Mona Bozorgi: Threads of Freedom

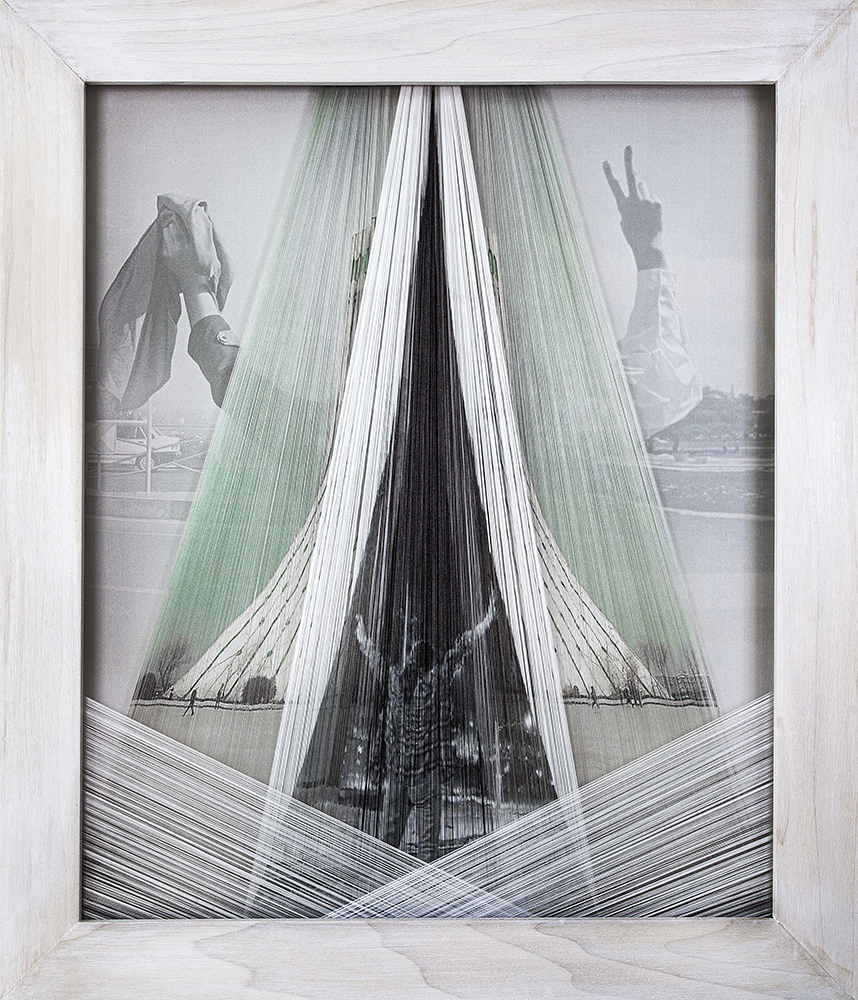

© Mona Bozorgi, Non-Lethal, from Threads of Freedom series, 2024, Archival inkjet print on silk (dismantled), 23 x 23 in.

In the spring of 2024, while exploring Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 50, I

discovered Mona Bozorgi’s series, Threads of Freedom. The work immediately captured my attention, with it’s striking layered visual and conceptual complexity. Engaging with themes of identity, representation, paired with a distinctive approach to materiality,

Bozorgi’s installation amplifies of the voices of Iranian women who have courageously defied systems of oppression by publicly revealing their faces and bodies, both in physical protest and through social media. In this work, the artist recognizes the power of these self-portraits as a form of resistance but also honors the strength of these women in disseminating their own images. By printing these portraits on silk, Bozorgi both symbolically and materially weaves a new visual narrative that challenges and begins to unravel traditional cultural perceptions.

An interview with the artist follows.

© Mona Bozorgi, Unwound, from Threads of Freedom series, 2023, Archival inkjet print on silk fabric, 19 x 38 in.

Mona Bozorgi is an artist-scholar whose interdisciplinary research and artistic practice explore the correlation between representation and performativity in photography. Her research is intertwined with posthuman critical theory and focuses on the process of the materialization of bodies and its impact on the construction and production of identities. Bozorgi’s recent work blends photography, textiles, and installation and explores the entanglement between the materiality of photographs and their meanings. Her work has been exhibited in numerous museums and galleries in the U.S. and internationally. In 2024, she was featured in the Florida Prize for Contemporary Art Exhibition, selected as a Critical Mass Top 50, and was a recipient of the Houston Center for Photography Fellowship. Bozorgi is an Assistant Professor of Photography and the head of the Photography and Moving Image area in the Department of Art at Florida State University.

Instagram: @monbozorgi

© Mona Bozorgi, Amaranthine, from Threads of Freedom series, 2023, Archival inkjet print on silk fabric, 27 x 39 in.

