictures were starting to come together and it was taking shape in that direction, I remember feeling like I was kind of making my own film that was set in suburbia.

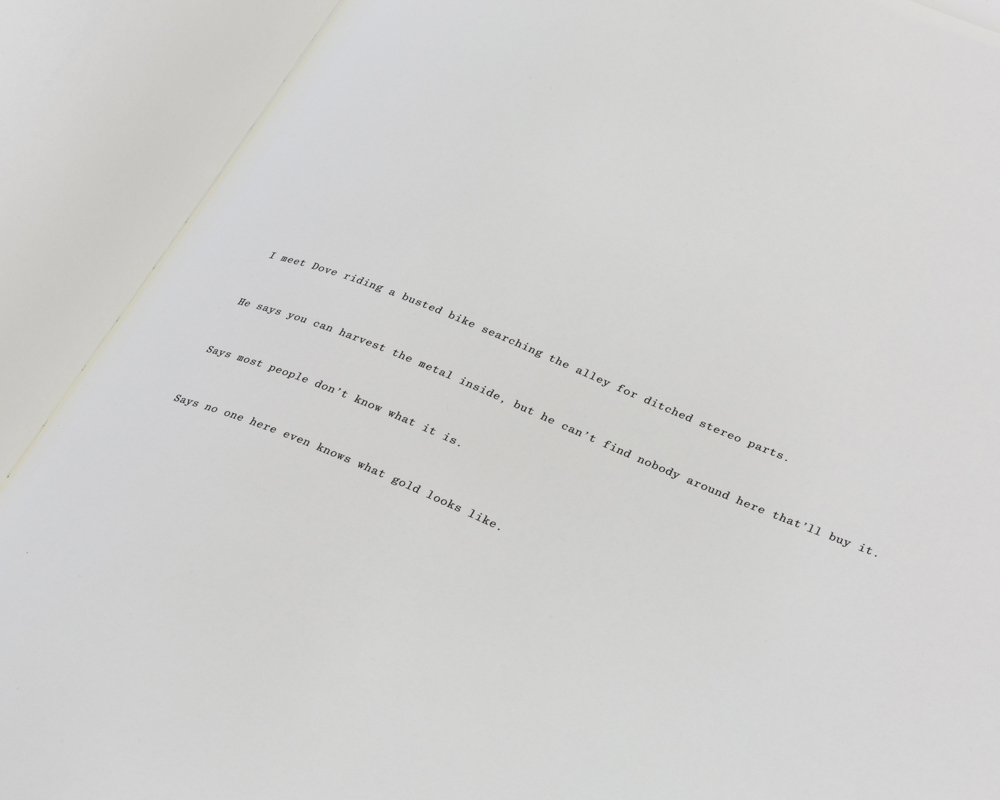

I had been taking pictures for a few weeks when I met Dove. He was rummaging through alleys, looking for old stereos and other gear to strip for metal in exchange for cash. He seemed interesting, so I tagged along for a bit, snapped a few pictures, and we exchanged numbers before going our separate ways. I texted him the next day because I didn’t think I got the pictures I wanted and I never heard back.

A week later, I got a call from an unknown number. It was Dove’s aunt. She told me her estranged nephew had laid down on some tracks outside of El Paso and taken his own life—and that I was the last person he had been in touch with. She thought I should know.

I remember I had recorded a little bit of our conversation when we were chatting and I transcribed that and some other memories and put them aside. I had no intention of putting them in the book. After the pictures were all made and I was sort of reckoning with the entire project and sequencing things is when I made the decision to put them in. They added something to the work that really expanded the portraits and the place in a really lovely way, so I just went with it.

TLC: It’s really a tragic underpinning to this work, untimely death and the weight of even the briefest encounters. I love how the text weaves back and forth between your recollections and Dove’s… the voice noticeably changes but there is still this conflation of narrators. It reminds me that art can be like a collective fiction made in the world but mirroring some sort of truth about ourselves.

