Photographers on Photographers: Leni Mae Wiegand in Coversation with Lorenzo Triburgo

Every August we ask the previous Top 25 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners to interview a hero or a mentor, offering an opportunity for conversation and connection. Today we share a conversation between Leni Mae Wiegand and Lorenzo Triburgo. Thank you to both of the artists.

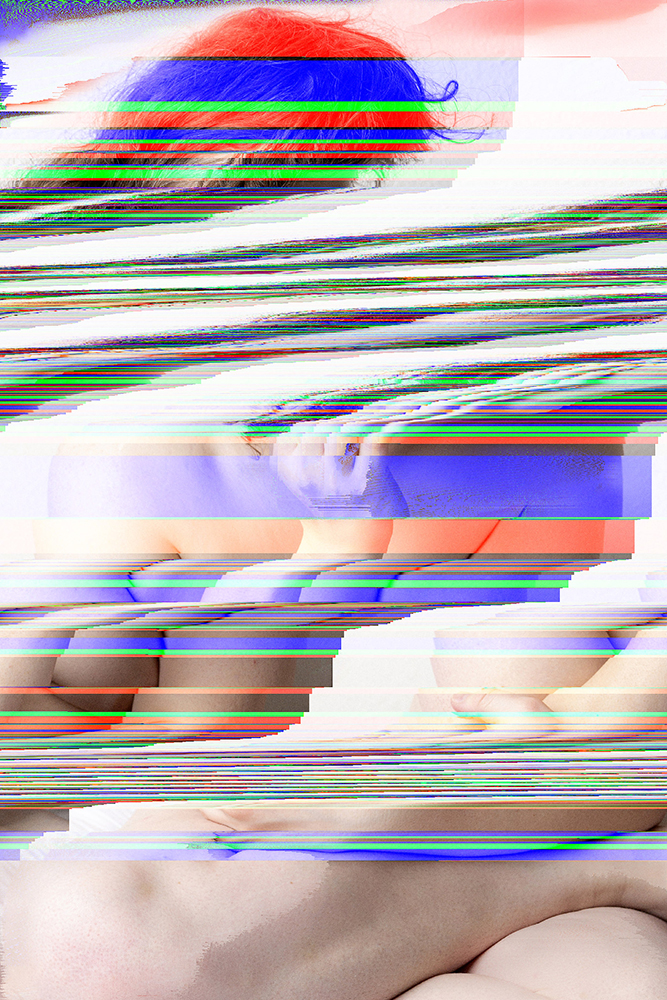

The first time that I ever encountered Lorenzo Triburgo’s work was at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago as part of the “Beyond the Frame” exhibition in the summer of 2022. It was the image Venus, where Lorenzo gracefully and glitteringly embodies the celestial planet, from their collaborative project with Sarah Van Dyck, Shimmer Shimmer. What struck me first as I walked through the gallery was the obvious queerness of the image and then, more specifically, the obvious transness of the image. Gender was being played with, bent, and fully explored as a possible point of political and social disruption within the image, making it stand even against numerous other beautiful images at MoCP.

At this time, I had only recently accepted that I was trans and started hormone therapy just a few weeks prior. I still lacked a good idea of what it meant to be trans, trying to figure it out on my own. All of my understandings of it came from TV, movies, and more recently, social media, which is often aggressively negative, and in ways deeply destructive. So, being in the gallery, seeing what power in embodying transness can look like was extraordinarily moving, and made it start to feel like it was ok to represent myself within my own imagery.

I have been lucky enough to be able to connect with Lorenzo last year, where their kind words, guidance, and mentorship served as a turning point in understanding my own work, helping me understand what I was doing and how I could find strength and comfort in making it. As such, it feels only appropriate to once again sit down with them on my third anniversary of starting hormone therapy (and unfortunately on the same day as the Supreme Court Skrmetti ruling announcement) to discuss queer photo projects, the power of representation, and how art can be a protest.

