Overshoot #5 – Alex Turner’s “Blind Forest”

Screenshot of Marshall Contemporary’s website announcing Alex Turner’s solo show Blind Forest. On view until August 23, 2025.

Screenshot of Marshall Contemporary’s website announcing Alex Turner’s solo show Blind Forest. On view until August 23, 2025.

©Alex Turner, Burned Joshua Tree with Dried Invasive Grasses, Estimated 100 Years Old, Dome Fire Site, San Bernardino County, CA, 2024. Silver Gelatin Print, 8 x 20 in.

©Alex Turner, Coast Live Oak, Infected with Goldspotted Oak Borer, Estimated 200 Years Old, Ventura County, CA, 2025. Silver Gelatin Print, 8 x 20 in.

Yogan Muller: Alex, we’re getting together on the occasion of your solo show, Blind Forest, at Marshall Contemporary in Santa Monica. Blind Forest is a tender, heartfelt, and simultaneously serious inquiry into how trees absorb and reflect human and environmental histories. There are many layers I want to unpack, but first, I feel it’s important to know about your background working with ecologists and the tree people in California.

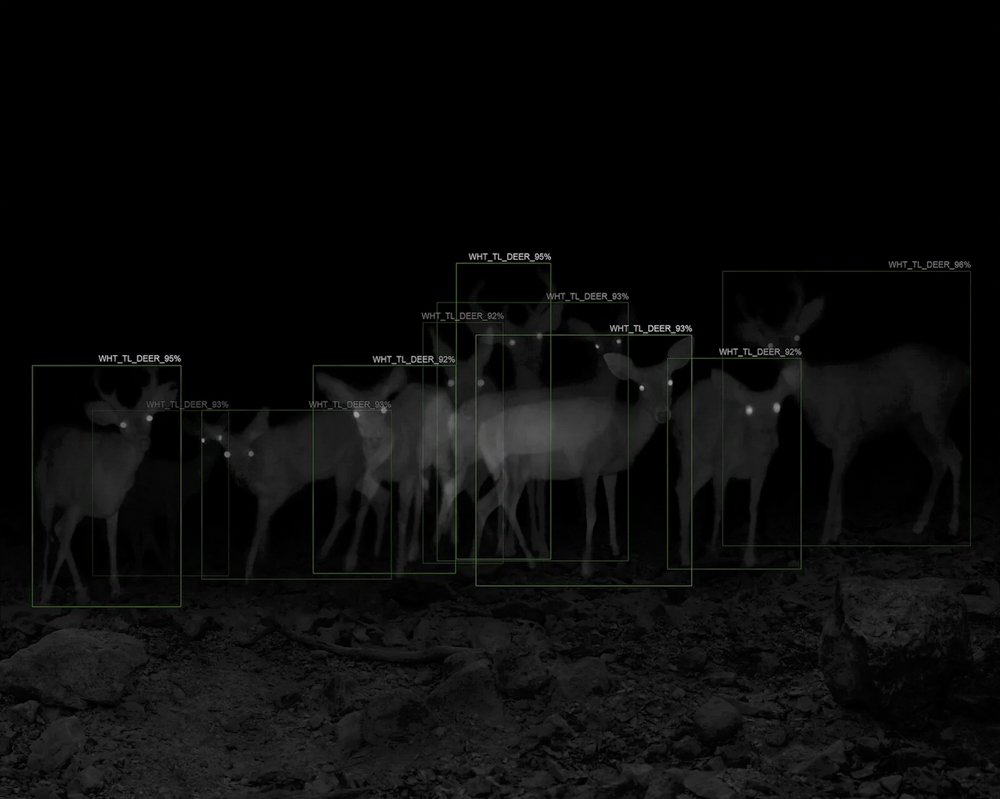

Alex Turner: This is my follow-up to Blind River, a project I did about five years ago. That was a project where I had worked with wildlife biologists at the University of Arizona, who were using remote sensing technology and AI recognition software to track and identify jaguars and other apex predators that were crossing the US-Mexico border. It ended up being a project that had a lot of different facets and angles to it, and pulled out a lot of different concepts and themes. I’ve always been interested in ecological issues overlapping with sociopolitical issues in contested spaces, and the technologies we use to understand them.