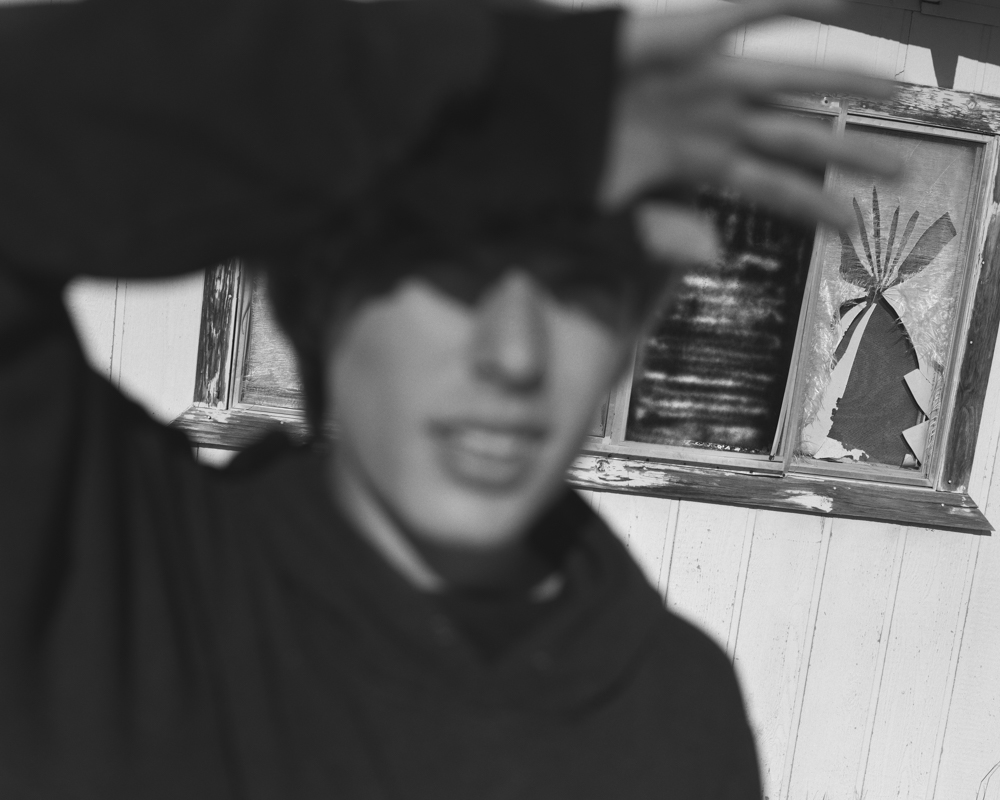

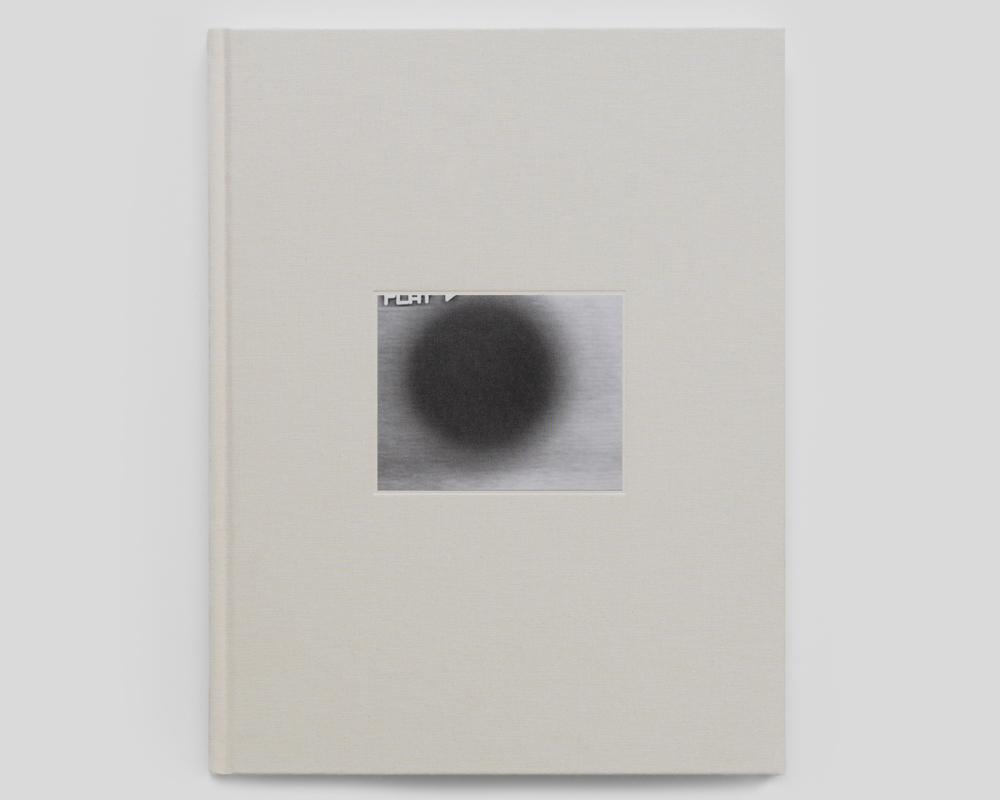

Midway through the book, there is a large spread predominantly black and abstract. This image is so nondescript and yet so immersive. I feel like I’m going to fall into the black hole that Dove spoke of. It pushes the line set with other pictures that have a looseness to them; askew horizons, faces out of focus, and just out of frame. How do you feel your technical picture-making has evolved since Jasper?

MG: That’s fantastic. I love that you felt that. That’s at a moment when the sequence begins to intentionally fall apart. The design “rules” that had been established earlier in the book begin to not hold together any longer. When I look back at Jasper, I can tell how rigid I was with the 4×5. In a lot of the pictures, I can tell that I painstakingly lined things up and got exactly what I was after. I’m much more loose now. I move quickly and let error and luck enter into my practice much more.

TLC: It’s so interesting to me how we contend with control as artists. Maybe it’s not until we feel we have mastered the rules that we trust ourselves to throw them away. I think as a viewer we can feel that difference too… we feel the precision in the chaos and the intention behind letting go and maybe that allows ourselves to go along with you.