Lorenzo Triburgo is a performance and lens-based artist, curator, and educator who has hosted workshops, lectured, and exhibited throughout the U.S. and abroad. Often in collaboration with their partner Sarah Van Dyck, PhD, they work to elevate trans*queer subjectivity and abolitionist politics. From painting oversized “Bob Ross, The Joy of Painting,” landscapes as backdrops for Transportraits, to standing in place before the Stonewall Inn for 24 hours, and most recently ceasing to take testosterone after 10 years of transgender “hormone therapy” as a performative attempt to embody gender abolition, their interdisciplinary methods weave personal experiences with political moments and theoretical concerns with calls for action and hope for a liberated future. A Baxter ST/CCNY Resident and Bronx Museum AIM Fellow, permanent collections include the Museum of Contemporary Photography, (Chicago, IL), and Portland Art Museum, (Portland, OR). Select exhibition venues include BGSQD, NYC; SoMad, NYC; Kunst und Kulturhaus, Berne, Switzerland; Dutch Trading Post, Nagasaki, Japan; The Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA; and Oude Kerk, Amsterdam, the Netherlands as the winner of the Pride Photo Award. Select publications include GLQ, Art Journal, the Transgender Studies Reader 2, and Photography: A Queer History.

Lorenzo is a full-time (and fully online) instructor of art, and graduate faculty in women, gender, and sexuality studies at Oregon State University who teaches critical theory, photography, and gender studies with a focus on expanding liberatory learning practices in online environments.

Instagram: @lorenzotriburgo

While she did not participate in the interview, she is a collaborator for a lot of the work discussed.

Sarah Van Dyck is an Industrial-Organization (I/O) psychologist who specializes in mixed methods research, blending and translating quantitive data with qualitative audio, visual, and narrative sources. Her professional interests include gender and identity at work, occupational health psychology and disparities in underrepresented populations, and LGBTQIA research in applied settings. She has conducted research with organizations such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Center on Work-Family Health and Stress, and Keaiser Permanente Center for Health Research. Sarah was the recipient of a NIOSH Occupational Health Psychology Training Fellowship, and she has co-authored research articles in peer-reviewed publications such as the Journal of Business and Psychology and a variety of translational research outlets. She holds a BA in Sociology/Anthropology from Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, and an MA in I/O Psychology from Portland State University, where she is currently an ABD doctoral candidate in Applied Psychology. In past and current collaborations with her partner, Lorenzo Triburgo, she created FLUID, Monumental Resistance: Stonewall, and Shimmer Shimmer – video, performance, and photographic projects that represent a call to action to fight for the issues she addresses in her research and life’s work.

Instagram: @alafemmegaze

Lorenzo Triburgo: I just want to start by saying thank you so much for initiating this. I always love the chance to continue our conversations.

Leni Mae Wiegand: Of course, it was great to see you at the Society of Photography Education conference in Reno, and since then, I have even had the opportunity to present your paper in GLQ “Representational Refusal and the Embodiment of Gender Abolition” to my MFA and BFA cohort at IU to a wonderful response.

LT: Awesome! Thank you! Having my work and ideas shared, taught and discussed as a form of education is a goal. There’s this wonderful statement etched onto the outside of the Museum del Barrio in Upper Manhattan that I take to heart, “A museum is a school: the Artist learns to communicate. The public learns to make connections.”

LW: Of course, starting from there as a jumping-off point, I have some questions about where you see your practice. As it’s really interesting, it’s in some parts photography, performance, and even a protest. Where do you see your practice living?

LT: My practice lives within the lens and its subversions alongside performance and installation as political and material explorations. I think the reason that I’m drawn to photography is for the fact of the lens. Perceptions of self, other, and society are individually created and constructed by dominant narrative both of which are manifested through the lens. This creates a productive space to undermine those narratives and passive beliefs

LW: How has that collaboration with VanDy shaped your work, and in what directions you take your projects?

LT: VanDy has their own individual research practice, and I have my own individual creative practice, but when we create together, it feels magical. Our relationship thrives in the collaborative space of creating art and shaping ideas together in writing. Working on projects like Monumental Resistance: Stonewall, FLUID (For Love Understood In Desire) and Shimmer Shimmer, where VanDy is behind the camera directing, has also allowed me to expand into performance and complicate notions of author and authenticity.