Threads of Freedom

Threads of Freedom intertwines materials and narratives in photography to question traditional representations of women in Iran. This project shares stories of Iranian women using the photographs they have taken of themselves during the recent uprising and protests in the country. At the time, photographers were prohibited from documenting the uprising, and many who tried to take photographs were arrested. So, selfies became a way to document and resist. Women photographed themselves while removing and/or burning their headscarves in public to show defiance and to reclaim the spaces that had been stolen from them for almost half a century.

I conceived this project and its process as a form of protest, a way to resonate with the struggle. Residing outside my country and unable to participate in protests, I found myself overwhelmed and empowered by the images of young, brave women. I collected and printed their images on silk and dismantled the fabric by removing individual threads by hand. Then, I layered the images to create new compositions and to reveal and connect the stories embedded in each photograph. Throughout history, fabric was utilized to simultaneously conceal, beautify, and objectify women’s bodies. In Iran, women’s bodies and hair have been veiled with fabric for centuries. In Threads of Freedom, fabric becomes a surface that reveals women’s bodies instead of covering them, and the threads of the fabric reweave their shared stories. The work acknowledges that the people’s history will remain despite the state’s attempts to censor or erase it.

© Mona Bozorgi, Wreath: Petal 1 of 8, from Threads of Freedom series, 2024, Archival inkjet print on silk fabric, 27 x 42 in.

GB: Tell us a little bit about your childhood and how you became an artist?

MB: I was born in Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution and grew up during the Iran-Iraq War in the 80s. I remember hearing sirens, hiding in bomb shelters at school, and experiencing conflict and political tension, even between members of my own family. Amidst all the turmoil, though, my childhood was filled with adventures, experimentation, nature, travels, sports, making, and reading. I can’t say I had a talent for art from the beginning, but I lived in my imagination and was constantly building things with my hands, and was always doing things in my own way. When I was in first grade, my mom came to school to find out why I did not receive full points in my painting course. The teacher informed her that, instead of painting a fish as instructed, I’d painted a landscape. That was my first introduction to art education! Despite that experience, I later decided to attend art school. I was a first-generation college student, and my parents wanted me to become a medical doctor, not an artist. It was quite a challenge to convince them, but another personality trait I possess is determination. They eventually agreed. As I was deciding which medium to pursue, I had a life-changing realization. While watching a soccer game at home with my family, a game I would not be able to attend as a woman, I realized that if I were a photographer, I’d be able to sidestep the ban and see a game in person. I saw photography as a medium that had the power to represent and to give me entry into experiences that could change my situation. Later, I chose to pursue fine art as a means of using photography to highlight women’s issues and give a platform to those without one. Through my art, I confront historical exclusions based on gender and provide alternative ways of understanding the contemporary self, the fluidity of identity, and the representation of women in underrepresented communities.

© Mona Bozorgi, Wreath: Petal 5 of 8, from Threads of Freedom series, 2024, Archival inkjet print on silk fabric, 27 x 42 in.

GB: Could you discuss the evolution from traditional photographic practices to a more interdisciplinary approach that incorporates objects, textiles, and installation-based elements?

MB: My father bought me my first camera when I was 7, a Lubitel Twin Lens that used 120 Medium Format film. I wasted many rolls of film until I got to the point of learning how to work with the aperture, shutter speed, and ISO. Since I began with film, I was always aware of the importance of materiality in photographic processes. As a young adult, I adopted digital photography and became immersed in social media, but still cherished the tactility of photographs. I was enamored with the affective power of photographs, both their aesthetic power and circulation. Since a photograph was never about “capturing” an image for me, I was always interested in the interconnectedness of image and material. For example, as an undergraduate, I staged photographs, printed in the darkroom, and then painted on the image.

I view myself as an image-based artist; photographs are both my materials and the subject of my work, whether taken by myself or others. The material history of photographs is interwoven with other material histories. I love exploring these material relationships, and they have guided and continue to guide my artistic development. Printing photographs on different surfaces allows for the relationship between the image and material printed upon to express itself in a new, more evident way. Images entangled with handmade papers, fabric, wood, and other unconventional materials, engage senses beyond the visible; they can be touched by a hand or the movement of the air. The vulnerability of images, their susceptibility to being affected, also comes into awareness in these encounters. They move us and are moved by us. I see installation as a way of welcoming the viewer to experience the sensorium and recognize the interconnectedness of the body with the material and meaning of the work.

© Mona Bozorgi, Wreath: Petal 2 of 8, from Threads of Freedom series, 2024, Archival inkjet print on silk fabric, 27 x 42 in.

GB: Talk about the sociopolitical conditions and systemic constraints on women in Iran that are the catalyst for your series, the Threads of Freedom?