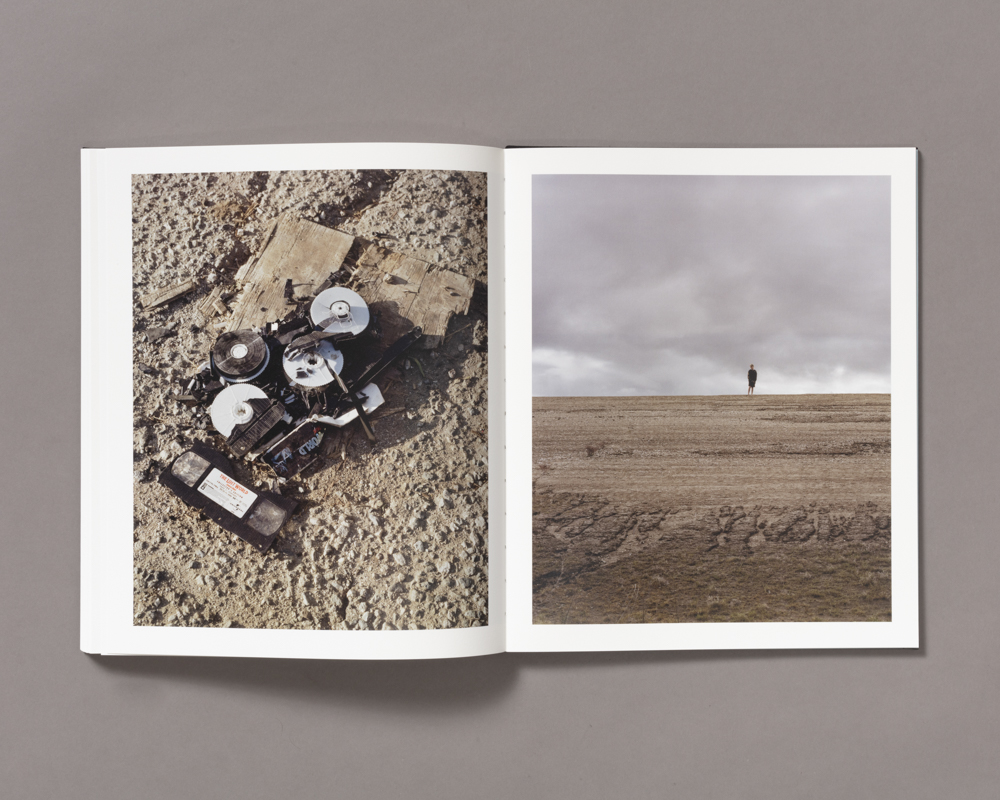

You are also breaking form with the video stills, the artifacting of the footage, the stacks of tapes, its form referencing form. You and I are both of the VHS generation, the punk scene, skate videos, MTV—all subcultures but still a very unifying experience, much different than how I see kids currently, fractured and isolated by social media. Did you feel that shift when working with these kids? Can you talk about how these pictures made their way into the book? You’re photographing the screen while the tape is playing, right?

MG: I originally wanted to include photographs from actual punk shows I was attending in Tucson, but they never quite felt right for the work. Then the pandemic happened, and the shows stopped entirely. A couple of weeks in, my wife and I went to a video store, and I rented a few concert tapes I had watched as a kid. For no particular reason, I started pausing the tapes and photographing the screen. At first, I had no real intention of including them in my work—just a hunch that they might fit. But when I got the first few negatives back and started pairing them with my images, something clicked. It breathed new life into the entire body of work. From there, I started tracking down and rewatching every movie that had shaped me in some way. That eventually led me to feeding my own photographs through the screen and re-photographing them. There are probably dozens and dozens of these screen pictures, but only a handful made it into the book.

Like so many people during COVID, I found myself taking inventory of my past—especially through music. Revisiting the records I grew up with made me reflect on where I came from and how those sounds shaped me. Music was such a defining part of my youth, and in many ways, it still is. The screen pictures became a way to resurrect that past, to weave it into the present, and to bridge my adolescence with the youth of today.

Your book does something similar in my opinion, however you’ve placed your son as the central character in a dreamlike world that is built from memories on the edge of some desert town. When artists create spaces that feel seemingly constructed from memory, I’m always curious how they end up where they end up—can you tell me a little more about how this place came into focus.

TLC: Long live VHS!…I re-watched a lot of old skate films during covid. My kid was now old enough to appreciate them too. He kept talking shit about the messy distortion of the fisheye lenses, but I was so stoked to share them nonetheless. As a teen, making skate videos was my mission in life, it taught me how to be with the world through the use of a camera. It became my tool for connection.