VanDy and I began our creative collaboration playing music together in the thriving queer music scene of Portland, OR in the early aughts, and our current project in process The Greatest Love integrates our background in music with video and installation. It is our most ambitious project to date.

© Lorenzo Triburgo and Sarah Van Dyck, Shimmer Shimmer installation view SPRING/BREAK Art Show, NYC 2022

LW: How did that project start and develop?

LT: I stopped taking testosterone specifically for Shimmer Shimmer, as a performative act towards the exploration of gender abolition. While we were making the images and sculptural pieces that would become Shimmer Shimmer, VanDy and I were also discussing how voice is another manifestation of gender perception. Notably, everyone was starting to wear masks at this time, so my voice (and gender) was being perceived without my face, and this of course also informed how people perceived VanDy.

VanDy started to give me voice lessons. In addition to her PhD in Industrial/Organizational Psychology with a research focus on disparities in healthcare and labor, and her background in stage management and set-building, she is also a classically trained singer who went to college on a singing scholarship. You can see why collaborating with her is so amazing! We started singing Whitney Houston’s The Greatest Love of All during COVID lockdown and it became a grounding practice.

When Iowa became the first state to revoke civil rights for trans* people in February this year (2025), we went to the state Capitol and sang The Greatest Love of All basically on repeat. This was an act of protest and an extension of solidarity towards our community; a reminder that “they can’t take away my (our) dignity.” People coming in and out stopped and talked with us and made videos. Some people sang along, and one woman stopped and just cried.

We plan on doing these guerilla-style performances at civic centers throughout Iowa and expanding into other Midwest states. We are in conversation with the amazing LGBTQ advocacy organization One Iowa and are seeking collaboration with other Midwest organizations doing the good work, fighting the fight.

LW: How has queer and trans community continued to play a role in your work? How do you feel things have changed since you made Transportraits and Policing Gender?

LT: I believe deeply in the power of community. The truth is, I don’t think anything can really happen without community. I don’t think a project comes to light without collaboration (named or unnamed).

VanDy and I both believe in “collaboration as a way of life” – and this undermines an oppressive, capitalist structure for art making and production.

In Monumental Resistance Stonewall we aimed to create a symbol of strength—to keep standing and keep fighting. My standing was an homage to the trans people of color who initiated the LGBTQ civil rights movement for us but have not received any ensuing rights or safety. Standing is also meant as a resistance to “resistance fatigue,” brought on the first Trump administration. I’m so disgusted even talking about this, because he and his administration have picked up where they left off and Project 2025 is horrifying and well underway. Monumental Resistance: Stonewall is unfortunately newly relevant because they just took the “T” off of the LGBTQ at the National Monument. So now if you go to the National Park Service for the Stonewall National Monument, it’s just an “LGB” monument — really just trying to erase trans* people from that history and from existence altogether.

Ironically, or perhaps predictably, I don’t think I would have made it all 24 hours without people coming over and giving me a hug, or giving me their dog to hold, taking selfies with me or cheering me on. Even the bar owners and people working that night would come and cheer me on, and that was kind of like an amazing revelation in terms of that exchange It was like, “oh, the community is really supporting me to accomplish this. This is such a beautiful flow of energy.”

LW: Just purely existing within that community space creates something that brings people together and gives back to the community. Where people were almost cheering you on, acting like they were on the fan cam at a sports ball game, giving you hugs, and pointing at the camera. It’s obvious how much it meant and the positivity it brought.

There is also that continued risk of being seen, even now, just like there was in 2008 with Transportraits, it’s a great deal of risk. Even with things like the so-called “Transgender Tipping Point” in 2014, we are living in a country and society that is getting increasingly vitriolic, like with the new Trump administration. But we then owe so much to those at Stonewall 50 years ago, where the violence they faced paled in comparison, and reading something like Stone Butch Blues where it’s one of the most terrifying things I’ve ever read it makes the erasure of early Black trans activists that much more despicable.