©Alex Turner, 8 Captures of 2 Coyotes, 2-Hour Interval, Abandoned Endless Chain Mine, Patagonia Mountains, AZ, 2019

©Alex Turner, 10 Captures of White-Tailed Deer with A.I. Recognition, 1-Week Interval, Patagonia Mountains, AZ, 2019

That project utilized existing infrared technology and AI software to extract data and then parse it out and organize it in different ways. I was always interested in the detachment that comes with remote sensing: how you’re only fully immersed in this space based on the data you’re collecting, but you’re also completely removed from it because all of this footage and activity is being captured without you being present.

Blind River went out into the world after I graduated and moved to Los Angeles and began working at an environmental non-profit focused on large-scale ecological restoration projects. We did a lot of reforestation projects in the mountains surrounding L.A. For us, the team that I worked with, that involved planting tens of thousands of native oak and conifer species to repopulate and restore burned areas and degraded ecosystems. While I worked with this team, I developed a whole new respect for trees, not just as ecological keystones, but also as cultural keystones. And it got me thinking a lot about how we, as humans, have manipulated and shaped forest ecosystems just as they have, in turn, manipulated and shaped us.

As I’m spending time out in the field planting these trees and learning the history of these damaged spaces and the importance of healthy trees there, I start imagining a follow-up project that takes some of the ideas and concepts and themes from Blind River, but brings it not only to California, but maybe steers the lens more towards an ecocentric conversation as opposed to a human-centric conversation. Blind River was very much how humans are surveilling, identifying, and extracting data from these spaces. Human subjects within these spaces were very much at the forefront of that work. For Blind Forest, I was very much interested in trees being at the forefront of the work. Humans and other subjects are almost secondary – if they’re present at all, they’re responding to the trees.

©Alex Turner, Burned Mexican Fan and Queen Palms, Palisades Fire Scar, Estimated 70 Years Old, Los Angeles County, CA, 2025. Silver Gelatin Print, 14 x 35 in.

Yogan Muller: Your solo show, which is on view until August 23rd, 2025, consists of 16 works, all gelatin silver prints. However, the viewer quickly realizes that your impeccable black and white images reveal portions of the physical world we cannot see. You used another thermal camera to capture radiating infrared energy, obtaining vital insights into tree health and life. Tell us just more about your photographic process and what drove you to go deep into this remote region of the light spectrum.

Alex Turner: Thermal imaging is really popular in the environmental sciences and among arborists to determine the health of trees. Thermal imaging is heat-based imaging. In my images, the more an object emits heat, the darker that aspect of the photo or image is going to be. As a botanist, arborist, or restoration ecologist, you can study how healthy or unhealthy a tree is based on how much heat is emitted from the bark, branches, or even leaves.

©Alex Turner, Arroyo Willow and Fern Grove, Monterey County, CA, 2025. Silver Gelatin Print, 14x 35 in.

I realized that it was this very uncanny, unique way of looking at a tree. Depending on the way you set up the camera, the result almost looked and felt like a black and white photograph. You mentioned that these are silver gelatin prints. I spent a lot of time trying to determine exactly how I wanted to exhibit Blind Forest, and I kept coming back to silver gelatin in part because some of the photos ended up looking almost like traditional black and white film photographs from a different era. There was almost like a romanticism to it, something I didn’t expect until I started assembling these images. Thinking of trees as these historical objects, I like the idea of referring to a more historic or past medium or version of photography, and having a conversation with past landscape photographers using the silver gelatin.

I think working in restoration ecology and developing this project, I became aware of this concept called cathedral thinking, which is essentially long-term thinking and directly refers to the history of building cathedrals. These buildings can take several generations to construct. The builders and architects will not see it through to fruition, but they’re part of this community that’s building something greater than themselves. A lot of the work that we did involved planting trees that will last two, three, four hundred years, hopefully. They’re going to far outlive us. And a lot of the forest that we’re working in had ancient trees that were much older than us. That allowed me to view history a lot differently. With trees, and the histories they record, we’re able to look into the past much more than we can within our own lifespans. And as a result, you’re able to understand the current state of our environment based on how this tree lived a century ago versus how it’s adapting today. And you’re able to project into the future with more precision and clarity, too. It’s giving you this opportunity to transcend generations and build a narrative and an understanding of our surroundings in a way that you can’t otherwise do.

