Photographers on Photographers: Emily Rena Williams in Conversation with Kristine Potter

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today Emily Rena Williams and Kristine Potter are in dialogue. Thank you to both of the artists.

I first encountered Kristine Potter’s prints in person at The Do Good Fund, a Georgia-based collection of Southern photography. The collection includes four images from her Dark Waters series – Hell For Certain, Disappointment Creek, Deep River (Where Naomi Was Drowned) and Dark Water. Over the last few months, I’ve found myself revisiting the prints along with her books, Manifest and Dark Waters, frequently. She has a unique way of examining the American landscape and the people who occupy it which feels both intimate and unsettling. Her work examines power, gender and place in the tangled intersections of American myth and reality. It asks the viewer to dissect, or at least question, the ideas and stories therein.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Kristine about what drives her work and how it has continued to evolve.

Kristine Potter is an artist whose work explores masculine archetypes, the American landscape, and the cultural tendency to mythologize the past. Her first monograph, Manifest, was published by TBW Books in 2018. She has received numerous national and international awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship (2018), the Grand Prix Image Vevey (2019–2020), and the Hariban Prize (2023). Her second monograph, Dark Waters, was published by Aperture in 2023. Potter’s work is included in numerous public and private collections, such as the High Museum of Art, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, the Georgia Museum of Art, Light Work, the Swiss Camera Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. She is an Assistant Professor of Photography at Middle Tennessee State University and is represented by Sasha Wolf Projects in New York and MiCamera in Milan.

Instagram: @kristine_potter

ERW: Throughout your career, you’ve consistently made a lot of portraits of men, but the conceptual framing has shifted. Can you talk a little bit about the trajectory of your work and how your thinking about masculinity has or hasn’t changed throughout?