One thing that you wrote about that really resonated with me was your ideas around Representational Refusal and the option to not show oneself. It gave me the words to express how I was feeling as before that every discussion of my own work eventually lead to “well, how do you show that you’re trans? How else could we know without seeing your body? You have to show a picture of you!” and it just felt… draining and can we stop that, or should we stop? Because it simultaneously felt very important to be present and visible, but it also felt so draining as a constant element to think about.

LT: I appreciate your reference to the notion of “Representational Refusal” and the article VanDy and I wrote for the GLQ, “Representational Refusal and the Embodiment of Gender Abolition.”

When I decided to create Transportraits, before this supposed “tipping point,” it was based on the dearth of representation of transness, and transmasculinity specifically, in media, including fine art. But also, that the images that did exist were usually somber or sexualized. I wanted to create portraits that provided the satisfaction of adding to the increased representation of transmasculinities while also being critical of tropes in portraiture that feed exploitative image-making. It is important to note that the figures are all people who volunteered to be part of the project by word of mouth. They were courageous and gave me strength as well. The history of photography must be reckoned with if one is to engage with the medium. The consequences of being photographed have always been complicated and are increasingly so. The distribution channels are uncontrollable and the opportunity for harm is a reality.

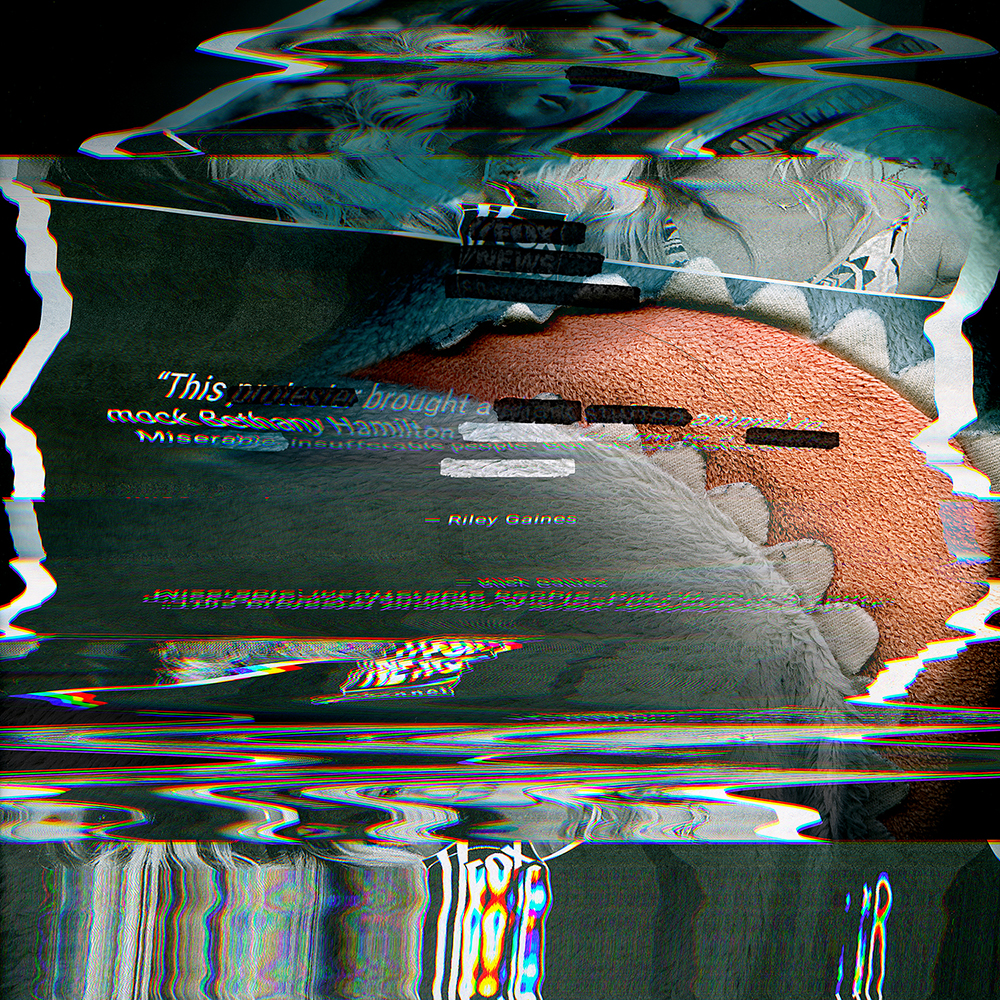

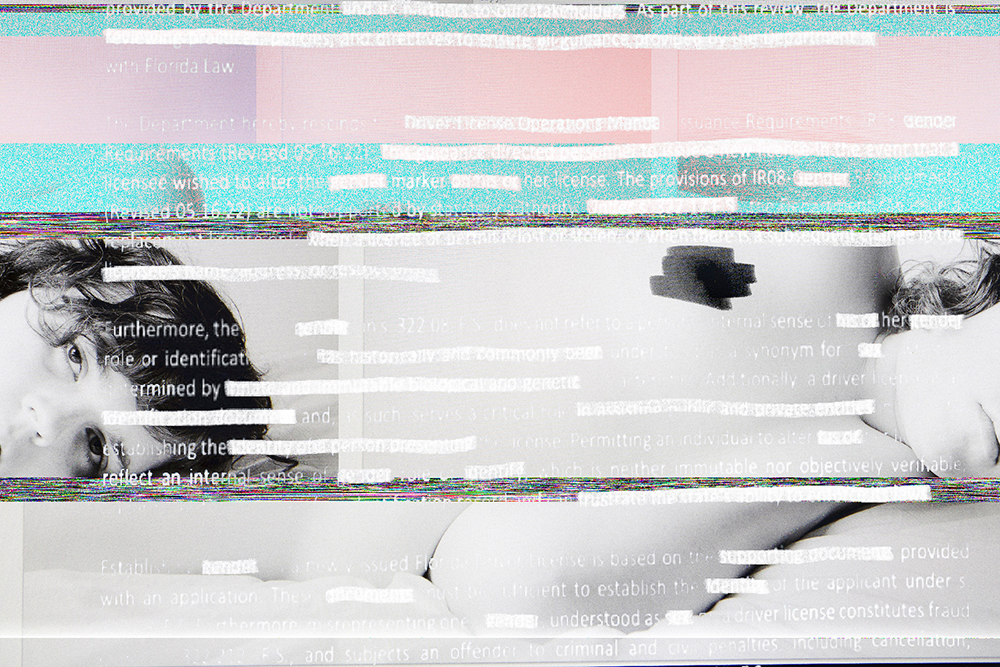

In the article we explain how my decision for Policing Gender to photograph fabrics as “figureless portraits” – draped as backdrops but without people in them – was a refusal to satisfy the seemingly insatiable appetite and commodification of trans* bodies and/or suffering at the time (2014-2015).

LW: Within a lot of your work, including Shimmer Shimmer, your projects are usually made up of various different pieces – like in Policing Gender, you have the absentee portraits, the audio, and the aerial photos. Where is your brain going in combining these different parts and approaches together?

LT: For each of my projects there are multiple layers of history, personal experience, politics, and the theoretical concerns that I believe will move us forward woven together. Research is a critical aspect of my practice, as is collaboration. For Policing Gender I wrote with my pen pals for over a year before making the images that would become the project. I worked with the prison abolition organization Black & Pink and did thorough research on prison abolition (that continues today). The prison industrial complex is complex and singular images could not hold that complexity. My discussion of this with Pete Brook, The LGBTQ Voices Propelling Prison Abolition: In Conversation with Lorenzo Triburgo was included in “A Syllabus on Transgender and Nonbinary Methods for Art and Art History,” by David J. Getsy and Che Gossett and I include a reading list at the bottom of that interview.