Yogan Muller: You almost take the pulse of tree life. What compelled you to do this initially?

Alex Turner: When I first started studying these trees with the thermal camera, I was struck to see life and decay depicted this way. You see the energy emitting or being radiated from these trees. Sometimes, you’re also watching a tree die in front of you. It had a stronger impact looking at it this way because a lot of times you don’t necessarily see it with your naked eyes that a tree is dying, but it could be emitting less heat, so it’s reading cooler in thermal infrared. And I felt like there was more of an emotional impact to it than you would get from a regular photograph. I wanted to explore this hidden aspect of nature that our eyes are not privy to. Kind of the same way that I explored that with Blind River. You know, what happens in these spaces when we’re not there? What’s happening in these tree-populated spaces all around us? There’s a current, there’s a system that is at work all around us that we’re not able to tap into. For me, thermal imaging allowed for a very haunting, enigmatic way of viewing these systems.

Yogan Muller: It seems to me there’s a long tradition of photographing trees, which is reflected in your show through the inclusion of historical photos. Visitors get to see pictures from the late 19th century, a time when photography was used to capture a nascent and yet already clear dominion over the natural world, with industrial logging machines, for example. Human scales started to collide with natural scales. I wonder what kind of perspective you feel you created with these historical photos.

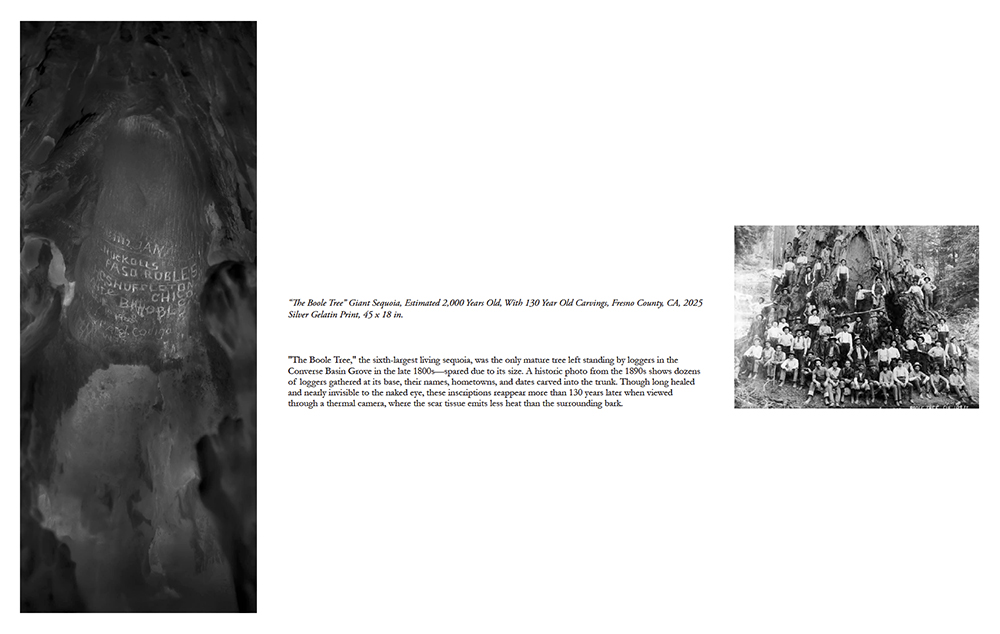

Alex Turner: I wanted to have a conversation with history and so in a lot of instances, the context that surrounds each tree was important. A lot of the trees I’ve photographed had a very specific story to them. For me, juxtaposing some of the images was really important.

©Alex Turner’s “Blind Forest,” installation views at Marshall Contemporary, CA, July 2025. Historical pictures are reproduced alongside Turner’s large gelatin silver prints.

Sample page of Alex Turner’s research document and image catalog for Blind Forest. 2025.