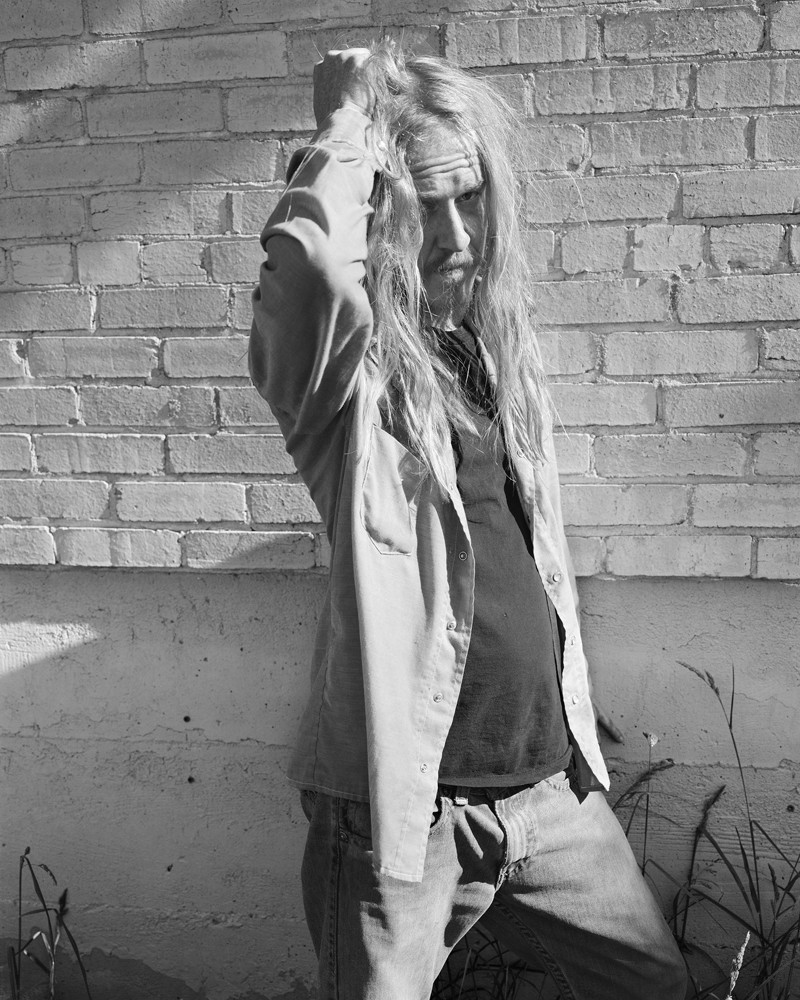

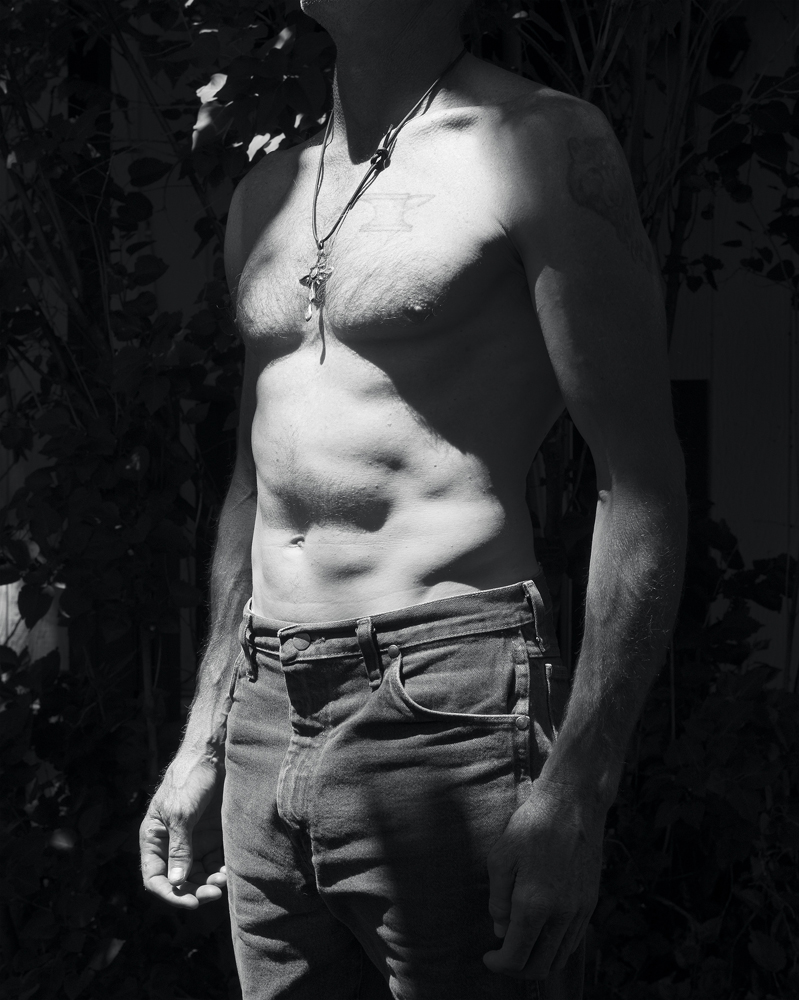

KP:I think what has shifted is my willingness to move from curiosity into critique. In The Gray Line, I was trying to understand a highly codified expression of masculinity, military identity, and how young men make sense of it. There was reverence in that work, or at least a sense of careful attention. Manifest was more confrontational. I was chipping away at a cultural fantasy, the rugged cowboy, and showing the vulnerability underneath. With Dark Waters, I turned the lens more squarely on violence itself. The shift there was also emotional. I was not trying to understand men, I was trying to visualize the psychological cost of living in a world shaped by their dominance, especially for women.

There are other concerns at play too, things tied to the act of photographing that make me want to approach ideas differently. I work on singular projects for so long that once they are complete, I often feel compelled to pivot entirely. From young men to older men, from high-key western light to the darkened forests of the South. And maybe… from looking at men to not looking at them so directly. That’s probably part of it too.