MB: In each era of Iranian history, the intricate intertwining of culture and politics constructed an ideal representation and identity that women were expected to adhere to. Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the Islamic State has enforced policies for women’s appearance in society compelling women to follow a mandatory dress code. Growing up under these conditions, I became deeply interested in the performative nature of identities, particularly how women’s identities are constructed and produced. In September 2022, Mahsa Amini, a young Iranian woman who was visiting Tehran with her family, was arrested by the morality police for the crime of not wearing her headscarf properly. Mahsa was separated from her family in the street and was taken to a detention center, where she went into a coma and later died in the hospital. After this incident, people, particularly women, came to the streets, removing and brandishing their headscarves and burning them, or cutting their hair. These acts of protest did not end in the street; women continued practicing civil resistance in virtual spaces by sharing photographs of themselves. These actions were their attempt to free their bodies from an oppressive representational system, crimes violating the country’s compulsory dress codes. While women are/were aware of the danger inherent in sharing their images and the risk of being arrested, in the first few months after the incident, they regularly shared photos as a political act, resulting in a proliferation of images of brave women across social media.

At the time, I was writing a doctoral dissertation on selfies, so I was closely observing how people take photographs of themselves and how bodies and images are entangled with technologies. It was a revolutionary moment that revealed the revolutionary potential of a self-image. The selfies these women took were a form of political action that mark an important moment in the history of women’s representation in Iran. Iranian women, more than ever, recognize the significance of who is photographing them and how they want to be seen.

© Mona Bozorgi, Wreath: Petal 4 of 8, from Threads of Freedom series, 2024, Archival inkjet print on silk fabric, 27 x 42 in.

GB: How did social media play a role in the series?

MB: The governmental control over women’s bodies was not limited to their appearances in public; throughout history, images of women have been intensely scrutinized and regulated. For the majority of Iranian women without any state-sanctioned forum for self-representation, social media not only offers a step toward reclaiming their images but is also a place to share their protests against discriminatory laws. For many of us, taking and sharing selfies is a way to expand our representations beyond what is possible in state media, an act not without risk. Social media has become a platform for resistance. When I saw the proliferation of images of brave women on social media during the Women, Life, Freedom movement, I experienced them as an explosion of the power inherent to social media and self-representation. Women shared incredible images of resistance and defiance, photographs of their injuries resulting from attacks by the police and X-ray images showing ammunition lodged in their flesh. Many women shared selfies of themselves in a cemetery with the photographs of deceased family and friends who had been killed by the state. They echoed the resistance of their loved ones by sharing these photographs on social media, highlighting the violence of the state against nonviolent protestors.

© Mona Bozorgi, Wreath Installation, from Threads of Freedom series, 2024, Archival inkjet print on silk (dismantled), 83 x 83 in.

GB: Discuss the significance of fabric as a medium in the series and the role it plays in conveying the work’s message.

MB: My concept, material, and process all inform one another. In Threads of Freedom, I printed photographs on silk and carefully separated the threads to dismantle the fabric to both reveal and cover bodies and spaces, and to redefine traditional entanglements between women, fabric, and representation. The choice of material allows the works to simultaneously unweave and reweave stories of Iranian women.

As I mentioned, the history of the materials printed upon contributes to the meaning of the images. Throughout history, women have had a complex relationship with making and consuming fabric. Women were involved in fabric making, particularly spinning fiber, a domestic activity considered feminized and women’s work, regardless of whether it was done by men or women. The complex history of textile production is full of paradoxes that tell stories of civilization, hierarchy, control, and labor. The process of removing threads one at a time by hand in my work is connected to the tradition of spinning threads and a reference to “women’s work”. Fabric is utilized to simultaneously conceal, beautify, and objectify women’s bodies. In Iran, fabric is used to cover women’s bodies and hair, veiling them. Fabric in this project does not cover women’s hair or bodies; instead, it becomes a surface that reveals their bodies, and the threads of those fabrics reweave their shared stories. Seeing the threads elucidates the intra-action between material and images of women, allowing the viewer to simultaneously see both.

© Mona Bozorgi, Fruits of Defiance: Shoulder, Eyes, Liver, from Threads of Freedom series, 2024, Archival inkjet print on silk (dismantled), 25 x 80 in x 3.

GB: Reflect on your aspirations for the series. Do you view the work primarily as a form of protest, a means of commemorating the protesters, or perhaps both?

MB: Perhaps both. In the Threads of Freedom series, I view the process of creating the work as an important conceptual element. I view the meticulous process of removing threads from the weft of the fabric as a form of protest and penance, a way to resonate with the pain and struggle of being away from my country in a time when my people fight for their lives and freedom in the streets. As an artist in Iran, I worked in an environment where some degree of self-censorship was required to survive. I learned to express resistance and resilience not only through how my work was presented, but also through the creative process itself. The collective struggle we all carry is sometimes expressed through an artist’s hands and body.

I view myself as a facilitator working alongside others in an ongoing process of creative resistance. The work aims to amplify the messages of Iranian women and to participate in weaving their collective stories together. The work exists as a means of exploring how the affective power of photographs influences social, political, and cultural evolutions.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026