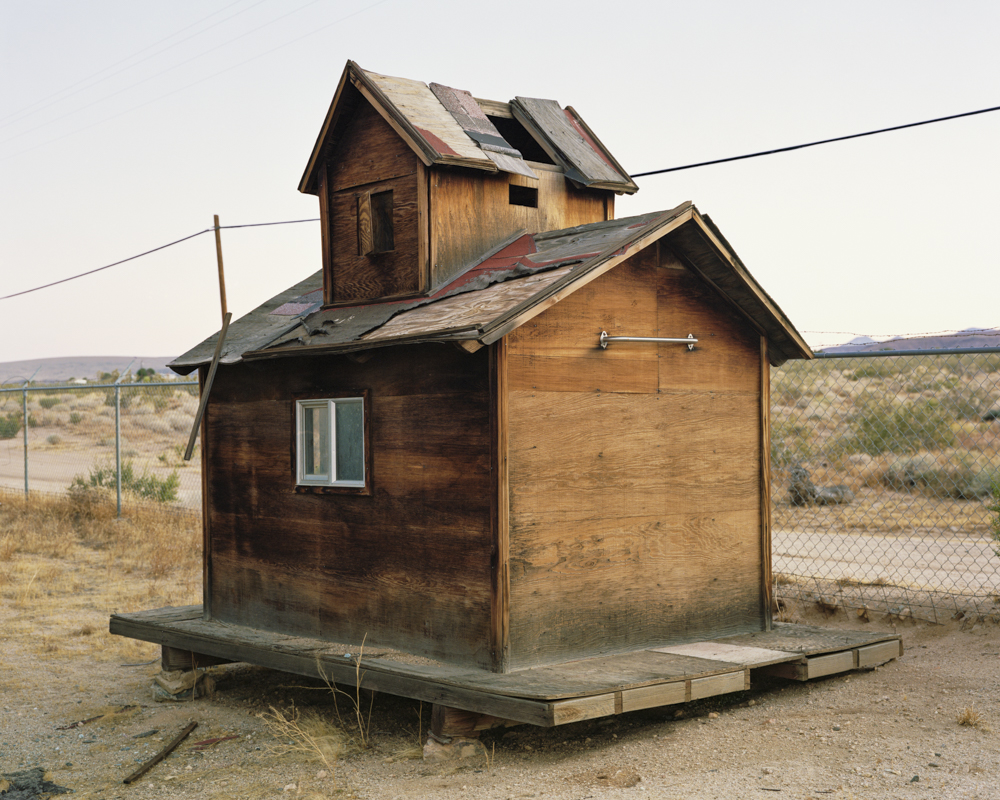

And I totally relate to that sense of taking inventory. All the photographs in A Poor Sort of Memory were made in the desert town where I grew up. After living in NYC for years, I moved back to California and would visit my hometown not with a clear concept to make work there but as this impulse as a mother to reconcile my own upbringing. I had this deep need to understand the terrain of my own childhood—not just the specifics of traumatic events, but the emotional and psychological landscape. What had shaped me? What was I still carrying? How can I face my past to give my kid a better future?

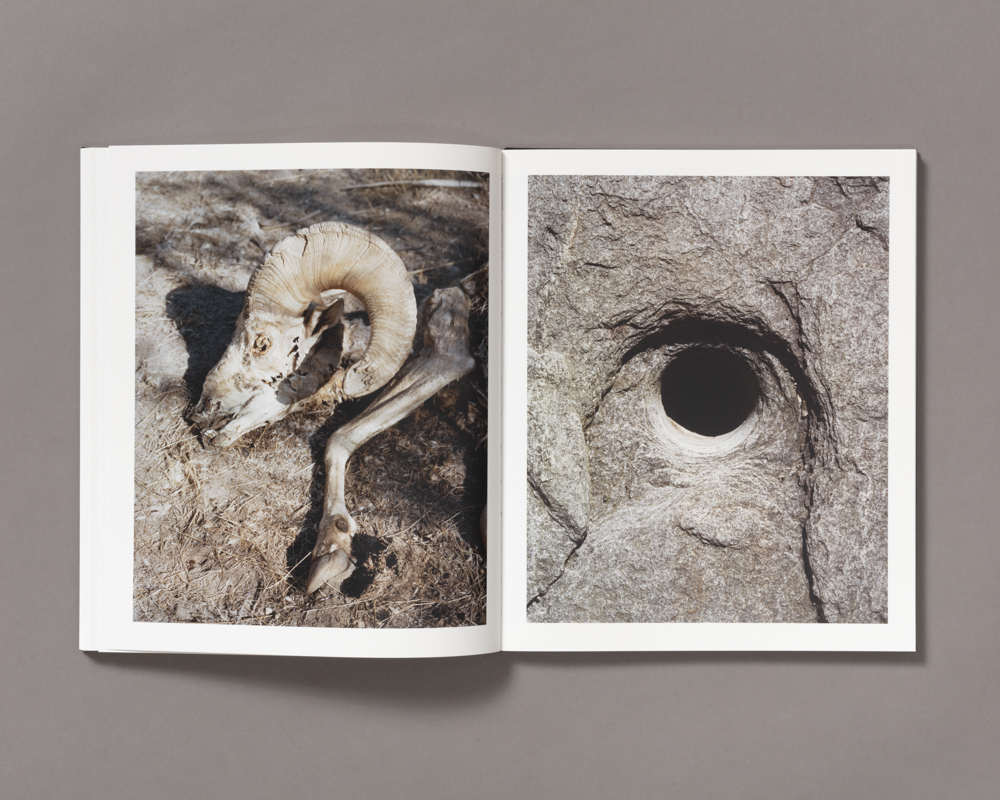

The desert became my collaborator in that process. It’s where I grew up so it was familiar, but I hadn’t truly seen it until I came back with a camera and some distance. The light, the harsh emptiness—it held so much beauty and danger at once. It mirrored the kind of vulnerability I felt back then. Eli became a stand-in for me in many ways, this kid moving through a world that’s both real and surreal, tender and treacherous.