ERW: A lot of your work deals with masculinity and violence, whether directed towards the land, other people, or both. This is a theme you’ve explored for a long time, also heavily influenced by your family background. Dark Waters in particular seems to deal with femininity as well. Can you talk about what continually draws you to exploring masculinity, and why you frame Dark Waters as an exploration of masculinity rather than femininity?

KP: Masculinity is a subject I return to because it is so entangled with power, mythology, and violence, both overt and psychological. I grew up watching these dynamics unfold in real time, not just in my family but in the broader cultural narratives that shaped us. I have always been interested in how these forces get mapped onto people and places. Even when I center women, as I do in Dark Waters, I am drawn to the unseen systems pressing around them, systems often built by men, lingering like a shadow or echo. So while that work gives space to women’s experiences and fears, it is still ultimately about the male psyche and how the threat of male violence lingers in the collective imagination. Dark Waters is not about femininity so much as it is about what happens to women when masculinity goes unchecked.

ERW: The landscape is important in both Manifest and Dark Waters and functions as a character rather than a setting in the work. What draws you to make work about the landscape as it relates to masculinity? How does the landscape itself influence your work? Why is it important to you to portray it in the really specific ways that you are?

KP: I have never been interested in photographing the land as a neutral or decorative backdrop. The American landscape is a charged space, loaded with history, ideology, ambition, and violence. It has been used as a proving ground, especially for men. What interests me is what remains when those myths break down. The terrain in Manifest, for instance, holds the residue of Western masculinity, but the men I photographed there are not heroic. They look weary, suspended in a space where the myth no longer holds. In Dark Waters, the landscape becomes more psychological, at times claustrophobic or unnerving. I wanted the viewer to feel the disorientation of fear in the natural world, as if the land itself holds cultural or historic energies.

ERW: Both the South and the West are regions that have extensive mythology associated with them, which is often influenced by and in turn influences reality. How do you negotiate the relationship between fact and fiction, myth and legend, stereotypes and reality?

KP: I have always been drawn to the spaces where fact and fiction blur. Myths persist because they serve a function, whether emotional, moral, or social, but they also distort or overwrite lived experience. In Dark Waters, I used visual cues like curtains, theatrical lighting, and formal staging to suggest that what the viewer sees may be constructed, even as the emotional undercurrent remains real. I am not documenting crimes. I am examining how violence is mythologized, aestheticized, and consumed through stories and spectacle. The American South is especially saturated with this kind of storytelling, from early murder ballads and Southern Gothic literature to contemporary television and film, and endless streams of true crime podcasts. I wanted the work to dwell in that ambiguity while also unsettling it.

Manifest considers how myth draws certain men to the American West. I was interested in what they thought they would find there, who they thought they could become, and who they are. But I also wanted to destabilize the myth of the landscape itself. Instead of treating it as a stage for national dreams and personal ambition, I tried to present it as I felt it; resistant, indifferent, even inhospitable to human control.

I suppose both projects ask how images shape belief and how belief, in turn, shapes behavior.

ERW: In one of your podcast interviews with Sasha Wolf, you mentioned growing up in a military family in a small town in Georgia, but noted that you weren’t culturally Southern. What drew you back to the South for Dark Waters?

KP: There is a kind of unresolved friction for me when it comes to the South. I never felt like I belonged culturally, but I know it. I have always been haunted by its psychological atmosphere, the storytelling, the repression, the beauty, and the danger. Dark Waters felt like an opportunity to make sense of that tension. It is not a Southern Gothic project exactly, but it shares some of that DNA. I was interested in how narratives, especially violent ones, shape a place and how those stories get lodged in the landscape and in the body.

ERW: Dark Waters was published in 2023. Quite a lot has happened politically since then. Has your relationship to this body of work changed given the rhetoric and action of the current administration and the erosion of women’s rights, particularly in Southern states?