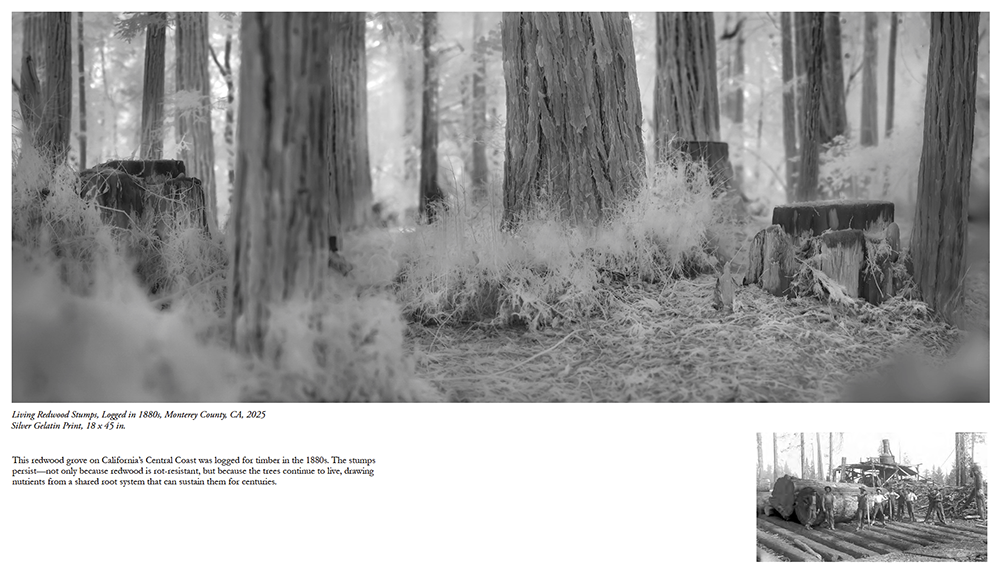

For example, the piece titled Clementines, Felled Due to Drought, Estimated 40 Years Old, Kern County, CA, 2025, this was an orchard that was felled a few years ago due to drought. I included an image from the early 19th century, when citrus was first introduced to California, that showcased an endless abundance of fruit. I wanted to show this, specifically in California, because of how much we relied on the productivity of natural resources without a certain level of responsibility. And now, in 2025, we’re kind of dealing with the repercussions of that lack of responsibility. I also allude to that in the pictures of redwoods and sequoias being logged. In hindsight, it’s crazy to think that they were once considered nothing more than a resource. And, in a lot of instances, that’s still the case…it’s just as topical today, now that a lot of national forests are being reopened for logging. That’s a whole separate conversation, but I felt like showing these two different depictions using different imaging technologies allowed us to see the different narratives, the different ways that these trees have been treated and the preciousness of trying to preserve them, and the importance of that.

Yogan Muller: So, enriching our perception with non-visible light can foster deeper bonds with trees and the natural world at large?

Alex Turner: Yes. I think using that technology is highlighting something that is not only emotionally valuable for us but also scientifically valuable. The redwoods, for instance, in that photograph where the trees were logged, the heat being emitted from the stumps is pretty stunning because it showcases that these trees are still living!

©Alex Turner’s research document and picture catalogue. 2025.

Alex Turner, Living Redwood Stumps, Logged in 1880s, Monterey County, CA, 2025 Silver Gelatin Print, 18 x 45 in.

Not only because redwoods are rot-resistant, but also because they have these very deep, complex root systems and mycelium networks that allow neighboring redwoods to maintain the health and survival of felled trees.

With the sequoias, the image where I have the carvings from the late 1800s, when loggers chose not to fell that one tree but instead engraved their names in it. That mark is still there, although to the naked eye, it’s barely visible. It’s mostly healed over now, but the scar tissue does not emit the same amount of heat. Thermal infrared allows us to essentially remember this moment in history in a way that our eyes don’t.

Yogan Muller: What transpires in your show is a giving of honor to trees. And there’s a picture that seems to directly address this. There’s a large crowd of people standing in front of the General Sherman, a 2,000-year-old Sequoia, considered to be the largest living tree on Earth by volume. In the center of the frame, there’s a figure that has a slight tilt of the head. I read it as a moment of awe in front of forces and lifespans that far transcend human scales and preoccupations.

Alex Turner, “General Sherman” Giant Sequoia, Estimated 2,200 – 2,700 Years Old, Tulare County, CA, 2025. Silver Gelatin Print, 14 x 35 in.