And there’s another layer to all of this—I lost all of my old family photo albums in a structure fire right after we moved. All that skate footage and every image from family history and childhood, gone. I didn’t realize it at the time, but looking back, there must have been an impulse to remake those lost objects for fear of losing the last connections to my past—people, events, and even versions of myself.

So I made lots of pictures. The hard lesson I learned is the more I tried to pin down an old memory into a new photograph, the more the past slipped away and was supplanted with this new experience of creation. So I really had to let go of the agenda of preservation and be with what is. The narrative that emerged—it’s both real and an act of creation. Less of a document and more “based on a true story”…built from what’s remembered, what’s lost, and what’s been reimagined. A portal, really.

MG: I miss the days of renting videos. I get overwhelmed with having everything at our fingertips now. Choice is usually seen as a good thing, but now it’s just too much and it’s debilitating.

I can’t imagine that loss of family pictures and that’s a powerful realization you came to. I’m always curious how artists move through their pasts with the pictures. I can think of a few photographers in our world who do this–almost a recalibration of sorts. How did seeing the desert with fresh eyes reshape your understanding of your childhood and the stories you had told yourself about it? Can you talk a little more about the land as a collaborator?

TLC: I think the main conclusion I came to is that memory, like photography, is not this fixed objective thing. It is completely subjective and morphs over time. And maybe that is a good thing.

For instance, as I was retracing my steps, I went back to the house I grew up in. I knocked on the door and the new family that lives there let me go inside. Matt, I swear it was exactly the same in every aspect, except that it was half the size! Not even half the size. It was so tiny! I guess this makes sense—I was smaller back then, so relatively speaking. Anyway, this process of revisiting started a paradigm shift for me that kept unraveling the “truths” of my recollections with new facts as I experienced them now from my adult vantage point. Everything is always changing. I am always changing. And maybe the beauty is that it leaves room for evolution, maybe I can change the outlook on my past and myself in the process and not be stuck in old story lines.

The way this played out in my photographic process was I became much more open. As I would revisit sites of specific memory, instead of trying to photograph that specific place or object, I would use the psychic energy of the memory to make new pictures, staying open to whatever I saw there. I would let this old place show me new things. And once I made that shift my picture-making really flowed. I saw “pictures” everywhere—there were so many synchronicities, I just had to follow the signs.

This is where the “desert as collaborator” comes in… As I was out seeing with this more open awareness, instead of seeing just the objects and surfaces of the landscape, I saw metaphor and symbols. Concrete washes became roads to travel and doorways became portals to transcendence. It was all of my own psychological projection but I needed the world, this specific world with all its charge from my personal history, to reflect back to me what was going on inside. It all sounds woo-woo, I know, but it really was magical at times.

MG: I totally get that. You sort of stop looking for the world and it sort of just finds you. I love the idea that our memories are malleable and sometimes the memory is actually more special than the actual thing. I have dozens of pictures and paintings that are etched into the back of my brain and there in a way better than the actual pieces themselves.

Did this shift—from capturing specific places tied to memory to embracing openness and symbolism—change your relationship with both photography and your past?

TLC: Yes, for both. The shift was from preservation to creation. Instead of relating to photographs as devices that safekeep the legacy of a loved one or the recollection of an event, I now see them as perishable objects that are only the tiniest slice of a full lived moment. Furthermore, the camera can be a tool for connection and for creating something new. The same shift goes for memory—the stress of trying to hold on to some version of my past was shutting down my ability to be present, with both myself and with my son. Embracing what is here right now frees up the burden to keep the past alive. With both photography and memory, the essence of the past is not lost, it just integrates and evolves.

MG: Has this shift made its way into your everyday world?

TLC: 100%. Without a doubt. If change is the only constant then this evolved perspective brings me more in alignment with both my art-making and the goings-on within my everyday life. There is no separation for me, really. Photography, memory, making, and being… they are all life and I’m living it.

Matthew Genitempo is a photographer and publisher living and working in Texas. He earned his MFA from the University of Hartford. Matthew has released three monographs, Jasper (Twin Palms 2018), Mother of Dogs (Trespasser 2022), and Dogbreath (Trespasser 2024).

Follow Matthew Genitempo on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA. Her monograph A POOR SORT OF MEMORY is now available from Deadbeat Club.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025