I included sound in Policing Gender because I wanted people to hear from my pen pals directly while keeping them anonymous for safety reasons. I also wanted the viewer to experience even a fraction of… the way that sound in these institutions is aggressive and violent. So, the viewer encounters these quiet, contemplative images of lush fabrics while also experiencing this disruptive sound, and then my pen pals’ voices.

The aerial images are taken from a hot air balloon and are about this idea of surveillance (and for any photo nerds reading this, the first reconnaissance images were created from a hot air balloon during the Civil War in the U.S.). The images are symbolic of “grand surveillance,” and reference, as we are currently witnessing, that as photographic technology evolves so does industrialized surveillance and our move closer to a fully realized military state.

The interesting thing is that the aerial images have been written about as being photographed around prisons, and they’re not. I think it’s a real testament to the fact that someone sees a 35mm format, black and white image, and they go, “oh, that’s… real. There’s got to be some sort of documentation happening here.” That dichotomy between the fabrics and the 35mm is very intentional. I am subverting the visual language of photography. I’m thinking about Queer(ing) Photography. My hope is, and this goes for all of my work, that part of “representational refusal” is also including hints or clues to queer people– that queer people will recognize but others may not.

LW: Almost like flagging, but within the images versus on the body.

LT: Yeah. For sure. I love that. It’s about creating a specific space for viewers to make connections. This is a motivation in my direction towards mixed media installation — creating space, allowing for multisensory contemplation and connections.

LW: My brain is always stuck on the performance aspects of taking self-portraits, as even doing it alone, I’m performing for the camera itself, just as I would for a person.

LT: Absolutely, I get that. Shimmer Shimmer is grounded in performance, as I mentioned with the cessation of taking T as one aspect of the performance happening on and off camera. One interesting note is that Shimmer Shimmer gets assumed to be self-portraits (kind of like the aerial images get assumed to be photographed at prison sites) but very much are not. This relates to what I said earlier about complicating notions of authorship.

SoMad Gallery created a 30 minute documentary about our process, shot while we made an image at Riis Beach and completed an installation at Spring Break Art Show, NYC. It shows our collaboration in real time – VanDy and I are setting up the shots together and conceptually designing them together. VanDy is directing me from behind the camera and the one ultimately “taking” the pictures. You see us create glitter constellation images that become floor-to-ceiling wallpaper and VanDy construct a glittery, grotto-inspired enclosure that we surrounded with sand from Riis Beach.

Each element relates to a history, a personal experience, and a politic. Riis Beach as our location, the process of body modification, performing for VanDy behind the camera in the dead of winter, and the materiality of glitter, each engage with the history of queer anti-assimilationist space, camp and queer joy, and the glittery resistance of trans* embodiment.

Lorenzo Triburgo and Sarah Van Dyck are Van Burgo Collective.

You can find their essay, “Representational Refusal and the Embodiment of Gender Abolition,” in a special issue of GLQ dedicated to abolitionist politics Queer Fire: Liberation and Abolition (Duke, 2022).

Their work Shimmer Shimmer is currently on view in “Glitter,” the first museum survey of glitter as a material at the Museum für Kunst & Gewerbe Hamburg, Germany (Feb 28 – Oct 10, 2025)

They can be reached at lorenzo@lorenzotriburgo.com, @lorenzotriburgo, and vanburgocollective@gmail.com

12 ©Sarah Van Dyck and Lorenzo Triburgo (Van Burgo Collective), At Iowa State Capitol, for their work-in-progress, The Greatest Love, 2025

Leni Mae Wiegand is a transfeminine lens-based artist. Her work focuses on data, glitch theory, and the importance of digital spaces for queer resistance.

She received her MFA in Photography from Indiana University in 2025, her BA in Business Management from Benedictine University in 2022, and their Associate’s Degree in Applied Science in Photography from the College of DuPage in 2020.

Currently shoved into her apartment’s closet are: 10 CRT TVs, 5 LCD TVs, 8 media players, and dozens of adapters that are utilized in her installations. This makes her mildly concerned that “Artist” is just another word for “hoarder.”

Instagram: @leni.film.photo

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026