KP: It has definitely shifted. When I was making Dark Waters, I was focused on the slow, atmospheric ways that violence gets absorbed and metabolized, especially through entertainment. I was looking at the emotional residue that accumulates when violence against women becomes narrative background, when it becomes something we expect, even aestheticize. Since the book’s release, though, the cultural climate has grown more openly hostile. The rollback of reproductive rights by the Supreme Court, for example, made certain fears that were once ambient feel immediate and structural.

When I first started making work, the term toxic masculinity was not yet in wide circulation. Now it is part of the broader discourse, and I can see how that language helps clarify some of what I have been circling for years. What has become more alarming is how many people have begun to actively defend or reassert those toxic frameworks. Online spaces like the manosphere have calcified into deeply misogynist echo chambers. They are not fringe anymore. There is a real emboldening happening, and it is bleeding into policy, media, and daily life. In light of that, one possible reading of Dark Waters is as a kind of warning, about how normalized violence can become and how easily cultural narratives slip into political reality. The work may now carry a sharper urgency than it did when I began it.

ERW: I want to shift a little bit to one of the more practical dimensions of your process. Can you talk about the reality of making this work as a female photographer?

KP: I travel alone and I move through environments that are not always welcoming. In Manifest, I was staying in remote areas and approaching men I did not know. That required a kind of alertness. I had to read situations quickly, know how to establish trust, and decide when to walk away. In Dark Waters, I was often alone in the forest. That solitude was essential. I cannot make the kind of work I want to make with others around me. I need to be unobserved in order to fall into a rhythm and work without self-consciousness. There were moments when I felt uneasy, and I started to pay attention to that feeling. Why did I feel unsettled? What did I imagine, and where did that come from? Those questions began to shape the work. I try to stay tuned in to both the atmosphere of a place and what I bring into it. My instincts, my expectations, and my sense of control are all part of the process. The challenge is to remain open while staying aware.

I do not think we talk enough about how the body of the photographer shapes the work. There is a long history of photographic exploration that assumes ease of access and safety. But that is not the reality for everyone. For some of us, moving through the world with a camera means navigating risk, exposure, and a constant awareness of how we are perceived. That vulnerability inevitably influences what gets made, what gets seen, and what gets left alone.

ERW: Any advice for young photographers and photography students?

KP: Do not be afraid to take your time. So much of the current culture encourages speed, fast production, quick understanding, and fast dissemination, but good work often needs to steep. Make pictures that confuse you. Let your curiosity guide the process, not just your ambitions. And read. Look at things outside of photography. The more you can draw from other disciplines, the richer your visual language will be.

ERW: Finally, are there any upcoming exhibitions, publications, or things you’re working on that you’d like to share?

KP: Yes, I have a few upcoming exhibitions, Dark Waters will tour a few museums and institutions over the next few years. I’m also working on a small retrospective to be shown at my undergraduate alma mater, University of Georgia. It’s the first time I’m showing all these bodies of work together and it’s been a rewarding process.

As for new work, I am in the early stages of a project I’m calling The Listening Ground. Like my previous work, it explores the psychological charge of the American landscape, but this time through the lens of female presence and hidden forms of power. Set in the deserts of the Southwest, the project is beginning to follow the traces of women who operate outside dominant systems, often in spiritual or esoteric roles. It is still taking shape, and I am letting the work reveal itself slowly, so don’t hold me to that premise…

Emily Rena Williams is an artist and educator interested in investigating communal and individual memory, identity, and placemaking through photography, writing, and audio. She is currently a curatorial fellow at The Do Good Fund in Columbus, Georgia. Emily holds a BA in fine arts and history from Haverford College, an MFA in photography from Louisiana State University, and is an incoming American Studies PhD student at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her current body of work documents Jewish communities past and present in the rural and small-town Deep South through photography and oral history interviews. She has support from the Southern Jewish Historical Society, Texas Jewish Historical Society, the Alabama Folklife Association, and the Texas State Historical Association.

Instagram: @erwilliamsphoto

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026