Alex Turner: I like it that that one is speaking to you. There’s a certain spectacle. Here this age-old sequoia is celebrated. But I like the idea of showing both the pros and negatives of spectacle. There is another sequoia image in the show, where the viewer sees these magnificent living objects being treated as both a resource – or a form of profit – versus today, where Sequoias are incredibly charismatic objects and held with a lot of respect. Let’s not forget people come from all over the world to see this tree. However, a couple images down from that, there’s the Hangman’s Tree… There are many trees around the United States and elsewhere that have these deeply negative historical connotations that are also treated as spectacle. We love to project symbolism and meaning onto trees, either fairly or unfairly.

Also, the idea that a tree, which is indifferent to humans, could absorb all of that meaning, how it becomes a mirror of our intentions, how it can be celebrated or vilified, is fascinating to me. In the natural world, they’re all held in similar weight and importance to their ecosystems.

Alex Turner, Coyote and Clonal Quaking Aspen Grove, Estimated 1500 Years Old, Mono County, CA, 2024. Silver Gelatin Print, 14 x 35 in.

Alex Turner, Coyote and Clonal Quaking Aspen Grove, Estimated 1500 Years Old, Mono County, CA, 2024. Silver Gelatin Print, 14 x 35 in.

Yogan Muller: What did you learn while photographing trees this way for so long?

Alex Turner: Once the work went up on the walls, I started hearing some people saying, “Oh, this is my favorite picture by far.” The sheer variety of responses I got from people relating to certain images or being drawn to or not drawn to other ones was fascinating. It showcases the diversity with which we as humans are attracted to trees and how we assign importance or value to trees. I’m encouraged by that level of enthusiasm and the variety of personal connection that I’ve received.

Installation views of Turner’s Blind Forest at Marshall Contemporary, Santa Monica, CA. On view until August 23, 2025. Photos courtesy of Thomas Blank.

That was apparent even during the making of this work. I was stopped a lot by people as I made the pictures, and they would be like, “Oh, I’m so glad you’re photographing this tree.” And they would go on: “I’ve walked by this tree every day for years and it’s always held a special place in my heart.” Other people looking at the work later said: “I had no idea that this tree existed. I need to go find it. I need to go see it.” I think there’s a lot of passion and interest in trees. I’m still not entirely sure why humans are so attracted to these incredibly large sentient organisms. I mean, myself included, I’m completely obsessed with them. I couldn’t tell you exactly what it is about their presence that I’m obsessed with, but I’ve been encouraged by just how much we care for and love these trees in general, despite all the challenges that they’re facing and despite a history of exploiting them. On the other hand, there are a lot of people who have devoted their lives to trying to save trees. Their ability to profoundly impact all of us, I think, is important to acknowledge.

Yogan Muller: Alex, what does photographing in a warming world mean to you?

Alex Turner: I’m glad that I see so much environmental art being made or art that’s showcasing the natural world and paying respect to it. I think especially in a warming world, it’s easy to get caught up in elegy and focus on either the loss we’ve experienced or the impending losses that we will experience. In Blind Forest, there is some of that loss…it certainly plays a role. But I also think it creates a much more complex conversation centered on hope and resilience. At least I hope that can be taken from the show.

I do believe that ecosystems and the natural world have an incredible ability to fight through and fight back, and persevere. I hope that in a warming world, people can make art that’s not just about the loss as it pertains to the environment. I hope that we continue to see work that plumbs the depths and the ability of nature to persevere through it. I hope people find that in my work, and I hope other artists can make work that inspires people to do the same.

Biosketch: Alex Turner (b. Chicago, Illinois) is a visual artist whose work has been exhibited internationally. He was named to the Silver Eye Center’s inaugural 2021 Silver List and Photolucida’s 2020 Critical Mass Top 50, won First Place in LensCulture’s Black and White Photo Awards, received SPE’s Innovation in Imaging Award has been named a finalist for many other awards and scholarships. His work is held in numerous collections including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Tucson Museum of Art. He has been featured in publications including Patagonia, Adventure Journal, Lenscratch, Fisheye, Der Greif, and C41. He holds an MFA from the University of Arizona and currently lives in Los Angeles, California.

Website: https://www.alexturnerart.com/

Instagram: @alex_turner_art

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Yi Wan Gyo: Nirvana-Beyond DarkJanuary 13th, 2026